Bipolar disorder gives rise to significant disability and expense, which result from medication costs, psychiatric hospitalization, and time lost from work. Even though the prevalence of bipolar disorder is roughly 17% that of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder has an associated aggregate economic burden that is more than twice that of major depressive disorder (

1 ). Such data suggest that bipolar disorder has a disproportionate impact on health care costs and service use.

Psychiatric hospitalization in bipolar disorder can occur during manic or depressed phases of the disorder. In a study of 6,072 patients diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, 9% were hospitalized in a year, which accounted for 11% of the health care costs of the sample (

2 ). Despite the importance of psychiatric hospitalization, little work has been done to determine what factors are most closely associated with psychiatric hospitalization of patients with bipolar disorder. The first study of risk factors for psychiatric hospitalization found that patients presenting with severe neurovegetative or manic symptoms were more likely than those without such symptoms to be rehospitalized within six months (

3 ). Epidemiological studies have revealed that patients with bipolar disorder and comorbid alcohol abuse have more psychiatric hospitalizations, compared with those with bipolar disorder alone (

4,

5 ), and patients with substance use disorders have a higher prevalence of work-related disability (

6 ). There is additional evidence that cannabis use is associated with an increased amount of time spent in affective episodes (

7 ). Similarly, the diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder was the strongest risk factor for psychiatric hospitalization among older patients with dementia and comorbid bipolar disorder (

8 ).

