Several studies have shown that suicide and mental illness are closely linked (

1 ). Psychiatric patients are a priority group in several national suicide prevention strategies in various countries (

2,

3 ), but only a small number of studies have examined the clinical care that psychiatric patients received before their suicide. Audits in the United Kingdom (

4 ) and Australia (

5 ) found several treatment-based risk factors for suicide among users of mental health services, including inadequate assessment and treatment of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial problems, problems with inpatient observation, and poor continuity of care. About 20% of the suicides of these mental health service users were considered to be preventable.

The Netherlands is one of the few European countries with a continuous national supervision and audit procedure for suicides of patients receiving mental health care. The system has been in operation since 1984. Whenever such a suicide occurs, the therapist responsible for the patient and the medical director must write a notification to the Health Care Inspectorate, which is an independent organization under the Minister of Health, Welfare, and Sport.

The notification must include details of the suicide and the mental health care delivered and an evaluation of policies in place for dealing with suicidal patients. The inspector may ask for more information and in some cases may require the health care service to improve the care that is offered to suicidal patients. In general, the aim of this procedure is not to evaluate individual suicide notifications but to identify structural problems in mental health care services. Some 550 suicide notifications are submitted per year, which account for 36% of all suicides annually in the Netherlands.

The supervision system of the Health Care Inspectorate is designed to improve the quality of care for suicidal patients and ultimately to prevent suicide. However, its effectiveness has never been evaluated. The study presented here is a preliminary step in this evaluation. The aim was to describe the management of suicide notifications by the inspectorate and to compare its responses with recent guidelines for suicide prevention (

6 ) to determine whether supervision could be improved. In addition, changes in the manner in which the inspectorate has responded to suicide notifications over time was examined. The results will be used in further studies to assess the impact of the inspectorate's supervision.

Methods

Suicide files were made available by the Health Care Inspectorate for the period 1996–2006. All suicide notifications from this period were identified (N=5,483), and a total of 505 were selected. For 1996–2000, a total of 100 notifications were selected, and 200 were selected for 2001–2005. For 2006 the first 205 suicide notifications submitted that year were obtained. A relatively large number of cases from recent years were examined, because these were considered to be most representative of the current procedures of the inspectorate. Files from earlier years were studied to gain insight into historical developments in the management of suicide notifications.

For 1996–2005 an equal number of suicide notifications with and without a response from the inspectorate were randomly selected. A response was defined as further questions, remarks, or suggestions by the inspector after the initial notification or a personal conversation between the inspector and the person who sent the notification. No follow-up was defined as a simple letter from the inspectorate acknowledging receipt of the notification with no further questions or remarks. A total of 227 suicide notifications had a response from the inspectorate, and 278 notifications had no follow-up. The selection of notifications was conducted in this manner to permit comparison of cases with and without a response and to determine whether inspectors responded more frequently to certain patient or treatment characteristics. A pen-and-paper instrument was used to gather data on relevant characteristics, including patients' demographic characteristics and the responses of the inspectorate.

Responses to suicide notifications by inspectors were examined both quantitatively and qualitatively. The nature of the response was classified into three categories: a request for additional information, remarks or suggestions for improvement, and further contact with the mental health service or other involved services.

All responses were also subjected to a detailed qualitative analysis, facilitated by ATLAS.ti software. An open coding scheme was derived from the questions and remarks of the inspectors, and every response was assigned a preliminary code independently by the first two authors. The codes were further refined, and a clear definition was generated for each until a comprehensive coding scheme was created that accurately reflected the responses. By use of this coding scheme, each response was reviewed independently by the second author, and inconsistencies in coding were discussed until agreement was reached.

The responses of the inspectorate to suicide notifications were then compared with the American Psychiatric Association's (APA's)

Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors (

6 ) to establish whether the responses were in accord with the guideline. The guidelines note that the most important aspects are frequent suicide risk assessments on the basis of protective and risk factors, treatment planning to reduce suicide risk, continuity of care, and a restrained use of no-suicide contracts.

The relationship between characteristics of the suicide notifications and the likelihood of a response by the inspectorate was examined by cross-classifying whether or not the inspectorate responded on the basis of patient and treatment variables (age, gender, diagnosis, suicide method, inpatient versus outpatient status, discharge from inpatient care, duration of treatment, warning signals of suicide, discussion of suicidality with the therapist, and lessons learned as a result of the suicide). Chi square tests were computed on that distribution, and the significance threshold was set at .01 to compensate for the possibility of finding significance by chance when conducting such a large number of comparisons.

