The psychiatric vignette

The psychiatric scenario has four stages where questions are asked of participants. The first stage evaluates preferences for providing medication against one's will. The vignette reads as follows: "Imagine that a person with a serious mental illness becomes frightened of others, upset, and confused. Over a few weeks things get worse and the person is placed in a hospital. He believes that other people want to hurt him and that the food is poisoned. He refuses to take any medications. At this point, he is so sick that he is unable to make good decisions. If medications will help this person to get better, is it OK to give them to him against his will? If this were you, would you want medication to be given to you against your will? If you had a person who was your health care proxy, would you want your proxy to approve medication for you, even if you were refusing it?"

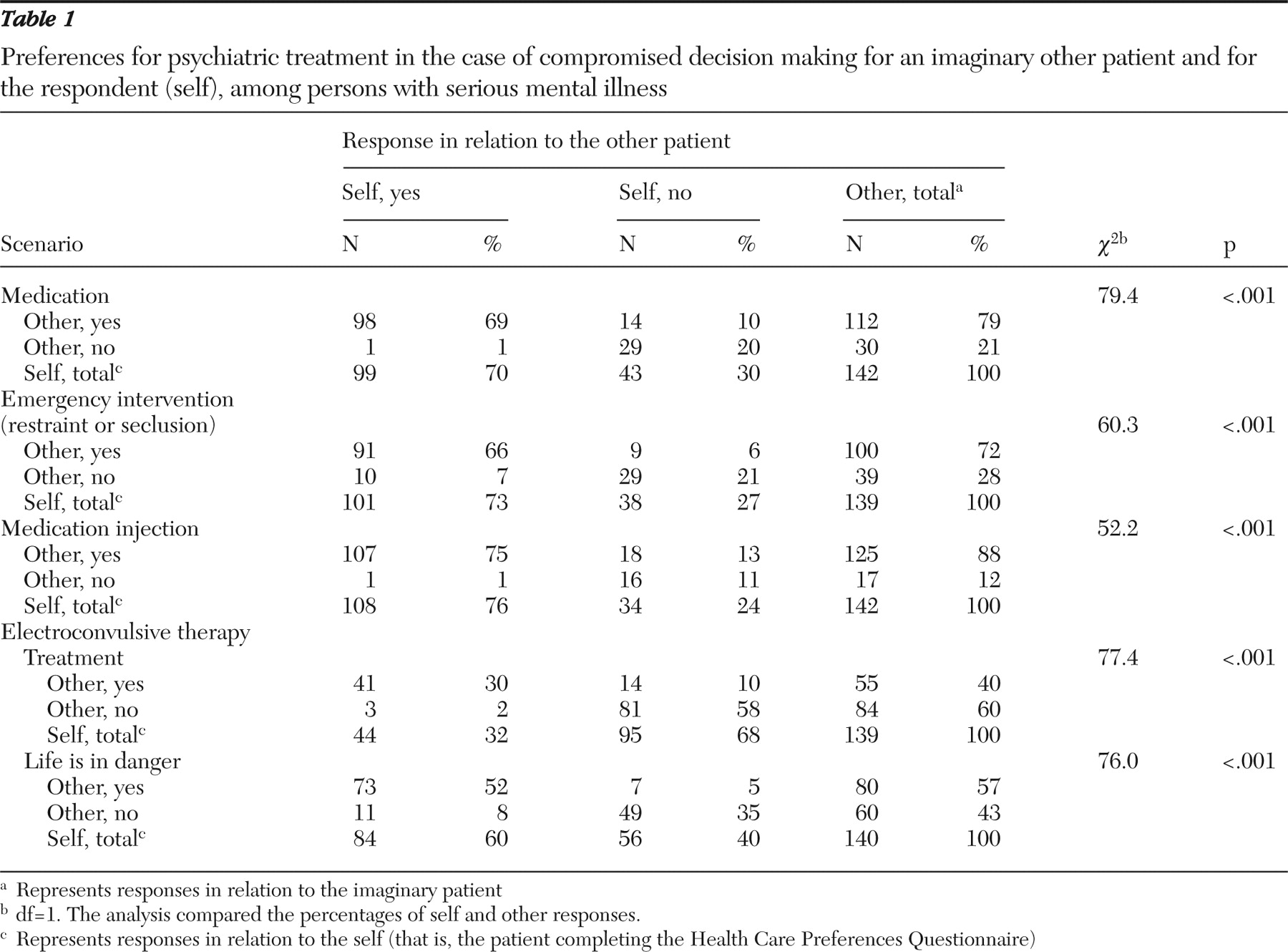

As shown in

Table 1, a total of 112 participants (79%) believed that medication should be given to the imaginary other person; however, only 99 participants (70%) would want to receive the medication against their own will. There were significant correlations between approval for providing the medication and greater understanding of the interview (r=-.188, p<.05), adherence to medications (r=-.180, p<.05), and older age (r=-.200, p<.05). Finally, having a proxy was positively correlated with believing that the proxy should approve the medication (r=.228, p<.01).

