Medication compliance has become a focus of increasing concern in the treatment of psychiatric disorders in recent years. With the growing fiscal pressure to reduce reliance on hospital treatment, to shorten hospital stays, and to reduce the intensity of outpatient treatment (

1), contact between clinicians and patients may become increasingly restricted. As a result, opportunities to explain to patients the value of pharmacotherapy in psychiatric treatment and to encourage medication compliance may become more important than ever before. Thus information about factors that influence compliance and methods for facilitating optimal use of medication are especially important.

The difference between the efficacy of neuroleptic medications in carefully designed clinical trials and the effectiveness of these drugs in ordinary practice can be attributed largely to the less rigorous manner in which patients take medications—that is, partial compliance—in the typical outpatient treatment setting (

2). Advancements in the treatment of psychiatric disorders are limited by discontinuation of medications and partial compliance, which steal power from even the most beneficial medications. Noncompliant patients' lack of treatment response can lead to their being switched from one drug to another, with little success because they do not take the drug as prescribed.

The psychiatric literature offers many theoretical explanations for why patients do not follow prescribed regimens. Unfortunately, most reports are either primarily descriptive or use unreliable methods of assessing compliance, such as patients' self-reports. Few studies adequately quantify the problem.

In this paper we review the literature on quantitative studies of medication compliance in psychiatric treatment. The purpose of the review is to evaluate estimated rates of compliance with psychopharmacologic treatment and compare them with rates of compliance in other areas of medicine.

Methods

We used MEDLINE to search the literature for the years 1975 to 1996. Key words used for the search were compliance, adherence, mental health, psychosis, schizophrenia, depression, and mood. Additional reports were selected from references in the papers identified in the search. Papers were included in our review if they reported studies in which medication compliance was evaluated and tabulated (including surveys and clinical trials with specific interventions) and if the method of assessing compliance was described. Meta-analyses of studies of compliance were considered separate resources.

Only ten reports about antidepressant medications and 26 reports about antipsychotic medications provided enough information to be included in the review. For comparison, we used data on rates of compliance with medication prescribed for a range of physical disorders. The data were drawn from a previous survey of 12 studies that used microelectronic monitoring of compliance, which is described below (

3).

Four methods are commonly used to assess compliance with medication regimens. Each method has advantages and disadvantages.

Direct questioning of patients in interviews or by questionnaire, followed by clinicians' judgments about the accuracy of patients' responses, is a simple and rapid method but proved to be inadequate for evaluating medication compliance (

4).

A count of the number of pills, tablets, or capsules a subject returns to researchers at the end of a study period constitutes a simple and rapid assessment of medication compliance. However, patients who want to avoid showing that they missed doses may not return unused medication. Pill counts provide accurate compliance estimates for compliant patients, but the accuracy diminishes among patients with lower compliance rates (

5,

6). Prescription renewals also can be used as a proxy indicator of compliance based on usage, making it convenient for computer analysis of refill rates. However, these analyses require that patients receive all refills from a single source and that the system records all changes in dose or drug.

Therapeutic drug monitoring, which involves testing the levels of a drug in the blood or urine, is invasive and requires costly laboratory analyses. However, blood levels can be misleading because rapidly cleared drugs achieve drug serum concentrations near target levels after several doses. Taking doses for a few days before a test raises drug levels reasonably close to target. These "spot levels" do not reflect compliance over a long period, although a blood level of zero clearly shows no recent drug ingestion (

4). Urine tests provide evidence of ingestion of some medication at some recent time (

4).

Microelectronic monitoring systems, a novel approach to assessing patient dosing, are now considered the best measure available for compliance assessment (7—

9). In this method, a special bottle cap with a microprocessor is used to record data. The cap is engineered to record the date and time of every bottle opening. When the cap is connected to a computer, data are usually displayed as a calendar showing the number of container openings each day and the time of each bottle opening. The data can be shown to the patient as part of a program to enhance compliance in which the clinician would point out lapses and make suggestions about how to remember to take medication.

However, microelectronic systems are expensive and require computer software to view and analyze the data and are thus largely restricted to research. Although the results can be misleading if the patient opens the bottle but does not ingest the medication, such false recordings are presumed to be rare, based on previous studies (

9). In addition, recent data are lost if the patient loses the bottle. (Previous data are stored on the computer.)

