A pathy is a mental disorder characterized by lack of motivation. Marin

1 has defined apathy as a syndrome manifested by an absence of feeling or emotion, impaired cognitive function and reduced goal directed activity. Apathy occurs in a variety of neurological disorders including stroke,

2 Parkinson’s disease,

3 trauma

4 and Alzheimer’s disease.

5 Although the syndrome has not been defined by DSM-IV criteria, both Marin

1 and Starkstein

5 have suggested diagnostic criteria to define this condition. Abnormalities in aspects of emotion, cognition, motor function, and motivation have been suggested as the basis for the development of specific diagnostic criteria for apathy.

We have been studying apathy in patients with stroke since 1993.

2 The identification of apathy thus far has been based primarily on severity of scores on apathy rating scales.

2 We developed an apathy rating scale

2 based on a modified version of the scale proposed by Marin.

6 The Marin scale was modified to provide a more brief assessment. This modified version has been shown to be both reliable

7 and valid.

5 Using a cutoff score of 12 on our Apathy Scale, we found that 18 of 80 consecutive patients (22.5%) admitted to the hospital with an acute cerebrovascular lesion met this criterion for apathy. Of the 18 patients with apathy, half had associated major or minor depression. Poststroke apathy was also significantly associated with older age, cognitive impairment, and impairment in activities of daily living as well as lesions of the internal capsule.

2Although there is a strong association of apathy with depression, the distinction between depression and apathy is not difficult because of the symptoms in emotional, cognitive, psychomotor, and autonomic functions are very different between the two disorders (e.g., apathy is characterized by loss of emotion while depression is characterized by intense sadness of emotion.)

8 Furthermore, depression distresses patients while apathy distresses caregivers.

In spite of a growing interest in apathy, published treatment studies have been limited to anecdotal case reports generally utilizing dopamine agonists or stimulant medications.

9 –

12 Nefiracetam is a novel pyrrolidone-type nootropic agent which has been demonstrated in animal studies to enhance aminergic, glutaminergic, and cholinergic neurotransmission by stimulating α=4, β=2 type neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, activating protein kinase C, and reducing magnesium block of the NMDA receptor.

13 –

19 In addition, nefiracetam increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression as well as regional blood flow and glucose utilization after sustained cerebral ischemia in rats.

20,

21 This compound was first administered to humans in Japan as a potential treatment for poststroke cognitive impairment. Preliminary results published in Japanese language journals, however, showed an effect of treatment on outlook (i.e., optimism about the future) and interest (i.e., desire to undertake new activities), but no significant change in cognitive impairment.

