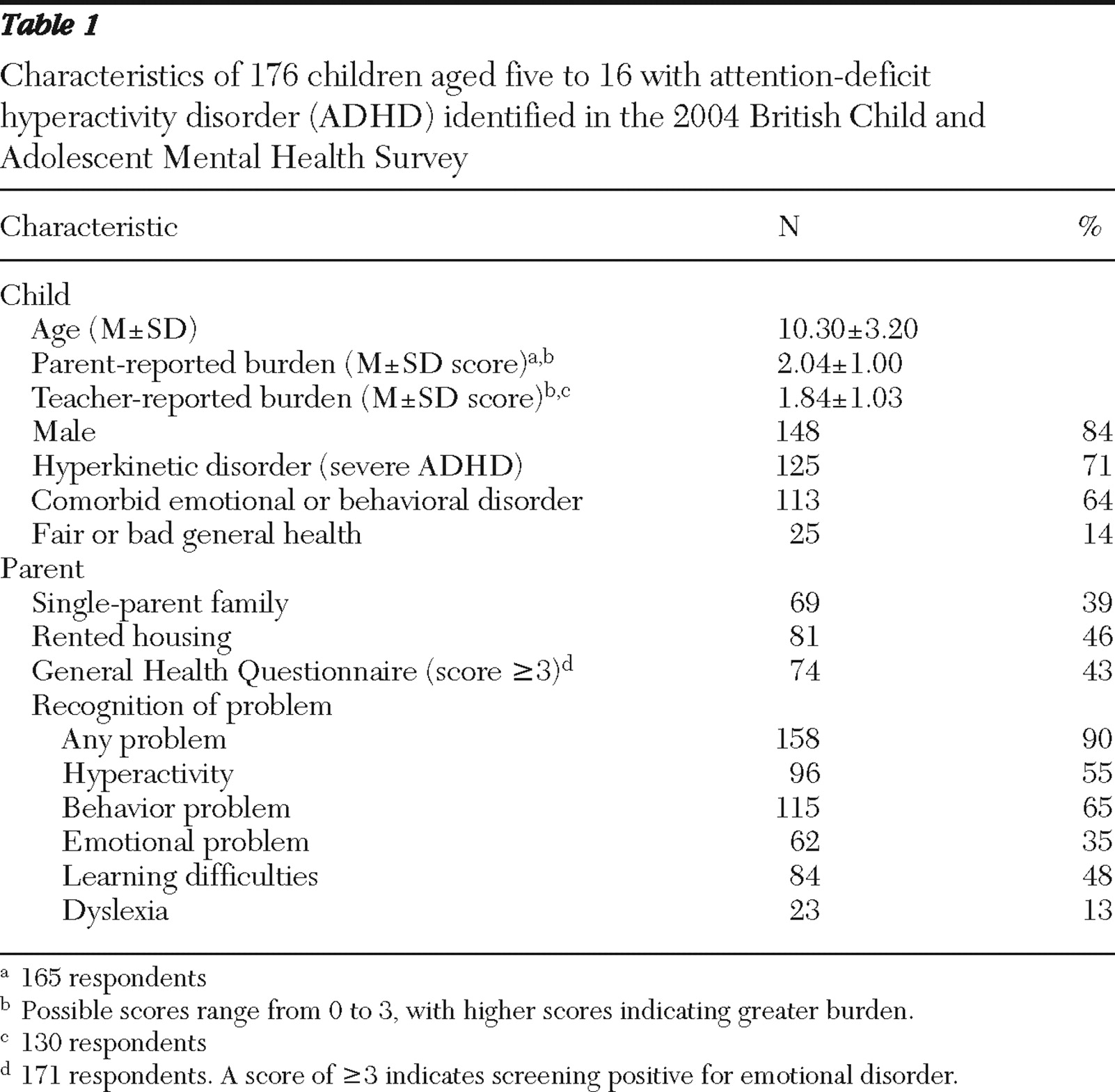

Sample

The 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey. Data from the 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey (B-CAMHS) were used. It had a nationally representative sample of 7,977 children aged five to 16 who were identified through child benefit records (76% response rate). The sampling methodology was similar to that used in the 1999 survey, and details of recruitment and representativeness have been reported elsewhere (

9,

10,

11 ). Diagnostic information in both surveys was based on the reliable and well-validated Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) package that included a teacher questionnaire and a structured interview with the parent and child (if age 11 or older) that was administered by trained lay interviewers, who also recorded verbatim accounts of reported problems (

10,

12 ). Participants provided written informed consent. Most families (94%) gave permission to contact teachers, and teachers provided information for 83% of children.

