Participant description

Participants were the biological mother (N=36, 75%), biological aunt or grandmother (N=5, 10%), biological father (N=4, 8%), or stepparent (N=3, 6%) of the child. Most were single parents (N=37, 77%) and living in an urban community (N=42, 88%).

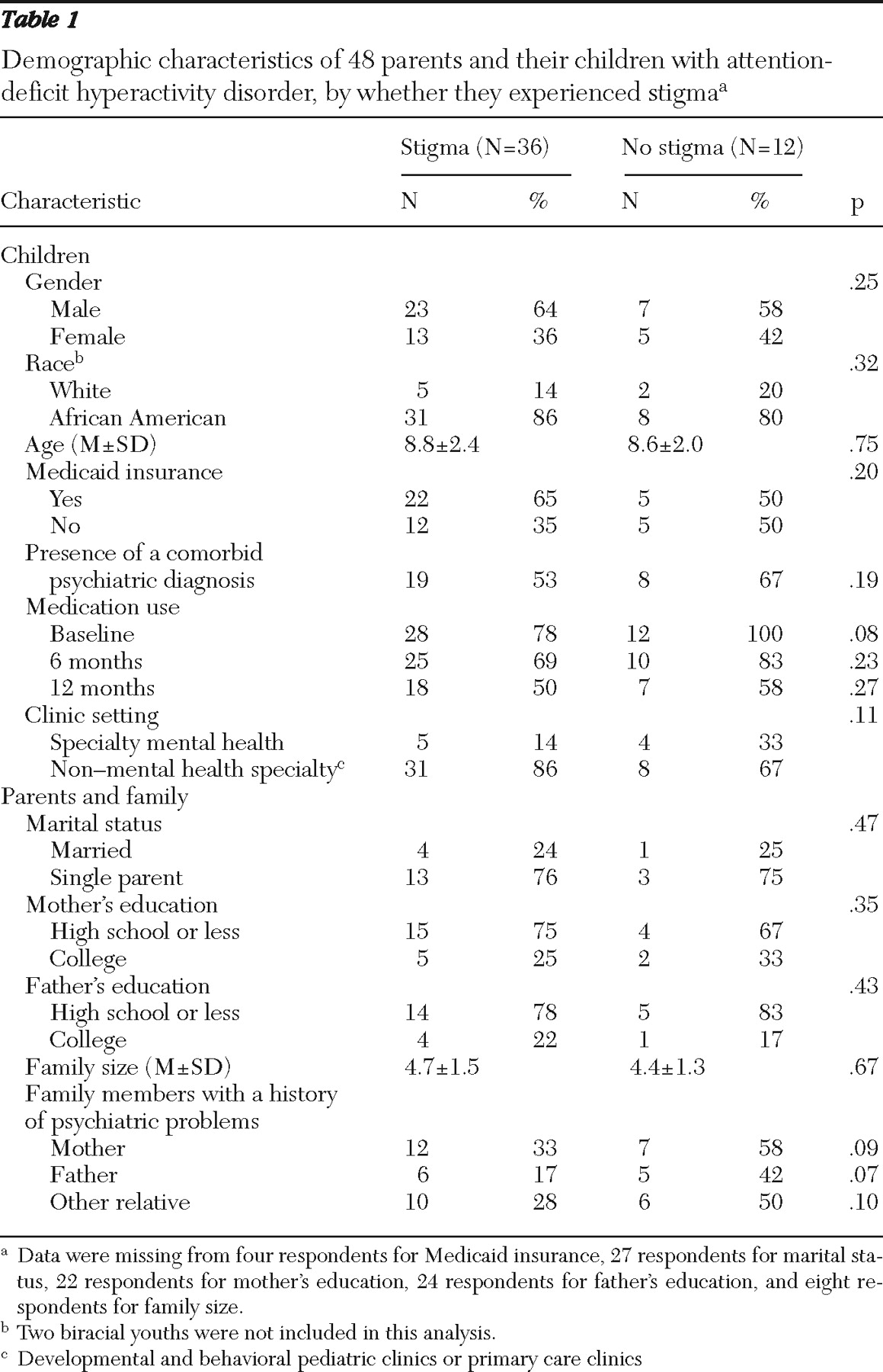

Children were mostly African American and male; they had a mean±SD age of 8.8±2.3 years. Twenty-seven (56%) had comorbid diagnoses, which included adjustment disorder (N=11, 23%), learning disorder (N=8, 17%), depression or anxiety disorder (N=7, 15%), and disruptive disorder (N=5, 10%). Nearly half (N=23, 48%) had a family psychiatric history (14 children, or 29%, with a family history of substance abuse; 11 children, or 23%, with a family history of depression). Stimulant use was noted within one month after receipt of the diagnosis for 40 children (83%).

Thematic constructs of stigma

Parents reported their perceptions of the stigmatizing experiences and beliefs in regard to their child's ADHD diagnosis and medication. Six thematic constructs emerged: concerns with labeling, feelings of social isolation and rejection, perceptions of a dismissive society, influence of negative public views, exposure to negative media, and mistrust of medical assessments. Eleven parents (23%) did not endorse any of the six thematic constructs of stigma.

Concerns with labeling. Many (N=21, 44%) did not want society to label their child as a "bad kid," a "problem child," or a "troublemaker." Some parents were concerned that, as a result of their child's misbehavior, they would be perceived as "bad parents," as not disciplining their child, or as using the behavior to get special privileges. Some parents themselves labeled their child as not a "regular kid" or "normal" like comparable age peers. Another concern was that as a consequence of being labeled, their child would be treated differently or not given the same opportunities as their peers.

Feelings of social isolation and rejection. Also common (N=19, 40%) were parents' and their child's social isolation and rejection from peers, family, and the community. All accounts of isolation and rejection were related to concerns that their child would have low self-esteem and be lonely and sad. Specific accounts were that society does not want to deal with a "child that doesn't follow directions." Parents disliked school policies that isolated their child from their peers, such as pulling children out of the classroom to get their midday dose of medication or placing the child's desk away from other children in the classroom. Parents were especially bothered by other children who were "mean" and constantly "picking" on their child. Parents also felt isolated because they were not able to talk about their child's achievements like other parents. Rather, they felt like they were the "one who has the child that has problems."