The second stage of the scenario describes increased aggression and the need for emergency interventions. The vignette continues as follows: "Let's say this person assaulted a hospital employee because he is afraid the employee wants to hurt him, even though that employee was trying to help. In this situation, should the physicians use an emergency intervention, such as putting the person in a locked quiet room or limiting his movements by tying him down to a bed with restraints?"

Participants had similar responses for self and other in the use of emergency interventions. Most believed that emergency interventions were appropriate measures in this situation for the imaginary other person (72%) or for themselves (73%). Among the 101 participants who said that emergency interventions should be administered, seclusion in a locked quiet room was preferred over physical restraints (N=81, or 80%, versus N=20, or 20%). Affirmative responses to the use of restraint or seclusion were correlated with greater comfort with the interview (r=.244, p<.01) and having picked a health care proxy (r=.191, p<.05).

The third stage of the scenario asks about involuntary medications that the patient has been refusing to take and that could improve his or her thinking. "Now he is so confused and fearful that he is attacking others. In this situation, should the physician order an injection of medication that would calm the person and that might help to treat his mental illness?"

Most participants would want the physician to provide an injection of medication under these circumstances. However, participants were more likely to want the physician to give the injection to the imaginary person than to themselves (88% versus 76%). Here, 94 of 145 participants (65%) had specific medications that they would never want to receive. The medications that were most commonly cited included haloperidol (indicated by 32 participants) and thorazine (mentioned by 24 participants).

Younger age (r=.181, p<.05) and nonadherence to medication routines (r=.191, p<.05) were associated with refusing specific medications. A total of 118 participants (81%) also had preferences regarding which medications were the most appropriate. Having lower mental well-being, according to the mental component of the SF-12 (r=.222, p<.01), or a mood disorder (r=-.197, p<.05) instead of a thought disorder was associated with preferences about the best medication to treat one's mental illness. Finally, adherence to medication was positively correlated with choosing that the health care proxy would inform the physician or judge about particular medication preferences (r=-.167, p<.05).

The final stage of the scenario addresses the provision of electroconvulsive therapy against the patient's wishes. "Now let's imagine that this person's mental illness symptoms might be quickly and effectively treated with ECT (electroconvulsive therapy, or 'electric shock therapy') treatments. In this situation, he is refusing ECT. If a judge says that the person is not able to decide for himself at this time because of his illness, is it OK to give these treatments?"

The scenario goes on to ask, "If this patient's situation worsened so that his life was in danger due to his mental illness (for example, he is in danger of dying from starvation or self-injury) and other treatments were not helping, do you think electric shock treatments should be ordered, even if he were refusing them at the time?"

Most participants were unwilling to receive ECT as a potential quick and effective treatment (other, 40%; self, 32%). They were more likely to agree to ECT when life was in danger because of psychiatric symptoms (other, 57%; self, 60%). Worse physical well-being was associated with believing that the judge should decide to provide the participant with ECT (r=.180, p<.05). In addition, more medical problems were associated with believing that ECT should be ordered in a life-threatening situation (r=-.202, p<.05).

Understanding

Clinician interviewers indicated that most participants understood HCPQ questions (extremely well or very much, N=90, or 68%; somewhat, N=34, or 26%; not at all or not very much, N=9, or 7%). Greater understanding was associated with affirmative responses regarding the receipt of medications via injection (r=-.259, p<.01) and a wish to have the health care proxy tell a judge (r=-.214, p<.05) or physician about ECT preferences (r=-.236, p<.01). In contrast, the interviewer's subjective perception of the participant' impaired decision making (N=17, or 13%) was correlated with negative responses to providing medications against one's will (r=.200, p<.05) or having the proxy recommend medications against one's will (r=.202, p<.05), receiving medications by injection (r=.265, p<.01), and wanting the proxy to tell the physician about one's wishes regarding ECT (r=.191, p<.05).