According to Lilla Watson, as cited in Wadsworth and Epstein (

1 ), "If you have come to help me you are wasting your time. But if you've come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together."

Adoption of a consumer perspective on recovery in the delivery of case management services is now widely accepted in policy, and recovery principles increasingly are being incorporated into practice at the level of service delivery. To this extent the "recovery movement" has been a success. However, research that assesses the effectiveness of service models that incorporate a recovery orientation is relatively new. Even though consumer participation is a cornerstone of the recovery movement, it has been extended to the research process in only limited ways. As a result, evaluations run the risk of basing success on criteria that are not central to the concerns of consumers.

In this Open Forum, recovery refers to "establishment of a fulfilling, meaningful life and a positive sense of identity founded on hopefulness and self determination" (

3 ). Recovery is becoming a visionary concept for guiding mental health service policies in many nations (

4,

5,

6 ), but researchers have yet to adequately consider its implications for evaluation of case management. Case management is defined broadly in this article as a means of coordinating the care of people in the community with severe mental illness (

7 ). This study was a general investigation of the extent of consumer involvement in service evaluation and focused on recovery concepts across all case management models (including intensive, clinical, strengths based, and assertive community treatment).

Outcome evaluations reconsidered

Historically, evaluations of case management practices have typically been undertaken within paradigms of outcome research, in which assessments are grounded in a medical model, primarily focusing on functional status, symptoms, or hospital admissions (

8,

9 ).

Illness- and disability-focused outcomes retain relevance within a recovery framework. Helping people gain mastery over symptoms and preventing hospitalizations nurture hope for the future and can assist in their pursuit of personal goals (

10 ). However, recovery-oriented approaches adopt a more holistic perspective and incorporate the development of positive mental health, which includes personal goal attainment, presence of meaningful roles, coping, hope, empowerment, and self-esteem (

11,

12 ). Closer consideration of illness-focused outcomes is required to provide enhanced meaning from a recovery framework. For example, it may be important to establish whether individuals believe they have gained control over symptoms, rather than focusing entirely or even primarily on the degree of symptom reduction. This perspective raises significant challenges for research design and measurement.

Assessments of outcomes reflecting positive mental health are limited, at best, in existing evaluations. Quality of life has been investigated in some instances (

13,

14 ). However, a single measure of quality of life inadequately represents the complexity of an individual's recovery process. Studies sometimes include a measure of client satisfaction (

15,

16,

17 ). However, the validity of such measures is questionable when consumers are not involved in their development (

18,

19 ) and when the measures focus on the extent to which current practices are endorsed and fail to assess dissatisfaction (

20 ). Also, these measures by themselves do not address issues of recovery. With these deficiencies in mind, Liberman and colleagues (

21 ) have provided an operational or outcome-based definition of recovery that requires assessments of outcomes in dimensions of symptomatology, vocational functioning, independent living, and social relationships. Clearly, their definition moved the research beyond an illness focus and includes outcome domains that consumers have often identified as important, making it potentially useful in outcome evaluations.