To emulate the clinical diagnostic process as closely as possible, experienced clinicians reviewed all the available information and assigned diagnoses of ADHD using

DSM-IV criteria (

13 ) and hyperkinetic disorder using

ICD-10 criteria (

14 ). When relevant, they also took medication information into account to ensure that children receiving treatment for ADHD were given a research diagnosis of ADHD if appropriate. For this study, we focused on the 176 children who met criteria for ADHD (weighted prevalence rate of 2.2%). In keeping with British clinical guidelines (

15 ), we did not exclude children who also met criteria for an autistic spectrum disorder (N=18). Ethical approval for the clinical rating and secondary analysis of these data was obtained from local and multicenter research ethics committees.

The 1999 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey. This different sample of children aged five to 15 with ADHD (N=238) was identified by using a methodology similar to that used for the 2004 survey, which has been described elsewhere (

1 ). To ensure equivalent samples in comparative analyses across the two periods, we also included children who met criteria for both ADHD and an autistic spectrum disorder (N=6).

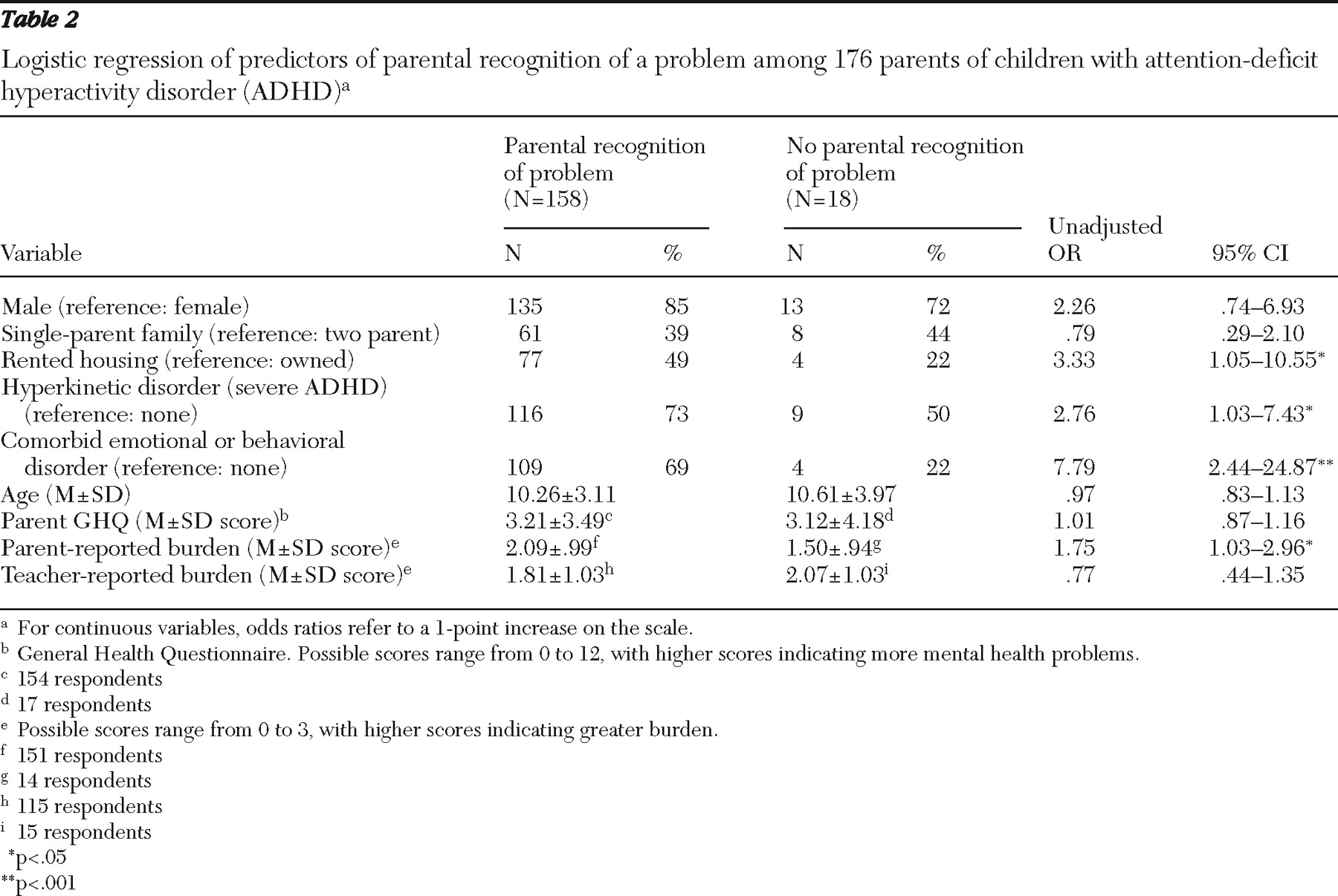

Measures

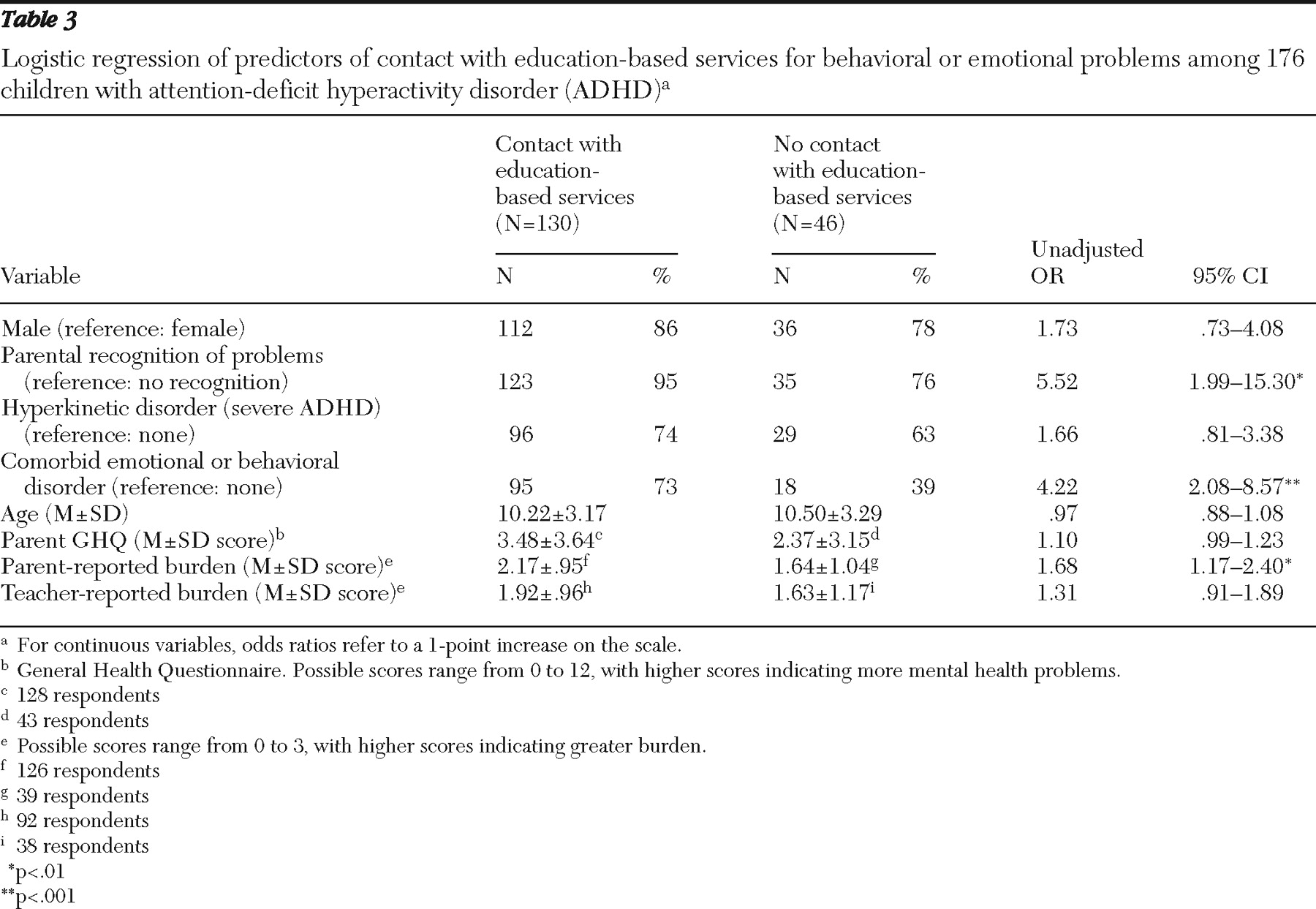

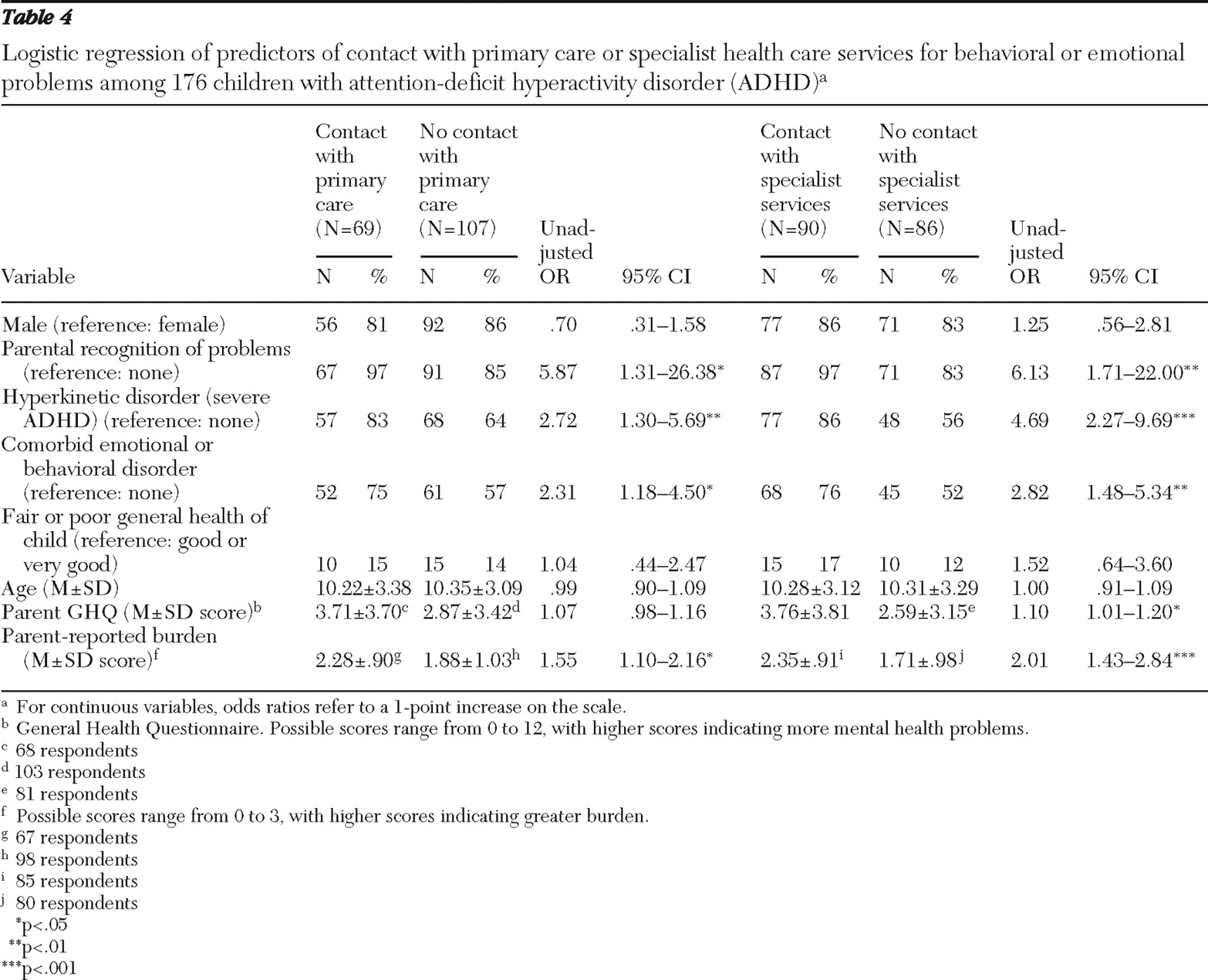

Outcome measures. We report three main outcomes. First, before the DAWBA interview was carried out, we assessed parental recognition of problems. Parents were asked whether they thought that their child had any of the following current problems: hyperactivity, behavioral problems, emotional problems, learning difficulties, and dyslexia. Second, parents were asked whether they or their child had been in contact over the past year with professionals (such as teachers, professionals in specialist education services, primary health care providers, specialist health care providers, social workers, or others) about concerns relating to emotions, behavior, or concentration. Parents could indicate all applicable services.