Results

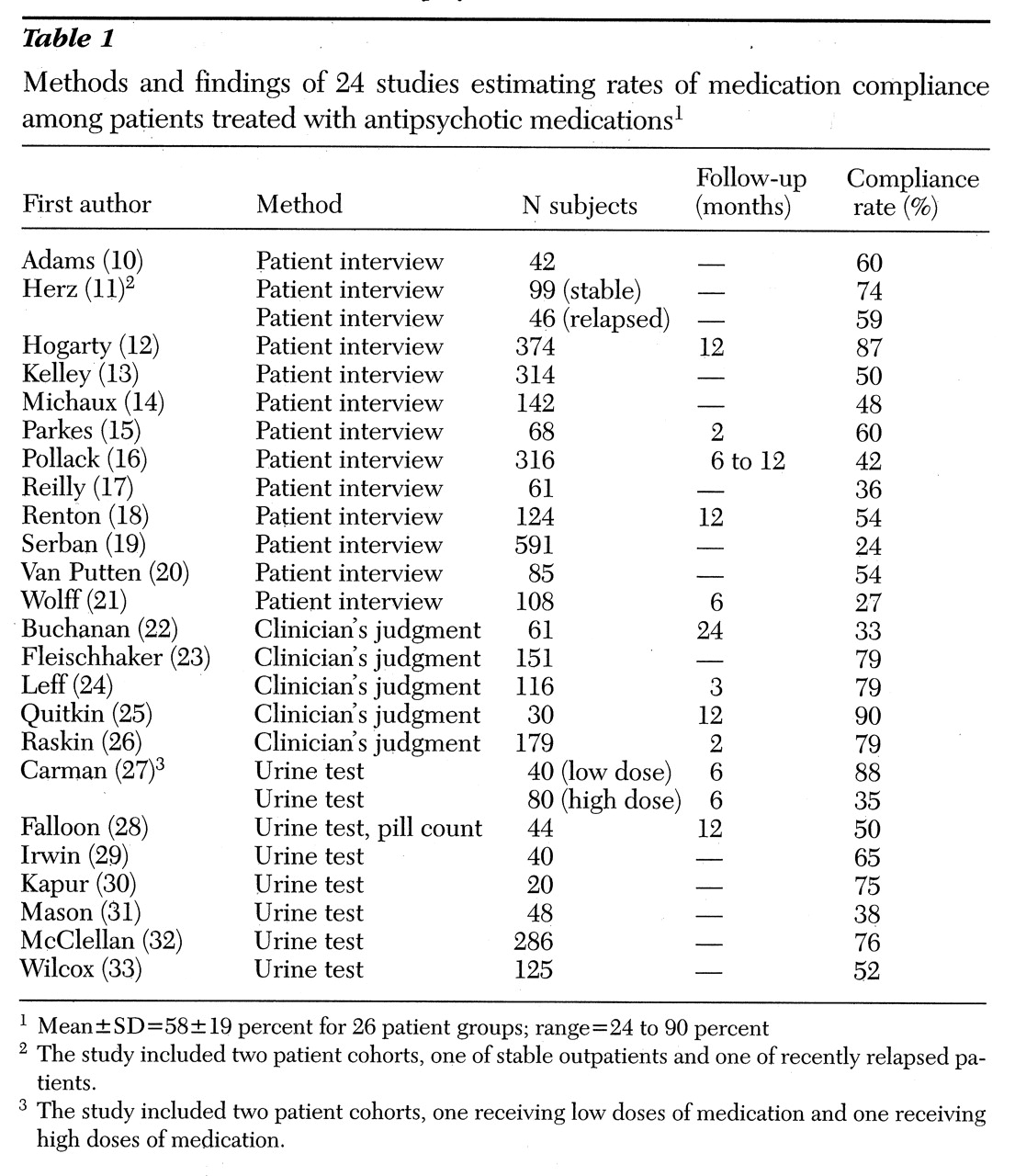

Compliance with antipsychotic medications

Table 1 lists 24 reports (that include 26 patient groups) from which a compliance rate for antipsychotic medication could be determined (10-33). The methods for compliance assessment used in the studies were patient interview, clinician assessment, urine or blood marker, and pill count (number of tablets remaining). Most or all patients included in the studies had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Rates of compliance differed by methodology and the number of patients evaluated, which ranged from 20 to 591. The mean level of compliance for antipsychotic medications among all 26 groups was 58±19 percent, with a range from 24 to 90 percent.

Thirteen papers reported on studies that used patient interviews. The mean rate of compliance in these studies was 52±17 percent, with a range from 24 to 87 percent. Thus the results for the studies using patient interviews, a less accurate method, skewed the overall rate.