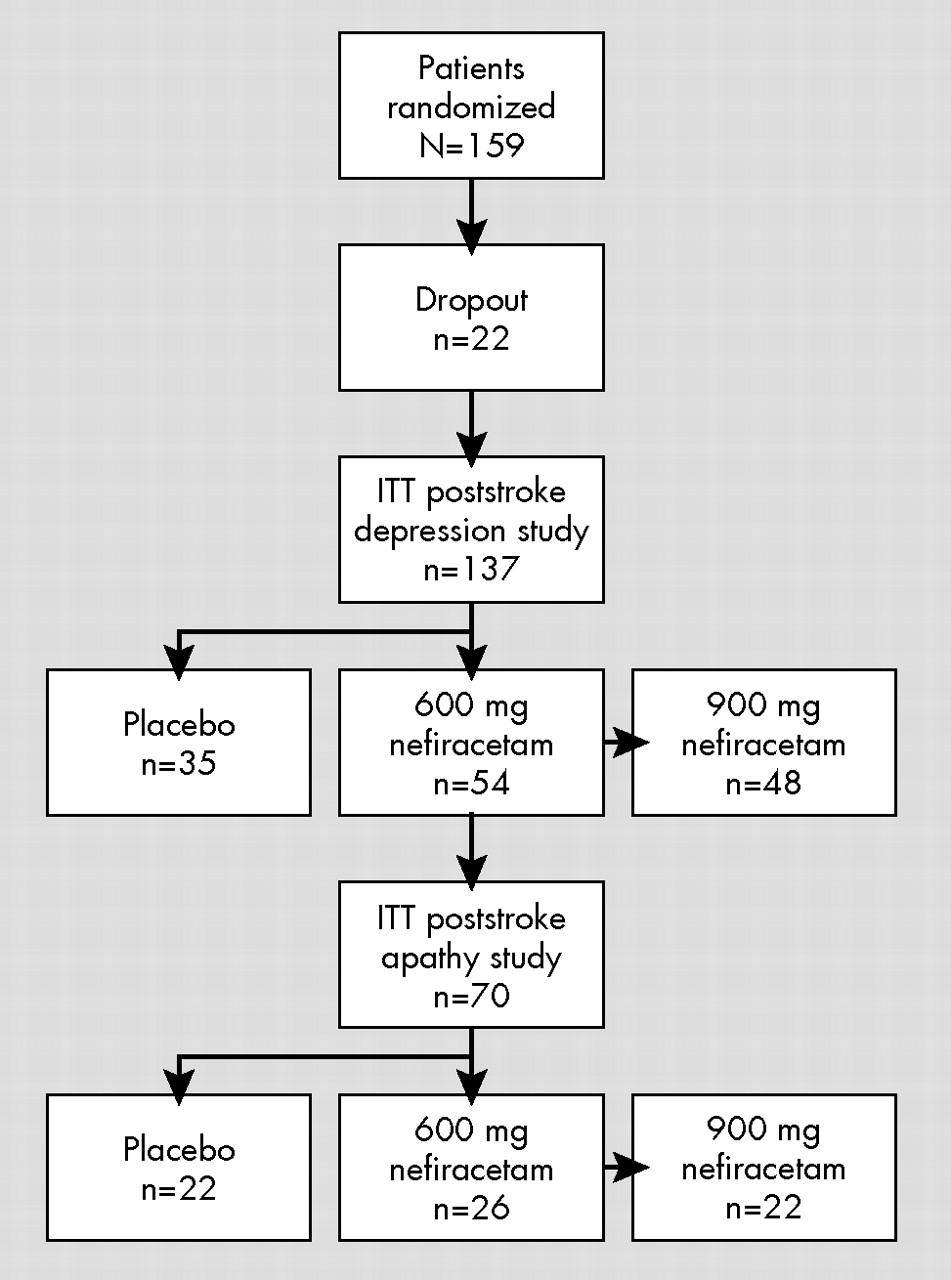

22The current study was therefore undertaken as part of a phase II trial of nefiracetam for treatment of poststroke depression

23 and, secondarily, apathy utilizing multisite enrollment and double-blind placebo-controlled methodology. This study thus represents a secondary analysis which was powered for assessment of depression, not for apathy. The hypothesis was that apathy, as well as depression would improve more following nefiracetam treatment, 900 mg/day, compared with placebo.

