Case management services

A total of 203 subjects (78 percent) received some case management services in jail. The median total amount of services they received was 40 minutes, with two-thirds receiving less than an hour and 15 percent receiving more than two hours.

Case management fell off dramatically after subjects left jail. As

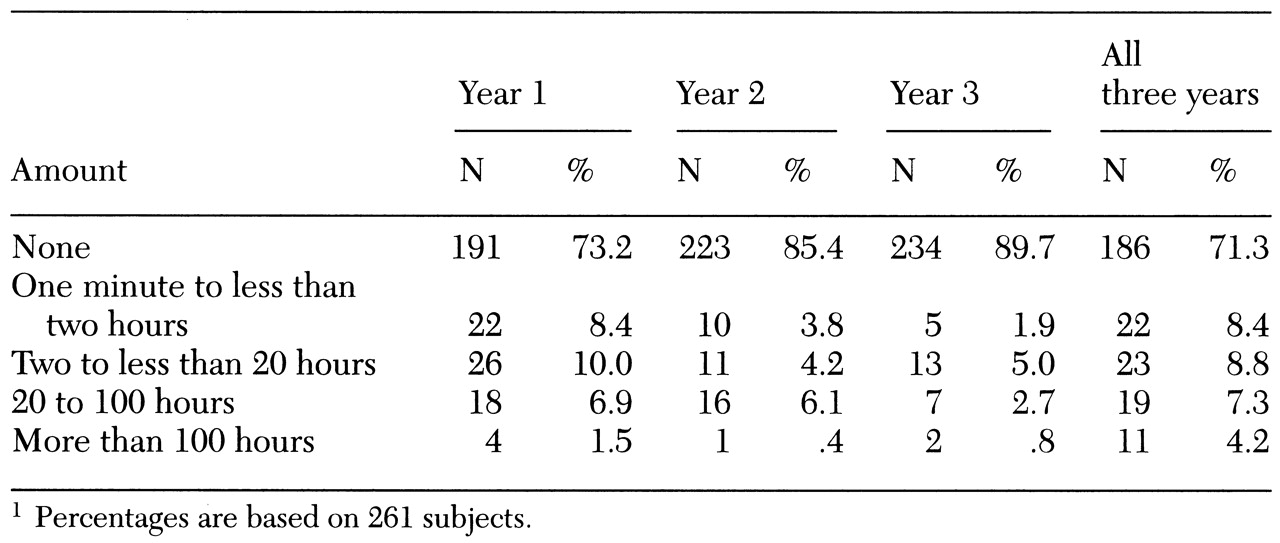

Table 1 shows, only 75 subjects (29 percent) received any community case management in the three years after release. Whether a subject received community case management was determined by both the subject's receptiveness and the program offerings of the community mental health center serving the subject's area of residence. Receipt of case management after release from jail was voluntary. Furthermore, the percentage of subjects receiving community case management declined over time, from 27 percent the first year to 15 percent the second year and 10 percent the third year.

The amount of case management services subjects received was recorded until their first arrest after release. Each month a subject was in the community (before the first arrest) constituted one person-month at risk of arrest. Hypothetically, therefore, if all 261 subjects avoided arrest over the entire three-year study period, they would have accumulated a total of 9,396 person-months at risk (261 subjects × 36 months). Because some of the subjects were arrested, however, the number of person-months at risk was 4,454.

Recipients of community case management

Compared with subjects who did not receive community case management, recipients of community case management were significantly younger (29 versus 32 years; F=8.814, df=260, p<.01) and more likely to be legally classified as severely mentally disabled (34 percent versus 15 percent; χ2 =8.395, df=1, p<.01). Recipients were also more likely to have psychotic symptoms on admission to jail (62 percent versus 18 percent; χ2 =44.616, df=1, p<.001), to be diagnosed as having schizophrenia (66 percent versus 19 percent; χ2 = 45.880, df=1, p<.001), to have previous psychiatric hospitalizations (44 percent versus 15 percent; χ2 =25.612, df=1, p<.001), and to have been found not competent to stand trial (60 percent versus 28 percent; χ2 =4.963, df=1, p<.05). (It should be noted that in the jurisdiction where the study was conducted, defendants who are found incompetent to stand trial typically are transferred briefly to a local state psychiatric hospital and then back to jail.)