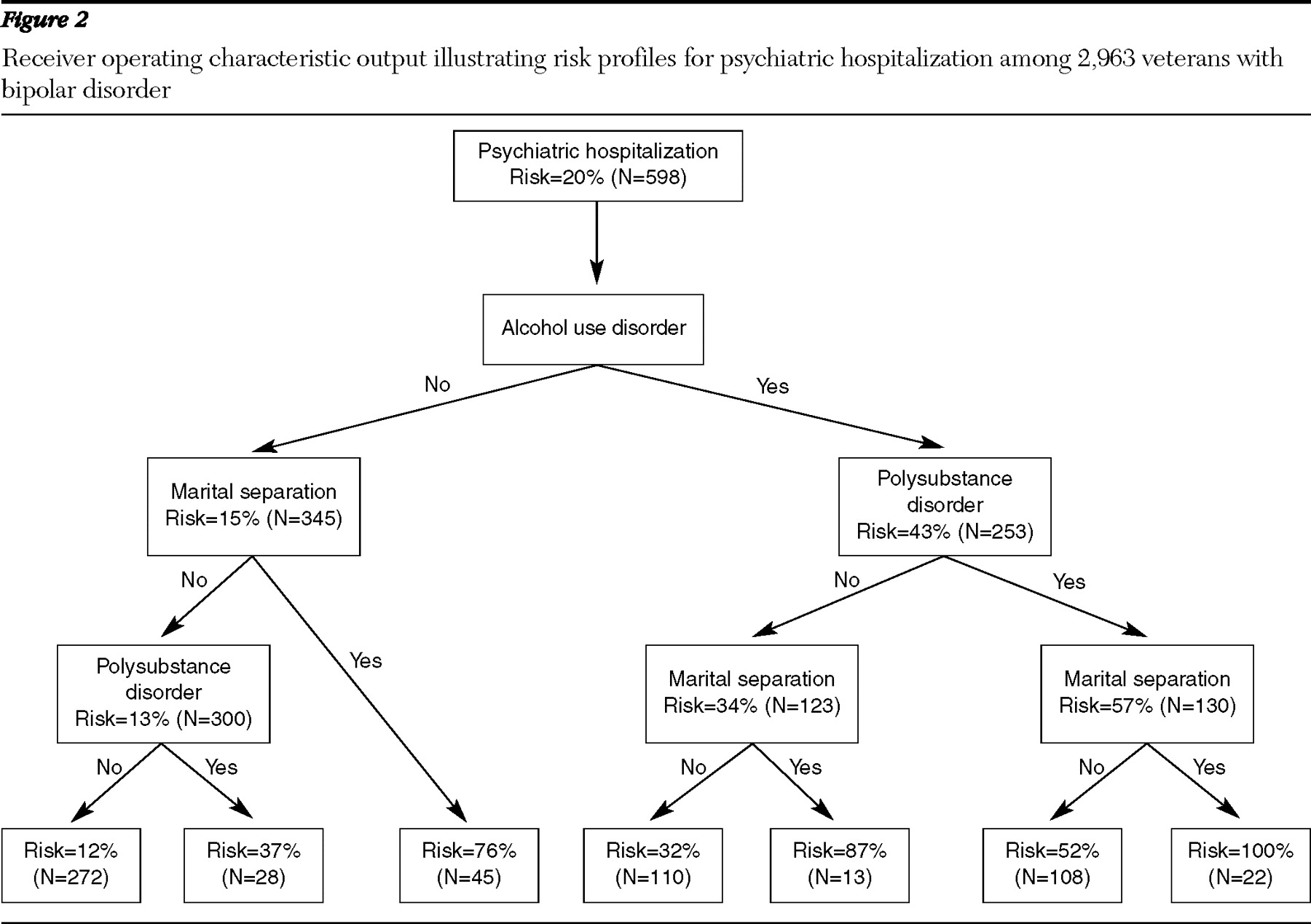

Although there are reports of associations between rehospitalization rates and substance use disorders, there are no clinical profiles that could be used to assess a patient's risk of psychiatric hospitalization or determine the relative importance of various risk factors. Risk profiles can provide information about the interaction of different clinical and demographic characteristics that are associated with psychiatric hospitalization, which in turn give clinicians predictive information and suggest areas of focus for additional treatment. In the study presented here, we used the aggregate administrative Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System database to gather clinical information on all patients diagnosed as having bipolar disorder during a one-year period. We then used an iterative receiver operating characteristic (ROC) (

9 ) approach to develop risk profiles of psychiatric hospitalization based on comorbid diagnoses of substance abuse or dependence and other demographic characteristics.

