A lthough cannabis has been used for various medical purposes over centuries,

1 it is currently not being officially prescribed due to law restrictions and lack of solid evidence regarding its objective clinical effects and safety. Nevertheless, there has recently been a growing interest about the potential therapeutic value of cannabis in several medical conditions.

1 –

4 Beneficial effects of cannabis in multiple sclerosis have focused much of the attention of scientists in the past few years.

2,

4 Illegal self-medication with cannabis both in smoked and in oral forms has, however, been reported for years.

5 Anecdotal reports suggest that cannabis can relieve not only muscle spasticity and pain but, in some cases, can also improve bladder control. Many randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials have attempted to investigate the potential efficacy of various cannabinoid treatments in managing spasticity, pain, bladder problems, sleep disturbances, and tremor due to multiple sclerosis.

4,

6 –

16 Results of clinical trials have been mixed, but together with insights from basic research and animal models of multiple sclerosis, they provide reasonable evidence for the potential therapeutic use of cannabinoids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis related symptoms.

1,

17 Findings of biological experiments have also revealed the possible immunomodulatory and neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids,

4,

18,

19 thus further supporting their potential utility in multiple sclerosis therapeutics. However, many issues still remain unresolved.

20 Accordingly, synthetic cannabis-based preparations [dronabinol (Marinol®), nabilone (Cesamet®), Δ

9 –tetrahydrocannabinol + cannabidiol (Sativex®)] have been used in the U.S., Canada and some other countries as an authorized treatment for nausea and vomiting in cancer chemotherapy, appetite loss in AIDS wasting syndromes and symptomatic relief of neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis.

3,

21 Recent research developments regarding the therapeutic use of cannabis analogues in several medical conditions and the concurrent possibility that cannabis might be fully legalized for patients with severe and chronic medical conditions such as multiple sclerosis provided the motive for this article. If cannabis products were to be used legally in the future for therapeutic purposes, this would naturally raise the concern of possible adverse effects associated with long-term use and especially with respect to the central nervous system (CNS) and cognition. It has been suggested that these effects may be greater in vulnerable groups such as patients suffering from diseases of the CNS. Non-acute cognitive dysfunction resulting from accumulative cannabis exposure has been a matter of investigation mainly with recreational cannabis users.

22 –

24 Psychiatric effects of long-term exposure to cannabis, such as comorbid depression and predisposal to psychosis, are issues that have also been reported in the literature.

25 –

27 Nevertheless, the focus of this article is the potential adverse effects of long-term exposure to cannabis-based medicinal extracts on cognition. The article provides a review of the current literature on this issue and critically considers the potential that cognitive deficits attributed to long-term heavy recreational exposure might be extended to controlled pharmaceutical use in multiple sclerosis patients.

Neurobiology and Pharmacology of Cannabis and the Endocannabinoid System

The main psychoactive component of cannabis is Δ

9 –tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ

9 –THC). The drug is most commonly delivered by smoking a plant-derived cigarette. Acute effects of cannabis have been well recognized, including euphoria and relaxation, intoxication, short-term memory impairment, disruption of psychomotor control, poor executive functions, distorted sense of time, increased appetite, and analgesia.

3 Acute panic, paranoia, and psychosis have been reported in some subjects.

26,

28 Although some researchers claim that marijuana is not particularly addictive, there is evidence that heavy and chronic users are likely to develop tolerance and dependence on the drug.

3,

29 –

30 On the basis of current research, cannabis does not appear to induce a clear withdrawal syndrome, as do other drugs of abuse, such as opiates.

31 However, there is no doubt that individuals suffer unpleasant effects when abstaining from chronic cannabis use.

31 Thus, although addictive behaviors such as compulsive drug seeking due to craving are rarely induced by marijuana use, preparations containing higher Δ

9 –THC concentrations, such as hashish, have been shown to induce addictive behaviors, especially in populations at risk.

32 Furthermore, some users develop problems related to the drug, and many request professional assistance in limiting their consumption.

33 Indeed, cannabis dependence is a DSM-IV diagnostic category. However, it has been proposed that dependence on cannabis should deal only with psychological dependence.

34 Whether a certain individual will eventually succumb to the addictive potential of cannabis will obviously be the outcome of a combination of factors. Thus, it has been suggested that the dependence syndrome on cannabis via international classification systems (e.g., DSM-IV) should be revised.

34Recent investigations have shed light on the mechanisms of the pharmacological actions of Δ

9 –THC and other chemically related molecules known as cannabinoids. Exogenous cannabinoids include phytocannabinoids such as Δ

9 –THC, cannabinol, cannabidiol, and other cannabinoid compounds present in extracts of the plant

Cannabis sativa, as well as synthetic cannabinoids produced in the laboratory. Two endogenous cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) have been identified

35,

36 although additional cannabinoid receptors may exist but have not yet been cloned.

37 Furthermore, endogenous ligands for these receptors have been isolated. These endogenous cannabinoids comprise a series of arachidonic acid derivatives such as anandamide, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), 2-arachidonoylglycerol ether, virodhamine and

N -arachidonoyldopamine which are referred to as “endocannabinoids” (for a review, see Mechoulam et al.).

38 Δ

9 –THC and other synthetic analogues exert their effects by acting as agonists at the cannabinoids (CB1 and CB2) receptors. However, some of the other constituents of cannabis, such as cannabidiol, which have well-documented biological effects of potential therapeutic interest, such as antianxiety and anticonvulsive properties, do not significantly interact with CB1 or CB2 receptors. This fact possibly explains the reason why cannabidiol does not possess psychotropic actions. Its effects have been largely attributed to inhibition of anandamide degradation or its antioxidant properties.

39 CB1 receptors are thoroughly expressed in the CNS, most densely in the frontal cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, hypothalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, and hippocampus, and are localized to axons and nerve terminals while being absent from the neuronal soma and dendrites.

3 In consistency with their presynaptic localization, the activation of CB1 receptors is thought to modify synaptic function by inhibiting the release of various neurotransmitters (L-glutamate, GABA, dopamine, 5-HT, and acetylcholine).