We focused on contact with education-based professionals (teachers, educational psychologists, and school counselors), primary health care providers (general practitioners and nurses), and specialist health care providers (in pediatric services or child or adult mental health services). Clinical practice guidelines recommend that only specialist health care services should carry out diagnostic assessments and initiate medication for ADHD (

5,

15 ). In the 1999 survey, service use information reflected lifetime contact with services. Third, information about medication use was elicited by showing parents a list of commonly used psychoactive drugs with both nonproprietary and brand names.

Predictor measures. Sociodemographic measures included child gender, child age, living in a single-parent family, and house ownership. Parents rated their child's general health on a 5-point scale: very good, good, fair, bad, or very bad. This item, which was developed for these surveys, was dichotomized for analyses as good and very good versus fair, bad, and very bad health. Parental recognition of problems (as defined above) was examined as a predictor of service use. The General Health Questionnaire, a well-validated 12-item self-report questionnaire with established psychometric properties, was used to measure parental mental health (

16 ). Each item is scored 0 or 1, and the B-CAMHS used a cutoff score of ≥3 as an indicator of screening positive for emotional disorder. This cutoff has high sensitivity and specificity for common psychological disorders.

Clinical measures were taken from the DAWBA. Severe ADHD was indicated if the child met criteria for hyperkinetic disorder; clinical guidelines in Britain have conceptualized hyperkinetic disorder as "severe ADHD" (

15 ). Compared with children with ADHD, children who also meet criteria for hyperkinetic disorder have more severe symptoms and impairment in academic and cognitive functioning and have a greater response to medication treatment (

17 ). Comorbidity reflected the presence of a comorbid anxiety, depressive, or oppositional-conduct disorder (

14 ). To assess parent and teacher ratings of hyperactivity-related burden, informants were asked whether the difficulties placed a burden on them or the family or class (if relevant) on a 4-item scale: not at all, only a little, quite a lot, and a great deal. This measure of burden is specific to hyperactivity-related symptoms. The wording is the same as the burden item in the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (

18 ). The rating correlates well (r=.74) with the Child and Adolescent Impact Assessment, which is a standardized interview rating of the impact of the difficulties on the caregiver (

18,

19 ).

Analyses

For the 2004 ADHD sample, we carried out three main sets of comparisons: between parents who did and did not recognize a problem, between children who had used particular types of services and those who had not, and between children who did and did not receive medication. Previous analyses of data from these surveys have shown that weights are not necessary to investigate risk (

9 ). Therefore, we used unweighted data, which reflect the sample of 176 children with ADHD.

The number and choice of predictor measures for specific outcomes reflected the sample size for each comparison and findings reported in the literature (

1,

8,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27 ). For the outcome of parental recognition of problems, on the basis of the literature (

1,

20,

22,

24,

25,

26 ), we examined the predictive roles of gender and age of the child, severity of the disorder, comorbidity, parental mental health, marital and housing status (as markers of socioeconomic status), and adult-reported burden. For the service use and medication outcomes, on the basis of the literature (

1,

8,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27 ), we examined the predictive roles of severity of ADHD, comorbidity, parental mental health, parental recognition of problems, and adult-reported burden. The main differences in the choice of predictor measures for service use reflected the possible roles of teacher-reported burden for contact with education and the child's general health for contact with health services.

We initially examined the univariable relationships between predictor and outcomes measures using logistic regression analyses to provide odds ratio (OR) estimates. Predictors with an association (p<.05) were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model to provide adjusted ORs.