In addition, subjects who had more severe disorders, as measured by each of the indicators listed above, received far more community case management services, on average, than did subjects whose disorders were less severe.

Typically, the most recent arrest of subjects who received community case management was for a violent misdemeanor (34 subjects, or 45 percent). They had fewer previous felony arrests than those who did not receive community case management (2.5 versus 3.7 arrests; F=4.384, df=260, p<.05) but longer pretrial jail stays (means=47 and 33 days; F=5.399, df=260, p<.05).

Subjects released from jail on probation (to community supervision immediately after conviction) or parole (to community supervision after serving a term in jail after conviction) were equally likely to receive community case management as subjects released directly to the community.

Recidivism

During the follow-up period, 188 of the 261 subjects (72 percent) were rearrested. Among those with the most serious charges, 60 (23 percent) were arrested for violent misdemeanors, 50 (19 percent) for nonviolent felonies, 36 (14 percent) for nonviolent misdemeanors, 29 (11 percent) for violent felonies, and 13 (5 percent) for parole or probation violations. Rearrest typically occurred quickly; 107 subjects (41 percent) were rearrested within six months, and 138 (53 percent) were arrested within one year.

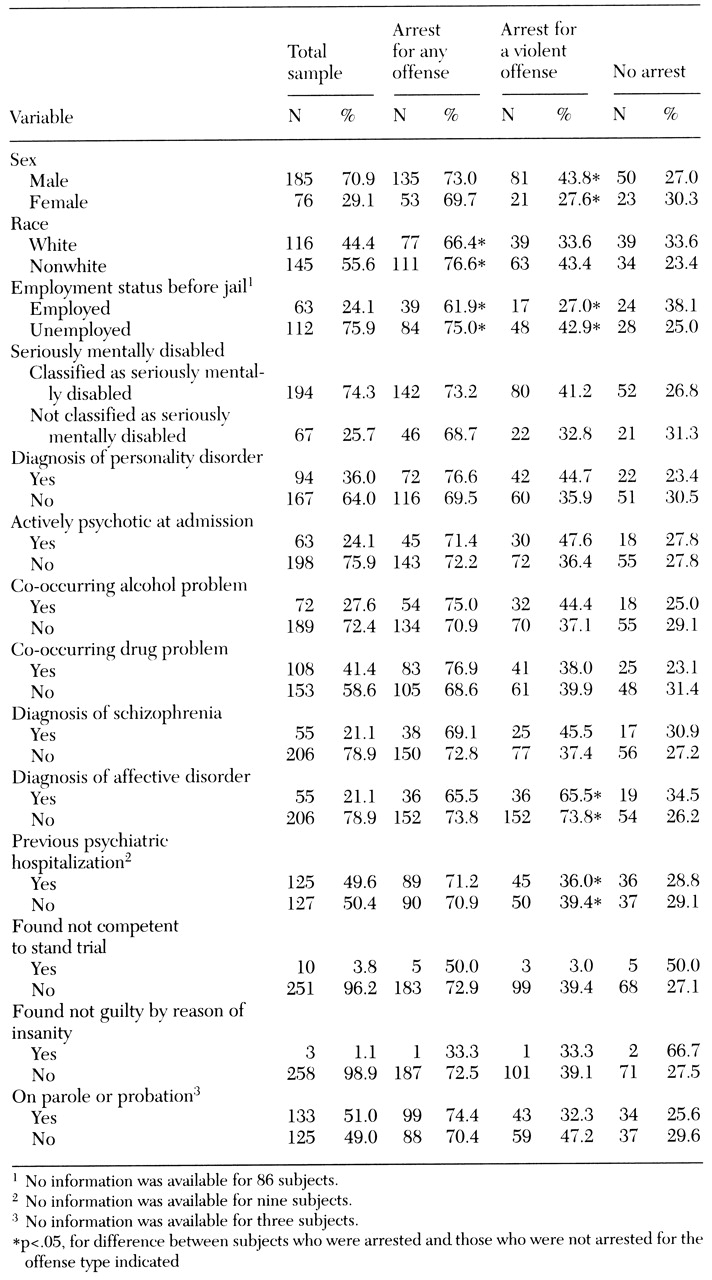

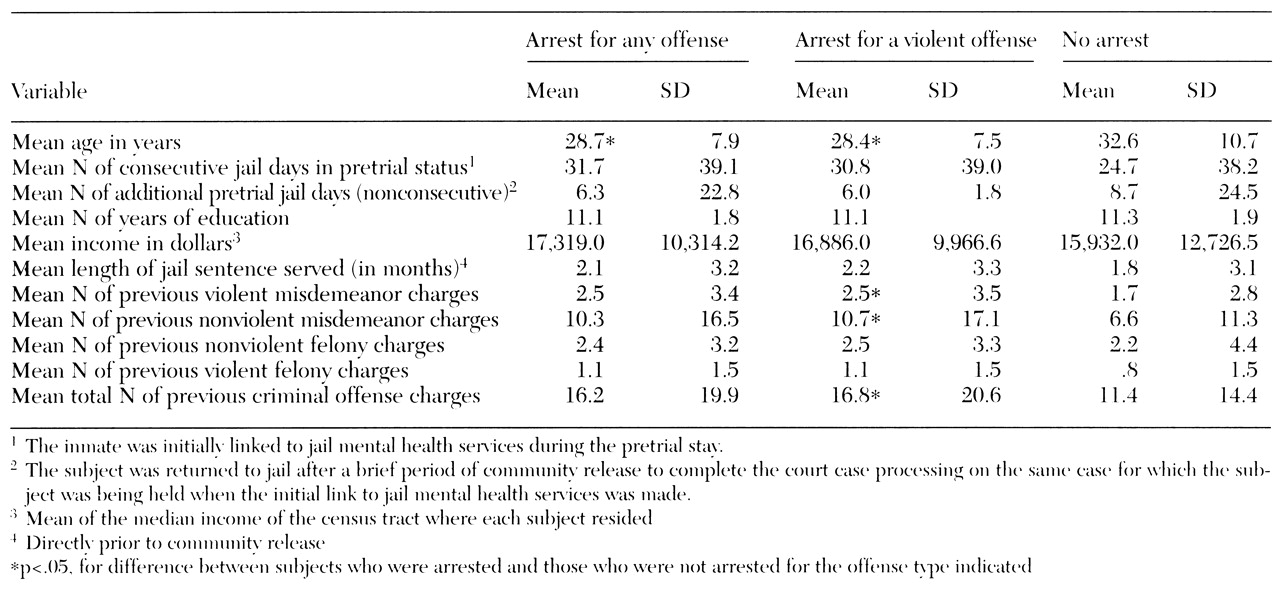

As shown in

Tables 2 and

3, subjects who were nonwhite, unemployed, and younger were significantly more likely than other subjects to be rearrested for any offense. Subjects were significantly more likely to be rearrested for a violent offense if they were younger, were nonwhite, did not have an affective disorder, had a personality disorder, and had a more extensive criminal history. These differences in rearrest by age, race-ethnicity, employment status, and previous criminal record are also found in the general population (

14).

Subjects who received jail case management were equally as likely as subjects who received none to be arrested for any offense (72 percent and 72 percent, respectively) or a violent offense (65 percent and 67 percent, respectively). However, recipients of community case management were significantly less likely than nonrecipients to be arrested for either any offense (60 percent versus 77 percent; χ2 =7.561, df=1, p<.01) or a violent offense (52 percent versus 71 percent; χ2 =8.512, df=1, p<.05).

