Recently, after two psychiatric patients died of heatstroke during a heat wave in California, their board-and-care facility was ordered to pay $1.2 million because it had not warned the patients that heat-related illness was a risk of antipsychotic medications (

1). Heatstroke is rare and often not recognized. This study examined deaths associated with heat waves, because they are not rare and can easily be recognized. Although heatstroke contributes less than 5 percent to the increased mortality during heat waves, the age and sex distribution and many risk factors, including poverty, age, lack of air-conditioning, diabetes, and alcoholism, are the same in heatstroke and in deaths during heat waves (

2,

3,

4).

Because of unexpected deaths during heat waves in New York State psychiatric hospitals in the 1970s, major preventive measures were instituted beginning in 1979. They included installation of air-conditioning, close monitoring of medications, and staff training in prevention and recognition of heatstroke. The study reported here consisted of three analyses examining whether psychiatric patients were at increased risk of dying during heat waves compared with other times and compared with the general population. Although the data were collected before 1985, the findings are as relevant today as they were when the data were collected. They show that psychiatric patients are at increased risk of dying during heat waves and that such deaths are preventable.

Methods

A heat wave was defined as a period of three or more days with a maximum temperature of 89 degrees Fahrenheit or more, with the day following the high-temperature days included in the heat-wave period. The extra day was included because deaths related to heatstroke often occur one day after a heat wave. Control periods were the two periods closest to but at least a week before or after the heat wave when the temperature did not rise above 85 degrees Fahrenheit. The control periods covered the same days of the week as the associated heat-wave period.

The first analysis compared all the deaths during heat waves with deaths during control periods from 1950 to 1984 in one New York State psychiatric hospital located 25 miles from New York City. The relative risk of death during various five- and ten-year periods was compared. Relative risk was calculated by dividing the mean number of deaths during heat waves by the mean number of deaths during control periods.

The second analysis compared the number of deaths among patients in ten state hospitals within 50 miles of New York City with deaths in the general population in New York City for 1971-1984 directly and by relative risk. Data on age and sex of the deceased persons were also compared. In addition, data for the years before institution of preventive measures in New York state hospitals (1971-1979) and after (1980-1984) were compared. For the New York City population, data from the 1970 and 1980 censuses were used. For the psychiatric hospitals the population in July of each year was used.

The third analysis examined deaths of psychiatric patients during heat waves by psychiatric diagnosis at death, cause of death, length of hospitalization, race, age, and sex.

Results

Between 1950 and 1984 there were 72 heat waves lasting from three to 18 days (mean length of 4.4 days), with maximum temperatures ranging from 91 to 107 degrees Fahrenheit (mean of 92.2 degrees). The heat waves occurred from May to September; the mean time of occurrence was the last week in June. During all heat waves the relative risk of death overall was increased. It was highly correlated with the average maximum temperature, except during the fourth heat wave in a year with four heat waves and during the third heat wave in two of the five years with three heat waves. The lack of an increase during those heat waves was presumably due to acclimatization.

The increased risk of death during all first and second heat waves in a year (relative risk [rr]=1.24 and 1.12, respectively) confirms the usefulness of the definition of heat wave used in this study. The relative risk increased significantly as the heat waves lengthened to six days and then decreased.

In the analysis of data from the single state hospital 25 miles from New York City, significantly more patient deaths occurred during heat waves than during control periods, except during 1977-1984. The overall relative risk between 1950 and 1984 was 1.36 (N=521 deaths during heat waves). Relative risk was 1.36 (N= 106) for the years 1950-1954, before the introduction of the modern psychotropic drugs. During 1955-1964 the relative risk was 1.29 (N=252), and during 1965-1974, it was 1.52 (N=127). Relative risk was highest at 1.74 (N=20) in 1975-1979. It was 1.19 (N=16) in 1980-1984. Interpretation is complicated by the decrease in the hospital population from 8,000 in 1955 to 1,500 in 1984.

The second analysis showed differences between psychiatric patients and the general population that were unrelated to heat waves. During the control periods, death rates in the hospitals were about double those in the general New York City population but were approximately the same for male and female patients by age group. In the New York City population, death rates of males were about twice those of females.

