The estimated lifetime prevalence of mood disorders in the general population is approximately 10 to 15 percent (

1 ). From a population-health perspective, mood disorders are currently the leading cause of disability and premature death among young adults (

2 ).

A mounting scientific database documents the increased prevalence of medical comorbidity among persons with a mood disorder (

3 ). For example, subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with recurrent depression, longer disease duration, more frequent affective episodes, repetitive nonlethal suicidal behaviors, and a higher body mass index (

4 ).

Emerging clinical evidence also indicates that general medical disorders are highly prevalent among bipolar probands. For example, migraine headaches and cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, pulmonary, and infectious diseases are frequently cited comorbid conditions (

5 ). Preliminary evidence further suggests that migraines may co-occur with bipolar II disorder more often than with bipolar I disorder, implying that the overlap between these disorders may represent a subphenotype of bipolar disorder (

6 ). Finally, compelling clinical evidence indicates that the relative risk for obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus type II is increased and independently exerts a deleterious effect on the course of bipolar disorder (

7 ). Notwithstanding these prior observations, relatively few clinical studies have purposefully examined the effect of medical comorbidity on bipolar disorder in a large community-based epidemiologic study.

This post hoc analysis aimed to ascertain the prevalence and prognostic implications of predetermined comorbid general medical disorders amongst persons who screen positive for a manic episode. The burden of medical comorbidity on employment, functional role, psychiatric care, and medication use was examined within this subpopulation of individuals.

Methods

The Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and Well-Being (82-617-XIE) is a component of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) and was conducted by Statistics Canada in 2002 (www.statcan.ca/english/sdds/instrument/5015q1v1e.pdf). The survey used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview found in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health 2000 (WMH-CIDI). Respondents were residents of private dwellings; a multistage stratified cluster design was used to sample dwellings. Most interviews were conducted in person (86 percent); the others were conducted by telephone. The responding sample totaled 36,984 people aged 15 years or older; the response rate was 77 percent. The data were weighted to be representative of the household population of the ten provinces in Canada in 2002.

On the basis of WMH-CIDI screening criteria, the survey collected information on lifetime and past-12-month prevalence of various mental disorders (that is, major depressive episode, manic episode, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, alcohol and drug dependence, gambling, suicide, and abnormal eating behavior), self-reported height and weight, previously diagnosed medical disorders (migraine, arthritis, asthma, gastric ulcer, hypertension, chronic bronchitis, thyroid disease, multiple chemical sensitivities, heart disease, diabetes, Crohn's disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, cataract, and cancer), access to and use of mental health care services, admissions to hospitals and the use of medications, disability associated with mental health, and factors that influence or are influenced by mental health, such as work and lifestyle (www.statcan.ca:8096/bsolc/english/bsolc?catno=82-617-X).

The survey also collected information on determinants and correlates of mental health, such as sociodemographic information, income, stress, level of leisure-time physical activity, and social support.

Respondents who screened positive for a manic episode were identified; data were subsequently analyzed for two groups: respondents endorsing having had a lifetime manic episode (positive screens, indicative of a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder) and respondents without a lifetime manic episode (reference group). Level of household income was dichotomized into two categories (low or not low) according to the number of people in the household; low income was defined as a net annual income from all sources less than $15,000 (Canadian dollar [CAD]) for one or two people in the household, less than $20,000 (CAD) for three or four people, and less than $30,000 (CAD) for five or more people. In 2002 the exchange rate was $1.53 (CAD) to $1.00 (U.S.) Prevalence estimates of selected self-reported physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders were produced and compared on the basis of a manic episode endorsement. No data on smoking status were collected for the survey.

Within the subpopulation that screened positive for having had a manic episode, selected characteristics were examined; these included physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders; indices of occupational, social and personal functioning; psychiatric care utilization; and medication use.

All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS statistical software, release 8.02. Variables for analysis were selected a priori on the basis of previous research. To account for the complex sampling design of the CCHS, the data were weighted and coefficients of variation on estimates and significance of differences between estimates were calculated by using the bootstrap technique. The level of statistical significance was defined as p<.05.

Results

A total of 36,984 persons completed the CCHS survey. A positive screen for a lifetime manic episode was reported among 938respondents. Weighted to the age distribution of the household population in the ten provinces in Canada in 2002, this represents 589,000 (2.4 percent) persons aged 15 years or older.

