Chi square analysis

For the use of personal care services, chi square analysis identified significant differences between the treatment and control groups. An objective outcome measure showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups: 102 clients (94%) in the treatment group versus 92 (77%) in the control group received paid care at nine months ( χ 2 =11.86, df=1, p<.001). In addition, we performed the same chi square analyses for 25 outcome measures, covering satisfaction with paid caregivers' reliability and schedules, satisfaction with the relationship with the paid caregiver, perception of caregivers' attitudes, satisfaction with paid caregivers' performance and transportation assistance, and satisfaction with overall care arrangements, as well as client life satisfaction, unmet needs, adverse events, health problems, and general health status.

Out of the 25 outcome measures, 11 belong to the area encompassing adverse events, health problems, and general health status. Examples are "fell in past month," "saw a doctor because of fall, cut, burn, scald, etc." In this area, our chi square analyses yielded the same findings as did the earlier overall program evaluation by Mathematica Policy Research (MPR) (

8,

9 ): there were no statistically significant differences between consumers in the treatment and control groups, indicating that under the CCDE program, care was at least as safe as agency-directed care. In terms of other outcome measures in other areas, chi square analysis demonstrated positive, although not always statistically significant, effects of the CCDE program.

To save space, we do not report the chi square analysis results here. To yield conservative results, we needed to control for the effect of baseline characteristics through logistic regression analysis.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis results

In multivariate logistic regression analyses, we used hierarchical analysis strategy. As the first step, we included the clients' baseline demographic characteristics, health and functioning, use of personal assistance, and satisfaction with care. Then we added treatment status to the model to estimate the "pure" effect of the CCDE program on use of personal care services and quality of service after removing the effects of all the variables that were controlled. As shown in