DISCUSSION

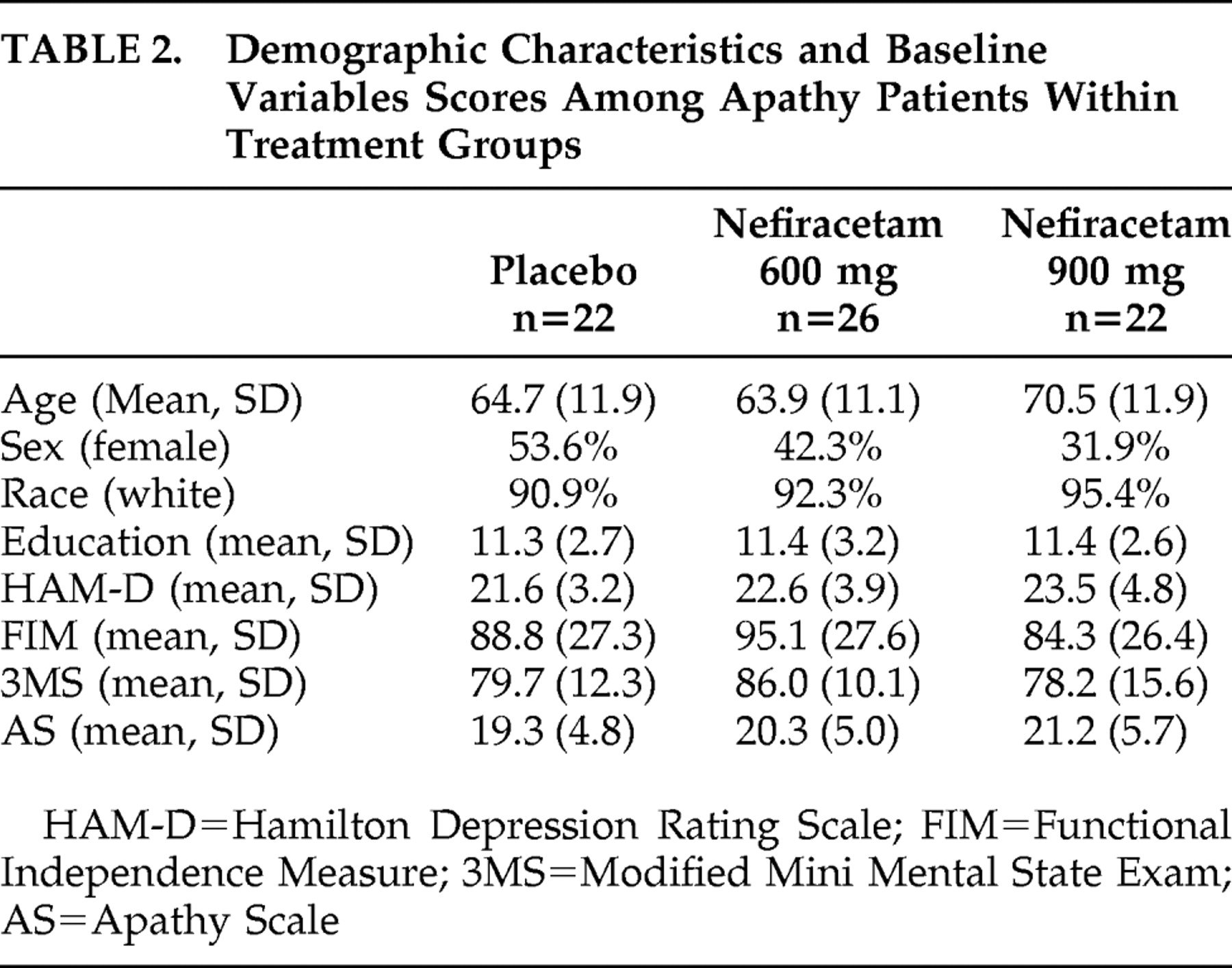

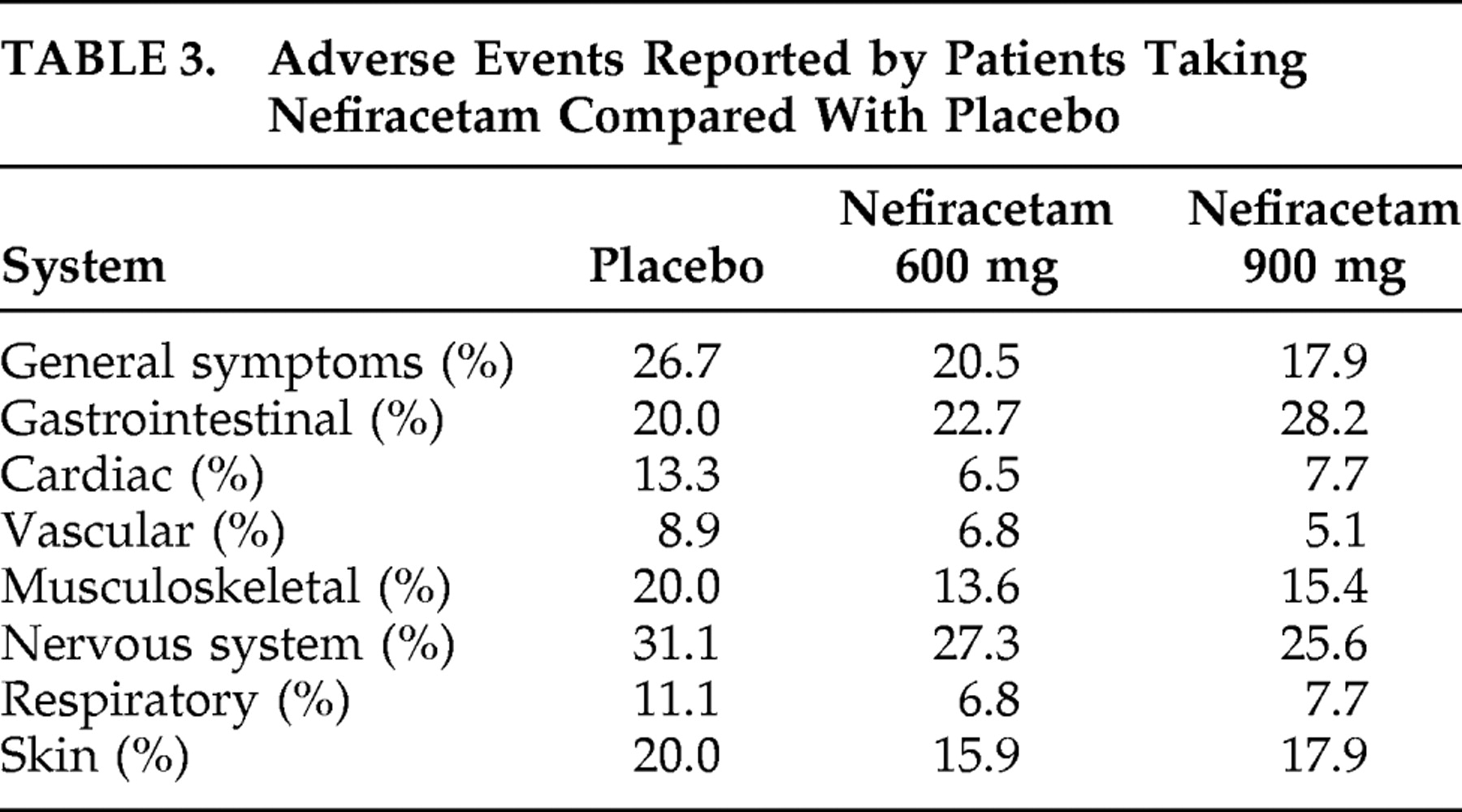

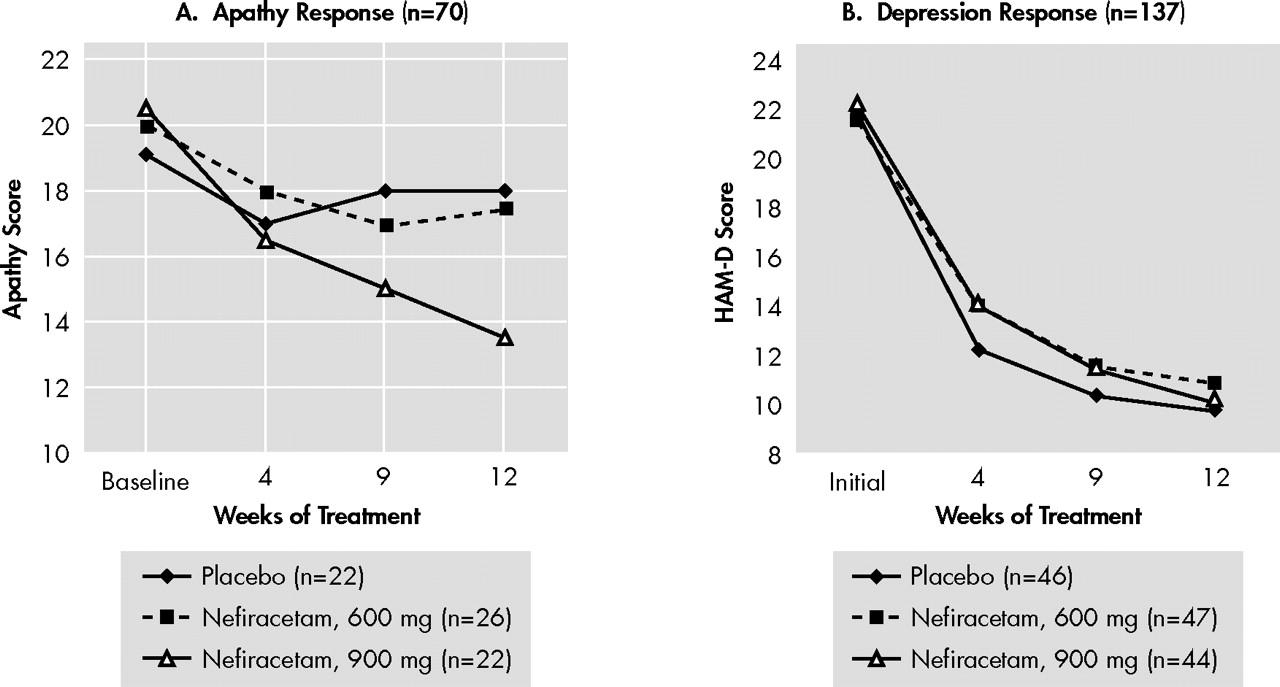

This randomized, double-blind study demonstrated that, among patients who met diagnostic criteria for both apathy and major depression, 900 mg of nefiracetam administered over 12 weeks of treatment significantly improved apathy scores compared with patients who received placebo or a lower dose (600 mg) of nefiracetam. On the other hand, 900 mg of nefiracetam was not different from placebo as a treatment for depression, suggesting that the differential effect of active versus placebo effect on apathy was different than the active versus placebo effect on depression. Finally, nefiracetam and placebo had few similar side effects.

This is the first trial, of which we are aware, that has demonstrated a significant treatment effect among patients with a diagnosis of apathy using double-blind, placebo controlled methodology. The first issue which must be addressed, however, is whether this response is simply due to an improvement in depressive symptoms. First, clinicians can readily distinguish between apathy and depression because depression involves feelings of sadness, sometimes with agitation, decreased sleep and appetite, hopelessness, self-blame, and suicidal thoughts. Apathy is characterized by lack of motivation and blunted emotional