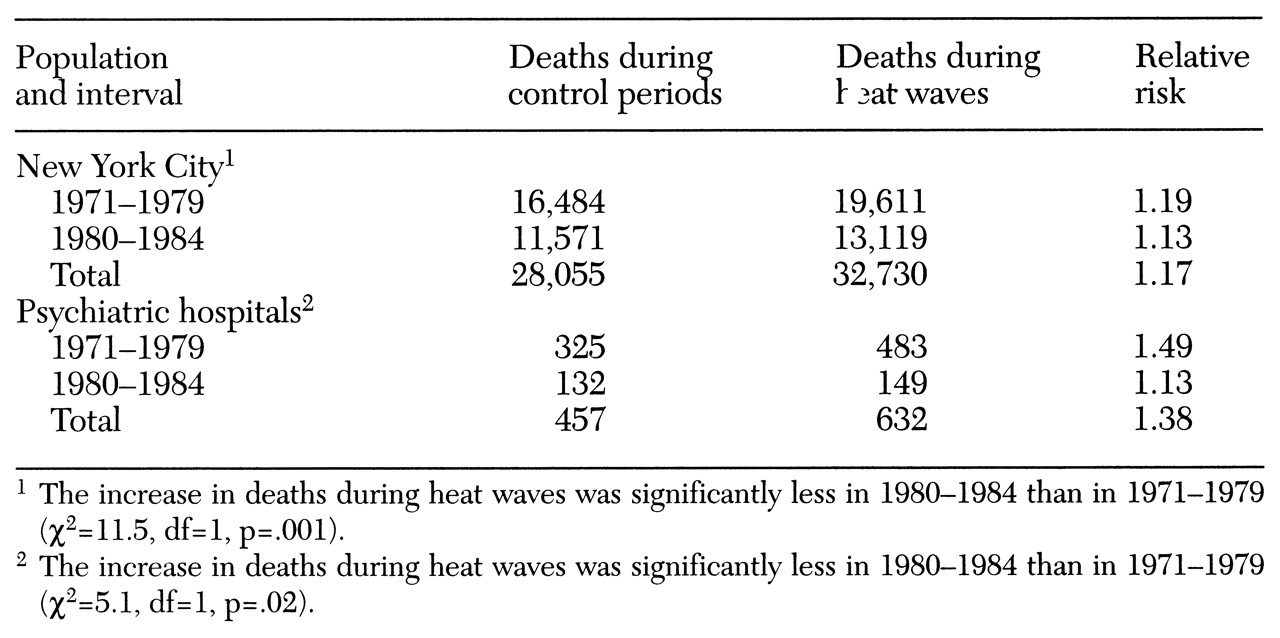

The total number of deaths and relative risk of death during a heat wave in the psychiatric hospitals and in the New York City general population from 1971-1979 and from 1980-1984 are shown in

Table 1. Highly significant increases in risk of death occurred in both populations over the total period from 1971 to 1984, but the increase was much greater—twice as high—among patients in psychiatric hospitals (rr=1.38) than in the general New York City population (rr=1.17).

Relative risk dramatically declined in psychiatric hospitals from 1.49 in 1971-1979 to 1.13 in 1980-1984. In New York City the relative risk decreased from 1.19 to 1.13 during the same periods. Thus in 1980-1984 relative risk was equal for the two populations.

During 1971-1984 relative risk among female patients in the hospitals was 1.41 (higher among younger female patients) and 1.34 among male patients. In the New York City population the relative risk among females was 1.21 (higher among older females) and 1.15 among males. The risk of death of females compared with males was significantly higher during heat waves than during the control periods only in the New York City population. Surprisingly, patients over age 60 in the hospitals were not at significantly greater risk (rr=1.39, compared with 1.35 for patients under age 60). However, persons over age 60 in the New York City population were at greater risk (relative risk=1.20, compared with 1.11 for persons under age 60).

The third analysis, which examined risk of death during heat waves associated with psychiatric diagnosis and other clinical and demographic characteristics, showed that patients with dementia were the only group in which the number of deaths during heat waves was significantly different from the number during the control periods. Surprisingly, fewer deaths of patients with dementia occurred during heat waves (rr=.8). Patients were at greatest risk of death during heat waves during their first month in the hospital (rr=2.1); lower levels of relative risk, ranging from 1.1 to 1.4, were present at all other intervals after admission. No significant differences were found between risk during heat waves and control periods by cause of death or by race.

Discussion and conclusions

The most important finding was that hospitalized psychiatric patients, who already had higher death rates than the general population (

5), had twice the relative risk of dying in a heat wave. The incidence of death among psychiatric patients was four times that in the general population.

Psychiatric patients were also at increased risk before the introduction of antipsychotic medications, suggesting that psychiatric illness itself contributes to deaths during heat waves. The increased risk may be due to a physiological vulnerability, as the neurotransmitters that are involved in thermoregulation are also involved in the disease processes of schizophrenia and depression (

6,

7). The increased risk may also be due to increased agitation, which may be why higher risk is associated with the first month in the hospital. Other possible explanations include lack of air conditioning, inadequate care, and patients' lack of understanding of the danger of excessive heat, leading them to neglect precautions such as taking off extra clothing and drinking additional fluids.

Patients' risk of death during heat waves initially went down after antipsychotic medications were introduced, but it was highest when higher doses were being used in the late 1970s. Psychotropic medication has been found to be a risk factor for heatstroke (

4). Mepazine, the most anticholinergic of all antipsychotic medications, was withdrawn from use because of case reports of heatstroke (

8). The newer medications such as clozapine and olanzapine may not be advantageous from the perspective of heatstroke prevention, as they have considerable anticholinergic effects, and clozapine is known to increase body temperature.

The age and gender differences in risk between the New York City population and the psychiatric hospital population could be explained by differences in basic living conditions. Basic shelter and care was provided to everyone in the hospitals, whereas elderly persons and women in the general population were more likely to be poor and to lack air-conditioning and medical care. The lowered risk among patients with dementia is hard to explain but may be due to the transfer out of the hospitals of patients with medical conditions that could be associated with dementia.

An encouraging and important finding is the clear reduction in risk after preventive measures were introduced in 1979. At the hospital in the first analysis, a computerized drug monitoring system was started in 1977, and the risk there was reduced to zero in that year.

However, most psychiatric patients are not in the hospital and remain at high risk as outpatients (

9). The duty to warn patients of the risks during hot weather is clear (

1), and prevention is paramount. Outpatients should be cautioned not to exercise vigorously in hot weather, to use air-conditioning (even an hour a day in a supermarket is helpful) (

4), to wear loose, light clothing, to keep out of direct sunlight, and to drink extra fluids (

10). Medication, particularly anticholinergics, should be kept to the minimum, and benzodiazepines, rather than antipsychotic medications, should be used for agitation.

Acknowledgments

The author's work was partly supported by a grant from the Rose M. Badgeley Charitable Trust at the Nathan S. Kline Institute and National Service Award 5T32MH1304340 from the Public Health Service. The author thanks D. Robert Brebbia, Tony Badalamenti, Anne Brebbia, Al Maiwald, Sol Blumenthal, Jean Lee, Chi Hwa, Denize Da Silva Siegal, and Anne-Marie Shelley.