Table 2 to

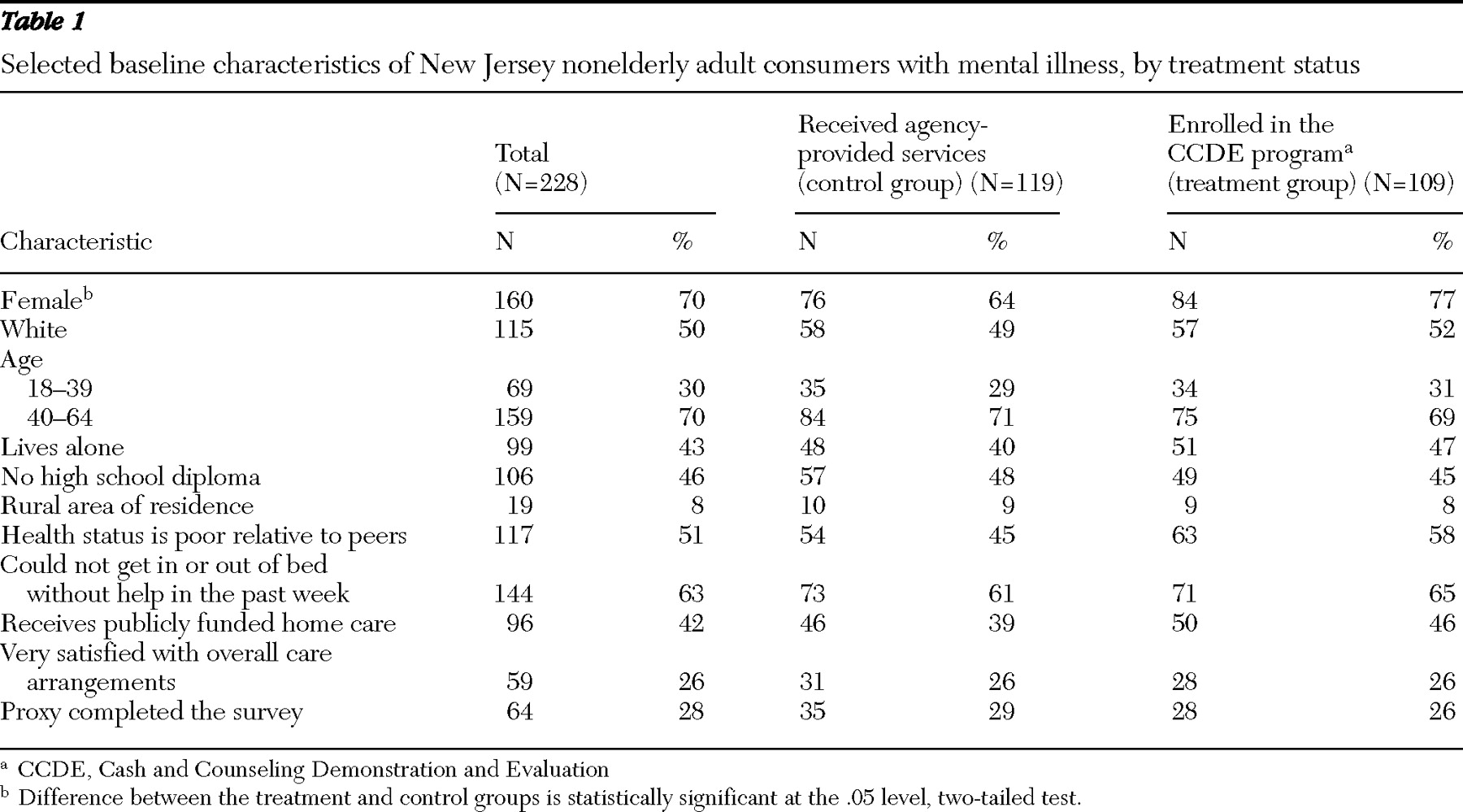

Table 5, the covariates that were controlled include all the baseline characteristics reported in

Table 1 except for "proxy completed the survey." Our initial logistic regression analyses included all of the 25 outcome measures used in chi square analyses. To save space,

Tables 2 to

Table 5 present the results for 16 selected outcomes from the multivariate logistic models. The full results for other outcome measures and chi square analysis results are available upon request.

