Bipolar disorder is a severe and recurrent mental disorder that is the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide among people 15–44 years of age. It is associated with a greater degree of disability than several prominent chronic medical conditions, including osteoarthritis, HIV infection, diabetes, and asthma (

1 ). There is growing consensus that one of the most difficult and pervasive obstacles to good outcomes among persons with serious mental illness, including those with bipolar disorder, is the individual's discontinuation of medications (

2,

3,

4 ). Studies evaluating the extent of nonadherence among bipolar populations report that approximately 20%–70% of patients are poorly adherent with medications (

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9 ).

Medication adherence in bipolar populations is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by a number of illness, patient, provider, and system factors (

5,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15 ). Age, gender, psychosocial supports, symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, medication-related adverse effects, and attitudes toward medication and treatment have all been associated with adherence status (

9 ). Models of health behaviors that focus on determinants of adherence note the importance of personal illness attribution and understanding the effect of experience on an individual's health beliefs. These include perceptions of susceptibility to illness, perceived severity of illness, the benefits of treatment, the costs and burdens of treatment, and cues to action that may promote treatment adherence (

9,

16,

17,

18,

19 ). Individuals with bipolar disorder face various barriers that may compromise treatment adherence, including difficulties in understanding and remembering complex medication regimens, side effects from medications, issues of treatment cost and access, difficulties in navigating an often complicated health care system, and stigma related to having mental illness and requiring treatment (

9 ). Identification of potentially modifiable factors that predict treatment adherence is critical in order to develop effective interventions for adherence enhancement in bipolar populations.

A cross-sectional analysis of factors associated with treatment nonadherence in a bipolar veteran population suggested that current substance abuse, disability status, and number of irregular hospital discharges were more common among veterans who were nonadherent compared with those who were adherent (

20 ). Although there is a fairly substantial body of data regarding cross-sectional adherence prevalence and predictors in seriously mentally ill populations, prospective and longitudinal adherence data are much more limited (

21,

22 ), and the longitudinal adherence data available are primarily from populations with schizophrenia (

21,

23 ). However, factors that are associated with nonadherence over time may be of particular importance with respect to identifying individuals who might be at greatest risk of nonadherence and may aid in the development of future interventions that could enhance treatment adherence in these high-risk groups.

This secondary longitudinal analysis of self-reported treatment adherence is part of a larger study involving veterans with bipolar disorder participating in a randomized, multicenter research trial (

24,

25 ) and follows our baseline assessment of the same sample (

20 ). The aim of this secondary analysis from a larger study was to identify the association between baseline variables and average treatment adherence over a subsequent three-year period. We hypothesized that veterans with no current substance abuse, those on disability, and those on more intensive medication regimens would be more adherent with bipolar medication treatments over time compared with bipolar individuals who are nonadherent.