Literature review

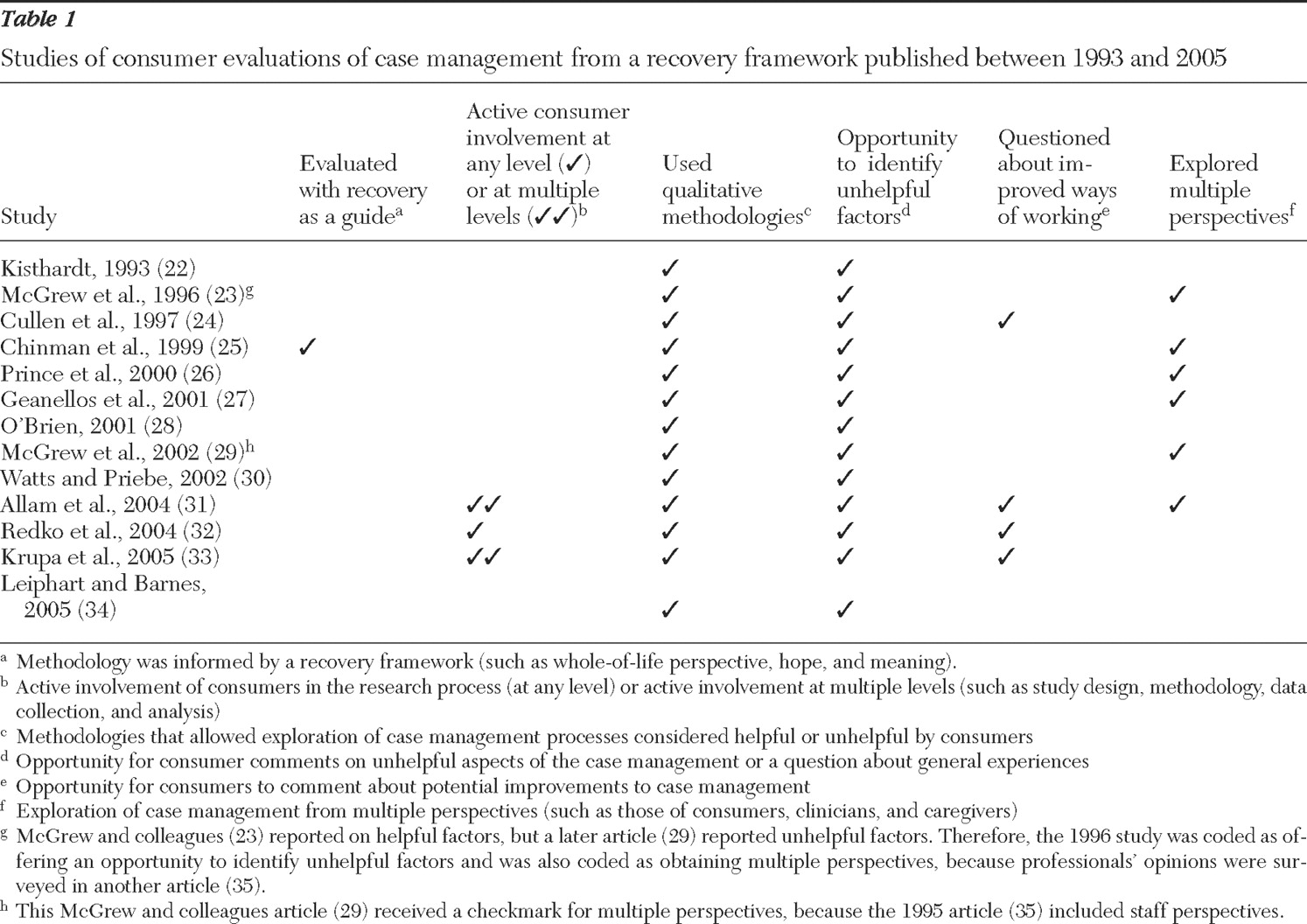

We examined research on case management that draws on consumer perspectives. This review clarifies the extent of consumer involvement and whether evaluations were informed by recovery perspectives. Searches of Ovid Medline (1966–2006), PsycINFO (1967–2006), and Cinahl (1982–2006) databases were conducted with combinations of the following terms: assertive community treatment, case management, assertive outreach, strengths model, rehabilitation model, ICM and intensive case management, client perspectives, participant perspectives, service users, consumer priorities, and client attitudes. Additional searches used terms from identified articles, and we checked their reference lists to locate other articles. The search focused on articles that report on studies explicitly aimed to capture consumer perspectives. Evaluations that incorporated only satisfaction ratings or similar methodologies were not included in the primary analyses because of the limited extent to which they can offer a consumer perspective. Studies were assessed with the consumer involvement criteria summarized in

Table 1 .

The search identified the 13 studies listed in

Table 1 (

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34 ). Studies are ordered chronologically by year and then according to the total number of consumer criteria, indicated by checkmarks, that were met. A companion paper (

35 ) to McGrew and colleagues' papers (

23,

29 ) surveyed clinicians' perspectives and was taken into account when providing checkmarks. Nine of the studies focused on evaluations of assertive community treatment, which is not surprising given the popularity of this model (

36 ). Key observations are summarized below.