The five studies that used clinician assessments found higher compliance (mean±SD=72±20 percent, with a range from 33 to 90 percent). Urine tests were used in seven studies, one in which they were supplemented by pill counts. The compliance rate in these studies was 60±18 percent, with a range from 35 to 88 percent. Thus a wide range of rates have been reported for compliance with antipsychotic medication.

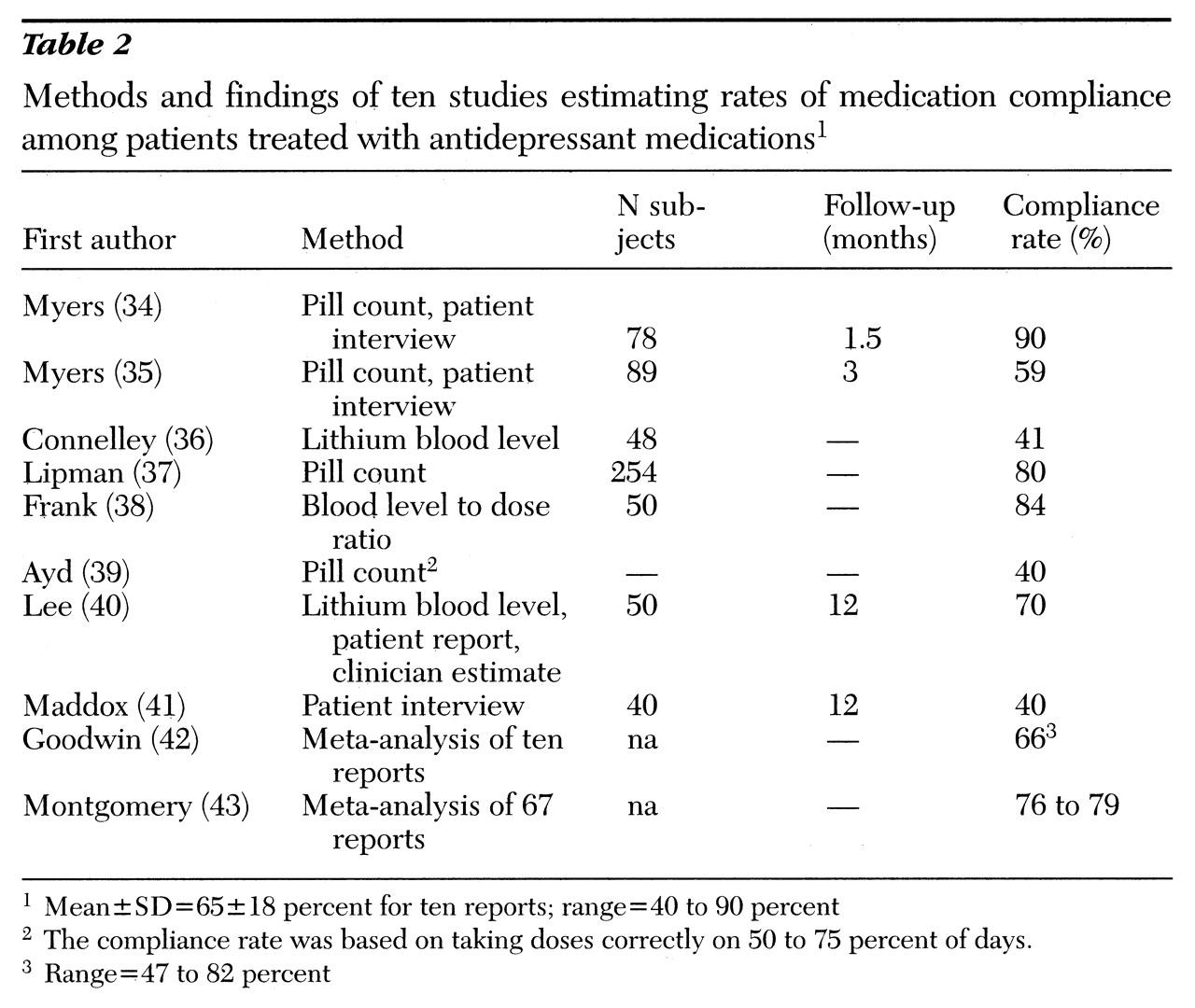

Compliance with antidepressant medications

Table 2 lists ten reports from which a compliance rate for antidepressant medication could be determined (34-43). These reports are largely from clinical trials that included formal means for assessment of medication compliance. Pill counts and lithium blood levels were supplemented by patient interviews.