To determine whether the management of suicide notifications by the inspectorate had changed between 1996 and 2006, responses from recent years (2002–2006) were compared with those from an earlier period (1996–2001) by using chi square tests.

Results

Patient characteristics

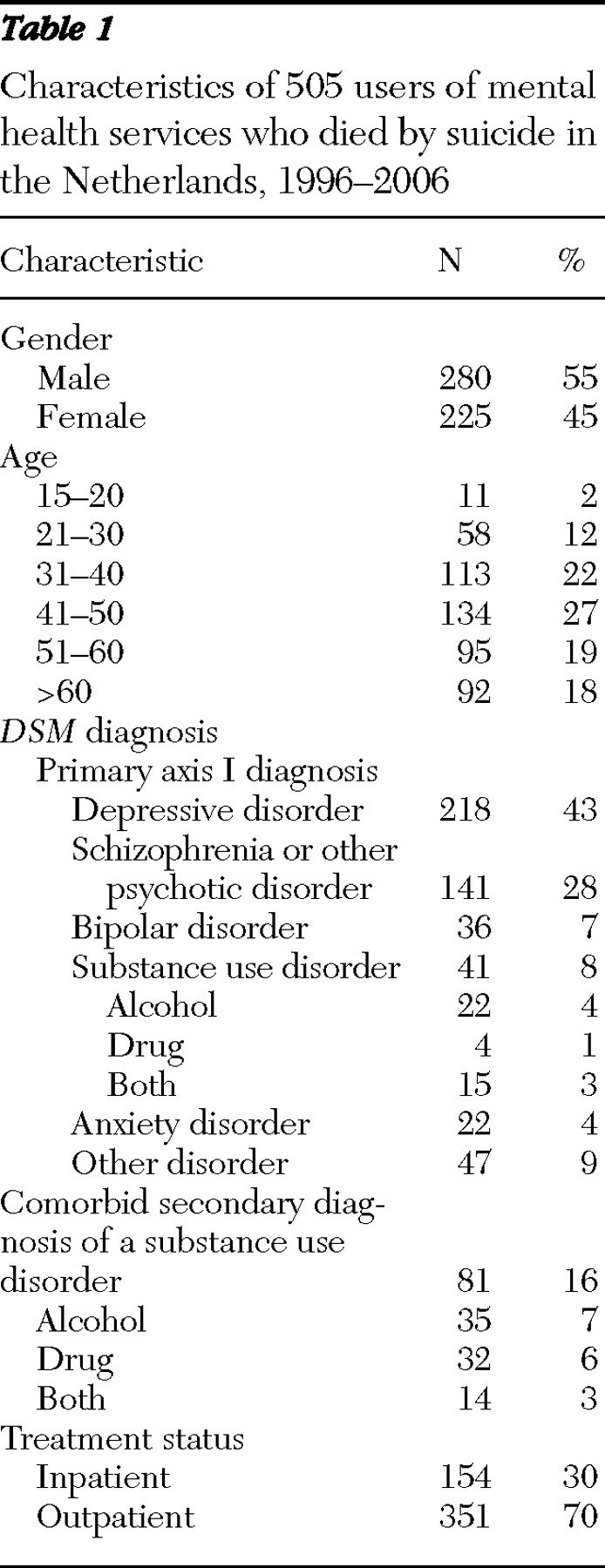

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are summarized in

Table 1 . A typical patient was a middle-aged male in outpatient treatment who had a diagnosis of depression.