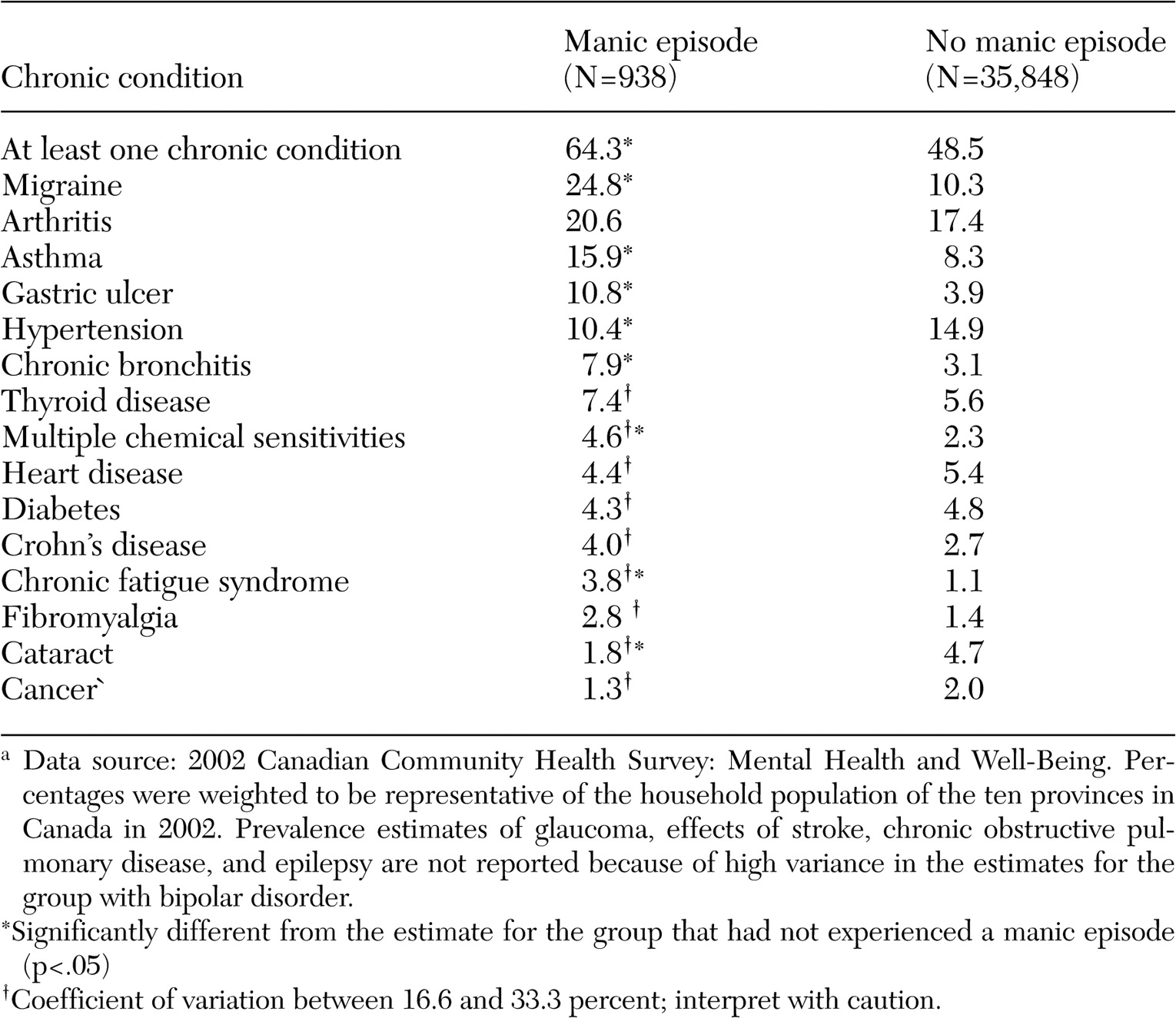

Physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders for all respondents are presented in

Table 1 . The proportion of the population with positive screens for a manic episode who also reported at least one (of a possible 19) comorbid physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders (64.3 percent) was significantly higher (p<.05) than that of respondents who screened negative for a manic episode (48.5 percent). The proportion of the population with positive screens who had three or more comorbid physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders was 16.9 percent, compared with 11.6 percent in the reference group (p<.01). Among respondents with a positive screen, the prevalence of comorbidity was disproportionately high at all ages.

Compared with the reference group, the group with a positive screen for a manic episode had a higher prevalence of migraine(24.8 percent compared with 10.3 percent), asthma (15.9 percent compared with 8.3 percent), gastric ulcer (10.8 percent compared with 3.9 percent), chronic bronchitis (7.9 percent compared with 3.1 percent), multiple chemical sensitivities (4.6 percent compared with 2.3 percent), and chronic fatigue syndrome (3.8 percent compared with 1.1 percent). (All differences were statistically significant at the level of p<.05.) When the analyses were adjusted for socioeconomic status and obesity, the likelihood of comorbidity was higher for the population with a positive screen; the odds of at least one comorbid condition in the group that screened positive were nearly three times as high as the odds for the reference group.