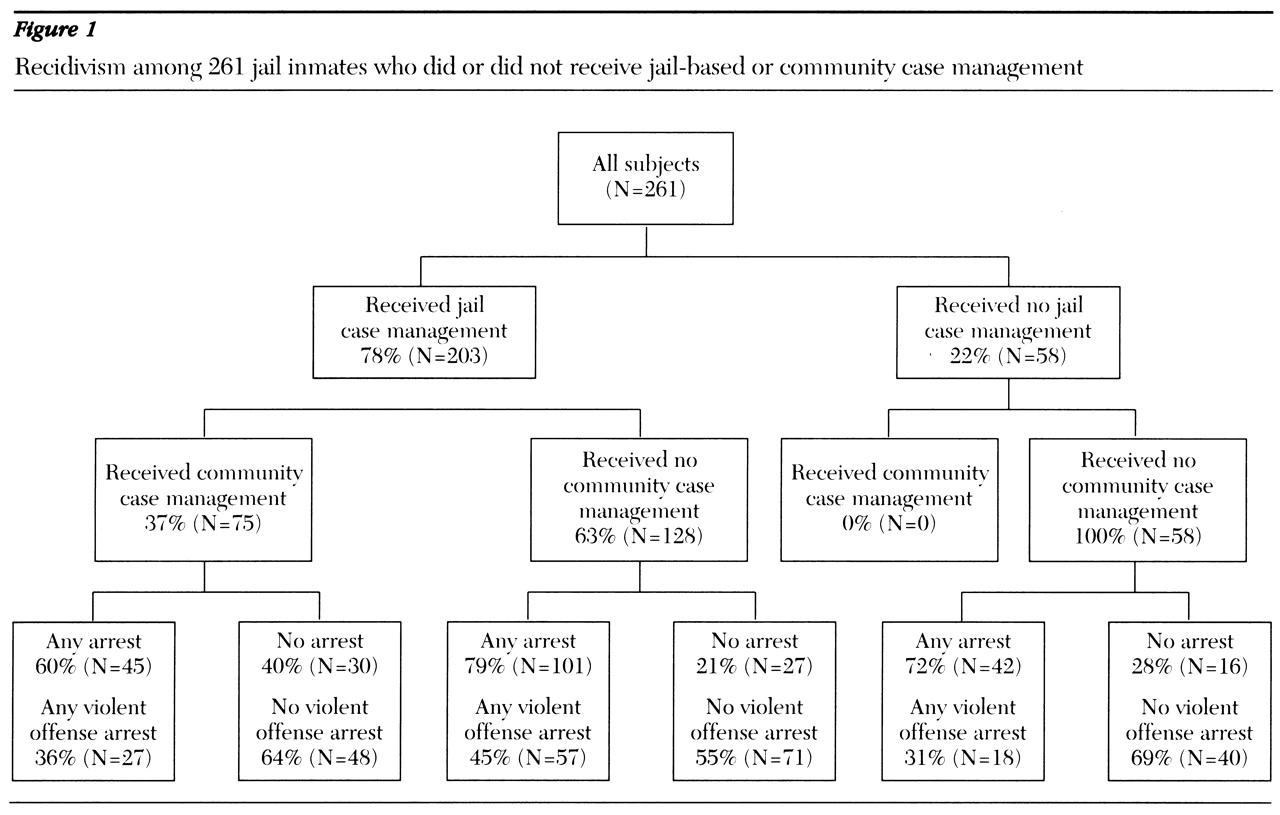

Figure 1 shows the recidivism of the subjects categorized by whether they received case management in jail and whether they subsequently received case management in the community. A significant association was found between receipt of jail case management and receipt of community case management (χ

2 =30.069, df= 1, p<.001).

Figure 1 shows that only subjects who received jail case management subsequently received community case management. As noted above, a significant association was also found between receipt of community case management and avoidance of rearrest. Subjects who received community case management were less likely to be rearrested than subjects who received no case management.