Few studies of active consumer participation

Only two studies involved consumers extensively throughout the research process (

31,

33 ), and another involved consumers only in data collection (

32 ). None of the reviewed studies provided direct evidence on whether the involvement of consumers in research has an impact on findings. However, researchers have suggested that collaborating with consumers in the design phase may help to ensure that areas of importance to them are addressed (

37 ). Consumers also may provide more honest, and perhaps even negative, responses when data are collected by peers rather than staff or researchers (

29,

38,

39 ). Therefore, consumers' involvement in data analysis may help ensure that the meaning of results is correctly interpreted (

31,

37,

40 ).

Benefits of enhanced validity from consumer participation in data collection are now starting to be recognized in general medicine (

41,

42 ). For instance, systematic reviews of electroconvulsive therapy have shown that compared with clinician-led studies, consumer-led studies show lower rates of perceived benefit (

43 ). There is a need to systematically assess the impact of consumer involvement on the nature and validity of case management evaluations.

Qualitative methodologies

All of the studies included in

Table 1 had some form of qualitative assessment, providing a rich source of information, including dissatisfaction. In a study by Redko and colleagues (

32 ), consumers answered open-ended questions about what they liked best and least and what they would change; they also completed a satisfaction scale. Open-ended questions allowed consumers to express satisfaction and dissatisfaction about the quality of relationships with case managers and the degree of involvement in their own treatment. Consumers expressed concern over high staff turnover, reporting that it interfered with effective care and relationship quality.

McGrew and colleagues (

29 ) used open-ended questions to assess what consumers liked least about assertive community treatment. Some consumers reported that practices were too paternalistic and overly focused on medications. Krupa and colleagues (

33 ) undertook a participatory action study in collaboration with consumers, reporting results from focus groups with 52 consumers. Consumers highlighted continuity of service provision and 24-hour support as key reasons for positive change. Relationships described as "helpful" were caring, collaborative, built trust, and conveyed belief in clients' potential. Examples included case workers who collaborated in goal setting, encouraged active contribution to their community, helped consumers identify opportunities for growth, addressed poverty, and met everyday needs. Consumers emphasized development of self-reliance and independence and active pursuit of well-being. In contrast, areas of dissatisfaction included a low emphasis on work, education, and training; authoritative or controlling relationships; and excessive focus on weaknesses rather than strengths.

The wide range of observations in these studies may not have been revealed without the opportunity for responses to emerge from open-ended questioning. Qualitative studies by their very nature are concerned with meaning, especially the subjective understandings of participants, and allow for the identification of emergent categories and themes because they do not solely rely on a priori concepts and ideas (

44 ). Creating opportunities for comment about unhelpful as well as helpful aspects is particularly important, because doing so highlights areas that may be critical to service improvement. Open-ended questions do not, of course, guarantee either an adequate representation of consumers' views or embodiment of a recovery perspective. The nature of a question carries assumptions about the importance of the targeted issue to consumers. However, closed-ended questions assume that the key response options have been captured. Such an assumption is particularly risky when professionals generate questions and consumers have little or no say in question selection (

45 ). Although we recognize that issues relating to consumer participation and qualitative methodology are far more complex than differences between closed- and open-ended questions, this example illustrates the importance of appropriate methodology when evaluating case management from a consumer or recovery perspective.

Data obtained from focus groups, open-ended survey questions, or other qualitative methodologies offer greater opportunity for consumers to emphasize issues of perceived importance for their individual recovery (

46 ). Several recovery-related issues are raised by the responses in the studies discussed above, even though questions were not specifically focused on recovery. For example, the quality of the therapeutic relationship—an issue raised in the study by Redko and colleagues (

32 )—is seen as a key factor in facilitating recovery (

11,

47,

48 ). A perception that staff turnover is high raises a recovery issue. Whereas continuity, one-on-one relationships, and staff availability are thought to assist recovery, discontinuity, such as turnover, hinders it (

11,

49 ). The Redko study (

32 ) revealed perceptions of paternalism and an excessive focus on medication, which indicate characteristics that appear to hinder recovery (

11,

50 ). Characteristics of helpful relationships and positive features of assertive community treatment that were identified by consumers in the study by Krupa and colleagues (

33 ) map onto features that are seen as facilitating recovery—for example, development of personal control, meaningful activities, and a focus on the person beyond the illness (

11,

47,

51 ). Similarly, areas that consumers identified as dissatisfying, such as a low emphasis on work, education, and training and an excessive focus on weaknesses rather than strengths, have been recognized as hindrances to recovery (

11 ).

