P arkinson’s disease is a debilitating and disfiguring disease associated with the presence of resting tremor, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Psychiatric disorders like anxiety and depression are common in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

1 –

3 Patients with disfiguring diseases experience significant distress in social interaction, and they may also develop social anxiety related to or secondary to Parkinson’s disease. Previous studies highlight the presence of social anxiety related to conditions like acne, psoriasis, hyperkinesias, obesity, and stuttering.

4 –

13 However, in DSM-IV, social anxiety related to a general medical condition like stuttering or trembling in Parkinson’s disease is excluded from the diagnosis of social anxiety disorder and these patients receive the diagnosis of “Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.”

14 Such a procedure has been criticized for limiting the diagnosis of this condition.

7,

11 Two studies reported high frequencies of social anxiety in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Stein et al.

15 reported in a small sample (N=16) that 29% of the patients had social anxiety. In the second study, the frequency of social phobia was 11.5% in a large sample of patients with Parkinson’s disease (N=384).

16 Primary or secondary nature of social anxiety was not assessed in these studies. In other words, these studies did not differentiate whether social anxiety was secondary/related to Parkinson’s disease or not. On the other hand, none of the patients with Parkinson’s disease had social anxiety in a comparative study investigating psychiatric morbidity in patients with cervical dystonia and Parkinson’s disease.

17 Since secondary social anxiety in patients with Parkinson’s disease had not been investigated in previous studies, our present study aimed to examine the frequency and severity of social anxiety related to Parkinson’s disease in these patients. The effects of age, gender, education, the severity of Parkinson’s disease, and psychiatric morbidities on social anxiety were also evaluated.

METHODS

The study sample consisted of the first 50 patients with Parkinson’s disease who were consecutively admitted to the Movement Disorders Unit of a university hospital during the years 2005 and 2006. The comparison group (n=50) consisted of age-, sex-, and education-matched volunteers without Parkinson’s disease who were the relatives of clinical staff. The study design was approved by the ethics committee of the university. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Neurological assessments of the patients were carried out by an experienced neurologist (MCA). Parkinson’s disease was diagnosed by United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Criteria.

18 The severity of parkinsonian symptoms was rated by the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS).

19,

20 In order to evaluate different manifestations of Parkinson’s disease, associated items were summed to obtain subscores. The subscore for bradykinesia is the sum of the scores of the items 23, 24, 25, 26, and 31; for tremor, the sum of items 21 and 22; for postural instability, the sum of items 28 and 30; and for rigidity, the score of item 22. The stage of Parkinson’s disease was determined by Hoehn-Yahr staging, and activities of daily living were assessed by the Schwab-England Activities of Daily Living Scale.

21 All patients were taking dopaminergic agents.

For the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, the Turkish version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I)

22 was administered. DSM-IV social anxiety A–G diagnostic criteria were used for the diagnosis of social anxiety, and the exclusion criterion (criterion H) of social anxiety related to a medical condition was disregarded. In other words, significant social anxiety, including social anxiety related to parkinsonian symptoms, which led to a decrement in social or occupational functioning and caused a certain amount of distress to the patient was considered as “social anxiety disorder.” In patients diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, the temporal relation between the social anxiety and Parkinson’s disease was also examined. The patients were asked about the onset of social anxiety symptoms and Parkinson’s disease as well as their attribution of social anxiety/avoidance to the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Therefore, social anxiety related to or secondary to Parkinson’s disease was differentiated.

Severity of social anxiety was measured by the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS). The LSAS is a 24-item scale consisting of items about social/interactional situations (13 items) and performance situations (11 items). Each item is rated for fear and avoidance on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more severe social anxiety and avoidance.

23 The LSAS is a scale which sensitively and specifically measures the severity of social anxiety and avoidance. Different cutoff scores yielded different sensitivity and specificity values in previous studies, however consistently higher values (sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 88%–100%) were obtained.

23 –

25 The Turkish version of the LSAS was validated by Soykan et al.,

26 and this scale was used in previous research investigating social anxiety secondary to physical diseases.

6,

10 –

12For the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (21-item version) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) were used. Higher scores indicate more severe depression or anxiety.

27,

28 Turkish versions of both scales have been validated.

29,

30Statistical Analysis

Between-group differences were tested by independent samples t test or Mann-Whitney U test, where appropriate. Linear relationships were analyzed by Spearman’s correlation test. The effects of age, severity of depression, and parkinsonian symptoms on the severity of social anxiety were tested by stepwise linear regression analysis. All statistics were carried out by SPSS 13.

