Adolescents with drug and alcohol problems smoke tobacco at roughly 1.5 times the rate of their counterparts without such problems (

1 ). However, substance abuse treatment programs often do not target smoking, despite its long-term health risks (

2 ). No systematic analyses have established an association between smoking and recovery from drug and alcohol problems after drug treatment for adolescents.

We examined smoking rates by recovery status among youths admitted to one of ten treatment programs participating in the Adolescent Treatment Models evaluation between 1998 and 2001 (

3 ). Youths were followed for 12 months. Smoking behaviors were measured at intake and 12 months. Recovery status was measured at 12 months.

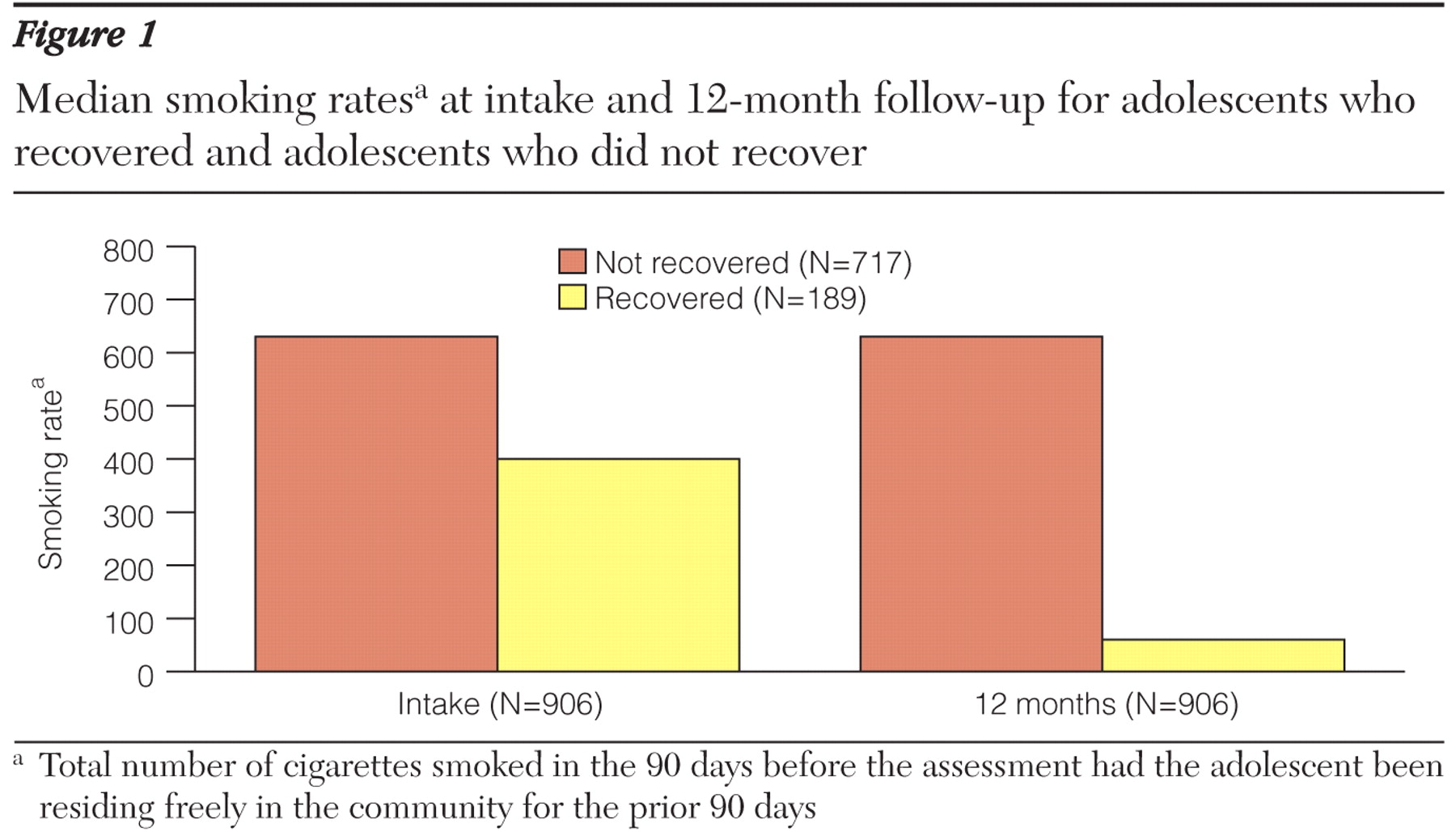

We measured the total number of cigarettes smoked in the 90 days before intake and follow-up. We calculated smoking rate per number of days spent free in the community to control for the effects of time spent in institutional settings, where smoking is typically prohibited. We then multiplied this rate by 90 to estimate the expected number of cigarettes smoked had the adolescent been residing in the community for the prior 90 days. We compared these rates between youths who were or were not in recovery at the follow-up, where recovery was defined as having no recent substance use, no history of symptoms related to a substance use disorder in the past month, and no recent stays in jails or detention centers.

In univariate analyses, adolescents who recovered had significantly lower median rates of smoking at the follow-up than youths who did not recover (p<.001) (

Figure 1 ). Median change in smoking rates in 12 months was significantly different for both groups (p<.001) and was significantly less than zero in the recovered group (p<.001). These findings held after we controlled for age, race, baseline smoking rate, and emotional problems at intake and after we removed data of six outliers.

Our data suggest that adolescents who recover from substance problems are not at greater risk of smoking escalation, compared with those who did not seem to benefit from treatment. Our cohort on average decreased their smoking. Adolescents who do poorly in treatment may bear the additional health risks of continued high rates of smoking after treatment. These youths may require targeted smoking intervention (

3 ), which may be a critical component in promoting their health and longevity.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants 1R49-CE000574, 1R01-DA16722, and 1R01-DA 015 697 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The authors report no competing interests.