D epression is the most common psychiatric disturbance found in individuals with Parkinson’s disease, with prevalence rates ranging from 20% to 50%.

1 Cognitive impairments also exist in a subgroup of Parkinson’s disease patients, especially on measures of memory, verbal fluency, and other executive functions.

2 Research suggests that the behavioral, motor, and cognitive impairments found in Parkinson’s disease patients reflect dysfunction of frontostriatal neural circuitry.

3 Additionally, cognitive and motor problems may contribute to the existence of depression in Parkinson’s disease,

4 and, conversely, symptoms of depression may impact cognitive and motor deficits.

5 Advances in neurosurgical techniques have made it possible to produce marked improvements in the motor impairments characteristic of medically refractory Parkinson’s disease.

6 Although deep brain stimulation has gradually replaced pallidotomy as the procedure of choice in North America and Europe, posteroventral pallidotomy is still widely performed in many parts of the world because it is effective, is much less costly, and does not require laborious programming. Unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy interrupts the neural circuitry believed to be responsible for the abnormally patterned motor activity in frontostriatal circuitry by lesioning the internal segment of the globus pallidus. After posteroventral pallidotomy, variable cognitive outcomes have been reported.

7 These variable results may partly reflect changes in motor functioning after surgery or surgical lesioning outside of motor tracts into more anterior or external portions of the globus pallidus.

8 However, one proposal that has not been explored to explain the variability in cognition after posteroventral pallidotomy is poor mood state.

Previous research indicates an association between impaired verbal memory and depressed mood in individuals diagnosed with major depression.

9 The relationship between depressed mood and memory impairment has also been demonstrated in patients who traditionally present in neurology clinics, including individuals with Alzheimer’s disease,

10 multiple sclerosis,

11 stroke,

12 and traumatic brain injury.

13 In individuals with Parkinson’s disease, the presence of depressed mood is related to poor encoding and retrieval of new information.

14 –

18 Surgical intervention for treatment of motor impairments provides a unique opportunity to test the premise that restoring more normal activity to the frontostriatal circuits will lead to improvements in mood state, which may in turn lead to improved cognition.

19,

20To date, no study has assessed the relationship between depressed mood and verbal recall ability after posteroventral pallidotomy. The goal of the present study was to evaluate poor mood state as a moderator of change in verbal recall ability from before to after posteroventral pallidotomy surgery using repeated-measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Motor disease severity was included as a covariate to control for the dual association that motor symptom severity has with both verbal memory and depressed mood.

21,

22 We also included side of surgery as a potential moderator variable given that previous research suggests that a different pattern of cognitive impairment exists based on the side of prominent motor symptoms.