40 CB2 receptors, in contrast, are mostly found in peripheral tissues, predominantly in the immune system.

3 Interestingly, very recent evidence suggests that the CB2 receptors are expressed in the mammalian brain and may influence behavior.

41 The endocannabinoid system controls signaling processes between neurons in a retrograde manner. Endocannabinoids are not stored but are rapidly generated by postsynaptic neurons in response to Ca

2+ influx resulting from depolarization induced opening of voltage-controlled Ca

2+ channels.

42 When endocannabinoids are released from the postsynaptic membrane, they act backward across the synapse, tonically activating presynaptic CB1 receptors to decrease release of either inhibitory or excitatory transmitters.

40 Following an assumed cellular uptake mechanism, endocannabinoids are then degraded by intracellular enzymes. Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and a monoacylglycerol (MAG) lipase are the enzymes proposed to catalyze the hydrolysis of endocannabinoids.

4Endocannabinoids have been implicated in a variety of physiological functions. These areas of central activity include pain reduction, motor regulation, learning/memory, and emotion. Interestingly, recent evidence has emerged that tissue concentration of endocannabinoids and/or cannabinoid receptor density-activity changes (increasing or decreasing depending on the specific disease or pathological state) in a range of disorders.

43The Neuroprotective Role of Cannabinoids

Endocannabinoids might serve several functions in the brain. Of great interest is the potential neuroprotective role in the CNS. Experimental data indicate that endocannabinoids are released and accumulated in response to many different types of toxic insult, such as excitotoxicity, excitotoxic stress, traumatic injury and ischemia possibly representing a compensatory repair mechanism.

44 –

47 The excitotoxicity hypothesis is used to explain the common biochemical basis behind many acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders, including stroke, brain injury, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease.

48,

49 Thus, the cannabinoid system can serve to protect the brain against excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration and may play a primary role in limiting brain damage. Researchers’ current hypothesis of how cannabinoids provide their protective effects is perhaps that their general dampening of neural activity reduces excitotoxicity.

50 Cannabinergic activity through CB1 receptors is linked to signaling pathways that are protective against pathogenic insults and promote cell survival and maintenance. Such pathways include the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), such as the extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Activation of CB1 receptors has been shown to block presynaptic release of glutamate.

51 Interestingly, endocannabinoid levels were increased in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis,

52 although in a more recent study brain concentrations of endocannabinoids were not raised despite the cell damage induced by experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice.

53 The disruption of the neuroprotective effect of endocannabinoids was more pronounced in purinergic P2×7 receptor knockout mice after induction of EAE. The authors showed that in this mouse model of multiple sclerosis the limited production of endocannabinoids could be attributed to an interferon gamma-mediated disruption of the function of P2×7 receptors, the activation of which leads to increased production of endocannabinoids by microglia. Collectively, these results strengthen the concept that the endogenous cannabinoid system may serve to establish a defense system for the brain. This system may be functional in several neurodegenerative disorders as well as in acute neuronal damage.