Methods

Database

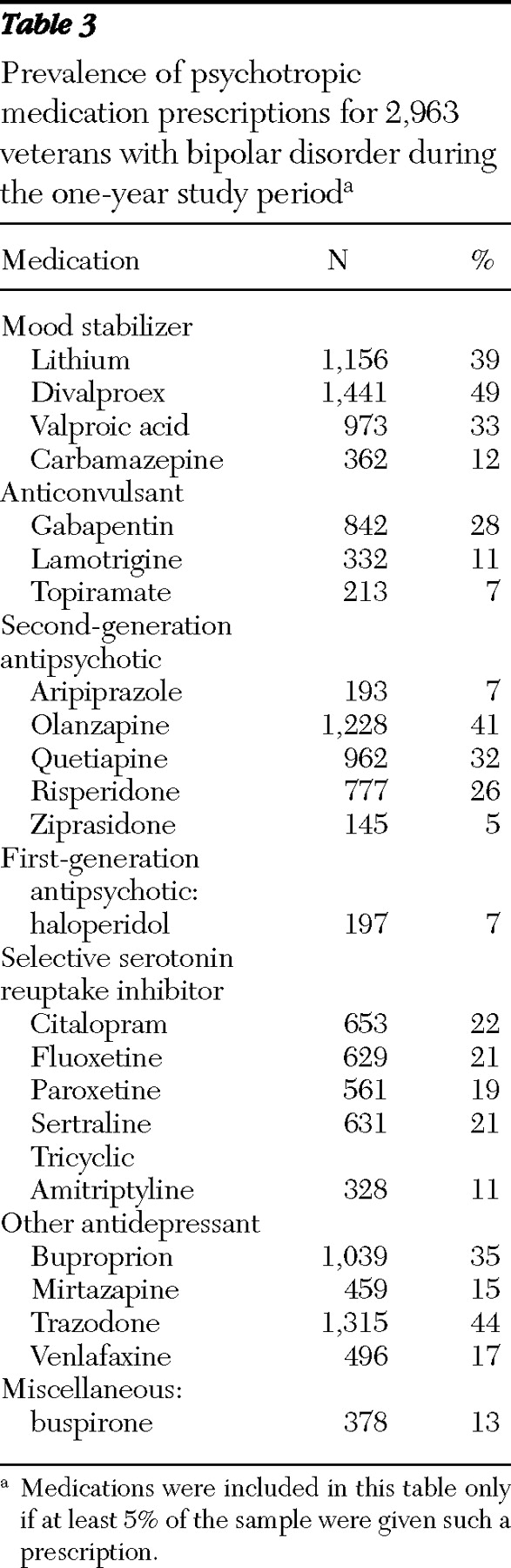

The primary criterion for inclusion in our data set was a diagnosis of bipolar disorder I, II, or not otherwise specified ( ICD-9 codes 296.0 and 296.4–296.8) from the VA Veterans Integrated Service Network 21. Patients were included in the sample if the diagnosis of bipolar disorder was present in their problem lists as a primary or secondary diagnosis during the 2004 fiscal year (October 1, 2003, through September 30, 2004). The possible predictors used in this retrospective study were coded at both outpatient and inpatient encounters during the entire study period. The VA uses comprehensive assessment tools in both the outpatient and inpatient environments in combination with annual mandated reviews of alcohol and drug use, including nicotine. Of the 2,963 patients in the sample, 2,553 (86%) were male and 410 (14%) were female. The mean±SD age was 52.9±12.3 years. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Statistical analyses

An iterative ROC analysis (

9 ) was performed with software available in the public domain (

www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/roc.html ). In an ROC analysis, the event to be predicted, or the "gold standard," is identified and the ROC software is used to identify the best initial predictor. The data set is split into subgroups at a cutoff point identified by the analysis. Within each subgroup, the remaining variables are searched for the next-best predictor. Each time the "best" predictor is found, a chi square test is performed, and the variable is retained as a predictor if p<.01. The process of searching for predictors continues until the predictor is not significant or until there are fewer than ten observations in a subgroup.

In the first ROC analysis, the gold standard was whether a patient experienced at least one psychiatric hospitalization during the year. Potential risk factors for hospitalization (that is, variables chosen for consideration) included marital status (never married, married, divorced, separated, widowed, or unknown); gender; age (categorized as <40, 40–49, 50–59, or ≥60 years); alcohol dependence, abuse, or intoxication ( ICD-9 codes 303.0, 303.9, or 305.0); opioid dependence or abuse (304.0 or 305.5); cannabis dependence or abuse (304.3 or 305.2); cocaine dependence or abuse (304.2 or 305.6); amphetamine dependence or abuse (304.4 or 305.7); sedative or hypnotic dependence or abuse (304.1 or 305.4); or polysubstance dependence (304.8). We did not include ethnicity in the analysis because of a large amount of missing data; responses regarding ethnicity are voluntary in this database, and fewer than half of the patients had provided the information. Data regarding patients' income were not available. We did not use recency of military conflict as predictive variables in the analysis presented here, because it is largely confounded with age and because only 1.4% (N=41) of these patients were from the recent Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts.