23Participants

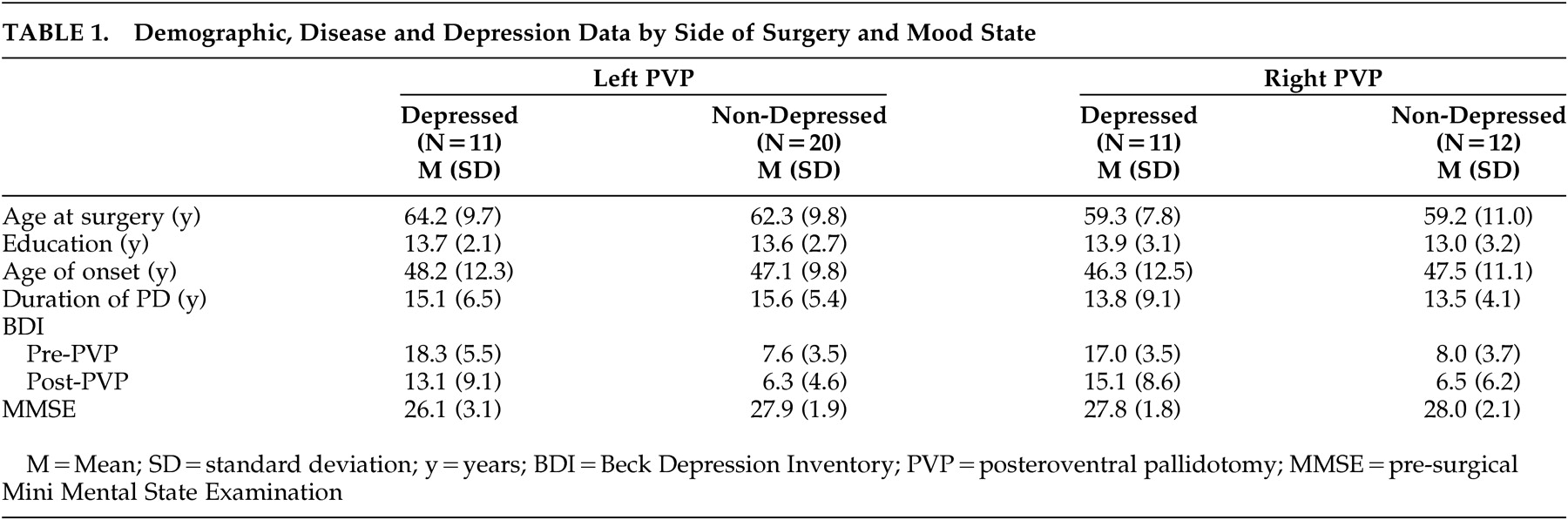

A retrospective analysis was performed on a series of patients who underwent unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy to relieve motor impairments associated with advanced, medically refractory Parkinson’s disease. Subjects were recruited from the Baylor College of Medicine Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic from 1995 to 2000. Fifty-four subjects (31 left-posteroventral pallidotomy, 23 right-posteroventral pallidotomy; 26 women, 28 men) were selected whose clinical findings were consistent with Parkinson’s disease (e.g., patients with dystonia excluded) and had both pre- and postsurgery memory and mood state data. Subjects who were included in the study because they had follow-up data did not differ significantly in chronological age, level of education, duration of illness or age at onset of disease, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor scores or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores compared to subjects who were excluded from the study. All 54 subjects had a history of response to

L -dopa therapy and all subjects had evidence of advanced disease based on disabling motor fluctuations,

L -dopa induced dyskinesias or freezing, and a Hoehn and Yahr Parkinson’s disease staging score of 3 or more during periods of medication withdrawal (“off” period).

24 No subject had a Hoehn and Yahr score of 5 during the “on” period. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the Institutional Review Board of the Baylor College of Medicine approved the research.