Perceptions of a dismissive society. Just over one-fifth (N=10, 21%) of parents felt that their concerns were being dismissed by primary medical professionals and school personnel. Parents asserted that living with and raising a child with ADHD provided them with some knowledge of what was best for their child. One parent noted, "I felt being a parent, you know, they're not listening to me." The perceptions of being dismissed by these individuals led parents to seek supportive services from behavioral specialists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social service agencies.

Influence of negative public views. Three parents (6%) had a close relative with strong negative opinions of medication, and thus parents were influenced by these views. For example, parents noted how these individuals would openly express their negative opinions by saying, "doctors always say something is wrong with a child and [want to] put them on medicine." This became embedded in parents' view of medication and their willingness to use it or even consider using it for their child.

Exposure to negative media. Ten parents (21%) held their own stigmatizing beliefs of the "bad things" or "horror stories" they had witnessed with stimulant treatment of children of relatives or friends or that they had seen in the media. They spoke specifically about "zombielike" effects and children looking like they were "drugged." Others associated medication treatment with substance abuse and the potential for addiction because of the medication's controlled substance designation by the Food and Drug Administration. Consequently, parents were concerned about subsequent failure in life if their child was unable to learn the material being taught in school because the child was "drugged."

Mistrust of medical assessments. Additionally, eight (17%) expressed mistrust of medical assessments. They believed the checklist items could be answered to "guarantee" their child would be placed on medication. They perceived that clinicians had no interest in trying to "work it out" before using medication. Several parents suggested that clinicians were too quick to medicate a child with ADHD; one parent said, "as soon as I took him [to the clinic] that would be the first thing they would say."