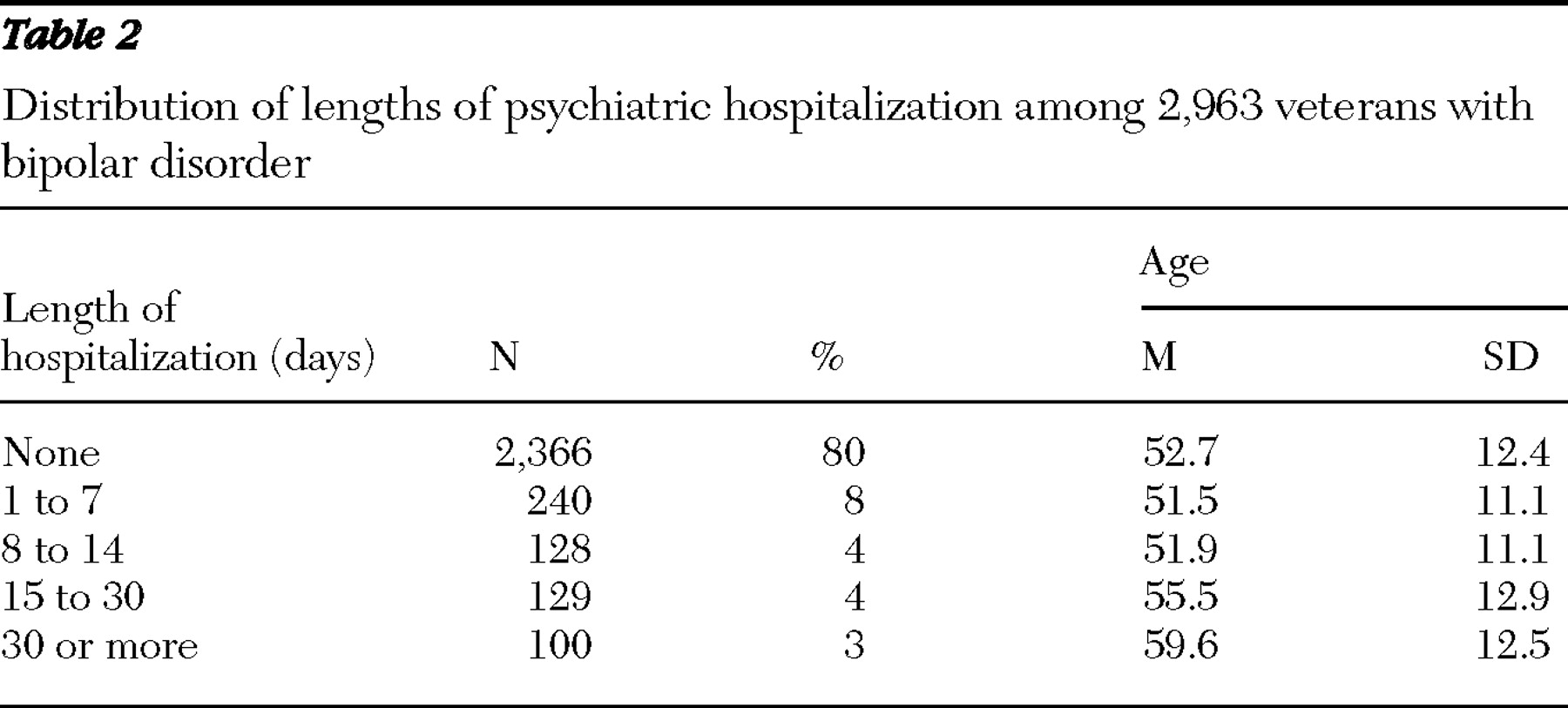

In the second ROC analysis, we used data from only the 598 patients (20%) who were hospitalized during the study period to create risk profiles for length of hospitalization. In this analysis, the gold standard was whether the length of stay was short (≤14 days) or long (<14 days). We selected 14 days as the demarcation because it represents a target length of stay for inpatient psychiatry within the VA hospital system. The second ROC analysis used the same set of risk factors as the first analysis, except that actual ages were used, as opposed to the four categories, in an effort to identify specific age cutoff points. The VA Health Care System has a variety of substance abuse treatment programs available that have typical lengths of stay from 30 to 60 days; these were not included in any of our analyses, because they do not represent acute psychiatric hospitalization.

Discussion

Substance use in bipolar disorder is associated with nonadherence to treatment (

10 ) and worse prognosis (

11 ). Comorbid substance use disorders triple the risk of suicide among patients with bipolar disorder (

12 ) and reduce medication adherence (

13 ). Longitudinal studies have revealed an increased association with depressed or mixed episodes (

14 ). Moreover, patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and substance use disorders generally experience delayed recovery from their mood episodes (

15 ). Comorbid alcohol use disorders increase the rates of both disability and mortality among patients with bipolar disorder (

16 ). Interestingly, patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and substance use disorders have generally been found to have an earlier onset of bipolar disorder than those without a coexisting substance use disorder (

5,

17 ), although this finding is not universal (

18 ).