responses without the former symptoms. Second, the strongest argument for this being a specific effect on apathy is that active versus placebo treatment showed no difference on depressive symptoms, but a very significant differential effect on apathy symptoms. Thus, the treatment effect on apathy cannot be explained based on the treatment effect on depression.

There is a growing literature consisting of case reports and small series of patients who were treated for apathy with a variety of psychoactive agents.

4 Psychostimulants and dopaminergic agonists may modestly improve arousal and speed of information processing, reduce distractibility, and improve some aspects of motivation and executive function.

34,

35 However, the magnitude and temporal course of their therapeutic effect is still controversial.

36 Amantadine, a drug with pharmacologic effects on dopaminergic, cholinergic and NMDA receptors, could also have some efficacy in the treatment of motivational deficits.

37 –

39 Finally, there is some empirical evidence that cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil may improve motivation and general well being of patients with traumatic brain injury

40 –

42 and may improve apathetic symptoms among patients with dementia.

43 Thus, other drugs besides nefiracetam may be effective treatments for poststroke apathy.

Although the mechanism of apathy is unknown, Kalivas et al.

44 has postulated that the rostral cingulate, nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, and ventral tegmental areas constitute a core circuit in which motivational state is dependent upon the pattern of information in the core circuit. Limbic structures such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and frontal cortex modulate the core circuit based on the motivational and emotional significance of the internal and external input to these limbic structures. This hypothesis is consistent with the findings of Okada et al.,

45 using xenon inhalation methods, who found that 20 patients with apathy following stroke had significantly reduced regional cerebral blood flow in the right dorsal lateral frontal and left frontotemporal regions compared with 20 patients without apathy. In a more recent study of 29 patients with apathy and subcortical stroke, the same group of investigators reported a significantly prolonged latency and decreased amplitude of the P3-Novelty component of the auditory event-related potential in the frontal cortex.

46 It is plausible that hypoactivity in frontal and temporal lobe regions, and therefore reduced input to the core circuit, may be reversed by the enhanced aminergic, glutaminergic, and cholinergic neurotransmission produced by nefiracetam. Other mechanisms could, of course, be proposed.