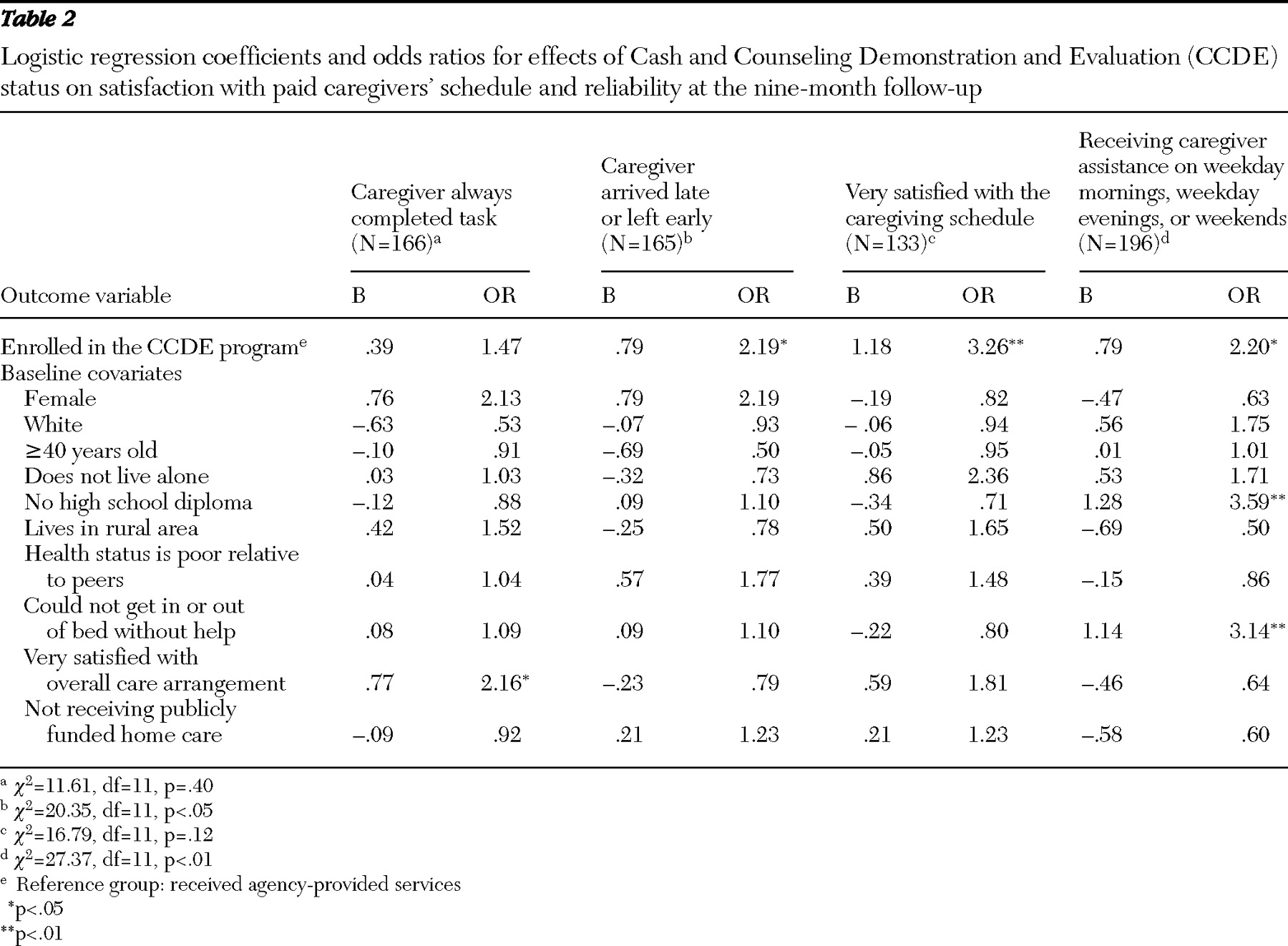

Table 2 presents logistic regression coefficients and odds ratio for effects of the CCDE program on four outcome measures reflecting client satisfaction with caregivers' schedule and reliability.

As mentioned earlier, all the outcome variables are dichotomous. The first outcome measure is "always completed task." Always is coded as 1 and otherwise is coded as 0. As shown in

Table 2, 166 participants were involved and had complete data. Out of the ten baseline characteristics used as control variables (covariates), one has a significant and positive effect—very satisfied with overall care arrangement. With the covariates in the model, consumers in the treatment group had a 47% (odds ratio=1.47) greater likelihood of saying that the paid caregivers always completed the task, compared with those in the control group. However, after the analyses controlled for the effects of baseline covariates, the difference was no longer significant.

The second outcome measure is never arrived late or left early. As shown, with the ten covariates in the model, consumers in the treatment group had more than twice a greater likelihood of indicating that the caregiver never arrived late or left early, compared with those in the control group (p<.05).

The third outcome measure is whether the consumer was satisfied with the caregiver's schedule for providing service. After controlling for the effects of the ten covariates, consumers in the treatment group had a significantly higher likelihood of claiming that they were very satisfied, compared with those in the control group (p<.01).

The fourth outcome is an objective outcome measure: whether consumers received their caregivers' service on a weekday morning, weekday evening, or weekend. Again, there was a statistically significant difference between the groups, with the treatment group being more than twice as likely to receive services during these times (p<.05).