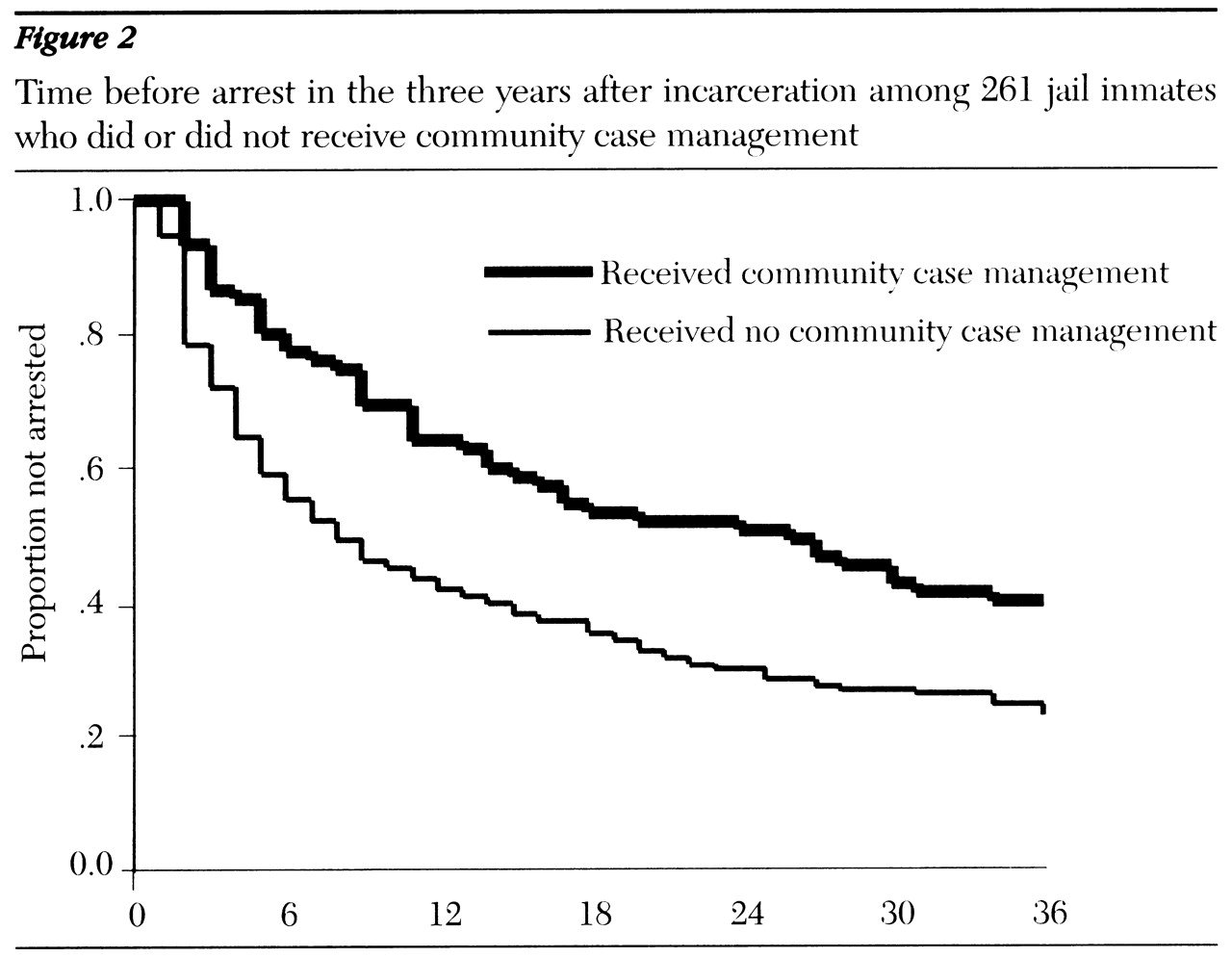

Not only were recipients of community case management less likely to be arrested but they also remained in the community longer before rearrest than subjects who received none (mean of 21 months in the community versus 14 months; F=12.369, df=1, p<.001).

Figure 2 shows the survival rates of subjects categorized by whether they received community case management. Survival rates reflect the proportion of subjects not yet arrested at each month after release. The figure shows clearly that the relationship between receipt of community case management and first arrest was strongest during the first year, after which approximately equal proportions of recipients and nonrecipients were arrested for the first time.