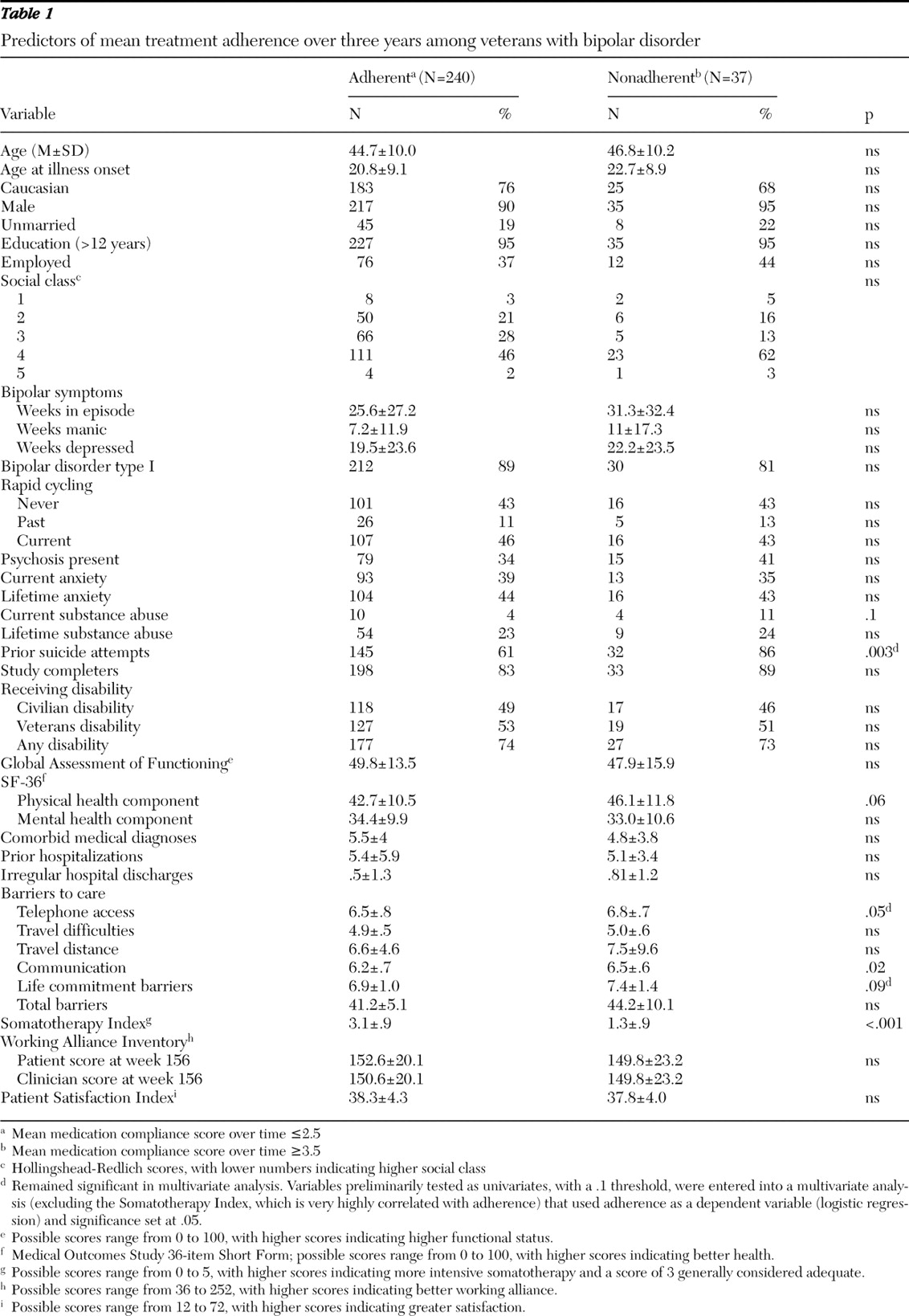

Discussion

This prospective study, in which we examined the relationship of baseline variables to average adherence to medication during a subsequent three-year period in a bipolar population, found that nonadherence was relatively common (just over 12%). This finding is somewhat lower than the nonadherence rates of 20%–35% reported in some randomized controlled trials conducted with patients with bipolar disorder (

39,

40,

41 ). The difference may be related to the longer duration of this study and the fact that average adherence over all three years served as the dependent variable. There has been some concern regarding the relevance of patient outcomes from a randomized controlled trial to real-world clinical practice (

42 ). Accordingly this study provided clinically relevant new information because it was designed from the outset as an effectiveness trial (

26 ). The study sample comprised individuals with multiple psychiatric and medical comorbidities. In comparison with other large samples of patients with bipolar disorder, those in our sample were somewhat older, were more severely ill, and had highly complex symptoms (

24,

25 ). In relation to the overall veteran population, our sample had a larger proportion of women and persons of racial-ethnic minority groups (

26 ). Participants in this study also had relatively high rates of hospitalization, prior suicide attempts, and disability.

Reasons for nonadherence among bipolar populations are multiple and diverse (

43 ), and reports of treatment nonadherence in the general population of patients with bipolar disorder are in the order of 20%–55%, (

13,

44,

45,

46 ), with levels approaching 55% in longitudinal adherence studies (

47 ). In the study reported here, nonadherence was associated with lower-intensity bipolar medication treatment, more barriers to care, and more previous suicide attempts. Demographic and clinical variables, such as age, gender, ethnicity, symptom severity, comorbid substance abuse or anxiety, functional disability status, and general health status, were not different between nonadherent and adherent groups. It is possible that lower-intensity medication treatments by nonadherent individuals may thus reflect difficulties with access to care, at least in part, rather than differences in symptoms or functional status.