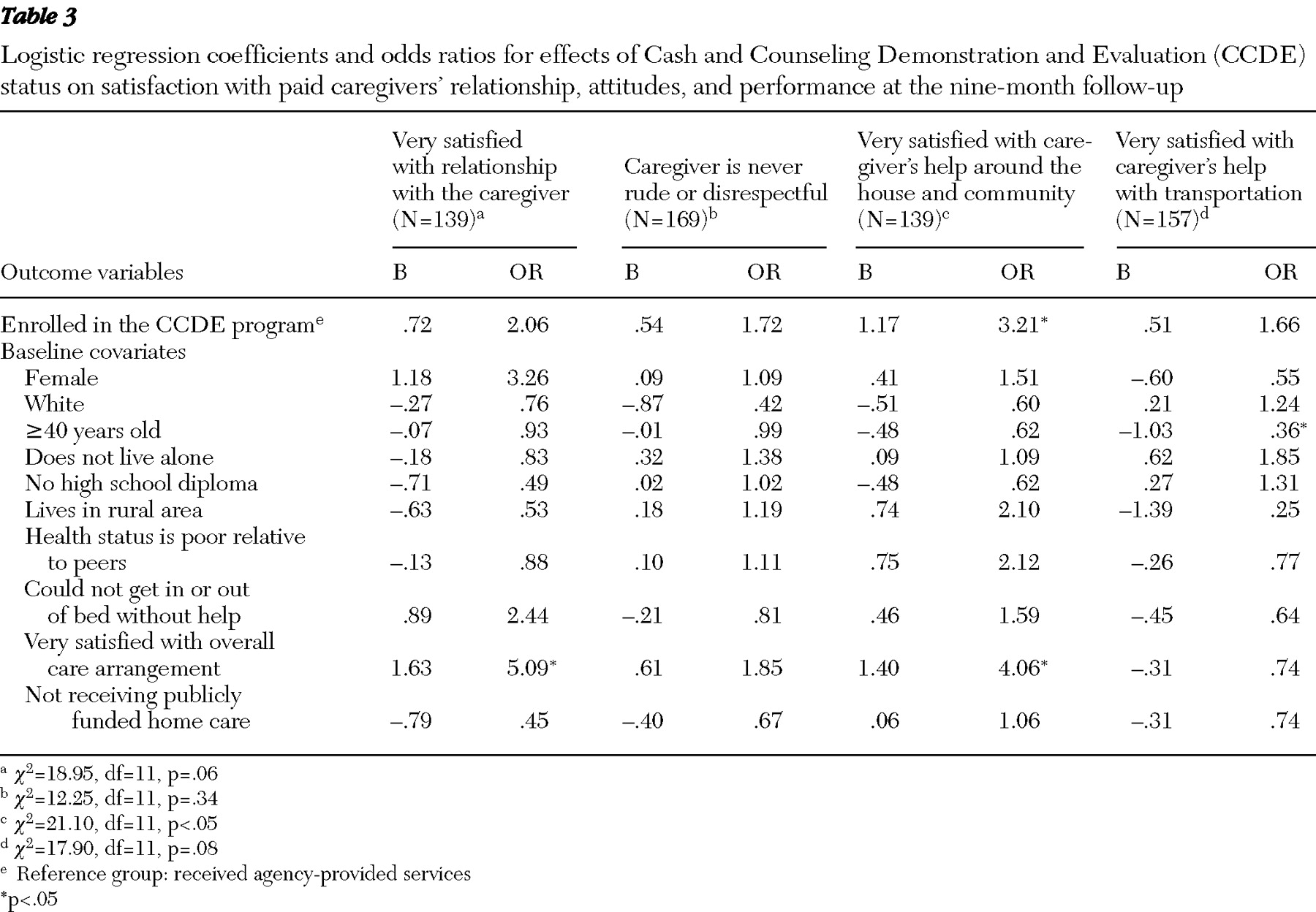

Table 3 details outcome measures reflecting consumers' satisfaction with their relationship with the caregiver, perception of their caregivers' attitudes, and two measures of their perception of their caregivers' service performance. As shown in

Table 3, all of the four outcomes demonstrate CCDE's positive effect after the analyses controlled for the effects of the baseline characteristics. However, only satisfaction with caregiver's help around the house and community was statistically significant (p<.05).