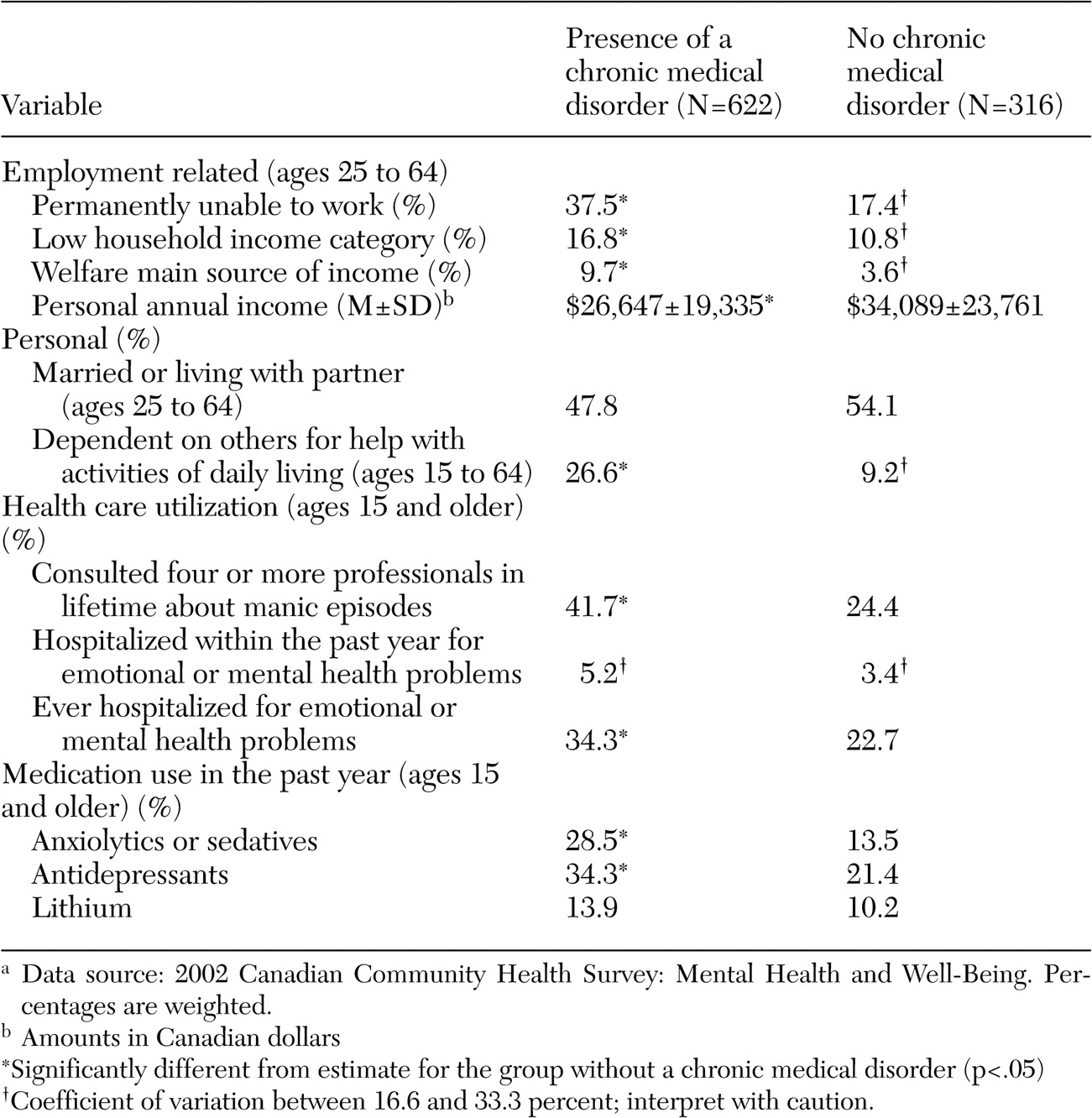

In the subpopulation that screened positive for at least one manic episode, the presence of any comorbid physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorder was associated with employment dysfunction. Among persons with at least one comorbid physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorder, the likelihood of being permanently unable to work was more than twice as high for those with a such a diagnosis than for those without such a diagnosis (37.5 percent compared with 17.4 percent; p<.05) (

Table 2 ). Comorbidity was also associated with low income and receiving social assistance or welfare as the main source of income. Not surprisingly, the average annual income of persons with at least one comorbid condition was strikingly lower (about $7,400 [CAN] lower) than that of persons without such a diagnosis (

Table 2 ).

Comorbidity was also predictive of a higher likelihood of personal dependency (

Table 2 ). The percentage of people who reported a need for assistance from others with at least one activity of daily living (personal care, preparing meals, light housework, getting around the home, running errands, or paying bills) was about three times higher among those with comorbidity than among those without (26.6 percent compared with 9.2 percent; p<.05).