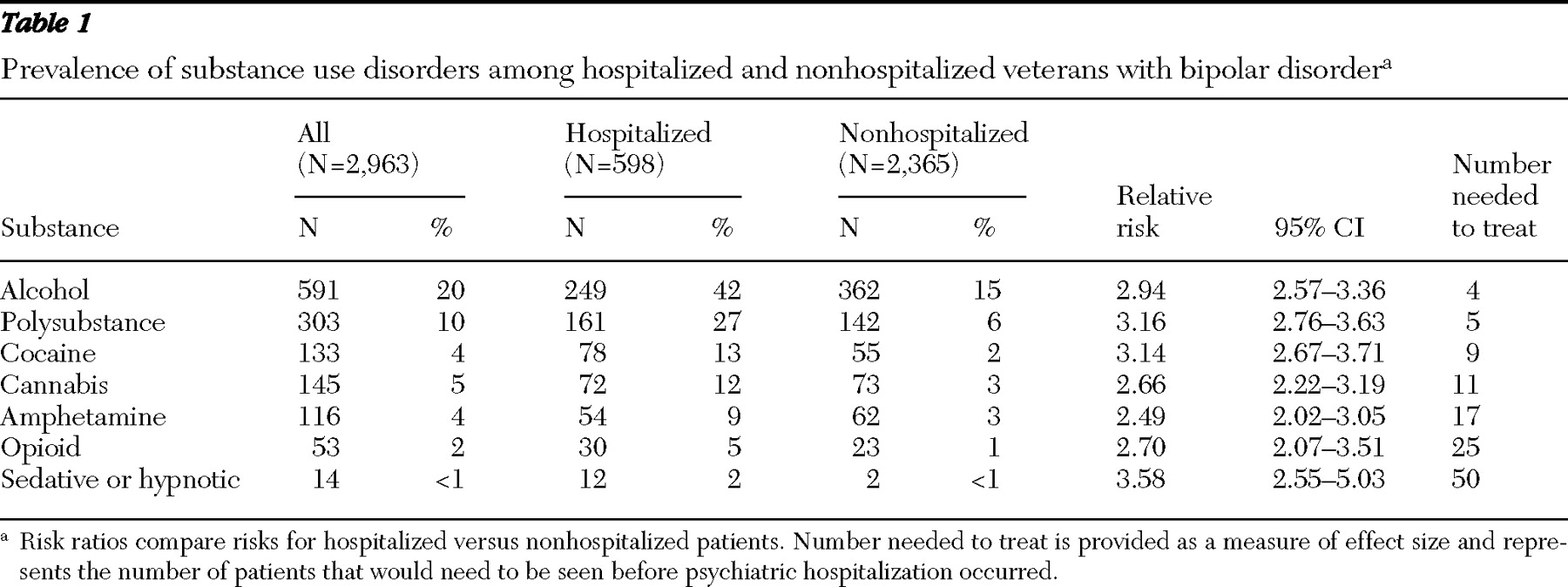

Despite the importance of alcohol use disorders and polysubstance dependence as risk factors for hospitalization, the prevalence of these disorders in our sample was somewhat lower than that reported in other samples. For example, in our study alcohol use disorders and polysubstance dependence had a prevalence of 20% and 10%, respectively. However, other researchers have reported a prevalence of substance use disorders of up to 40% of patients with bipolar disorder as soon as two years after diagnosis (

14 ) and up to 60% over their lifetimes (

11 ). The rates reported in this study are lower than those reported in other epidemiologic studies of substance use comorbidity, such as the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Regier and colleagues (

19 ) reported rates of alcohol dependence and drug abuse or dependence, respectively, for 32% and 61% of persons with bipolar disorder. It is important to note that psychiatric hospitalization is not synonymous with relapse of alcohol or drug use. It is unclear why the frequencies of substance use in our study were lower than those previously reported. One possibility is that during our one-year study clinicians may have assigned substance use diagnoses only for those with active substance abuse or dependence or that the average age of our sample was older than those in broader, epidemiological studies.