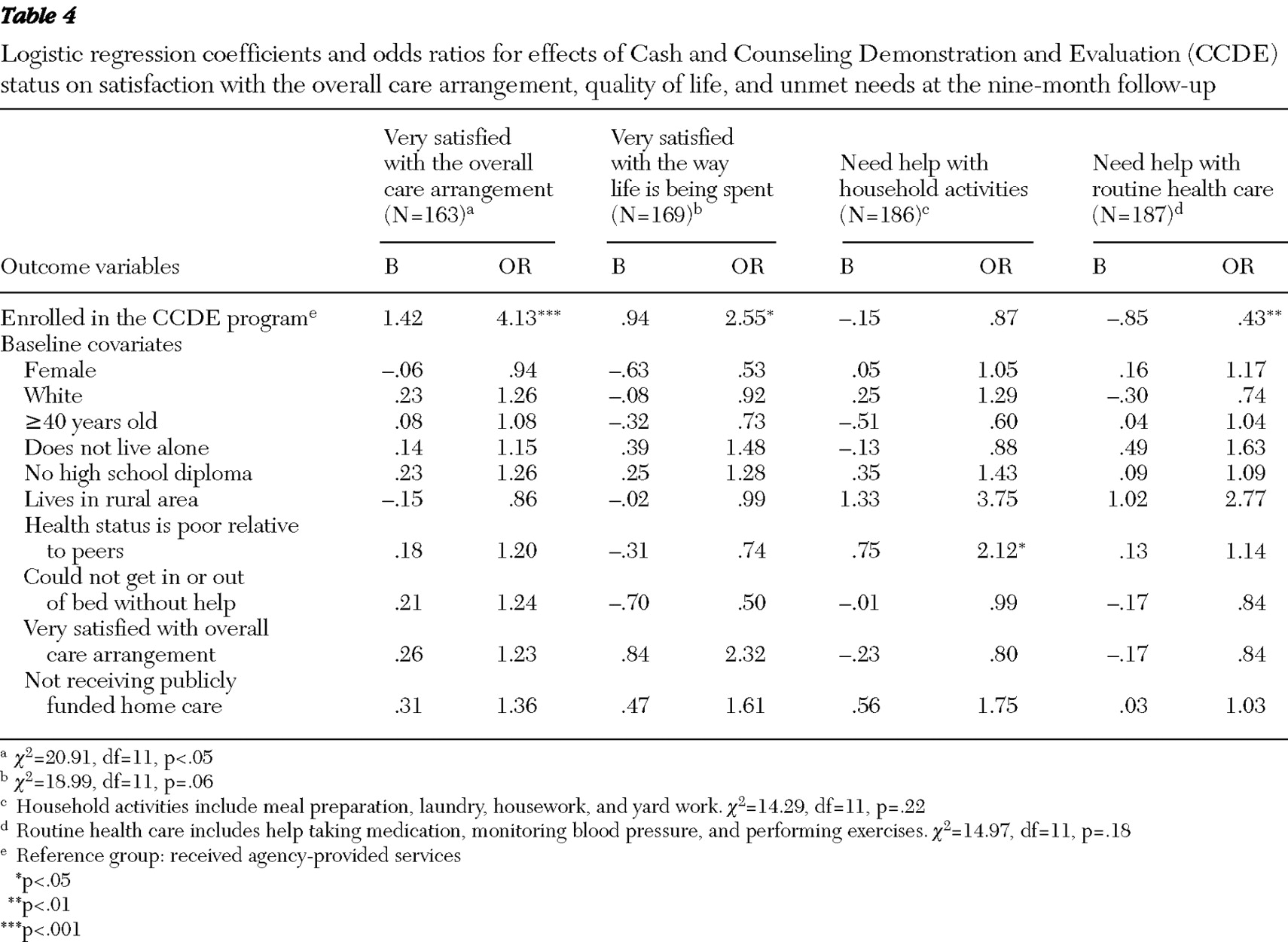

Table 4 addresses two aspects of the effects of the CCDE program—consumers' satisfaction with their overall care arrangements and satisfaction with the way they are spending life—and two measures of unmet needs. As shown in the table, after the analyses controlled for the effects of the ten baseline covariates, including "very satisfied with overall care arrangement" at baseline, the first two outcome variables demonstrate the CCDE program's significant positive effects (very satisfied with overall care arrangement [p<.001] and very satisfied with the way life is being spent [p<.05]). For the third and fourth outcome measures (unmet needs), both odds ratios are less than 1, indicating that consumers in the treatment group were less likely to claim unmet needs for help with household activities (such as meal preparation, laundry, housework, and yard work) and help with routine health care (such as help taking medications, monitoring blood pressure, and performing exercises). However, the category unmet needs for help with household activities was not statistically significant. The odds ratio of .43 for need help with routine health care indicates that consumers in the treatment group had about half the likelihood of claiming such needs, compared with those in the control group (p<.01).