RESULTS

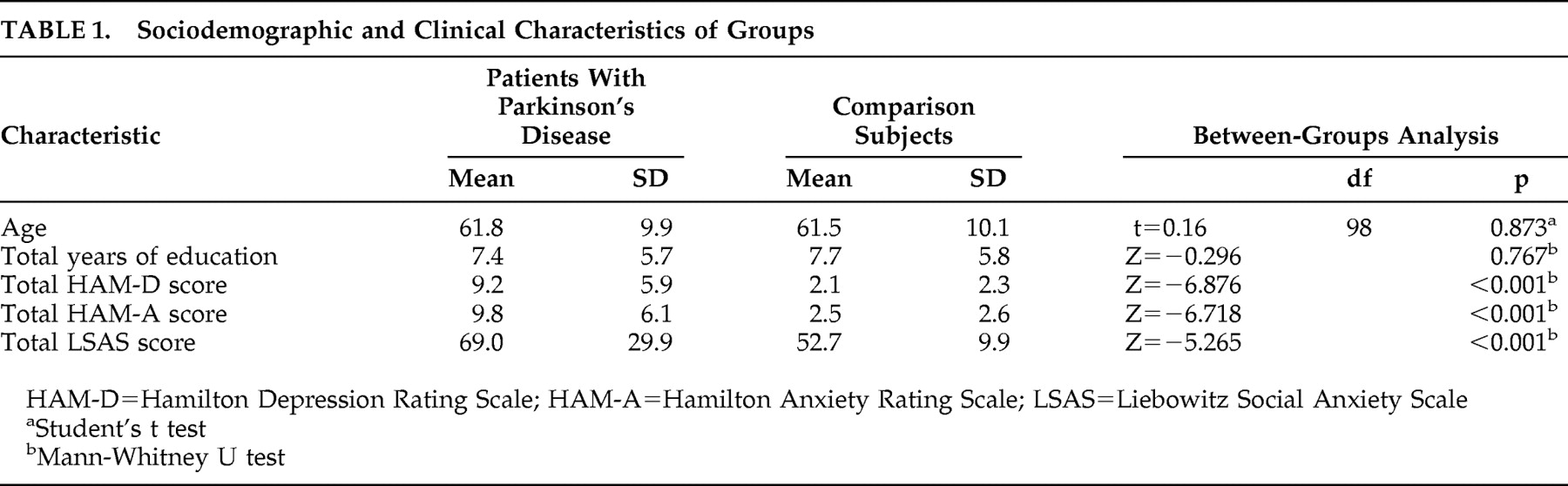

Both groups consisted of 30 male and 20 female participants. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of age and education. Total HAM-D, HAM-A, and LSAS scores were significantly higher in the patient group (

Table 1 ).

Social anxiety disorder was diagnosed in eight patients (16%) with Parkinson’s disease. These patients reported social anxiety related to Parkinson’s disease. None of these eight reported social anxiety disorder before the onset of Parkinson’s disease. Of the patients with Parkinson’s disease, 15 had a major depressive episode and two had comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. Two of the patients with secondary social anxiety also had a diagnosis of major depressive episode. In the comparison group, one patient had social anxiety disorder (2%) and one had a major depressive episode (2%).

Mean UPDRS subscale and total scores of the patients are given in

Table 2 . Forty-eight percent of patients (n=24) were at Hoehn-Yahr stage 2.5, 22% (n=11) were at stage 2, 22% (n=11) were at stage 3, 4% (n=2) were at stage 1, and 4% (n=2) were at stage 4.

Total LSAS scores were negatively correlated with age and positively correlated with total HAM-D patient scores (R=−0.283, p=0.046; R=0.548, p<0.001). Total LSAS scores of the patients were positively correlated with the total UPDRS scores, as well as the subscores of mentation, behavior and mood, activities of daily living, and bradykinesia (R=0.409, p=0.003; R=0.623, p<0.001; R=0.345, p=0.014; R=0.322, p=0.023, respectively). Schwab-England Activities of Daily Living Scale scores were negatively correlated with total LSAS scores (R=−0.306, p=0.03). There was no significant correlation between total LSAS scores and other subscale scores of UPDRS (p>0.05). Education was not correlated with total LSAS scores either. There was no significant difference between male and female patients in terms of total LSAS scores (p>0.05). Also, there was a positive correlation between total UPDRS scores and total HAM-D scores of the patients (R=0.583, p<0.001).