Residual Neurocognitive Effects of Cannabis Use

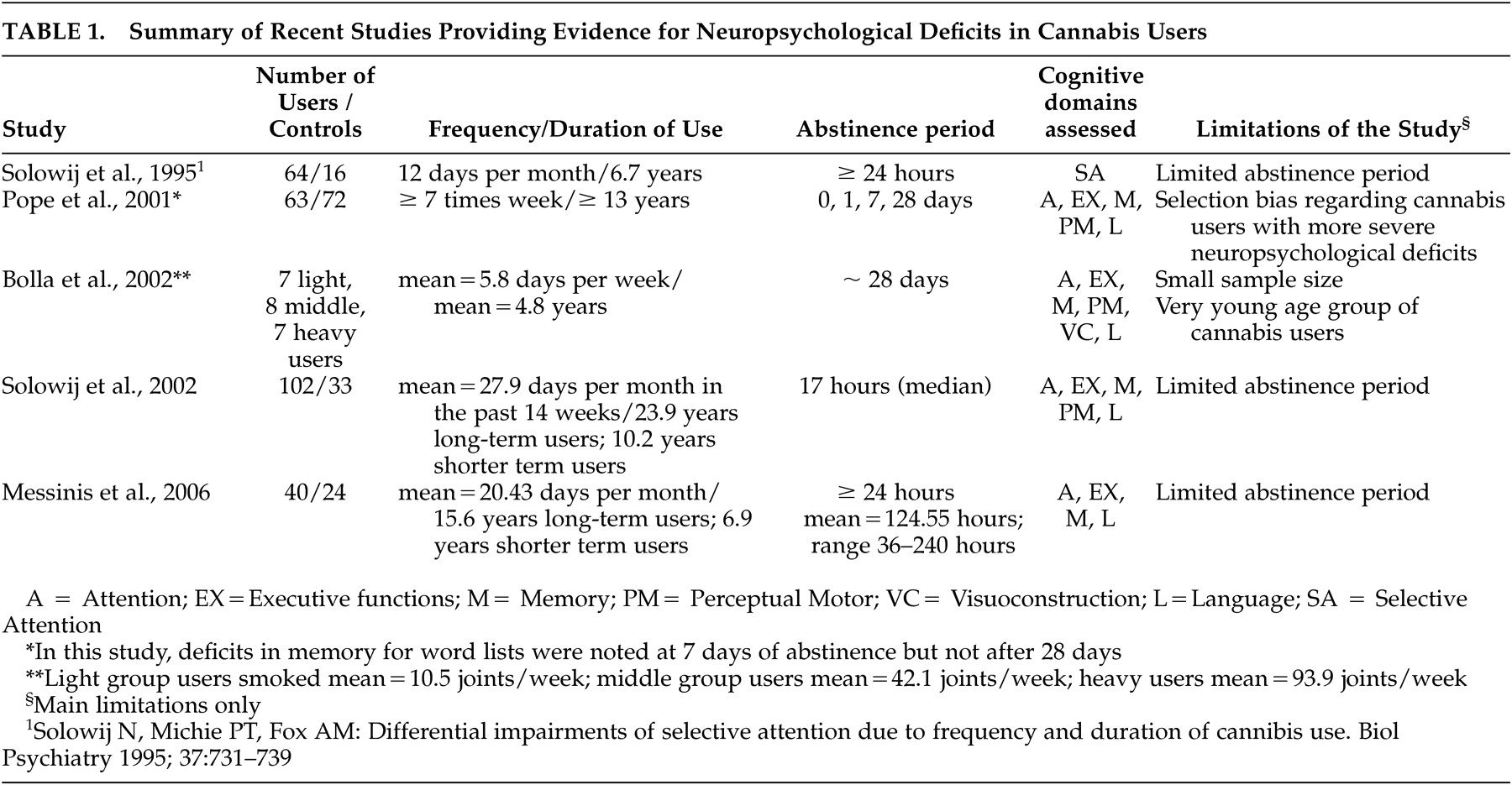

Although the acute effects of cannabis use have been well established, the question of whether chronic cannabis use causes residual neurocognitive deficits has produced conflicting data. Despite intensive research efforts in this regard, the literature remains divided and controversial, as no hard findings or consistent results have emerged. The cognitive deficits observed in chronic cannabis users may be temporary and reversible after a period of abstinence (attributable to late intoxication or withdrawal effects) or permanent (due to neurotoxicity). This question apart from its theoretical interest also harbors practical considerations regarding former drug user’s functional capacity after cessation of cannabis use. Even subtle cognitive impairments may prove a serious impediment especially for people whose occupation calls for intact agility and creative thinking. As far as current users are concerned, it is important to examine whether and how cognition is afflicted within unintoxicated intervals, in order to realistically assess functional operations in activities of daily living. Furthermore, it is essential to determine which variables of cannabis consumption (dosage, frequency, duration, or age at onset) independently correlate with cognitive deficits in cannabis users. The drug delivery is perhaps a critical parameter as well, since speculated neurotoxicity of cannabis may be dependent on the pharmacokinetic profile of the drug entering the organism. The smoked route is subject to wide variation.

54 Orally or sublingually delivered cannabis used in modern clinical trials may not provide standard dose absorption; however, the concentration curve of the drug is not as sharp as with smoked cannabis.

54 Intravenous administration retains control of dose but requires strict laboratory conditions.

54Evidence of cognitive impairment in chronic cannabis users is available in the literature, mainly concerning memory, attention, and executive functions, but it is not clear how long such impairments persist after cannabis use is terminated or whether these deficits are accompanied by drug-induced neuropathology. Studies of nonacute effects of cannabis on brain function require a period of abstinence to eliminate the acute pharmacological actions of the drug.

55 Another general issue affecting most studies on the nonacute effects of cannabis exposure is that the premorbid neurocognitive abilities of these participants are largely unknown; some of the cognitive deficits noted possibly reflect preexisting cognitive impairments rather than consequences of cannabis exposure.

22,

24,

55 Potential neurocognitive effects of cannabis withdrawal syndrome might also need to be considered.

29Pope et al. reported cognitive deficits in current heavy cannabis users after at least 7 days of abstinence. These, however, did not persist after 28 days of drug cessation and were related to recent, not cumulative, drug use.

55 On the contrary, Bolla et al. reported a dose-related effect of cannabis use on neurocognitive performance even after 28 days of abstinence.

56 Moreover, Solowij et al. have demonstrated cognitive impairments in long- versus short-term cannabis users after a median 17-hour abstinence period, indicating an important influence of duration of cannabis consumption on cognitive measures, predominantly verbal learning and memory.

57 In line with previous reports demonstrating cognitive impairment of long-term cannabis users in the unintoxicated state, Messinis et al. recently reported neuropsychological deficits in long-term heavy cannabis users after at least 24 hours (range=36 to 240) of abstinence, indicating duration, frequency, and possibly dosage of cannabis administration as determinants of this effect.

23 In the Messinis et al. study, verbal learning was the cognitive domain most substantially affected by chronic heavy cannabis use, followed by psychomotor speed, attention, and executive functioning.

23 Prior to this study, a meta-analysis of a small number of select studies on the long-term residual neurocognitive effects of cannabis use concluded that among various cognitive domains, impaired learning and retrieval of information were the only cognitive domains to demonstrate a significant effect size.

22,

24 See

Table 1 for a summary of recent studies evaluating the effects of cannabis use on neuropsychological functions. Therefore, deficits in verbal learning and memory tasks in long-term heavy cannabis users have variously been attributed to duration,

23,

57 frequency of cannabis use,

23,

55 or cumulative dosage effects.

56 The most pronounced evidence of impaired learning are effects on recall after interference or delay, flatter learning curves, fewer words recalled on each learning trial, and poorer recognition performance.

24The age of the cannabis users participating in neuropsychological studies also appears to influence their verbal learning abilities. More specifically, Fletcher et al. reported that only older (≥45 years) cannabis users differed from control subjects in list learning abilities, whereas users younger than 28 years remained unaffected.

58 Age at onset of cannabis use also seems to influence the occurrence of cognitive impairment, possibly attributable to a neurotoxic effect of cannabis on the developing brain.

59 Pope et al. recently reported that early onset of cannabis use (before the age of 17) is associated with poorer verbal IQ, even after adequate abstinence periods.

60 One important caveat in interpreting these results is that different behavioral trends of adolescents who use cannabis could account for these observations. In addition, visual search was found to be disturbed in early onset, long-term cannabis users.

61 The latency of auditory-evoked potentials has been reported to be significantly longer in cannabis users, especially in early onset users compared to healthy control subjects. In further investigating this issue, brain imaging studies report that adolescents who begin cannabis use before the age of 17 exhibit brain morphological changes, such as smaller brain volume, less cortical gray matter, increased cortical white matter, and increased cerebral blood flow, compared with late-onset users.

62 Increasing evidence further suggests that cannabis-based medicinal extracts may have toxic effects on the fetal nervous system.

19 Macleod et al.,

63 in a systematic review of the psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people, reported that available data do not support a causal relationship between cannabis use by young people and psychosocial harm, but cannot exclude the possibility of such a relationship existing.

There is laboratory evidence in support of neurotoxicity of THC. Results of both animal studies and in vitro cell experiments, however, have provided conflicting results.