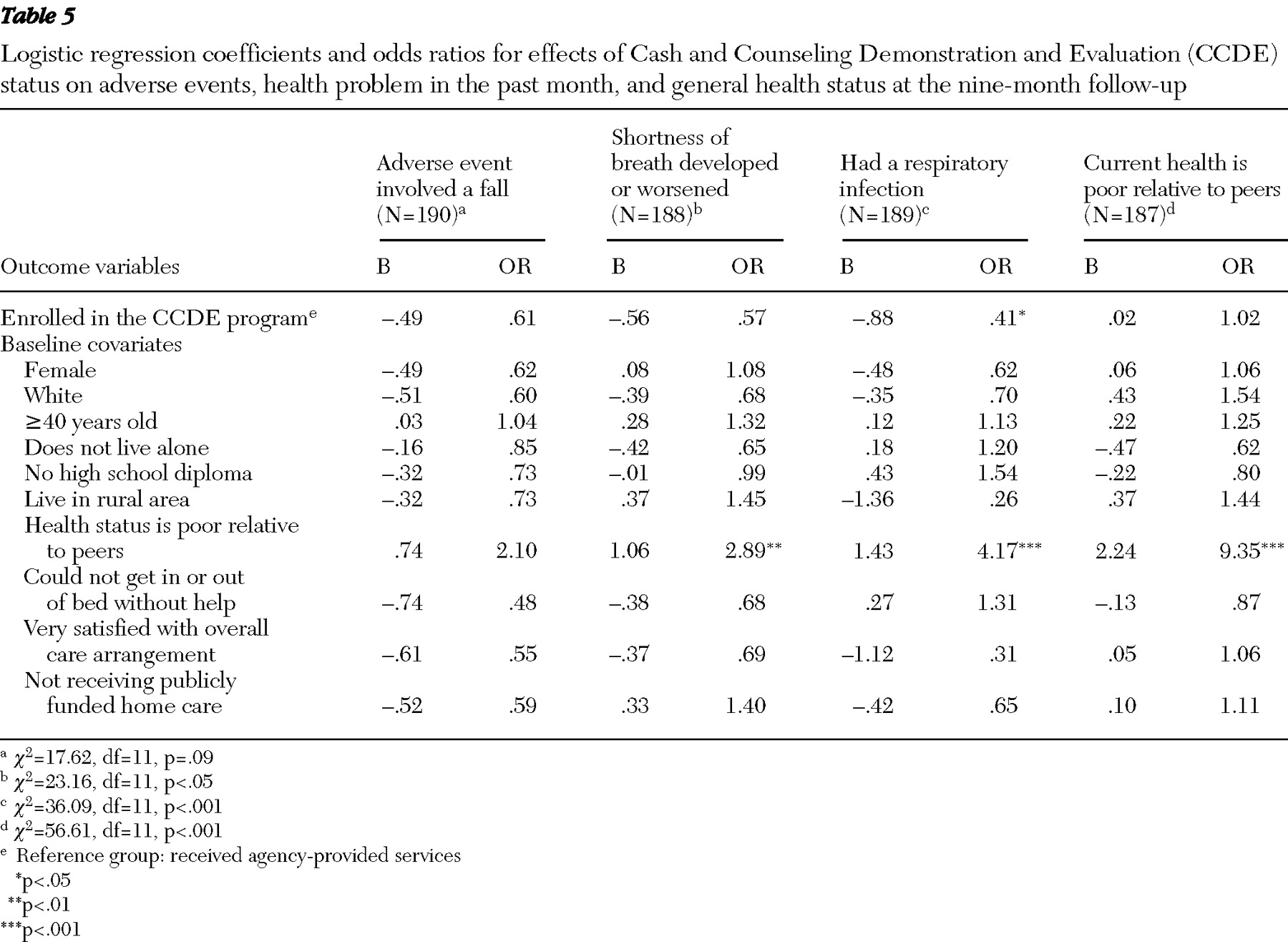

Table 5 presents CCDE's effects on issues reflecting adverse events, health problems, and general health status. MPR's original study included several measures of adverse events in the past month including "fell," "saw a doctor because of fall," and "saw a doctor due to cut, burn, or scald," and "was injured while receiving paid help." We analyzed all of these measures and found that the CCDE program had no significant effect in any model. To save space, we included just one of these adverse event measures—"fell in past month"—in

Table 5 . The odds ratio of .61 indicates that consumers in the treatment group were less likely to fall, although the difference was not statistically significant.

MPR's measures of heath problems in the past month included five variables. We report two of them in

Table 5 : "shortness of breath developed or worsened" and "had a respiratory infection." As shown, consumers in the treatment group experienced significantly less likelihood of reporting respiratory infection problems than those in the control group (p<.05). The other three measures of health problems examined but not reported here are "had a urinary tract infection," "bedsores developed or worsened," and "spent night in hospital or nursing home in past month." We found no significant differences between those in the treatment and the control groups, indicating that people in the treatment group were at least not worse off. The last outcome measure in

Table 5 is perceived general health status: "current health poor relative to peers." As shown, no significant difference between the two groups existed in our data. It is noted that those who claimed to be in poor health at baseline were more likely to make the same claim at ninth months after enrollment. Again, multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that in the CCDE program, care was at least as safe as usual treatment.

In summary, both chi square analyses and logistic analyses suggest that overall the CCDE program increased the likelihood that consumers with a diagnosis of mental illness received paid care service, better met the needs of service delivery time and reliability, increased clients' satisfaction with the overall care arrangement, increased their satisfaction with the caregivers' performance, and increased their perceived quality of life. Also, the CCDE program somewhat reduced unmet needs, and in no case did the program increase adverse events and health problems. In short, our findings are consistent with earlier findings of the CCDE program: the CCDE program worked just as well for clients with mental illnesses as for those without mental illnesses (

9 ).