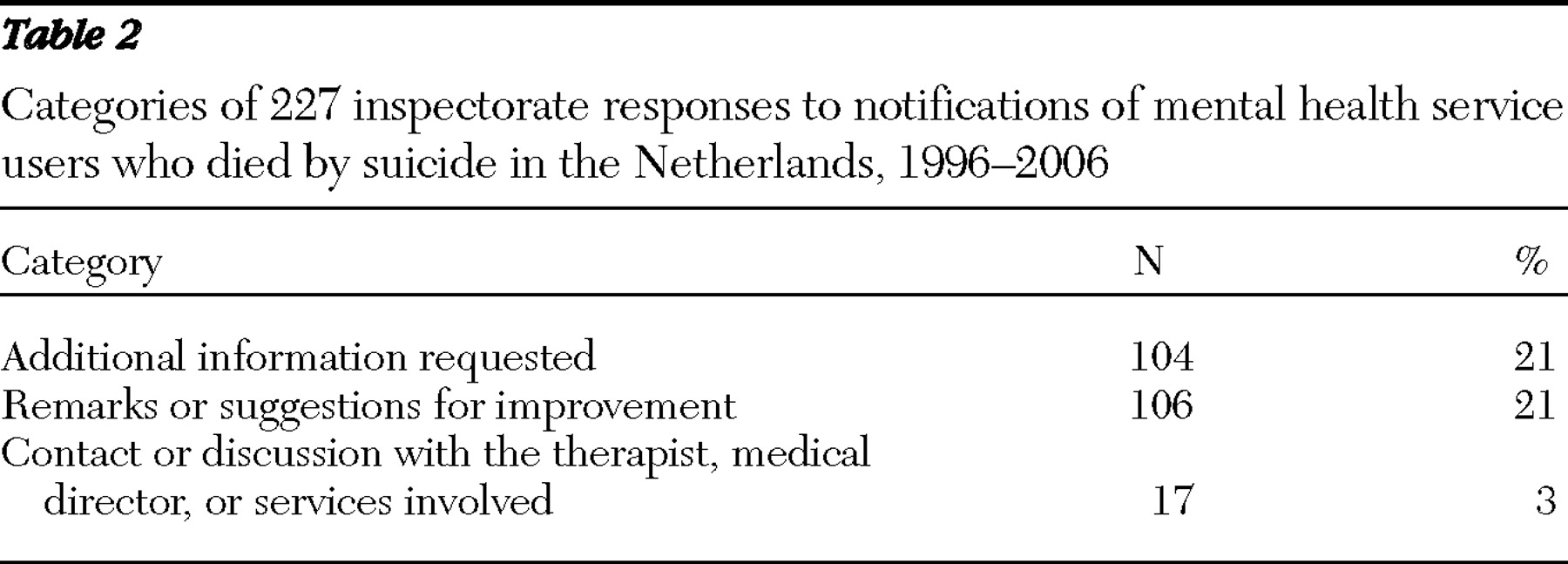

The number of responses to suicide notifications in each of the three categories is shown in

Table 2 . Inspectorate responses for 227 of the 505 suicide notifications were examined. The inspectorate responded to 75 of the 205 notifications (37%) in 2006.