3,

44 Chronic heavy cannabis use is not associated with structural changes within the brain as a whole or the hippocampus in particular,

64 so functional alterations might rather account for the observed neurocognitive effects.

Clinical neurophysiological studies have further contributed toward investigating this issue. Regular use of cannabis was associated with abnormalities in the P300 wave of event-related potentials during an auditory discrimination task

65 and electroencephalographic abnormalities in another study.

66Neuroimaging studies have also provided results indicative of persistent effects of cannabis on brain functions. Block et al.

67 and Matochik et al.

68 observed structural alterations in the brain tissue of frequent and heavy users, respectively, while Wilson et al.

62 reported brain morphological and functional changes in early onset cannabis users. Using positron emission tomography (PET), Block et al.

69 detected altered memory-related regional blood flow in the brain of frequent marijuana users after a minimum 26 hours of abstinence. Two other PET studies revealed altered patterns of brain activity in abstinent heavy cannabis users while performing tasks depending on executive functioning either in lack

70 or in presence

71 of performance differences. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study showed increased and more widespread brain activation in heavy cannabis users compared to controls while performing a spatial working memory task.

72 Two additional fMRI studies have demonstrated alterations in brain activity in heavy cannabis users during working memory assessments.

73,

74 Recently reported preliminary data from an fMRI study of verbal learning and memory in long-term cannabis users found altered activation of the frontal, medial, parietal, and cerebellar regions during the encoding and retrieval processes of words learned from the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

24,

75Cannabis users seem to exhibit compensatory shifts and recruitment of additional brain regions to meet the demands of various cognitive tasks. These findings could mean that long-term heavy cannabis consumption causes neurophysiological deficits, even in the case of minimally impaired or even normal superficial performance on neuropsychological tests. The subtle cannabis-induced changes in brain function may, therefore, have a huge impact on behavioral and cognitive measures in multiple sclerosis patients, in whom cognitive reserve is assumedly limited and compensatory mechanisms insufficient, as will be discussed below.

Cognition in Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is a multifocal demyelinating disease of the CNS, in which neuroinflammatory as well as degenerative processes are involved.

76 It is the most common cause of nontraumatic neurological disability in young adults and has a major negative impact on quality of life indices.

76 Cognitive impairment is considered one of the clinical markers of the disease.

77 Neuropsychological deficits of varying degree are present in almost 50% of multiple sclerosis patients, interfering with occupational and social functioning even in the absence of significant physical disability.

77,

78 Cognitive deficits in patients show no strong association to disease characteristics, such as disease duration, physical disability, disease subtype, or disease severity (lesion load in structural magnetic resonance imaging), with studies providing discrepant results.

77 No general consensus exists on the prevalence and special characteristics of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis, possibly reflecting disease heterogeneity and demyelination of different areas of the CNS. A review of the neuropsychological literature of multiple sclerosis using an effect size analysis, which gathered neuropsychological test results from a total of 1,845 multiple sclerosis patients and 1,265 healthy controls, confirmed that neurocognitive impairments are indeed evident in patients with multiple sclerosis on a number of cognitive measures.

79 This review also reported that chronic progressive multiple sclerosis patients display maximal deficits on frontal-executive tasks, whereas patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis present impairments predominantly on tasks of memory function.

79 Although the pattern of cognitive deficits identified in multiple sclerosis is not uniform, the domains most essentially affected are information processing speed and verbal memory.

77,

80,

81 A recent review of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis confirmed that measures of information processing speed appeared to be the most robust and sensitive markers of this impairment, and that single, predominantly speed-related cognitive measures may be superior to extensive and time-consuming test batteries in detecting cognitive decline.

82 Cognitive flexibility and executive functions, such as planning, have also been reported to be deficient.

77 A recent meta-analysis indicated that phonemic and semantic fluency, measures of executive functions, were among the most sensitive neuropsychological tests to detect cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis patients.

83 In a large series of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients, information processing speed was the cognitive domain most frequently impaired, followed by memory.

81 On neuropsychological testing of early phase relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients, information processing speed and memory task performances were impaired.

84 Deficits in the tasks of attention and information processing occurring early in the disease course have been attributed to working memory impairment and may, at least in part, account for subsequent decline in memory—mainly retrieval of information and conceptual reasoning.

85 Working memory deficits occurring early in multiple sclerosis were evident in two studies.

86,

87 Working memory is dependent on a network of functionally interconnected brain regions, which subtends rehearsal loops handling information load, that exceeds short-term memory storage capacity.

88,

89 Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis may result from an interruption of these loops, possibly due to white matter lesions. Compensatory mechanisms operate within the network of regions involved. Reserved brain regions may be recruited as a consequence of an adaptive response to neuronal dysfunction in one region in order to meet the demands of a cognitive task. Cognitive measures are not strongly and consistently correlated to structural damage (lesion load or brain atrophy) in conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

77,

90 More advanced MRI methods, such as magnetization transfer ratio or diffusion tensor imaging, capable of detecting subtle abnormalities in the normal-appearing white matter have been used, and the findings were shown to better correlate with cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis patients.

91,

92Explaining cognitive deficits in multiple sclerosis using multiple disconnections has recently focused interest. A dynamic assessment of brain activity during cognitive tasks has been attempted by three recently published fMRI studies. Two of these

93,

94 reported altered cerebral activation in multiple sclerosis patients performing equally well with controls in a sustained attention task and interpreted this as being indicative of compensatory and integrative mechanisms. On the other hand, one study

95 found no different pattern of brain activation in multiple sclerosis patients performing poorer than controls in a planning ability task, possibly reflecting exhaustion of compensatory mechanisms. Combined data of fMRI and structural equation modeling—representative of the change of activity of a target cortical area in response to a change in activity of a source area in a defined cognitive network—were used to assess effective connectivity inside the working memory network in patients at the earliest stage of multiple sclerosis.

96 Decreased effective connectivity between communicating components of this network was evident in this study and was attributed to regional fiber tract injury, as suggested by the authors. Higher activation and connectivity enhancement between some of the areas involved was also observed in patients and might be indicative of reorganization occurring in the CNS to compensate for diffuse white matter damage and limit its impact on working memory function. The neurochemical bases of such compensatory shifts in the impaired brain have not yet been established. Neuronal plasticity could account for this effect and might be triggered by a signal transmitted through the neural circuits of the implicated brain regions.