There are several important psychosocial implications highlighted by these results. Among patients with bipolar disorder but no diagnosis of comorbid alcohol or drug dependence, the strongest predictor of hospitalization was marital separation. Cannabis use disorders were not associated with the risk of hospitalization per se, although they were associated with length of hospital stay. It has been reported that patients with bipolar disorder and comorbid cannabis use disorders spend longer periods in affective episodes, compared with those without cannabis use disorders (

7 ).

Our findings suggest several possible interventions for persons with bipolar disorder that may decrease the impact of comorbid substance use disorders on health care use. An important focus of psychosocial interventions is on interpersonal relationships, and interventions have been reported to improve functioning among patients with bipolar disorder (

20 ). Recent work has also suggested that patients with bipolar disorder and comorbid substance use disorders are more likely to engage in psychosocial interventions, compared with patients with bipolar disorder but no comorbid substance use disorders (

20 ). There is a significant association between marital difficulties, without gender differences, and the onset of mania (

21,

22 ), although women with bipolar disorder are more likely than men with this disorder to be arrested for substance-related charges (

23 ). Studies have suggested that substance use can cause increased amounts of role conflicts and hence cause increased amounts of relationship distress (

24 ).

Attention to and the treatment of comorbid alcohol and drug dependence should be a priority in the care of patients with bipolar disorder (

25 ). A review of treatments for patients with severe mental illness and comorbid substance use disorders concluded that mental health treatment combined with substance abuse treatment is more effective than treatment occurring alone for either disorder or occurring concurrently without articulation between treatments (

26 ). An example of an effective combined treatment approach is the integrated dual diagnosis treatment model, which integrates treatments for mental illness and substance use disorders (

27 ). Programs that follow the integrated dual diagnosis treatment model are integrated with multidisciplinary treatment teams, are comprehensive in their use of psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions, encompass various modalities ranging from individual to family counseling, and may be offered in a long-term format (

27 ). Such substance abuse programs are a valuable part of individualized mental health care. By actively referring patients with bipolar disorder and a comorbid substance use disorder to dual diagnosis programs, clinicians may be able to significantly alter the course of one or both psychiatric conditions, resulting in lower health care costs (

28 ).

There are some limitations of our study. The VA patient population is mostly male and may not be representative of the broader population of individuals with bipolar disorder. Our study population may also differ with regard to an increased prevalence of both service-related stressors and posttraumatic stress disorder, because the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder as a primary or secondary diagnostic code in this study population was 21%. Because the diagnoses used in this study were given at clinics and during inpatient visits, they may lack the accuracy of those determined by standardized diagnostic instruments. Furthermore, the diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence may have been underestimated, because past diagnoses or disorders in remission may not have been recorded. The VA database may not capture all the health resource data, particularly for those whose disability is not service connected and who receive limited VA benefits and may thus seek service elsewhere, although only 24% of the individuals in this database had non-service-connected disabilities.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that alcohol use disorders are a major risk factor for psychiatric hospitalization and are further compounded by polysubstance dependence and marital separation. In fact, when all three of these factors were present, the risk of hospitalization in our sample was 100%. In contrast, patients without a substance use disorder who were not separated from their spouse or partner had only a 12% risk of hospitalization over the study year. Our findings stress the importance of addressing substance abuse issues and psychosocial difficulties as a means of improving patients' clinical status to avoid psychiatric hospitalization.