Looking toward the future

This section highlights some possible ways in which researchers may align future evaluations of case management with recovery visions for service delivery. Qualitative research methods are expected to have an increasing role in future evaluations of case management, particularly as increasing emphasis is placed on participatory approaches and service improvement in addition to (or instead of) more traditional outcome designs. Decisions concerning methodological approaches, such as undertaking pure outcome-based research, entail assumptions about whether recovery is best conceptualized primarily as an outcome or as a process. Logically, it must be both process and outcome. Where possible, the preferable approach may be to consider methodological designs that attempt to capture potential outcome indicators of recovery supplemented with process data. Research design decisions should be made in collaboration with consumers.

Over time, evaluation research has been reconceptualized away from more traditional summative evaluation focusing on outcomes, or overall value of programs, toward formative evaluation. Formative evaluation, in contrast to summative evaluation, focuses more on process to adjust or inform the improved conduct of a program (

56 ). Several authors have emphasized the essential role that consumers must play in driving improved mental health services (

57,

58 ). Participatory approaches to evaluation are important within a recovery framework for many reasons, perhaps primarily to honor and respect the knowledge and lived experience that come from recovering from a mental illness. Qualitative methods of inquiry by their very nature are highly appropriate for studying processes, which are central to program improvement and are also accessible to the lay person, making them particularly suitable for participatory means of inquiry (

44 ). Furthermore, consumers most commonly view recovery as a process instead of an outcome (

59 ).

More specifically we recommend that researchers consider the potential benefits of forming partnerships with consumers extensively, throughout the evaluation process. Practical examples of successful participatory projects are available, as well as guidance on issues such as providing training and support for individuals (

1,

31,

37,

40 ). Empowerment evaluation and participatory action research may be particularly relevant means of inquiry within this context, with an emphasis on breaking down the power relationship between the researcher and the researchee as well as on improving services (

60,

61,

62,

63 ). Empowerment evaluation involves the use of evaluation concepts, techniques, and findings to support improvement and self-determination among participants (

64 ). Traditionally used within the context of program evaluation, empowerment evaluation has also been applied to organizations, communities, societies, cultures, and individuals (

65 ). Participatory action research has been described as a form of applied research that actively encourages people in the organization or community under investigation to participate with professional researchers throughout the entire research process, from problem formulation to the application and assessment of results (

66,

67 ).

When planning the design of evaluations, it may be helpful to discuss two broad research questions: How do case management practices support or hinder individuals' recovery processes? How might case management practices be improved to better support individuals' recovery processes?

When undertaking outcome evaluations of case management, researchers should discuss with consumers and professionals at initial stages of research design the relevance of both traditional symptom- or function-based assessments and recovery-related measures. Researchers could use key recovery concepts, such as hope, personal goal attainment, and empowerment (

3,

11,

12 ), to assist in selection of outcome measures. Examples of scales that attempt to measure these concepts are the Hope Scale (

68 ) and the Consumer Empowerment Scale (

69 ). Items from these measures, respectively, include "I can think of ways to get things in life that are most important to me" and "People have a right to make their own decisions, even if they are bad ones."

If case management practices are to support individuals toward recovery, it is clear that assisting consumers in areas such as identifying and reaching valued directions in life, as well as having a say in decisions and taking risks, are likely to be important. Collaborative goal technology (

70 ) is a recent adaptation of goal attainment scaling (

71 ), which is a goal-striving intervention developed specifically to support the recovery and autonomy of people with mental illness. The overall goal index from collaborative goal technology could be a useful outcome indicator within case management settings. Repeated administration of measures such as the Recovery Assessment Scale (

72 ) may provide an indication of an individual's progress through recovery over time. Alternatively, Liberman and colleagues (

21 ) have provided an operational, outcome-based definition of recovery (discussed above), which could be useful as part of outcome evaluations. Recovery concepts could also guide the development of research questions for interviews or focus-group discussions when evaluating case management practices with consumers and other stakeholders.