Setting

The Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (GHC) is a large staff-model HMO that provides comprehensive care on a capitated basis for approximately 400,000 persons in western Washington. Most members receive coverage through employer-subsidized plans. Approximately 10 percent of enrollees are covered by Medicare, and 7 percent are covered by Medicaid or by Washington's Basic Health Plan, a state program for low-income residents. The sociodemographic characteristics of the HMO enrollees reflect those of people living in the Seattle metropolitan area except that enrollees have a slightly higher level of education and fewer individuals are at the low and high extremes of income.

Primary care for adults is provided by approximately 360 primary care physicians, most of whom are board certified in family medicine. Outpatient specialty mental health services are available through physician referral or self-referral to six GHC mental health clinics staffed by approximately 20 psychiatrists and 90 nonphysician providers. Specialty mental health clinics emphasize short-term individual psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and group therapy. Typical coverage arrangements for outpatient care provide for unlimited psychiatric medication management visits (subject to copayments of $5 to $10 a visit) and ten to 20 outpatient psychotherapy visits (subject to copayments of $10 to $20 a visit). No referral or authorization is needed for specialty mental health care, and primary care physicians have no financial incentives to limit the use of mental health services.

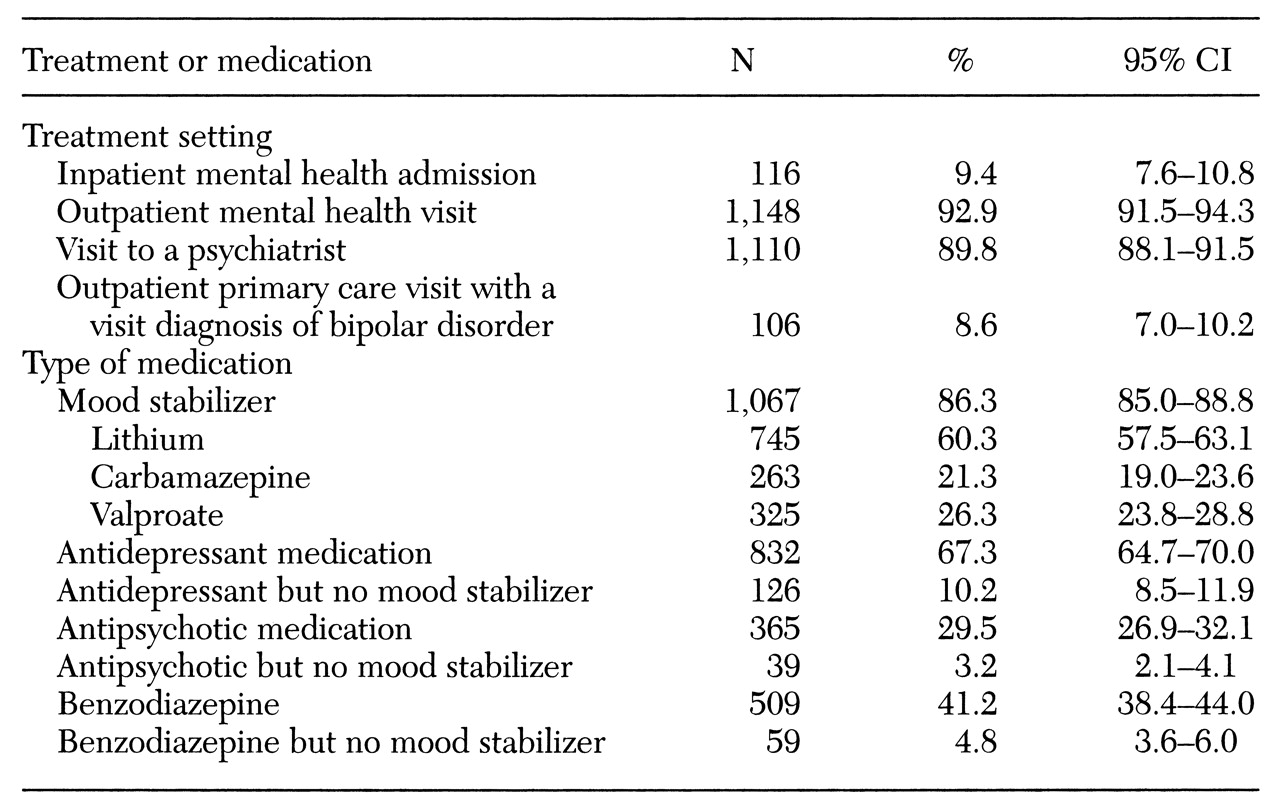

