Introduction

T ourette’s syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by multiple motor and phonic tics. Involuntary tic-related symptoms may include the uttering of offensive language (coprolalia), and comorbid psychiatric disorders including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are common. One study

1 found that many patients with Tourette’s syndrome experience urges to act in a socially inappropriate way (22%) or make socially inappropriate remarks including insults (30%). Failure to suppress these urges sometimes results in major social difficulties. These socially inappropriate behaviors may arise from inhibitory failure secondary to frontostriatal dysfunction. Moreover, patients with uncomplicated Tourette’s syndrome (i.e., motor and phonic tics only, with no associated behavioral problems) have been found to exhibit inhibitory deficits on the Hayling Sentence Completion Task—Adapted (HSCT).

2,

3 Such inhibitory deficits could lead to impairments in theory of mind.

Theory of mind describes the ability to understand people’s mental states (e.g., emotions, beliefs, intentions), which allows one to explain and predict people’s actions. Inhibitory dysfunction may impair theory of mind because appreciating another’s mental state necessitates inhibition of one’s own perspective. Developmental research has shown that early inhibitory control development predicts later false-belief understanding in children,

4 while one clinical case study showed right frontotemporal damage can lead to selective impairment on theory of mind tasks requiring the suppression of one’s own knowledge.

5 Inhibitory dysfunction in Tourette’s syndrome as indicated by deficits on executive tasks may contribute to theory of mind impairment, because brain regions active during these tasks are active when reasoning about others’ beliefs.

6Developmental researchers investigating theory of mind sometimes use the “unexpected transfer” task. During this task, a target moves from one location to another, while a story character is absent. Children exhibit understanding of the absent character’s false belief about the target’s location from around 4 years old.

4 Faux pas tasks are also used, which children pass between 9 and 11 years old.

7 These tasks feature a character making a remark that they are unaware is potentially offensive. Faux pas tasks may be harder to understand because they involve both the appreciation of the perpetrator’s false belief (the remark is inoffensive) and the victim’s emotional response (offense). Comprehension of the perpetrator’s belief about the victim’s mental state involves second-order theory of mind.

One study investigated theory of mind in uncomplicated Tourette’s syndrome.

8 No deficits were evident on two tests of higher-order mentalizing skills, though this could reflect small sample size or lack of sensitivity of the theory of mind measures. The present study investigated theory of mind in Tourette’s syndrome using a false-belief task

9 and a faux pas task.

7 Two executive tasks were used to assess inhibition (HSCT) and working memory (Digit Ordering Test—Adapted

10 ), which may affect task performance. We hypothesized that patients would exhibit deficits in theory of mind and inhibition but not in working memory.

RESULTS

Data analysis employed two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests and Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients.

