Mental health reforms in the second half of the 20th century led to deinstitutionalization of care throughout Western Europe, with the closure or downsizing of large psychiatric hospitals and the establishment of alternative services in the community. Although the time of onset of reforms, their pace, the political context, and the exact objectives varied substantially across Europe, practically all countries underwent major reforms aimed at establishing services in the community to replace asylum-based care.

A study that analyzed data on service provision from six European countries showed that the number of conventional inpatient beds was still falling between 1990 and 2002 (

1 ). At the same time, however, there was a significant increase in forensic beds, in places in supervised and supported housing, and in the prison population. A substantial proportion of the prison population can be assumed to have mental disorders. Thus a new trend of "reinstitutionalization" was suggested. In the meantime, similar data have been reported for Israel (

2 ). The aim of this study was to analyze more comprehensive data from more countries and investigate whether there is a trend in Europe toward further reinstitutionalization since 2002.

Methods

We collected service provision data from Western European countries and applied the same inclusion criteria for countries that were used in the original study (

1 ). Countries were included if they had experienced major mental health care reforms involving deinstitutionalization during the second half of the 20th century and if reliable and reasonably complete data were available. The selected countries were intended to represent various European traditions of mental health care, including Scandinavian, Central European, and Mediterranean countries.

We used the same indicators of levels of mental health care institutions as in the original study: conventional psychiatric inpatient beds, which are now commonly provided in units attached to or part of general hospitals; involuntary hospital admissions, which are regarded as important in this context, although they indicate a specific activity and not an institution; forensic psychiatric inpatient beds; places in residential care and supervised and supported housing; and places in prisons. The numbers of mainstream psychiatric inpatient beds, forensic beds, and places in supervised and supported housing are seen as core indicators of levels of institutionalized care. The number of involuntary hospital admissions is provided to assess the context of compulsory treatment. The prison population is relevant to consider both the societal context and the possible number of incarcerated people with mental illness.

After extensive contacts and communication with experts in several countries, we included data from nine countries—Austria, Denmark, England, Germany, Republic of Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland. We were unable to identify reliable or sufficiently recent data in other countries, including France and Sweden.

In each country the national expert searched for primary sources of data on conventional inpatient beds, involuntary admissions, forensic beds, and places in residential care and supervised and supported housing. Because data-reporting systems vary between countries, we had to use very different types of data sources, most of which are specific and in the national language. Data on the prison population for all countries other than Switzerland were taken from the International Centre for Prison Studies (

3 ). We identified figures for 1990 (regarded by historians as the end of the postwar era in Europe), 2002 (the year on which the previous publication by our research group was based), and 2006. If reliable data for the exact years could not be established, we used different years. Because health care in several countries is regulated on a regional rather than a national level, national data could not always be obtained. In such cases we used regional data and selected the regions on the basis of their size and on the availability of data. All data were transformed into the number of provided places in the given type of service per 100,000 crude population.

Because legislation and health care systems in the nine countries vary substantially, the definitions of each category also differ considerably. This inconsistency applies more to forensic beds and involuntary hospital admissions than to conventional hospital beds and the prison population. It is most relevant for the various forms of residential care and supervised and supported housing, which range from traditional nursing homes to support provided in apartments of patients in the community (

4,

5,

6 ). However, we used identical definitions for the three time points within each country so that changes over time are based on consistent concepts and terminology.

Discussion

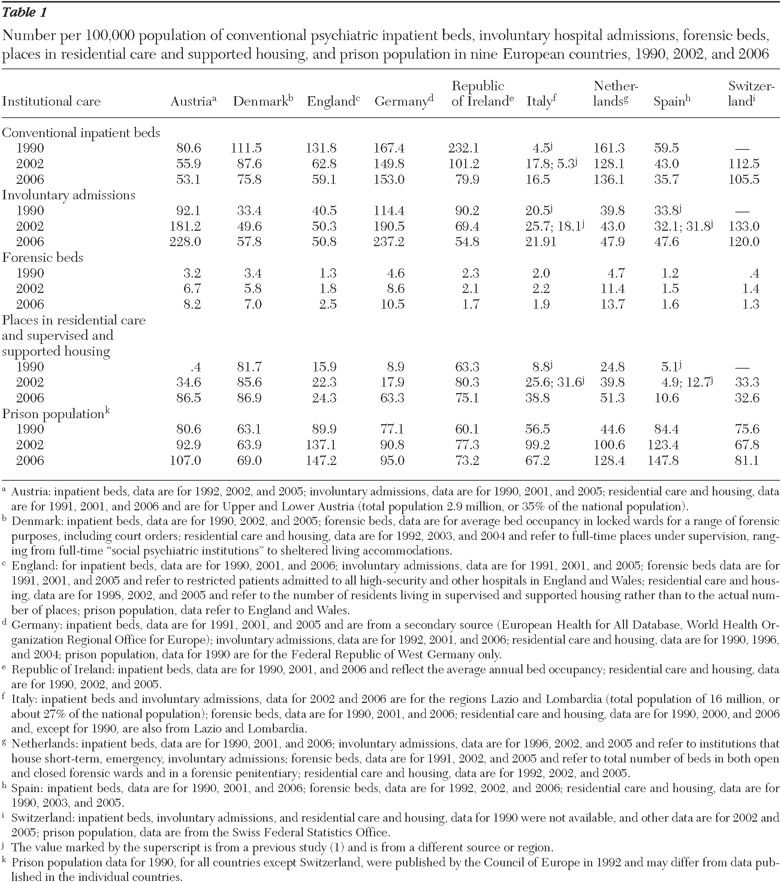

The figures in

Table 1 show an ongoing trend toward an increase in forensic beds and places in supervised and supported housing, although this finding was not consistent across all countries. The number of conventional inpatient beds further decreased in most countries, but no association was found between a reduction in conventional inpatient beds and an increase of forensic beds and places in supervised and supported housing. For instance, inpatient beds increased in Germany and the Netherlands, where there also were substantial increases in the number of forensic beds and places in supervised and supported housing. In Austria and Italy the increase in places in supervised and supported housing since 2002 overcompensated for the loss of conventional beds. At the same time, in Ireland and Switzerland conventional psychiatric beds as well as forensic beds and supervised and supported housing places were reduced. Thus additional investment in forensic beds and supervised and supported housing does not appear to be directly linked to bed closures in conventional inpatient services. Although involuntary admissions showed inconsistent changes across countries, the prison population increased sharply in seven countries. Since 2002 there was a reduction in involuntary admissions in Ireland and Italy, but the numbers are still higher than in 1990.