A previous cross-sectional, baseline analysis of treatment adherence in this same clinical trial population (

20 ) found that nonadherence by individuals with bipolar disorder was associated with current substance abuse, being on disability status, receiving less intense bipolar medication treatments, and having a history of irregular hospital discharges. It is possible that participation in the longitudinal clinical trial presented here may have diminished some of the effects of substance abuse (or substance use intensity) on individuals participating in this study.

Other investigators have identified a relationship between nonadherence and suicide in bipolar populations (

48,

49 ). Baldessarini and colleagues (

49 ) reported that suicidal acts were reduced 6.5-fold per year during lithium treatment of bipolar disorder and that suicide rates rose 20-fold in the first year after ceasing use of lithium. It is possible that in the population presented here, previous suicide attempts could have been related to long-standing nonadherence with medication treatments. Given the previous pattern of attempts at self-harm among bipolar patients, the apparent lack of biologic treatments known to be effective for bipolar disorder is particularly worrisome, and nonadherent individuals with bipolar illness likely represent a group that could be particularly vulnerable to future suicide attempts.

Our findings of increased selected barriers to care among nonadherent bipolar patients suggest that problems with access to care may explain, at least in part, the reduced utilization of medication treatments. This explanation is consistent with our prior proposal that nonadherence can be best understood as a function not of the patient in isolation but rather as part of a complex system that includes both the provider and the health care organization (

20 ). McCarthy and colleagues (

50 ) examined a VA population with serious mental illness and noted that geographic accessibility to care and resource availability were associated with long-term continuity of care and that, conversely, increased distance from providers was associated with greater gaps in health care use. The greater number of barriers to care among nonadherent individuals with bipolar illness in the study presented here may provide a clue about measures that may enhance adherence in historically nonadherent populations. Findings of this analysis suggest that barriers to access of care, particularly barriers to telephone access, are a reasonable starting place to study further and potentially design future interventions. McCarthy and colleagues (

51 ) have suggested that patients with bipolar disorder and receiving care in the VA may reduce accessibility barriers by "chaining" or coordinating multiple outpatient visits within a single visit to the VA service center. Similarly, pooling of access services for diverse types of health care within one or more networks could lead to reduction in communication or telephone barriers to care.

Previous data on longer-term predictors of nonadherence in mood- disordered populations (

9,

47 ) suggest that negative attitudes toward mood-stabilizing medication prophylaxis are a strong correlate of nonadherence to lithium therapy. Although the study presented here did not specifically evaluate attitudes toward long-term medication prophylaxis, it is possible that the relatively low utilization of medication could also be associated with lack of interest in medication prophylaxis in addition to perceived barriers to care. Relationship with providers (working alliance) did not appear to differ between adherent and nonadherent patients in the sample we studied, so any attitudinal differences may have been centered on biologic treatments. The greater number of previous suicide attempts among nonadherent patients suggests that these individuals are possibly more ill overall compared with adherent individuals.

Limitations of this study include the utilization of a sample treated solely within the VA health care system, underrepresentation of women, self-report-based method of adherence assessment, and the inclusion of only participants who agreed to participate in a research study. Although Stephenson and colleagues (

52 ) have suggested that self-report may overestimate adherence rates by about 15%, it is interesting to note that self-report in bipolar disorder appears much more reliable than clinician predictions, which have only 50%–60% accuracy (

19 ). The nonadherent individuals in this study do not represent the most extreme end of the nonadherence spectrum, because those at the most extreme end would likely not agree to participate in a clinical trial.

There were additional limitations. Even though the study retention rate of over 80% over a three-year period is quite good for longer-term bipolar studies, it was not possible to follow adherence status and possible clinical associations for the study population that did not complete the protocol. It must be noted that given the paucity of data on longitudinal adherence predictors in populations with bipolar disorder, the statistical methods used to preliminarily identify positive long-term predictors are exploratory and data should be interpreted with caution. Because multiple comparisons were made in this study it is possible that study findings could be by chance alone. Predictors for long-term adherence need to be confirmed with future studies using a more rigorous design and specific hypothesis testing. Finally, medication and resource use patterns in the VA may differ from those seen in a noncentralized care system, where there may be other restrictions to various health care services, including medications. It is possible that in noncentralized systems, barriers to care may be even more strongly associated with treatment nonadherence.