Results from two meta-analyses were included in the review. Goodwin and Jamison (

42) surveyed ten reports with a mean rate of compliance of 66 percent (range=47 to 82 percent). In an evaluation of 67 studies, Montgomery and Kasper (

43) found a mean compliance rate of 79 percent.

In the eight individual studies we reviewed, the number of subjects ranged from 40 to 254. The mean± SD rate of compliance was 63±18 percent, with a range from 40 to 90 percent, similar to the findings from meta-analyses.

Overall compliance for antidepressant medications was 65±18 percent, with a range from 40 to 90 percent, including all reports.

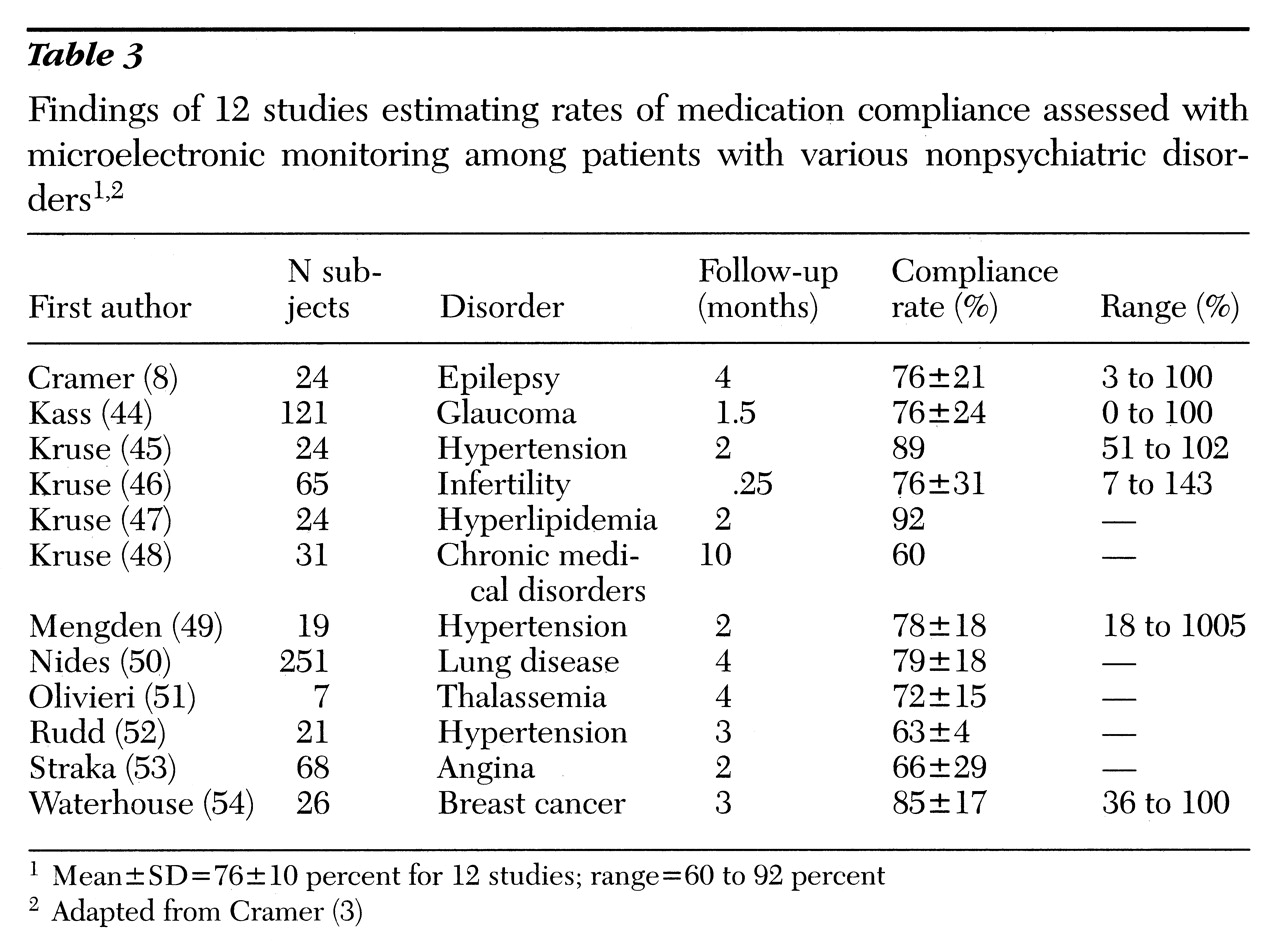

Compliance with medication for physical disorders

Before concluding that patients with psychiatric disorders have unusually poor compliance rates, we should consider comparable data from other populations (

3).