97A final issue that needs to be considered in this overview of cognition in multiple sclerosis is the potential influence of mood disorders, particularly depression, on cognitive dysfunction. Two recent reviews examining the neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis noted that nearly 50% of patients with multiple sclerosis will experience clinically significant depression in their lifetime.

95,

96 They further report that this figure is higher than in other neurologic disorders

95 and that it is approximately three times the prevalence rate of the general population.

95,

96 Recent reports further suggest that the core symptoms of depression may affect cognitive capacity by negatively influencing the executive component of working memory.

97,

98 Whether treatment of depression in this population may improve cognitive capacity, however, remains unresolved, as no direct studies examining this issue are available in the literature.

Neuropsychological Assessment in Clinical Trials of Cannabis-Based Medicinal Extracts (CBME)

Evidence from animal studies suggests that cannabinoids may inhibit muscle spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis and may also play a role beyond symptom amelioration in this disease. Such evidence has led to clinical trials for investigating the potential therapeutic efficacy of cannabinoid treatments in patients with multiple sclerosis. Although the evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis provided by these clinical trials is increasing, it is not as yet convincing.

13 –

15 The available clinical trial data suggest a beneficial effect on spasticity and pain based mainly on subjective measures.

14,

19 The data further suggest that the adverse side effects associated with cannabis-based medicinal extract use are generally mild and patients do not develop toxicity.

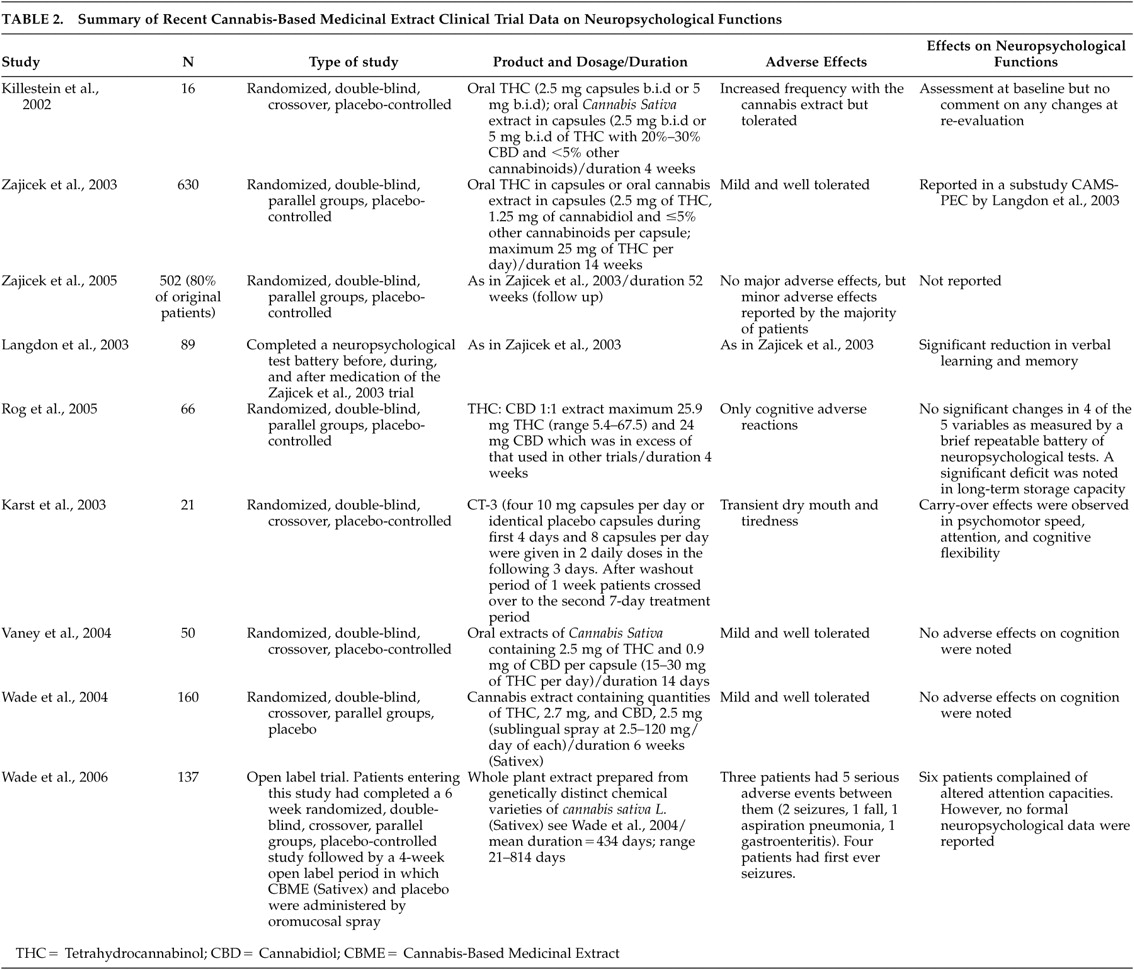

19The aim of this article, however, is not to discuss the effect of cannabinoids on various clinical measures of the disease reported in these trials. We specifically focus on parallel assessments of cognitive status of patients to discover whether any disruptive effects on cognition have been documented in these trials of cannabis-based medicinal extracts.

In 2001, 33 clinical centers in the United Kingdom and the United States undertook the study “Cannabinoids in Multiple Sclerosis (CAMS).” Its aims were to explore the effects of a cannabis extract, i.e., the combination of THC and cannabidiol (CBD) (Cannador®) or synthetic THC alone (dronabinol), versus placebo on spasticity, pain, tremor, bladder function, and cognitive function.

15 A total of 630 patients suffering from multiple sclerosis were treated for 15 weeks; 206 received the oral Δ

9 –THC in capsule form, 211 patients consumed an oral cannabis extract in capsules containing 2.5 mg of THC, 1.25 mg of cannabidiol and less than 5% other cannabinoids per capsule, and 213 patients took a placebo.