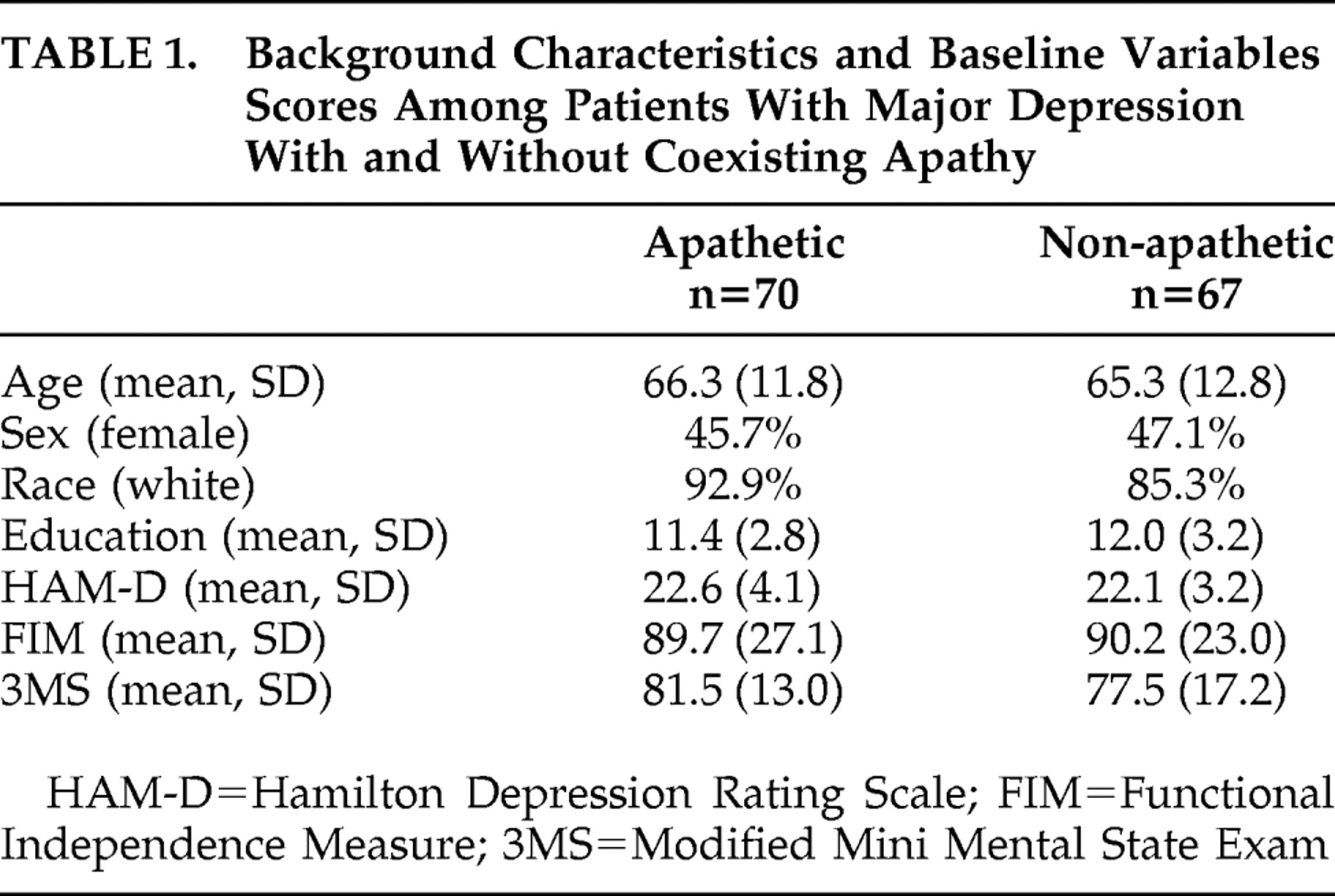

Finally, the limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, this was a secondary analysis and the study was primarily designed to assess response of poststroke depression to nefiracetam. Second, of the 159 patients randomized to the three treatment arms, 22 patients (13.8%) dropped out during the first month of the trial. Although there was a significantly lower frequency of apathy among dropouts than continued participants, there were no significant differences in demographic or baseline impairment variables between patients who remained in the study and those who dropped out. Although it is unlikely that this influenced our findings, attrition-related bias cannot be ruled out. Third, all patients enrolled in the study had major depression as well as apathy. Based on prior literature, about half of all stroke patients with clinically significant apathy would be expected to have depression.

2 We do not know, however, whether the response to nefiracetam was applicable only to patients with apathy plus depression or whether these findings apply to patients with apathy without associated depressive disorder. Fourth, we lacked sufficient power to examine whether apathy was associated with specific impairments such as cognitive function or specific lesion location. Finally, because this was a 12-week treatment trial without prolonged follow-up, we do not know whether the improvement in apathy symptoms continued after discontinuation of the drug.

In conclusion, apathy has received increasing attention because of its effect on emotion, behavior, and cognitive function. The current study is the first randomized double-blind treatment trial to be conducted among a large group of stroke patients with coexistent apathy and depression, and our results suggest that nefiracetam may be an effective treatment for this clinically important condition. Further studies in patients with apathy without associated depression are needed to determine the specificity of nefiracetam as treatment of apathy and whether treatment of apathy significantly improves long-term outcome and recovery.