Table 3 lists data from a survey of 12 recent studies that used microelectronic systems to monitor dosing among patients with various physical disorders (8,44-54). Subjects in those studies took about 76±10 percent of doses as prescribed, with means ranging from 60 percent to 92 percent. However, compliance rates for individuals who participated in the studies ranged from 0 to 143 percent (rates over 100 percent indicate that the subject took more than the prescribed doses), showing a broad range of compliance with a variety of treatments for physical disorders.

Discussion

We found that the ranges of medication compliance rates reported for populations with psychiatric illness—24 to 90 percent for patients treated with antipsychotic medication and 40 to 90 percent for patients treated with antidepressants—were much wider than those reported for patients with physical disorders in studies using microelectronic monitoring, 60 to 92 percent. These differences may be attributed partly to the various definitions of compliance used in the studies and partly to the design and methods of assessment.

Thus it is not clear what differences in compliance might exist between populations with psychiatric illness and those with physical disorders. No studies of psychiatric patients that have used microelectronic monitoring or other methods of long-term quantitative assessment have been reported. However, an overview of the extensive literature on medication compliance found no differences in compliance rates between populations with physical disorders and those with psychiatric disorders (

55).

Despite the potential for severe psychiatric or medical consequences, people do not consistently take the prescribed amount of medication. However, our review suggests little difference in rates of compliance among populations prescribed a variety of medications for various psychiatric and physical disorders.

The studies of patients with physical disorders included in our review used a system of continuous microelectronic monitoring that provided compliance data over a follow-up period. The studies of antidepressant treatment we reviewed were clinical trials in which pill counts were used to provide a quantitative, systematic assessment of compliance. Pill counts tend to overestimate compliance compared with microelectronic monitoring, with closest approximation among subjects with higher rates of compliance (

5,

6). Of the three groups of studies we reviewed, those that examined treatment with antipsychotic medication had the least quantitative study designs. Most of these studies reported rates of compliance based on patient interviews or clinicians' estimates.

Several studies show that the problem of poor initial compliance is compounded by the continued decline in compliance over time. Maddox and associates (

41) found that only 40 percent of 46 patients started on an antidepressant continued to take it for a year. In a study of 40 patients with mood disorders, relapse was significantly associated with poor compliance (

56). In another study, six of 12 patients who had relapses were identified as noncompliant, but only two of 28 patients without a recurrence were noncompliant (p<.04). Sullivan and associates (

57) compared estimates of medication compliance with rates of hospitalization in a study of 101 patients with mental illness. Overall, poor compliance with medication was a significant factor in the need for rehospitalization (odds ratio of 8.2). In a retrospective review of 225 relapses among patients with schizophrenia, Razali and Yaha (

58) found that only 27 percent of patients had good compliance with medication.

Many studies show that compliance is erratic (

8,

10,

39,

59,

60). For example, patients with epilepsy in a long-term follow-up study that used continuous microelectronic monitoring were more compliant than usual (86 percent versus 75 percent, p<.01) during the week before and the week after a clinic visit, suggesting that compliance was influenced by anticipation of the visit and reinforcement of the need for treatment during the visit (

59). However, compliance was significantly lower one month after the visit (67 percent, p<.05), suggesting reduced vigilance about the daily regimen as the time since a medical visit lengthened. In addition, microelectronic monitoring revealed that days with no dosing could be matched to a seizure occurring the following day.

Blackwell's 1996 paper (

55) reviewed the literature published over the past 25 years on medication compliance for physical and psychiatric disorders. His eloquent analysis of social history as a context for medical issues was based on about 12,000 publications, half of them review articles and half reporting original data. The literature suggesed that good compliance is related to patients' satisfaction, continuity of care, and acceptance of the need for treatment. Poor compliance was thought to be common among patients with chronic, asymptomatic disorders and was associated with complex treatment regimens, adverse effects, and social dysfunction. A more pragmatic view has been offered by Urquhart (

61), who developed the concept of "forgiving" medications—those that continue to provide a therapeutic effect even when a dose is late or forgotten.

The effects of strategies aimed at improving compliance are unlikely to differ significantly in different patient populations. The simplest techniques to help patients enhance their medication-taking behaviors are based on the use of cues that establish a daily pattern for the individual (

62). Using a specific cue such as a specific time of day, a meal, or other daily habit helps reinforce the behavior of taking a dose of medication as part of a daily routine. We are currently engaged in research to evaluate the effectiveness of simple cues and other direct feedback techniques for patients with severe mental illnesses.