One limitation of the study is that it focused only on Europe and included only countries in Western Europe. We were unable to identify data for some countries of specific interest, such as France. Countries in Eastern Europe did not meet the inclusion criterion of having undergone major mental health care reforms with deinstitutionalization in the second half of the 20th century and are at a different historical stage of developing mental health care than the countries in this report.

Although largely primary sources were used, this does not necessarily guarantee the accuracy of the reported data in all cases. We established sufficiently reliable figures only for defined years with long intervals between them. Specific data for every year would have enabled a more detailed analysis of annual changes, but such data were available for an even smaller number of countries than the nine included in this study.

Reports with national data are published on the basis of various time frames, and an analysis of data from several countries has to wait until the final data to be included have been released. As a result, more recent figures may be available for some categories and countries but not for all of them. It is interesting and concerning to note how difficult it has been to collect simple data on service provision on national levels, and it might be seen as a political challenge to arrange consistent and reliable data collection across all European countries.

This analysis focused on service provision as an alternative to conventional inpatient care, which included service provision in prisons. The prison population in all studied countries has considerably increased since 1990, although the number of prison places per population is less than 20% of the number in the United States. Several studies suggest that a large proportion of prison inmates have severe mental illness (

7 ), and prisons have been termed "new asylums" (

8 ). However, exact data on the proportion of people with serious mental disorders among the prison population are not available. Thus one can only speculate about the extent to which the increased prison population includes larger numbers of people with mental disorders.

Although the absolute numbers listed for each country should be interpreted and compared only with great caution, the data suggest that not all changes across Europe are leading to greater consistency. Rather the findings indicate that countries with higher levels of forensic beds tend to increase them even more and countries with relatively large numbers of conventional inpatient beds did not—between 2002 and 2006—close down as many beds as countries with fewer beds in 2002. Germany and the Netherlands had the largest numbers of conventional beds in 2002 and increased them even further. The only tendency toward harmonization might arguably be detected with respect to places in residential care and supported housing.

Factors driving the increased provision of care in institutions remain unclear. Potential explanations, which are not mutually exclusive, include greater morbidity, which may be associated with higher levels of urbanization, changed lifestyles, and more widespread drug use. However, there is little if any research evidence demonstrating that rates of severe mental illness have risen substantially in the countries included in the study. Another possible explanation is increased risk averseness in societies in general and among clinicians in particular, which may result in more frequent decisions to refer patients to secure places. This may happen even though crime rates have not shown a large increase in Europe and there is no evidence for increased homicide rates among persons with mental illness (

9 ). A third possible explanation is a reduction in informal support in the community for people with mental illnesses, which has required institutions to step in. Fourth, a strong lobby of health care providers may have persuaded commissioners to invest in health care institutions. Fifth, there may be a tendency among health care funders to move costs for the care of severely ill people to the social care sector, which often funds residential care and supervised and supported housing, or to the justice system, which funds prisons.

Whatever the explanation, one may assume that common factors are facilitating reinstitutionalization in various European countries. At the same time the trend does not appear inevitable, because three countries with distinct traditions and different economic constellations—Ireland, Italy, and Switzerland—have shown changes in the direction of less institutionalized care. Ireland has reduced all forms of care institutions considerably since 2002, and the same holds true for Italy, with the exception of places in supervised and supported housing, and for Switzerland, with the exception of the prison population. The similarities across Europe may merit as much further research as the differences in order to understand specific factors that drive changes in the provision of institutionalized mental health care.

With respect to the number of psychiatric hospital beds, a recent analysis of time series from the 19th and 20th centuries in Italy, England, and the United States has suggested macroeconomic factors as a main driver for more investments in hospital beds or reductions in their numbers (

10 ). Similar analyses would be welcome for new forms of institutionalized care, but they require series of reliable data, which cannot be obtained for most countries, especially for the crucial categories of residential care and supervised and supported housing.

Conclusions

The findings underline the need for a debate on the direction of care for people with severe mental illnesses. Institutions as such are neither good nor bad, but they always absorb funding. Care institutions are expensive, and there is limited evidence of their effectiveness. Although the therapeutic value of forensic beds requires further evaluation, there is wide consensus that prisons commonly do not provide the most helpful environment for people with mental illnesses. With respect to residential care and supervised and supported housing, services can range from unacceptable, which has been called the "return of the private madhouse," to comfortable and protective settings with little incentive for patients to move to more independent living, which have been referred to as "golden cages" (

11 ). Quality standards for supervised and supported housing services are often low and poorly defined, with limited incentives for provider organizations to help patients move to more independent forms of living. National policies should aim to develop and implement precise standards, so that all patients living in such service settings receive acceptable care, including consistent appropriate rehabilitation.

All care institutions tend to compromise the autonomy of patients, which in the spirit of deinstitutionalization and patient empowerment should be done only if there is no less protective alternative. The mental health care field needs both a debate on the values of care and good research on the effects of different forms of institutionalized care.