Qualitative analysis of responses

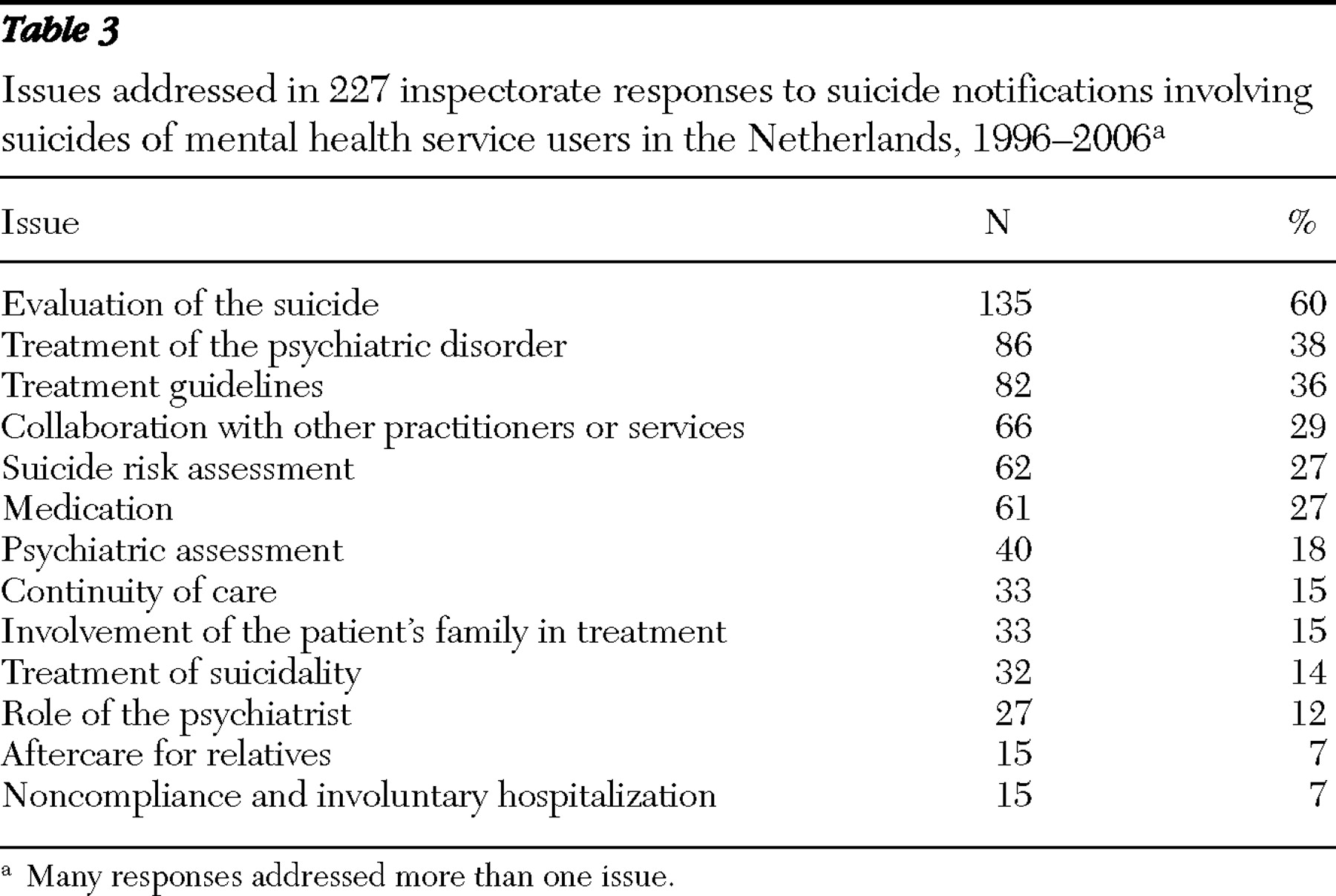

The inspectorate's responses to the suicide notifications were classified into 13 broad categories (

Table 3 ). The greatest number of questions or remarks concerned evaluation of the care provided to the patient. The most common question in this respect was, "Has the suicide been evaluated and what were the results of the evaluation?" Other frequently asked questions involved whether the patient received adequate treatment for his or her psychiatric disorder. Questions also addressed the nature, purpose, and progress of the treatment and the clinician's decisions about appropriate treatment settings.

The importance of adherence to treatment guidelines was stressed by the inspectorate in 36% of the responses. In the Netherlands there are national guidelines for the treatment of various psychiatric disorders but not for suicidality. The responses often contained questions about whether the clinician adhered to the treatment guidelines for the psychiatric disorder in question. Another question addressed whether guidelines for the treatment of suicidal patients were in place at the agency, and if so, whether the clinician adhered to them. In the case of responses to notifications of suicides by inpatients, questions were asked about policies on safety, patient privileges, and monitoring.

In 29% of the responses the questions or remarks addressed collaboration with other practitioners or services, and in 15% continuity of care was a focus. These questions and remarks were made most frequently in responses that involved suicide among patients who had been recently discharged from inpatient care or who had changed treatment setting. The responses addressed transfer of information and consultation between therapists or services involved in the patient's care and the frequency of aftercare appointments.

Suicide risk assessments were addressed in 27% of the 227 responses. Most common were questions about whether and how risk assessment took place and whether suicidality was discussed periodically with the patient. Specific remarks addressed the importance of telling the patient about an elevated suicide risk in the first weeks of using antidepressant medication, taking the expression of suicidal ideation or behavior seriously, and communicating about suicide risk with other therapists involved in the patient's care.

Questions about medication (included in 27% of responses) and about psychiatric assessment (18%) were usually straightforward: what medication was prescribed, or what was the DSM psychiatric diagnosis? Other questions involved the assessment of the primary psychiatric disorder and any comorbid disorders, the accuracy of diagnoses, and the appropriateness of the medication.

In 14% of the responses the questions and remarks specifically referred to management of the patient's suicidal impulses. Generally, this involved a question about whether and how the therapist had managed this risk.

Fifteen percent of responses included questions or remarks about the involvement of the patient's family, and 7% addressed aftercare for the bereaved relatives. The inspectorate stressed that mental health services must involve the patient's family in the assessment and treatment of suicidal patients and must offer aftercare to the bereaved family after a suicide.