Most inpatient and partial hospital psychiatric care is provided at facilities contracted to provide inpatient care at a fixed daily charge. Typical GHC coverage arrangements for inpatient care provide 14 to 30 days of treatment per calendar year, with coinsurance rates of 10 to 20 percent. Most enrollees have a prepaid drug benefit as part of their enrollment, and more than 95 percent of prescriptions filled by members, including those for antidepressant drugs, are filled at GHC pharmacies (

15).

Subjects

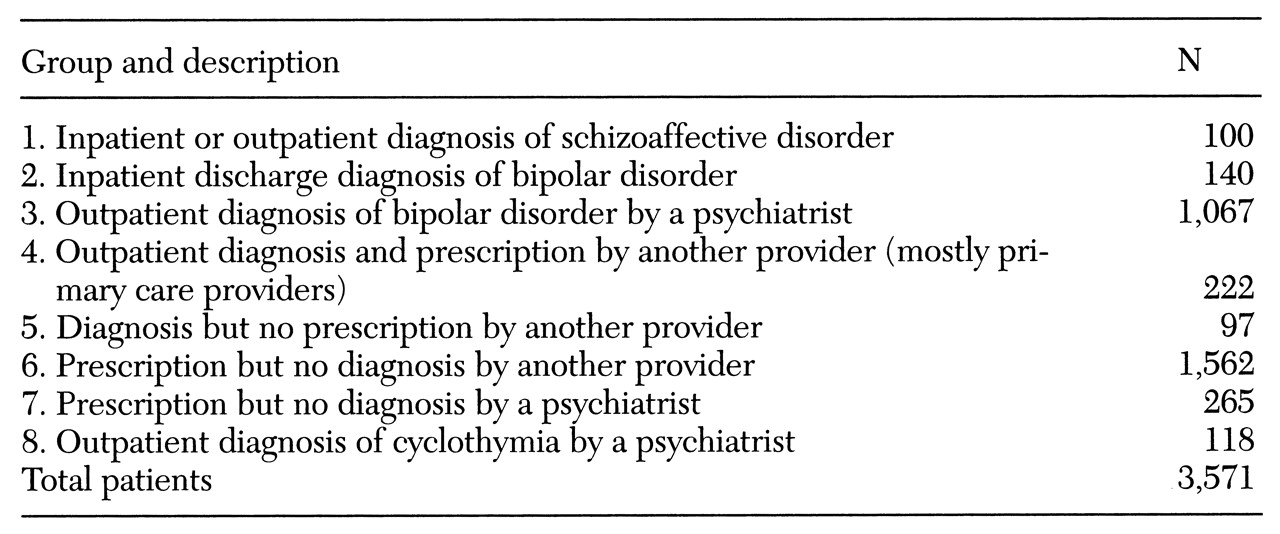

Potential subjects were all 294,284 persons who were receiving services from GHC providers or covered by GHC health plans between July 1, 1995, and June 30, 1996. Computerized records of inpatient diagnoses, outpatient visit diagnoses, and outpatient prescriptions for mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate) were used to identify all enrollees meeting any of the following criteria during the study period: any inpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder (type I or type II), schizoaffective disorder, or cyclothymia; any outpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder (type I or type II), schizoaffective disorder, or cyclothymia; any outpatient prescription for a mood stabilizer, excluding prescriptions from neurologists or prescriptions associated with a diagnosis of seizure disorder. As shown in

Table 1, we organized the initial cohort of 3,571 patients into eight groups. These groups were hierarchically arranged so that if an individual met criteria for group 1, for example, he or she did not appear again in a lower group.