15 Medication dosage was based on body weight, with a maximum possible dose of 25 mg daily. The authors reported absence of beneficial effects on spasticity evaluated by the Asworth scale, but noted the limitations of this scale in measuring the highly complex symptoms of spasticity. An objective improvement in mobility was further noted with oral THC. The reported adverse effects were generally mild and well tolerated.

1,

15 In a 1-year follow up of this trial, in which 502 (80%) of the initial 630 patients took part, overall objective improvements of spasticity were observed mainly in patients taking Marinol®, although beneficial effects were reported by patients taking Cannador®. Overall, there were no major adverse effects, but minor adverse effects were reported by the majority of patients.

16The neuropsychological effects of cannabinoids were evaluated in a substudy (CAMS-PEC) of the main CAMS program. Eighty-nine patients completed a battery of neuropsychological tests before, during, and after the medication period. The battery was comprised of the California Verbal Learning Test, the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, the Digit Span, Digit Symbol, and the self-report Dysexecutive Questionnaire. The preliminary results of this substudy of the CAMS trial report a significant reduction in performance on the California Adult Verbal Learning Test (verbal learning and memory) in those receiving cannabis extracts compared with placebo.

102In 2002, Killestein et al.

8 were the first to publish the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effects of oral Δ

9 –THC and a

Cannabis sativa plant extract on multiple sclerosis (2.5 mg b.i.d. increased to 5 mg b.i.d.). In addition to various clinical assessments, the authors assessed the 16 patients who participated for possible changes in cognition with the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT), but did not comment on any alterations at reevaluation. Rog et al.

9 performed a randomized, controlled trial of a THC:CBD 1:1 extract in 66 multiple sclerosis patients suffering from neuropathic pain. The mean dose achieved of 25.9 mg THC (range=5.4 to 67.5) and 24 mg CBD is in excess of that used in other cannabinoid trials. The patients also underwent a brief repeatable battery of neuropsychological testing prior to first dosing and after 5 weeks at study completion or before in case of withdrawal. No significant changes were observed in four of the five neuropsychological outcomes measured. However, a significant difference in the long-term memory storage capacity assessed by the Selective Reminding Test was detected in favor of the placebo group as opposed to the active treatment one at the final evaluation. A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of the synthetic cannabinoid CT-3 on chronic neuropathic pain reported that CT-3 was effective in reducing chronic neuropathic pain compared with placebo, but noted carryover and period effects on the Trail-Making Test, a measure of psychomotor speed and attention.

103 Another randomized, double-blind, parallel groups, placebo-controlled study of 6 weeks duration examined the specific effects of Sativex® on symptoms in multiple sclerosis.

13 These authors detected significant reductions in spasticity and subjective improvements in sleep quality. In addition, participants were tested on cognition using the Adult Memory and Information Processing Battery Test of Attention adapted for patients with multiple sclerosis. No significant adverse effects on cognition were noted. In a recent long-term follow-up (mean = 434 days; range=21–814 days) of the Wade et al.

13 study, six multiple sclerosis patients complained of altered attention capacities. However, no formal neuropsychological data were reported in the follow-up study.

14 Another randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled study using the PASAT and the Digit Span Test found no significant adverse effects on cognition.

12 More recently, a study

104 evaluating the safety and efficacy of low dose treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid nabilone (1 mg/day) on spasticity-related pain in patients with upper motor neuron syndrome (UMNS) assessed neuropsychological functioning in a subset of these patients

105 and reported no cognitive side effects in the domains of attention, psychomotor speed, and mental flexibility after 9 weeks of treatment. There are also reports

106 from other neurological entities, with low doses of Δ

9 –THC (max 10 mg/day) that had no short- or long-term effect on neuropsychological performance of 24 patients with Tourette’s syndrome (see

Table 2 for a summary of recent cannabis-based medicinal extracts clinical trial data on neuropsychological functions).

Potential for Cognitive Adverse Effects of Long-term Cannabinoid Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis

Cognitive deficits resulting from chronic heavy cannabis use reported in neuropsychological studies

23,

56,

57 may become more apparent in populations already demonstrating cognitive impairment such as multiple sclerosis patients. Interestingly, memory and information processing speed deficits appear to emerge in both cumulative cannabis consumption and multiple sclerosis. In support of this hypothesis are the observed alterations in brain activities, which accompany both multiple sclerosis patients and long-term cannabis users. As mentioned above, endocannabinoids are major regulators of synaptic transmission in the CNS and might serve the signaling between functionally connected brain regions. Thus, endocannabinoids could mediate altered cerebral activation under certain circumstances, such as highly demanding tasks or coexistence of brain pathology.

By interfering with the elements of the endocannabinoid system, exogenous cannabinoids may disrupt rather than imitate its regulatory functions. Serious concern arises from the evidence that long-term exposure to both natural and synthetic cannabinoid agonists causes down-regulation and desensitization of CB1 receptors in the brain and perhaps underlying tolerance mechanisms.

107 Tolerance might have an impact on the multiple effects resulting from activation of CB receptors. The therapeutic efficacy could therefore dissipate over time, while a state of dependence could develop. Tolerance of many of the behavioral consequences of cannabis or to several of its adverse effects also develops. Recordings of hippocampal neuronal activity suggest that the hippocampus may become tolerant to the effects of cannabinoids on memory.

108 Interestingly, in a study assessing the effects of long-term heavy cannabis use on information processing speed, a deficit appears in users when they are in the subacute state (prior to cannabis consumption) which is normalized in the acute phase. The authors note that these results may be attributed to a withdrawal effect, but may also be due to tolerance development after prolonged cannabis use.

109 This would mean that due to changes in the molecular substrates, chronic cannabis users actually have a latent specific cognitive dysfunction which is masked by their cannabis dosing. The concerns extend to the neuroprotective effects of cannabinoids as well. As a result of decreased expression of CB receptors, cannabinergic signals may also be down-regulated and repair responses could be disrupted. Long-term users would be highly dependent on their medication to preserve any protective effects and perhaps an increase in the dose would be required to achieve the same level of neuroprotection or symptom relief. The patients might be vulnerable to the very insult the treatment was intended for.