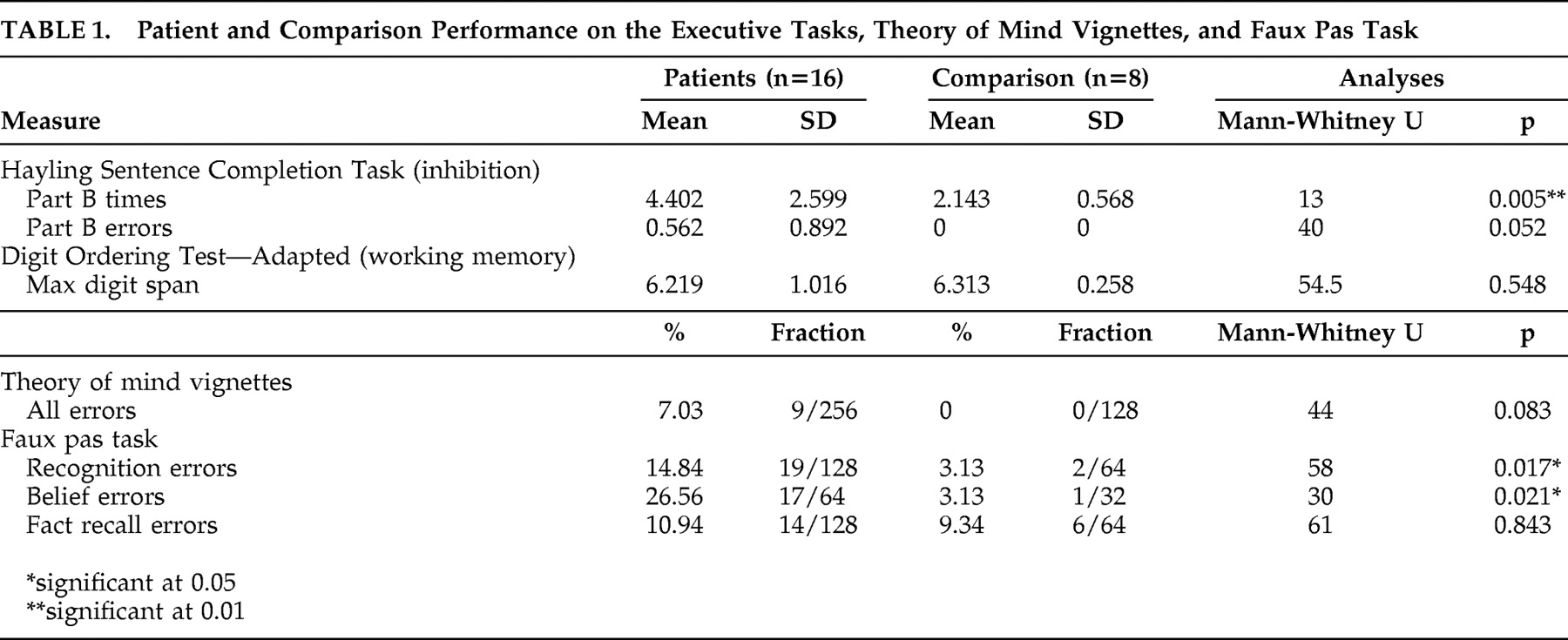

The results are shown in

Table 1 . Comparison subjects performed at ceiling on the Hayling Sentence Completion Task while six patients made errors, but this difference did not quite reach statistical significance. However, patients took significantly longer than comparison subjects to respond to inhibitory items, indicating possible inhibitory dysfunction. No significant difference was found between patients and comparison subjects on the Digit Ordering Test—Adapted.

The patient group made nine errors on the theory of mind vignettes, and though comparison subjects performed at ceiling, this difference was not statistically significant. Patients made errors on counterfactual, memory, and reality questions, providing no evidence for a specific deficit in false belief.

Patients were significantly poorer than comparison subjects at recognizing faux pas, but their recall of factual information contained in the vignettes was not significantly different.

More errors were made by patients than comparison subjects on faux pas belief questions, even on occasions when they identified faux pas. When failing to attribute a false belief to the perpetrator, patients often inferred the offensive remark was intentional. In such cases, explanations for the faux pas remark included anger, jealousy, or negative personality traits such as “nasty,” “mean,” “a bitch,” or “sarcastic.”

No significant correlations were evident for patients’ performance on executive and theory of mind measures.

Patients were grouped according to whether they reported obsessive-compulsive symptoms. These groups did not differ for performance on the Hayling Sentence Completion Task (times: Mann-Whitney U=8, p=0.079; errors: Mann-Whitney U=24.5, p=0.361), Digit Ordering Test—Adapted (Mann-Whitney U=31.5, p=0.0.957), theory of mind vignettes (Mann-Whitney U=20.5, p=0.138), or faux pas task (recognition: Mann-Whitney U=31.5, p=0.955; belief errors: Mann-Whitney U=19, p=0.148; fact recall: Mann-Whitney U=21, p=0.219). However, in relation to the nonsignificant findings it may be noted that sample size meant power value may be estimated at below 0.20.

DISCUSSION

Patients with Tourette’s syndrome made errors on theory of mind tasks despite unimpaired working memory and accurate recall of factual information contained in the vignettes. Theory of mind deficits were most apparent on faux pas tasks, where patients were specifically impaired on belief questions and inappropriately assumed the faux pas was intentional. This pattern of deficits was not associated with the presence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and did not correlate with inhibitory problems as shown by the Hayling Sentence Completion Task. The pattern, however, is similar to that seen in patients with frontal-variant frontotemporal dementia.

12Belief deficits on the faux pas task may have occurred because the task involves attributing intentions. Thus, patients’ difficulties may reflect not a deficit in theory of mind competence but rather a difference in application. Patients may be capable of understanding other beliefs but apply theory of mind reasoning differently in certain social situations. Developmental research shows that when belief and outcome information conflict, adults’ judgments are determined primarily by the belief while young children may fail to integrate beliefs and intentions and make judgments based on outcome alone.

13 Negative consequences therefore lead to negative attributions about an actor, regardless of whether the outcome was intended.

Frontostriatal dysfunction may reduce patients’ cognitive resources, leading to difficulties with the cognitively demanding task of reasoning about beliefs relative to reasoning based on consequences. Orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal activity has been linked to reasoning about others’ intentions.

14 These regions are also active when processing first- or third-person perspective and transgressions of social norms, along with the anterior cingulate gyrus, the temporal poles, and precuneus.

15 Activity in these regions may vary depending on whether transgressions are considered intentional or unintentional.

16 Changes in these brain regions could be associated with alterations in the attribution of intentions in Tourette’s syndrome.

Overall, these findings suggest that social difficulties may arise in Tourette’s syndrome from a lack of understanding of the intentionality of social actions. Although the small sample size may lead to caution about the generalizability of these findings as core characteristic features of Tourette’s syndrome, further investigation is clearly merited.