The significance of the role of the psychiatrist was emphasized in 12% of the notifications. In some cases the patient had not been seen by a psychiatrist. The inspectorate took the position that a psychiatrist must exercise responsibility and see patients personally, especially in assessment of psychiatric disorders and suicide risk and prescription of psychotropic drugs.

Seven percent of responses concerned the patient's treatment noncompliance and issues regarding involuntary hospitalization. In these cases, the patient usually refused mental health care or regularly missed appointments, to which the therapist did not take an active approach. The inspectorate recommended in these cases that noncompliant patients must be approached more actively by mental health services. Other responses included a question about whether involuntarily hospitalizing the patient was considered and whether it would have been better to have done so.

Critical remarks and suggestions for improvement

The inspectors made critical remarks in 106 notifications. They addressed the lack of guidelines for suicide prevention, the lack of sufficient continuity of care and collaboration between therapists involved, insufficient involvement of a psychiatrist in suicide risk assessment and prescription of medication, inadequate assessment of suicide risk, inadequate psychiatric treatment and inaccurate psychiatric diagnosis, and insufficient attention to communication and signals from relatives of the patient.

Characteristics associated with inspectorate responses

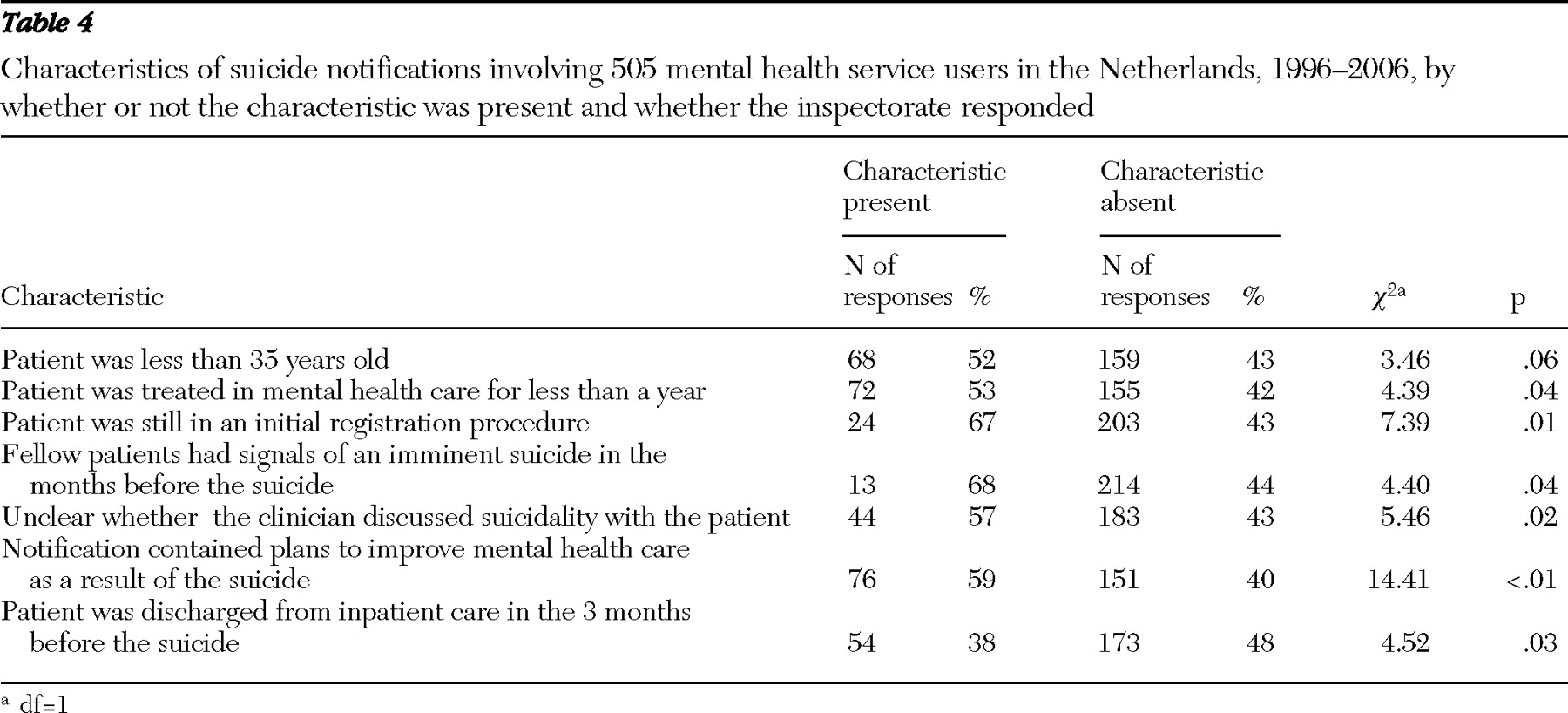

Characteristics of the suicide notifications to which inspectors responded more or less frequently are summarized in

Table 4 .