To examine the validity of this casefinding method, two psychiatrists (JU and GS) reviewed a random sample of 225 of the 3,571 outpatient medical records in two mental health and two primary care clinics. Specifically, we attempted to see if we could confirm the diagnosis of bipolar disorder using chart data or if there was some other indication for the use of a mood stabilizer such as the augmentation of antidepressant medication in unipolar depression. Through the use of structured chart abstraction forms and applying

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (

16), subjects were classified as likely bipolar disorder, as having insufficient evidence for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, or as having a clear other indication for the use of a mood stabilizer.

We did not expect to confirm bipolar diagnoses in all cases. In some cases, the history of manic episodes was in the distant past, and we expected a moderate rate of insufficient evidence in the chart, especially for bipolar patients who were stable on their medication regimen.

Based on these chart reviews, we eliminated from the final sample all patients in groups 5 and 6 because it was ascertained in the validity check that more than 50 percent of patients in these categories did not appear to have bipolar disorder. Both of these groups had a large number of subjects for whom sufficient evidence of bipolar disorder was not documented in the chart or who were receiving mood stabilizers, particularly anticonvulsants, for indications other than bipolar disorder, such as for behavior problems in dementia or chronic pain syndromes.

The validity check showed that group 7 contained a large number of subjects for whom limited documentation of bipolar symptoms existed in the chart or who were receiving mood stabilizers for other indications, such as lithium used to augment antidepressant medications. We therefore used an additional strategy to clarify the diagnoses of the 265 subjects in this group. We asked all 15 GHC psychiatrists who had treated patients from this group to clarify whether these patients had bipolar disorder or if they had another diagnosis such as schizoaffective disorder, cyclothymia, or another mental disorder. Based on the diagnoses assigned by the psychiatrists, 33 patients from group 7 were reassigned to group 3.

We chose to accept all patients in groups 1 to 4 and group 8 for our final sample. In group 1, the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder was generally confirmed by chart review, and only one subject had other indications for the use of mood stabilizers. In groups 3 and 4, the diagnoses were generally confirmed by chart review, and no cases of other indications were found.

The resulting study sample included 1,680 subjects—1,462 patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 118 patients with a diagnosis of cyclothymia, and 100 patients with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder.