Stepwise linear regression revealed that HAM-D total scores (standardized β=0.411, p=0.001) and age (standardized β=−0.425, p=0.001) predicted the severity of social anxiety, and this model explained 59.5% of the variance, while the total UPDRS score was not in the equation.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous research, we found a high frequency of social anxiety in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Current literature on social anxiety related to medical conditions clearly demonstrates the importance of this condition, since the rates reported in the present study, as well as in previous studies, are considerably higher than the rates of primary social anxiety disorder in the general population.

31,

32In a comparison study, we reported high frequencies of secondary social anxiety in patients with hyperkinetic movement disorders like essential tremor (30%), cervical dystonia (30%), and hemifacial spasm (20%).

11In contrast with the classical notion that patients with Parkinson’s disease often avoid public situations so that their symptoms like tremor and dyskinesias will not be noticed,

33 the severity of social anxiety was not associated with the severity of Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Although there was positive correlation between UPDRS scores and LSAS patient scores, regression analysis revealed that only HAM-D scores and age were associated with LSAS scores. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that UPDRS patient scores were also positively correlated with HAM-D scores. In our previous study, the severity of social anxiety was not associated with the severity of the hyperkinesias either. In both of our studies severity was associated with younger age and depression.

11 Yolac Yarpuz et al.

12 also reported higher social anxiety and depression in patients with acne. Similarly, in acne patients social anxiety was negatively correlated with age, but it was not correlated with the severity of acne.

This study has some strengths and limitations. Social anxiety was investigated in a large sample of patients with Parkinson’s disease and compared with a matched comparison group. Moreover, this is the first study which specifically investigates social anxiety related to Parkinson’s disease. Since social anxiety was associated with depressive symptoms, the presence of depressive symptoms/major depressive disorder may have inflated the rate of secondary social anxiety disorder in this sample. On the other hand, our sample mainly consisted of patients with a mean age of 61 years old; therefore, the observed rate in the present study may be lower than the rate of social anxiety in patients with early-onset Parkinson’s disease (onset before the age of 40). In addition to that, most of the patients in this study had mild–moderate Parkinson’s disease, so the frequency of disease-related social anxiety might be lower than in severe forms of the disease. We did not examine the duration of Parkinson’s disease and disease-related disability which might affect the development of social anxiety. Although the duration of hyperkinesias or the disability level were not associated with the severity of social anxiety in our previous study,

11 both of these factors should be controlled in future studies. Furthermore, our comparison group consisted of healthy volunteers without any disabling medical illness; therefore, future studies may also compare social anxiety in Parkinson’s disease with social anxiety in other chronic medical illnesses.

Although clinical research on social anxiety in Parkinson’s disease patients is scarce, there is also neurobiological data which points out a common possible hypodopaminergic etiology in social anxiety and Parkinson’s disease. Striatal dopamine reuptake and D

2 receptor binding were lower in patients with social anxiety.

34 –

36 However, a recent study by Schneier et al.

37 found no difference between patients with generalized social anxiety (n=17) and healthy comparison subjects (n=13) in terms of striatal D

2 receptor or dopamine transporter availability. Generalizability of the findings in these studies is limited due to small sample sizes; therefore, future studies should investigate the possible biological link between the two diseases in larger samples.

Management of social anxiety and depressive coping style in these patients is necessary adjunct to the treatment of the primary disease since social anxiety is not associated with the objective severity of the disease. Therefore, neurologists dealing with these patients should be aware of social anxiety related to movement disorders and refer them to psychiatrists. Heinrichs et al.

38 reported a successful cognitive behavior therapy with a patient with Parkinson’s disease who also had social anxiety. However, there is no study investigating the treatment of social anxiety related to Parkinson’s disease or other medical conditions.

Since social anxiety in the context of a disability or disfigurement may present with symptoms similar in nature and severity to the social anxiety disorder defined in DSM-IV-TR, symptoms can be managed and treated the same way as in cases of “primary” social anxiety disorder. Revision of the criteria for social anxiety disorder in future diagnostic systems, such as DSM-V based on current evidence, is necessary. For example, exclusion of criterion H might be considered in the future DSM definition of the disorder. This would provide detection and management of these symptoms, as well as a basis for future research.