The endocannabinoid system has been shown to mediate synaptic plasticity in an increasing number of brain structures and synapses. Δ

9 –THC and the cannabinoid receptor agonists have been shown to impair long term potentiation in the hippocampus, a proposed mechanism for memory and learning.

3 Chronic exposure to cannabis might cause permanent neurophysiological deficits that could influence endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS.

110,

111 Chronic THC exposure impairs endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in mice; however, compensatory mechanisms may be employed to rescue plasticity expression.

112 Such neurophysiological deficits possibly account for the residual effects of cannabis on cognition reported by neuropsychological studies.

As was shown in rats, cannabinoids may disrupt hippocampal neural encoding for short-term memory

113 and prevent the formation of new synapses between hippocampal neurons independent of the direct effects on neurotransmitter release.

114 Loss of synaptic efficacy induced by chronic cannabis consumption could result in an early breakdown of adaptive mechanisms in the context of preexisting brain pathology. Thus, influence of white matter lesions on cognitive functions in multiple sclerosis—otherwise initially restricted by remodeling of neuronal circuits—could be more pronounced in patients exhibiting blockade of neural plasticity due to long-term cannabis use. In accordance with this assumption lies the observed localization of CB1 receptors in the brain, which is denser in the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum. These brain areas are critically implicated in the neurocognitive functions most negatively affected by cannabis use. They have also been reported to participate in alternative brain activation patterns during complex memory and information processing tasks, even in the absence of disturbed neuropsychological performance. A selective deficit in learning and memory performance is observed in rat EAE, a popular animal model to mimic human multiple sclerosis.

115 Neuroprotective effects of CB1 receptor agonism have been reported in EAE,

2,

4 but to our knowledge, possible deterioration of cognitive status in EAE after prolonged treatment with cannabis has not yet been investigated.

To test a possible synergistic effect hypothesis between multiple sclerosis and cannabis use in disrupting cognitive functions, longitudinal, high-population, prospective follow-up studies would be required. Retrospective studies are easier to conduct, but controlling for confounding factors may not be satisfactorily achieved. It is critical to control for baseline neuropsychological performance both in respect to disease onset and to initiation of cannabinoid treatment, as well as the potential for concurrent situations or factors that may affect cognitive functions, such as use of other drugs, premorbid intelligence (crystallized intelligence), and presence of other neurological or psychiatric disease. In any case, it would be difficult to be certain to which degree cognitive decline observed at the time of reassessment could be attributable to cannabinoid treatment in medicated patients. Disease characteristics should be distributed as equally as possible between medicated and unmedicated patients.

HIV-infected individuals, prematurely demonstrating cognitive disturbances,

116 have similarly been shown to exhibit abnormal brain activation on fMRI preceding clinical expression of cognitive deficits.

117 A synergistic effect of HIV infection and chronic marijuana use on cognitive function was recently reported, although limited to advanced HIV cases.

118Symptomatic Treatment and Comparison of Cannabinoid Treatments in Multiple Sclerosis

Despite an advance on the treatment of multiple sclerosis in recent years, no treatment exists which definitely stops its evolution and numerous ongoing studies are searching for new therapeutic options.

119,

120 The traditional treatment for multiple sclerosis has been symptomatic, treating acute relapses without affecting the underlying disease. For the acute phase of the disease, there is generalized consensus on the use of corticoids; the most commonly used is intravenous methylprednisolone.

119 The introduction of interferon-beta (IFN-beta) has offered significant clinical benefits by reducing the frequency of relapses and slowing the disease progression.

121 Although interferon beta is considered the treatment of choice in preventing the evolution of remittent multiple sclerosis, there are questions as to which cases would benefit most, when it should be used, the type of interferon beta, the dose, and the route of administration. In this regard, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examining the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of every-other-day interferon beta-1b 250 ìg subcutaneous treatment in patients with a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis (clinically isolated syndrome) reported that interferon beta-1b delayed conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis, and that it should be considered as a therapeutic option in patients presenting with a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis.

122 A possible alternative to interferon beta may be the use of copolimere-1 or azathioprine.

119 Besides immunomodulation and immunosuppression, symptomatic treatment is an essential component of the overall management of multiple sclerosis.

120Symptomatic treatment in multiple sclerosis is aimed at reducing and eliminating those symptoms impairing the functional abilities and quality of life of the affected patients. Despite numerous therapeutic techniques and medications used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis symptoms, only a few have been investigated in multiple sclerosis patients and are approved by the respective national health authorities.

120 In addition, very few evidence-based studies exist despite the overwhelming number of publications.

119,

120 Recently, a consensus statement on the symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis was developed, comprising the existing evidence-based literature and therapeutic experience of neurologists who had dealt with such issues over a long time period.

120 In this consensus, statement proposals for the treatment of the most common multiple sclerosis symptoms, including disorders of motor function and coordination, cranial nerve function, autonomic, cognitive, and psychological functions, multiple sclerosis-related pain syndromes, and epileptic seizures, were presented.

120 Due to the fact that a more detailed description of the symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis is beyond the scope of this article, readers are referred to the Henze et al.

120 consensus statement for a comprehensive up-to-date report on this issue.

As stated previously, evidence from basic science and human trials suggests that cannabis-based medicinal extracts may have therapeutic potential in multiple sclerosis, particularly in the treatment of pain, spasm, spasticity and bladder dysfunction. Cannabis extracts contain a variety of chemical compounds and are likely to exert a multitude of effects, some of them undesirable or counteracting to the beneficial ones. The plant-derived cannabinoid preparation Sativex®, an oromucosal spray which delivers Δ

9 –THC and CBD in approximately equal concentrations, has already gained regulatory approval in Canada for the treatment of spasticity and pain associated with multiple sclerosis.

21 It has been postulated that the synergistic effect of both Δ

9 –THC and CBD will be more beneficial than a simple CB1 receptor agonistic action. Interestingly, patients with multiple sclerosis treated with Sativex® experienced improvements in the most disturbing symptoms, including spasticity, lower urinary tract symptoms, and neurogenic symptoms, without experiencing significant adverse effects in either cognition or mood and only mild intoxication.