Changes in responses 1996–2006

In the 2002–2006 period inspectors were significantly more likely to emphasize the importance of suicide risk assessment than in the 1996–2001 period (37% and 19%; χ 2 =6.4, df=1, p= .01). In addition, the content of responses about risk assessment appears to have changed. In earlier years questions were simpler and mainly addressed whether risk was assessed. In the later period questions were more elaborate and more often required a detailed assessment on the basis of risk factors for suicide.

For all other variables (listed in

Table 3 ) no differences were found.

Correlation between responses and APA guidelines

In general, the inspectorate's 1996–2006 responses were in line with APA guidelines. Important aspects of the responses were adequate psychiatric treatment, cooperation with other therapists involved in the patient's care, continuity of care, and provision of aftercare for the bereaved family. In addition, responses about suicide risk assessment corresponded increasingly with the guidelines in the most recent years examined.

However, use of no-suicide contracts was addressed only once in all 227 of the inspectorate's responses to suicide notifications, although 23% of the notifications indicated that a no-suicide agreement was arranged with the patient, including patients who had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, highly impulsive patients, and those with serious addiction.

Suicide notifications without follow-up

The 278 suicide notifications without follow-up by the inspectorate were studied qualitatively to gain more insight into possible reasons for a lack of follow-up and to determine whether there were, despite the lack of follow-up, indications of structural problems in the mental health care provided. From the perspective of the APA guidelines, several possible signs of shortcomings in the mental health care provided were observed and are discussed below.

Incomplete or inadequate risk assessment. In 59 notifications without follow-up (21%), therapists underestimated the risk of suicide despite the presence of several risk factors. Previous suicide attempts were labeled as "merely a cry for help" in nine notifications, and thus the suicide risk was estimated to be low. In addition, in nine cases mental health care workers were unaware of the suicidal history of the patient or knew nothing about suicidal intent expressed by the patient to family members or fellow patients by the patient.

Another problem in the area of poor risk assessment was that attentiveness to suicide risk had waned, especially for patients who had a history of severe suicidality but who did not report current suicidal ideation (N=15) and for patients who were chronically suicidal (N=15).

Insufficient continuity and intensity of care. Continuity of care was not always adequate. In 11 notifications without follow-up, the patient committed suicide while on a waiting list for treatment or while involved in a registration procedure that lasted several months, despite the patient's severe psychiatric symptoms or crisis. In 14 cases that were not followed up by the inspectorate, follow-up appointments after discharge from inpatient care took weeks or months (range of three weeks to three months). In 17 other cases the emergency service did not assess suicide risk in time or did not make an appointment with the patient within a few days of referral or of the patient's initial contact with services, and the patient committed suicide before being seen.

Unwarranted trust in no-suicide contracts. In 28 notifications without follow-up, a no-suicide contract was arranged with a patient and the therapists involved considered the suicide risk to be reduced. In seven cases the patient's willingness to enter a contract was sufficient to result in transfer to an open ward. Moreover, in five cases arrangement of a no-suicide contract seemed to be the only safety measure taken; other measures, such as more intensive care or a safety plan, were not carried out.

Inadequate decisions about hospitalization. In 14 cases without follow-up, patients in crisis weren't hospitalized because hospitalization was thought to be risk enhancing, presumably because these patients had a personality disorder. In addition, seven patients committed suicide while on a waiting list for inpatient admission.

Inadequate communication. Inadequate communication between mental health care workers, especially about suicidality, may have led to insufficient transfer of information and suicide risk management in 19 notifications for which no follow-up was received.

Insufficient monitoring of severely depressed or psychotic patients. For six notifications that involved suicide of a hospitalized patient and for which no follow-up was received, the patient was able to run away from a closed ward on repeated occasions.