A history of mania coupled with a physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorder was associated with higher consultation rates, greater medication use, and an increased likelihood of hospitalization. A higher proportion of people with a physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorder had consulted four or more different professionals regarding their mental or emotional health, compared with those without such a diagnosis (41.7 percent compared with 24.4 percent; p<.05). The percentage of people who had ever been hospitalized for their emotional or mental health was significantly higher for people with a physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorder than for those without such a diagnosis (34.3 percent compared with 22.7 percent; p<.05). Finally, the proportions of people with a physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorder who had used anxiolytics or antidepressants within the past year significantly exceeded the corresponding proportions among people without such a diagnosis.

A dose-response relationship was suggested insofar as a greater number of physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders was associated with higher levels of dysfunction and service utilization among respondents who screened positive for a lifetime manic episode. The number of physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders was significantly associated with elevations in the odds of being dependent on others for activities of daily living, being unable to work, ever being hospitalized for mental health care, having consulted four or more mental health professionals, and using psychotropic medication (antipsychotics, anxiolytics, antidepressants, lithium, sedatives, or stimulants) (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first cross-national epidemiologic population-based investigation to report the overlap and reciprocal interaction between comorbid general medical disorders and functional outcomes in a community sample of persons with bipolar disorder. Persons with bipolar disorder reported a higher prevalence of physician-diagnosed chronic medical disorders than those without bipolar disorder. Having a chronic medical disorder diagnosed by a physician was associated with less successful employment outcomes, greater dependency on others for assistance, and higher utilization of mental health care services, including hospitalization.

Our results supplement and extend existing data describing the clinical overlap and interactions between bipolar disorder and medical comorbidity. A previous descriptive study of 4,310 veterans who received at least one inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder reported a high prevalence of comorbid medical conditions, including cardiovascular (hypertension) and endocrine (hyperlipidemia and diabetes) diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, infectious disease (hepatitis C), and musculoskeletal conditions (for example, low back pain) (

8 ). More than one-third of the respondents with bipolar disorder were given a diagnosis of three or more comorbid medical conditions; the risk for medical comorbidity was significantly higher in the group with bipolar disorder at an earlier age (compared with the reference group). However, interactions between medical comorbidity and the functional domain trajectory were not reported (

8 ).

There are several causal pathways that may be salient to the overlap between bipolar disorder and medical comorbidity. For example, patients with bipolar disorder have many risk factors for general medical disorders (

9 )—such as insufficient access to primary and preventive health care, lower socioeconomic status, poor adherence to medical regimens, smoking, habitual inactivity, substance abuse, comorbid binge-eating disorder, adverse childhood experiences (that is, abuse), and high caloric intake. Moreover, affective disease activity is coupled to immunoinflammatory and counterregulatory hormone activation, which may result in end-organ damage via allostasis (

10 ). Iatrogenic causes are also possible; that is, medications for the management of bipolar disorder have a panoply of adverse effects on physical health—for example, hypothyroidism (lithium), diabetes mellitus type II (second-generation antipsychotics), and polycystic ovarian disease (divalproex ) (

11 ).

There are several methodological limitations to this investigation that indicate that results should be interpreted with caution. Data on the primary outcomes of interest were entirely gathered by self-report with no third-party corroboration or verification through respondent records. The WMH-CIDI is a well-validated screening tool for psychopathology and has been previously incorporated into several population-based epidemiology studies. The WMH-CIDI has a higher sensitivity for euphoric manic presentations but may underestimate the prevalence of mixed (dysphoric) mania (

12 ). It is notable, however, that the prevalence estimates for bipolar disorder in the CCHS were similar to those in other population-based epidemiologic studies (

13,

14 ).

A fundamental limitation of this investigation is that the analysis was conducted post hoc; the CCHS was not specifically designed in anticipation to our analysis. Notwithstanding, we feel that it is unlikely that respondents who screened positive for a manic episode would disproportionately and systematically overstate all areas of occupational and personal role dysfunction, along with medical service utilization. These data were collected cross-sectionally; therefore, direction of causality cannot be determined. Moreover, several variables may be collinear (for example, employment, income, welfare, and assistance). It could also be conjectured that the increase in medical service utilization among persons with a physician-diagnosed medical disorder reflects the greater likelihood that separate medical conditions are separately investigated and managed. We believe, however, this is most unlikely insofar as most investigations reporting on health care services among persons with mental disorders describe insufficient access and attention to somatic health matters (

15 ).

Conclusions

Health care providers in general medical settings need to be familiar with the clinical overlap and interactions between general medical conditions and chronic psychiatric disorders. Patients with affective disorders are an at-risk group for myriad medical disorders, which are often undiagnosed and subsequently left untreated. For practitioners in mental health settings, opportunistic screening for general medical disorders and incorporation of appropriate preventive measures should be sine qua non.