6,

9,

12,

13,

123,

124 Δ

9 –THC acts on both CB1 and CB2 receptors and therefore lacks specificity. Selective CB1 agonists could therefore produce a selective therapeutic effect not observed with the use of medicinal extracts of cannabis. However, even selective activation of CB1 receptors can influence the release of more than one neurotransmitter in different brain areas. Synthetic agonists such as CP 55,940 and WIN 55,212–2 act as full agonists and could increase the potency of the effects produced by the activation of receptor. In this case, the adverse effects are not disengaged. As already mentioned, endocannabinoids are locally released at the site of neuronal damage in order to activate signaling pathways in the brain that are important for neuronal repair and cell maintenance. Such effects have been shown to result from cannabinoid receptor agonism. Thus, by enhancing the action of endocannabinoids we could promote endogenous repair signaling. Against this background, it remains to be seen whether novel molecules, optimized for modifying neural excitability and inflammation, may be useful in multiple sclerosis treatment. This strategy includes the administration of novel agents that can act as weak agonists at the CB1 receptor or agents that may not directly activate the CB receptors but might otherwise modify cannabinoid transport or metabolism. Specifically, weak/partial agonists at the CB receptors could have a therapeutic effect and also widen the therapeutic window since the current window between symptom relief and adverse effects of THC or direct cannabinoid agonists is narrow. Alternatively, modulating the availability of endocannabinoids by blocking the processes of their deactivation could locally target sites of damage where endocannabinoids are unregulated while sparing cognitive sites and reducing unwanted side effects.

2,

4 This latter approach includes therapeutic agents that inhibit endocannabinoid transport and degradation such as FAAH inhibitors, anandamide transport inhibitors and MAG lipase inhibitors. Boosting on-demand, region-specific brain endocannabinoid tone in treating multiple sclerosis is further supported in light of the recent report that the neuroprotective increase of endocannabinoids might actually be inhibited by a disease-associated cytokine. Interestingly, recent studies in a viral model of multiple sclerosis support this notion. Treatment of encephalomyelitis virus-infected mice with the anandamide transport inhibitors OMDM1 and OMDM2 enhanced anandamide levels, down-regulated inflammatory responses and ameliorated the motor symptoms associated with the demylenating disease.

125 Furthermore, recent data indicate that endogenously released cannabinoids and exogenously administered CB1 receptor agonists can differentially regulate synaptic inputs,

126 thus providing support of their discrete functional properties that may be of pharmacological interest.

DISCUSSION

In view of the prospect of chronically administering direct cannabinoid agonists not only as symptomatic treatment in advanced multiple sclerosis, but also as a neuroprotective agent in early multiple sclerosis patients, careful evaluation of neurocognitive effects of cannabis and disease-associated brain tissue damage should be undertaken. Hypothetically, a critical threshold has to be reached before cognitive impairment is clinically evident in multiple sclerosis. Cumulative lifetime cannabis use could synergistically further disrupt cognitive function in patients than the disease process alone. The assumed threshold for cognitive impairment to translate into clinically significant decline and influence functioning abilities or activities of daily living may be more easily reached in those patients who receive long-term high-dose cannabinoid treatment. This possibility, although not fully discouraging to the cannabis therapeutic application in multiple sclerosis, should at least pose limitations regarding dose and duration of therapy beyond individual acute intoxication effects. Dosage instructions may, however, be overlooked, as patients could develop dependence on the drug during therapy. Although the pharmacokinetic profiles of the orally or sublingually delivered versus smoked cannabis are different, the fear of abuse still exists.

Most clinical trials of cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis report generally mild and well-tolerated adverse side effects such as dry mouth, dizziness, somnolence, and acute intoxication. Nevertheless, more subjects in the active treatment groups than in the placebo group drop out of the follow-up studies due to adverse side effects. There is yet no direct evidence that multiple sclerosis patients might suffer a significant cognitive decline after prolonged administration of cannabis-based medicinal extracts. Available data indicate that this is not a serious problem at least in the short term. Because of the relatively short history of large-scale systematic clinical trials for cannabinoids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis, no definite information is provided on possible long-term cognitive adverse effects of cannabinoids. Cognitive deficits that have been attributed to long-term heavy recreational use are not necessarily extended to controlled pharmaceutical use. Such results, however, form the basis on which to raise this concern. Given the fact that multiple sclerosis patients differ from normal individuals in that they suffer from cognitive disturbances, this consideration certainly deserves further investigation. A more thorough and, in due course, repeated neuropsychological evaluation of the participants in the clinical studies is needed. Enhancing the responses of endogenous cannabinoids by inhibition of their deactivating processes may be the most preferable therapeutic strategy. Since such an effect would be limited at the site of damage and at the exact time of the endocannabinoid release, the therapeutic effect would be maximized and a disruption of cognitive networks elsewhere in the brain would be less likely to take place. The caution that we presently express involves not only acute psychotropic phenomena resulting from potent CB receptor activation, but more urgently the receptor down-regulation and impaired synaptic plasticity affecting cognitive systems after long-term administration of cannabis. In any case, safer and more valid conclusions will have to await the results of long-term, large-scale systematic clinical trials of cannabinoid-based medicinal extracts (CBMEs). Toward this end, a large-scale, multicenter trial is now underway in the United Kingdom, known as CUPID (cannabinoid use in progressive inflammatory brain disease), which will evaluate the effects of oral THC on 500 individuals with multiple sclerosis over a 3-year period.

20 It remains to be determined what type of cannabinoid agent and what route of administration are the most suitable to maximize the beneficial effects and minimize the incidence of undesirable side effects.

In conclusion, studies on cannabinoids and multiple sclerosis as well as on cannabinoids and cognition provide important new data, but all have their limitations with respect to the study design and interpretability of outcome. Furthermore, despite the enthusiasm about the reported clinical value of cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis, many issues remain unresolved in this area. Therefore, a balanced assessment of the risk-benefit ratio for cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis is still difficult to make. As long as the relevant evidence is not conclusive, clinical trials with cannabinoids that will provide more substantial clinical data, both about the efficacy of cannabinoids and about their long-term adverse side effects, are warranted.