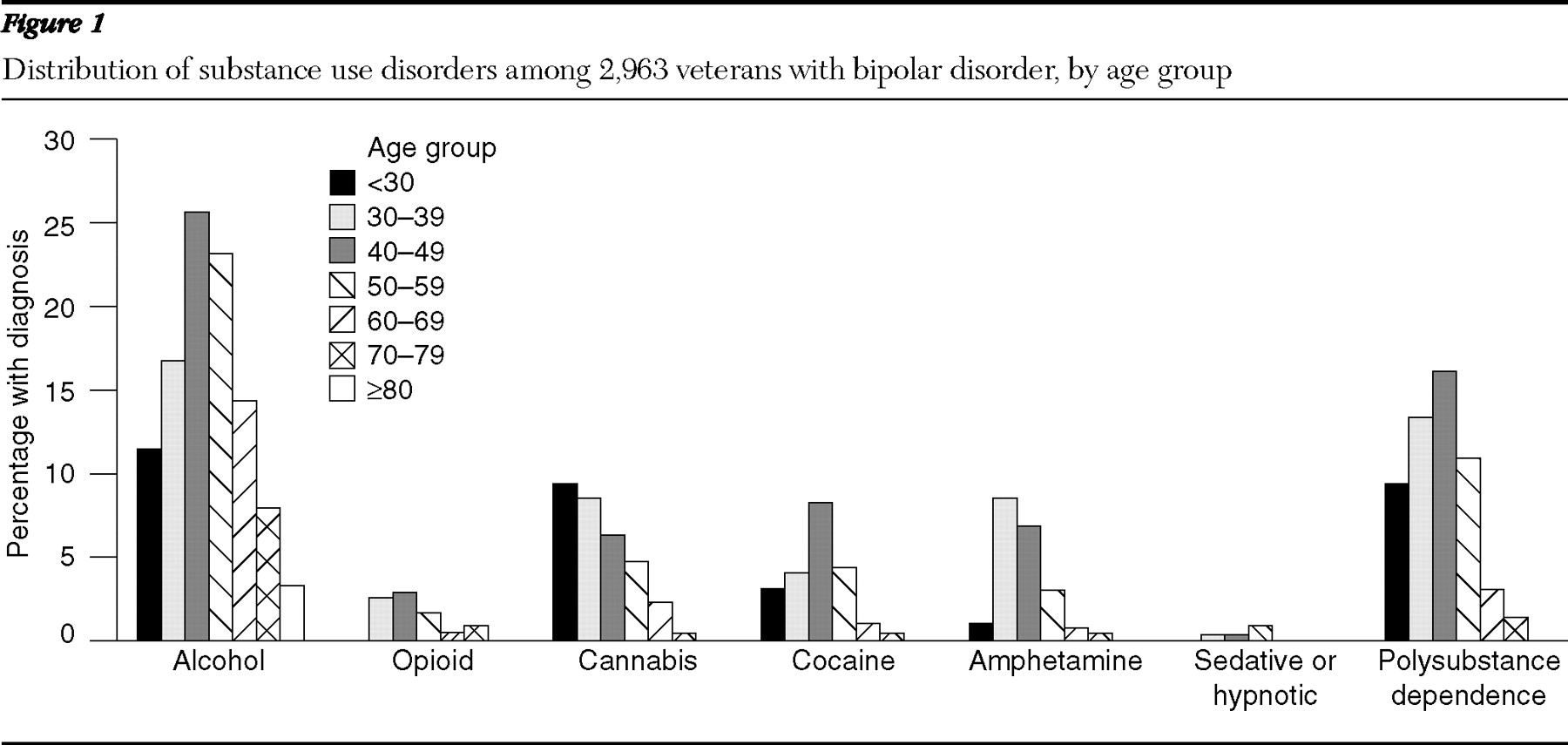

In keeping with previous findings that the prevalence of substance use disorders decreases with age (

10,

11 ), our findings demonstrated a decrease after age 50. Alcohol use disorders were more prevalent than other substance use disorders in our sample for all age ranges. Despite the trend toward lower prevalence of substance use disorders among older adults, some researchers have cautioned that as the baby-boomer generation ages, the prevalence of substance use disorders will increase among older adults (

29 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by the Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness, Research, Education, and Clinical Center.

Dr. Hoblyn is on the speakers bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eli Lilly. Dr. Brooks is on the speakers bureau for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AstraZeneca. The other authors report no competing interests.