Inadequate communication with the patient's family. In 16 cases without follow-up, the patient's relatives were either unable to discuss their concerns about the suicidality of their relative with the therapists or they were not involved in treatment despite the patient's severe suicidality.

Discussion

This study was undertaken as a first step in a research program to evaluate the suicide notification procedure administered by the Health Care Inspectorate in the Netherlands. The results show that in 2006 approximately 37% of all mental health workers who reported a suicide received further questions or remarks from the inspectorate. Inspectors' responses were mostly focused on the thorough evaluation of circumstances and care surrounding the suicide. Another main point of interest to the inspectorate was the treatment of psychiatric disorders in accordance with treatment guidelines. Compared with responses to suicide notifications between 1996 and 2001, recent responses have more often stressed the importance of conducting suicide risk assessment, which is in line with APA guidelines.

Certain aspects of the notifications led to more or less frequent responses. Inspectors' responses depended on the treatment status of the patient who died by suicide and tended to depend on the patient's age and time in treatment. The proportion of responses was larger for patients who were young or at the beginning of treatment, and it was smaller for patients who were recently discharged from inpatient care. These findings suggest that the inspectorate focuses especially on patient groups and time periods for which suicide prevention efforts are considered most effective. Apparently inspectors believed that there were few opportunities for prevention among elderly persons, those with chronic illnesses, and those in the postdischarge period, although patients in the postdischarge period are widely recognized to be at high risk of suicide (

7 ). There may be opportunities for the inspectorate to emphasize more effective suicide prevention in the postdischarge period.

Inspectors tended to pay special attention to suicides in which fellow patients had noticed signals of an imminent suicide in the months before and when it was unclear whether the clinician had discussed suicidality with the patient or whether the patient had been treated as suicidal. These aspects were apparently regarded as important considerations for suicide prevention. Moreover, these findings may demonstrate the gradually growing awareness in the field and within the inspectorate that suicidal impulses need specific attention in addition to the usual treatment for psychiatric disorders. The inspectorate could further promote such awareness, as recommended in the APA guidelines.

A notable result is that only one of the inspectorate's 227 responses addressed use of no-suicide contracts, although such contracts were used in about one in five of the cases reviewed by the inspectorate. Contracts were made with patients who had addictive or psychotic disorders or who were highly impulsive, which is discouraged by APA guidelines for the treatment of suicidal patients (

6 ).

The inspectorate was more likely to respond to a suicide notification when mental health institutions attached plans for improvement to the notification. In its responses the inspectorate both supported the intended improvements and acknowledged the flaws in the mental health care delivery that the institutions themselves admitted. However, in some cases the inspectorate did not respond, although the notification contained indications of possible flaws in care delivery. This finding seems to indicate that the inspectorate neglected to address some shortcomings. Moreover, inspectors did not respond in the same manner to all notifications involving the same themes, which suggests a somewhat arbitrary element.

In general, mental health care providers are concerned about possible disciplinary measures by the inspectorate; however, the findings of this study show that in cases of suicide notifications, such measures seldom follow. In none of the inspectorate's 227 responses to suicide notifications were disciplinary measures taken, and only a small percentage (3%) of suicide notifications led to an extensive inquiry into the case.

Some limitations should be noted. The results of this study depend on the quality and comprehensiveness of suicide notifications. Additional research is in progress to evaluate these aspects of the notifications. The results of the qualitative analyses are based on the authors' interpretations of whether treatment was consistent with APA guidelines (

6 ) and therefore are not conclusive. In addition, a relatively large number of tests were conducted, and it is possible that some associations were found by chance. Replication is needed to confirm the factors that determine whether the inspectorate responds to a notification.

The notification procedure is meant to provide supervision of the quality of health care service delivery and to improve care for suicidal patients in the future. As such the inspectorate's procedure can be a powerful tool in promoting suicide prevention. Further research is in progress to examine the influence of the suicide notification procedure on the quality of care in mental health services and to examine how mental health services view the notification procedure.

Conclusions

The results show that supervision in mental health care can be optimized in accordance with guidelines for the treatment of suicidal patients. The inspectorate might enhance its review procedure by more consistent supervision, continuing emphasis on systematic suicide risk assessment, more emphasis on the specific treatment of suicidal impulses, more attention to the treatment of older patients who are chronically suicidal and to patients newly discharged from inpatient care, and more focus on a restrained use of no-suicide contracts.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by the Health Care Inspectorate in the Netherlands.

The authors report no competing interests.