DISCUSSION

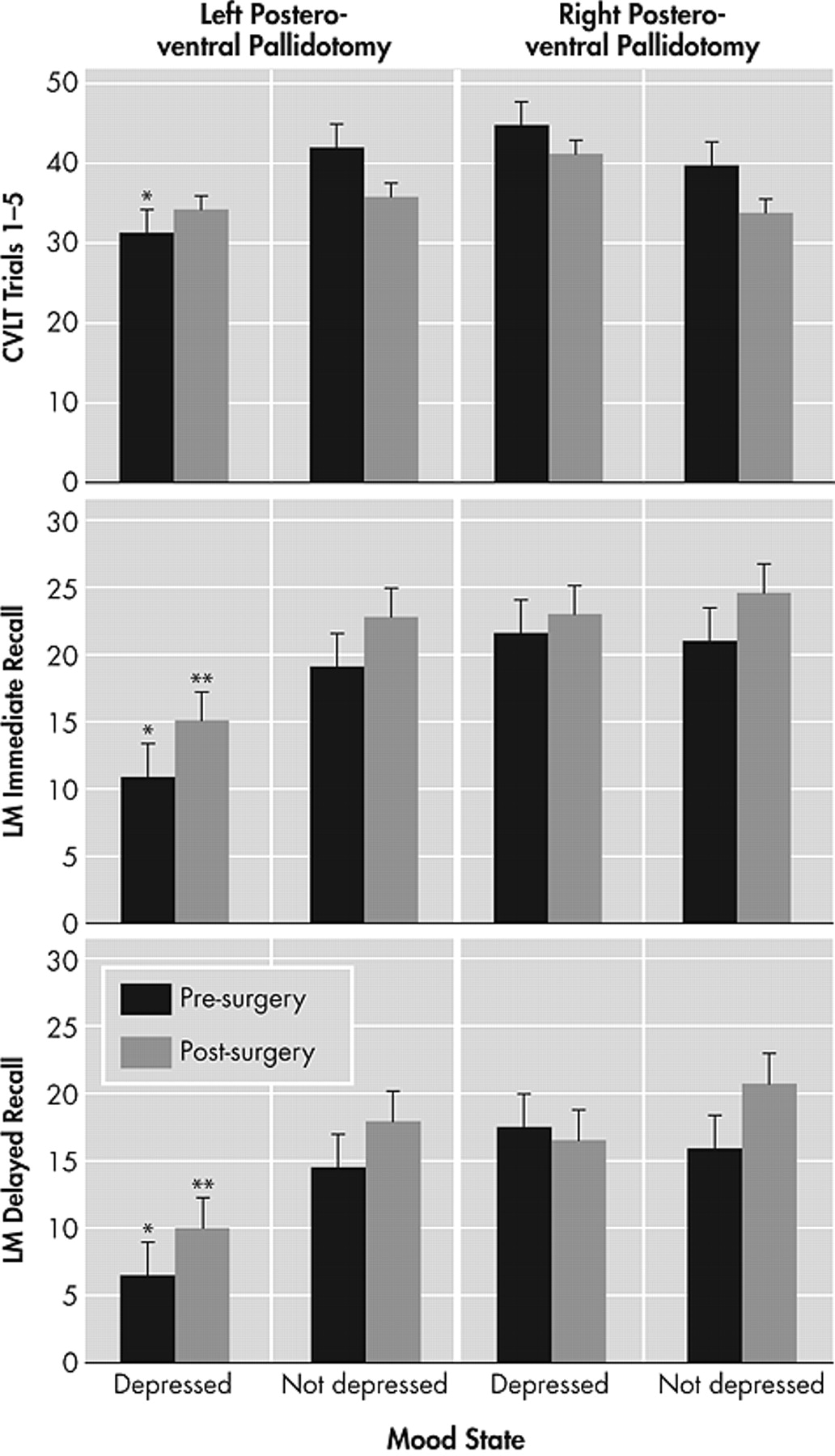

The present study examined the relationship between depressed mood and verbal recall ability from before to after posteroventral pallidotomy, controlling for motor disease severity. Results indicated that left-sided posteroventral pallidotomy surgical candidates with depressed mood performed poorer on measures of verbal memory, both before and after surgery, compared to left- or right-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects without depression and right-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depression. This pattern remained postoperatively. The presence of depressive symptoms in a subset of posteroventral pallidotomy patients may explain the variable results regarding the presence of cognitive impairment found in previous research. The findings are consistent with studies that have found a relationship between depression and verbal memory ability in nonsurgical medically managed Parkinson’s disease patients.

14 –

18 The results suggest that depressed mood should be taken into account when interpreting memory test performance in Parkinson’s disease surgical candidates both before and after surgery.

Similar to findings in individuals with left-sided epileptic seizure foci or left-sided stroke,

30,

31 we found that left-sided posteroventral pallidotomy surgical candidates with depressed mood had poorer verbal memory abilities compared to all subjects without depressed mood or right-sided surgery patients with depressed mood. The lateralized difference only found for left-posteroventral pallidotomy subjects may reflect the fact that verbal memory is a left hemisphere language-based function. It remains to be determined whether the results would differ if nonverbal memory measures were used. The fact that left-sided posteroventral pallidotomy subjects with depressed mood performed more poorly both before and after surgery suggests that interruption of abnormal globus pallidus output to the thalamus and cortex does not influence the significant relationship between depression and memory functioning. Given this, and the fact that the association between depression and memory continues to exist while controlling for motor symptom severity, the relationship may reflect a more permanent neurobiological phenomenon. Of note, memory impairment was relatively greater on the Logical Memory subtest (a 1–2 learning trial test) both before and after surgery compared to the California Verbal Learning Test (a 5-learning trial test). Though speculative, the performance of Parkinson’s disease patients on the list-learning task may indicate an improved ability to learn with repeated trials minimizing the planning impairments associated with frontostriatal dysfunction.