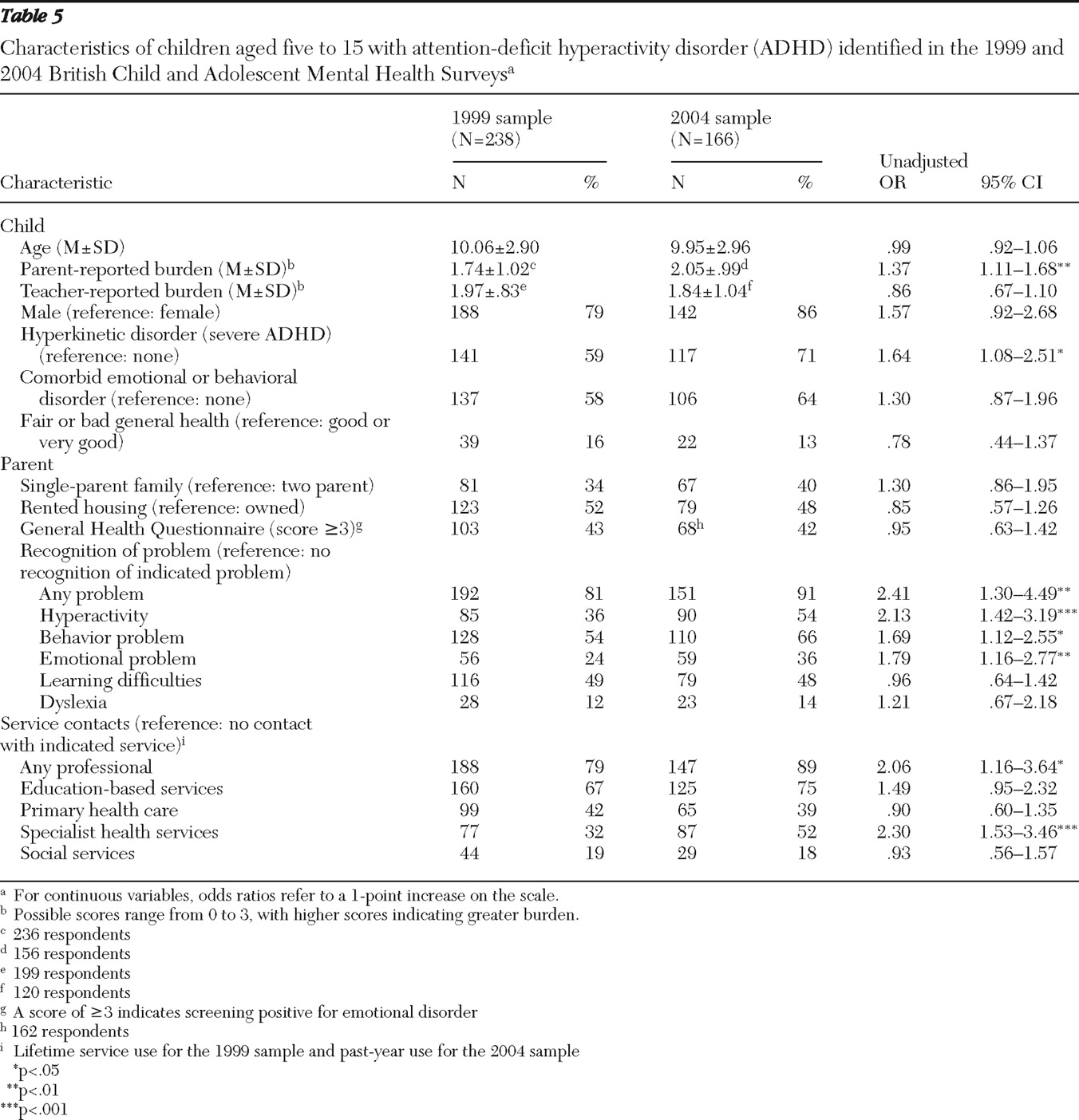

To compare the ADHD samples from 1999 and 2004, before we combined the two data sets, ten 16-year-olds were excluded from the 2004 sample to ensure equivalent samples (five- to 15-year-olds) in comparative analyses. First, to investigate statistical changes in correlates of service use over time, we assessed for interactions between the sample (1999 or 2004) and individual predictors, and we report any associations (p<.05). The samples from 1999 and 2004 were then compared by using logistic regression analyses to provide OR estimates. Finally, multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the roles of year, severity of ADHD, parental recognition that the child has hyperactivity, and parental burden as predictors of specialist service use.