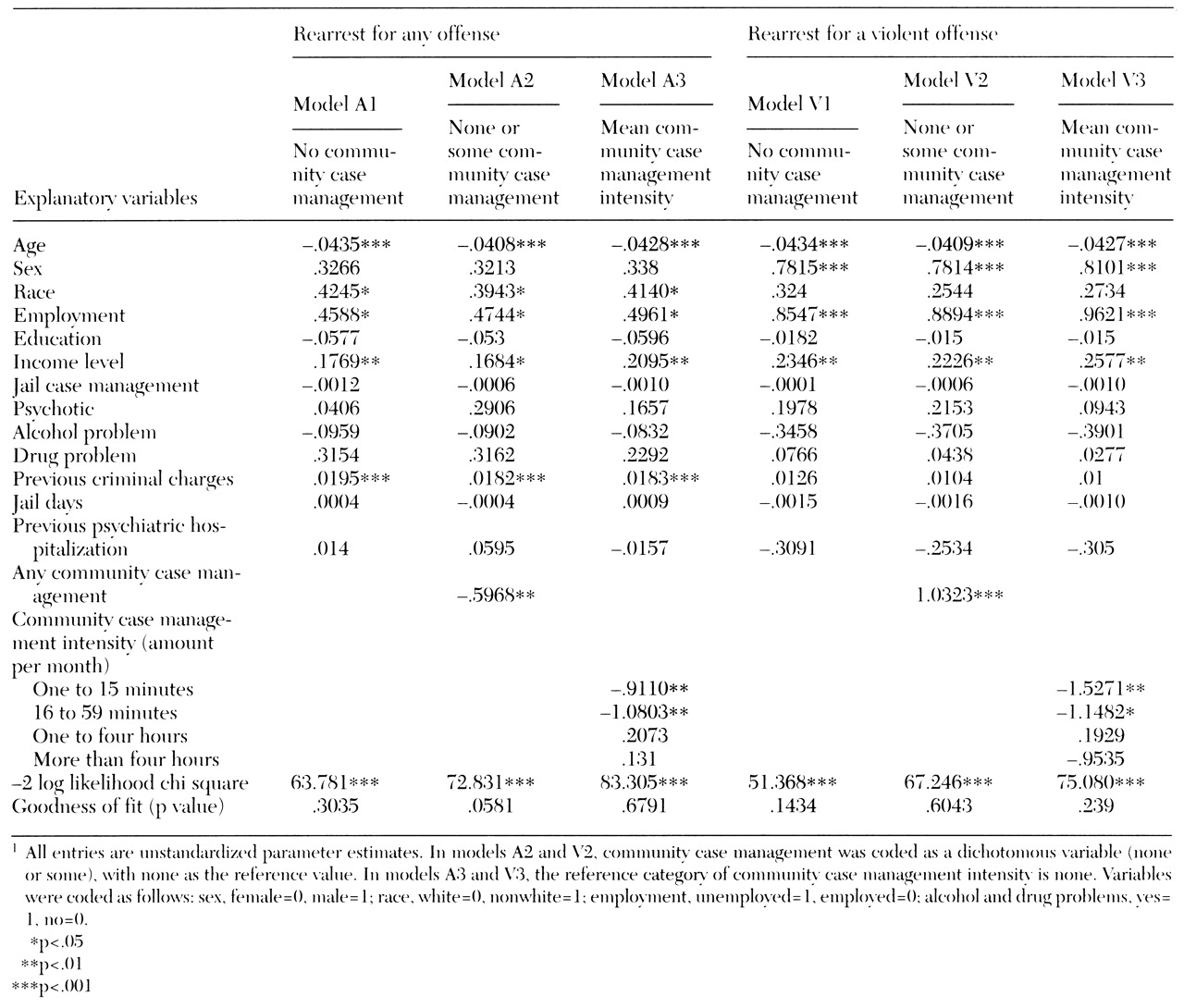

Three logistic regression models were computed in the event history analysis, which is shown in

Table 4. In model 1 the community case management variable was excluded. In model 2 community case management was included as a dichotomous variable (any case management versus no case management). In model 3 the intensity of community case management (mean amount received per month) was entered as a categorical variable. Models A1, A2, and A3 all include rearrest for any offense. Models V1, V2, and V3 are limited to rearrest for a violent offense.

Model A1, which included 911 subjects but excluded the community case management variable, fit the data well, as shown in

Table 4 by the significance of the -2 log likelihood chi square test and the goodness of fit statistic (see Yamaguchi [21] for a full discussion of significance tests appropriate to event history analysis). The variables age, race, employment status, income level, and total charges in the criminal history were significantly related to the odds of rearrest for any offense. These same variables remained significant whether or not community case management was added to the analysis of arrest for all offenses in models A2 and A3 and for violent offenses in models V1, 2, and 3.

Model A2 also fit the data well. Introducing the variable of any community case management in model A2 significantly added to the explanatory power of the original variable set. The difference between -2 log likelihood chi square values of model A2 and model A1 is 9.050 (df=1, p<.05). Furthermore, receiving community case management was associated with a 45 percent decrease in the probability of rearrest.

Model A3, which included intensity of community case management as a categorical variable, was also a good fit. Including this variable added significant explanatory power to model A1. The difference between -2 log likelihood chi square values of model A3 and model A1 is 26.425 (df=4, p<.001). The odds of rearrest were less for subjects receiving either one to 15 minutes or 16 to 59 minutes of case management a month than for subjects who received none. However, receipt of more than 60 minutes a month of community case management did not further reduce the likelihood of recidivism.