Treated-prevalence rates and statistical analyses

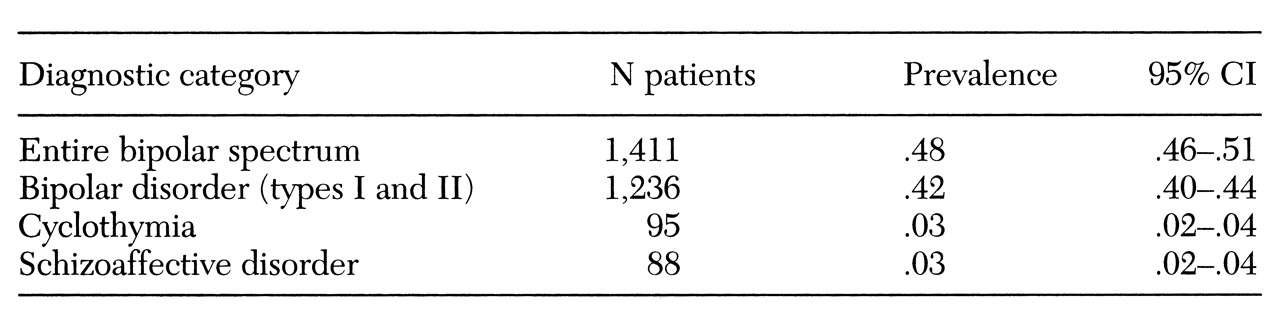

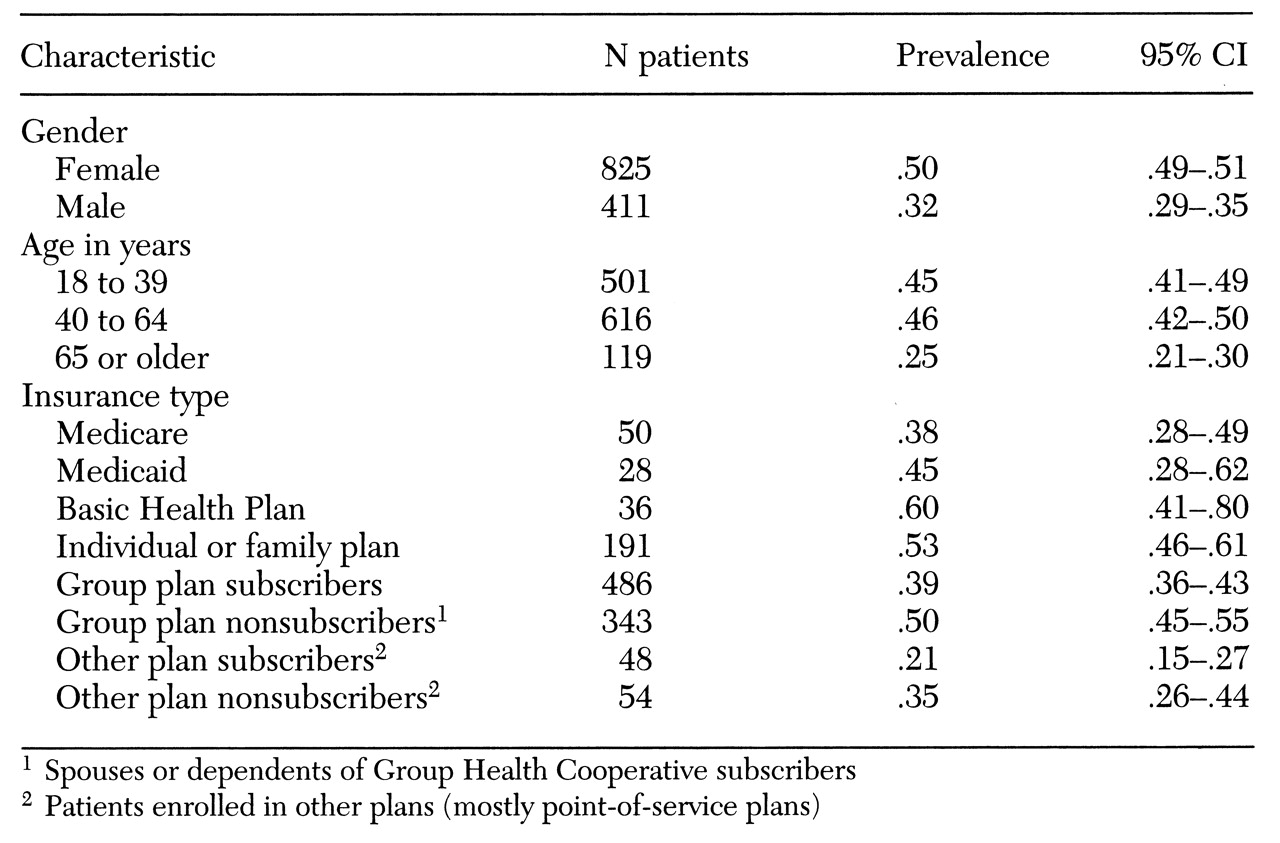

Treated-prevalence rates were calculated by dividing the number of cases in each diagnostic category—bipolar-spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder types I and II, cyclothymia, and schizoaffective disorder—by the total number of persons in each category who were enrolled at GHC on January 1, 1996, the midpoint of our study period. The analyses of treated prevalence were restricted to enrollees age 18 and older, a total of 1,411 subjects.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 7.1 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the treated prevalence of patients in various subgroups.