There are several explanations that might account for a relationship between depression and cognition in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. First, cognitive impairment may promote the presence of depressed mood. For example, the presence of memory problems may lead to restricted activities of daily living and reduced independence, which in turn lead to depressed mood. Second, depressed mood may increase the presence of cognitive impairments. For example, a patient with depressed mood may have greater difficulties directing attentional resources during effortful tasks compared to nondepressed individuals, or they may have covert verbalization of depressive thoughts and rumination that interfere with encoding of memories. The co-occurring behavioral and cognitive impairments likely reflect presurgical dysfunction of frontostriatal neural circuitry.

3 Research indicates reduced cerebral blood flow in areas important for both mood regulation and verbal memory in depressed individuals compared to nondepressed individuals.

32 A likely mechanism may be cortical cholinergic denervation, which is related to level of depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease patients with cognitive impairment.

33There is no agreement on the extent or type of lasting cognitive deficits that result after posteroventral pallidotomy. While some studies have not found any deficits in a variety of neuropsychological domains,

34,

35 some have reported lasting deficits past 6–12 months,

8,

36 and others have indicated that the cognitive changes are transient and return to baseline levels in 6–12 months.

37 One reason for the variability is that the extent of surgical lesioning outside of motor tracts into more anterior or external portions of the globus pallidus may lead to cognitive changes.

37,

38 However, the current findings also suggest that depressive symptomatology may account for some of the variability in findings. For example, pseudodementia, defined as a suppression of cognitive functions due to depression, may produce localized exacerbation of cognitive impairments leading to a misinterpretation of neuropsychological test scores.

39 Consequently, future studies should take clinically significant levels of depressed mood into account when interpreting short- and long-term postsurgical neuropsychological results, for example, with deep brain stimulation surgical candidates.

Results are consistent with other research that indicates an association between greater motor symptom severity and depression in individuals with Parkinson’s disease.

22 The relationship between depressed mood state and more severe motor disease is probably bidirectional such that motor problems may contribute to the existence of depression, and conversely classic symptoms of depression involve slower motor speed abilities. Results suggest that depressed mood is a predictor of poorer response to posteroventral pallidotomy given that subjects with depressed mood had more severe motor disease ratings after surgery compared to subjects without depressed mood.

One limitation of this study is its use of archival data, which potentially introduces selection bias. Thus, replication in a prospective cohort would strengthen extrapolation to other surgical Parkinson’s disease subjects. Future studies should also differentiate subtypes of mood disorders based on DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria. Further, measures such as the BDI are not optimal in patients with a chronic medical illness since some of the symptoms associated with a neurological illness overlap with depressive symptoms, which would inflate the BDI scores and lead to a greater likelihood of a depressed mood diagnosis. Future research should also determine whether depressed patients with left posteroventral pallidotomy have impairments in other cognitive domains compared to nondepressed patients. Future studies could also quantify type and dose of anticholinergic medications when evaluating the relationship between depressed mood and cognition. Finally, it is unclear how our results generalize to patients with new-onset Parkinson’s disease or less severe Parkinson’s disease, as well as to patients who are not good candidates for surgical intervention.

In conclusion, depressed mood was associated with poorer memory test performance. Results support the premise that the side of prominent motor symptom impairment and depression should be taken into account when interpreting neuropsychological test performance in surgical candidates with Parkinson’s disease. Further study of the relationship between depression and neuropsychological performance will improve the accuracy of our assessment of the strengths, weaknesses, and needs of the depressed patient with Parkinson’s disease, as well as lead to more effective interventions.