Discussions of workforce requirements in mental health care (

1,

2,

3) have been hampered by inadequate data on the productivity of providers. Goldman and associates (

4), using a rational methodology for developing workforce requirements, concluded that a community mental health outpatient psychiatrist could manage ten new patients a week and a caseload of 165 to 323 patients, depending on the acuteness of the patients' illnesses and the level of service they required.

Their method did not consider the care provided by nonpsychiatrist professionals, whose contributions are vital to the team approach that is used by many health care facilities. Building on the work of Goldman and associates, this study used data from three Veterans Affairs mental health clinics to develop a method for determining staffing requirements. This model could help VA and other outpatient facilities evaluate their needs for professional services.

Methods

Data on patient encounters with mental health professionals at three Veterans Affairs mental health clinics for the one-year period from February 1, 1995 to January 31, 1996, were obtained from computer records. Each clinic operated as part of a nearby general medical VA clinic in one of three medium-size or large cities in northern California.

The patients in each clinic largely presented with serious axis I disorders, predominately psychotic and mood disorders. Most patients with substance use disorders were treated in other settings; thus patients with substance use problems represented a small minority of patients served in the clinics. Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder also constituted a small percentage of the total caseload.

Data for each patient included the patient's name, the treatment provider's name and profession, whether the patient was seen in group or individual sessions, and the number of "stops" generated during the year. VA defines a "stop" as any contact between the patient and a provider during a clinic visit. (A visit is defined as one outpatient's care on a given day, however many providers are seen.) The number and percentage of patients seen only by psychiatrists, seen only by nonpsychiatrists, and seen by both types of practitioners were calculated. In addition, the number of stops in which each patient was seen by either group of professionals and by both groups were calculated.

A spreadsheet that allows users to vary assumptions about workload and providers' time was used to compute workforce requirements. (The complete spreadsheet model for Lotus 1-2-3 for Windows 95 or Excel for Windows or Macintosh, with instructions for modifying assumptions to calculate the requirements for other clinics, is available from the author.)

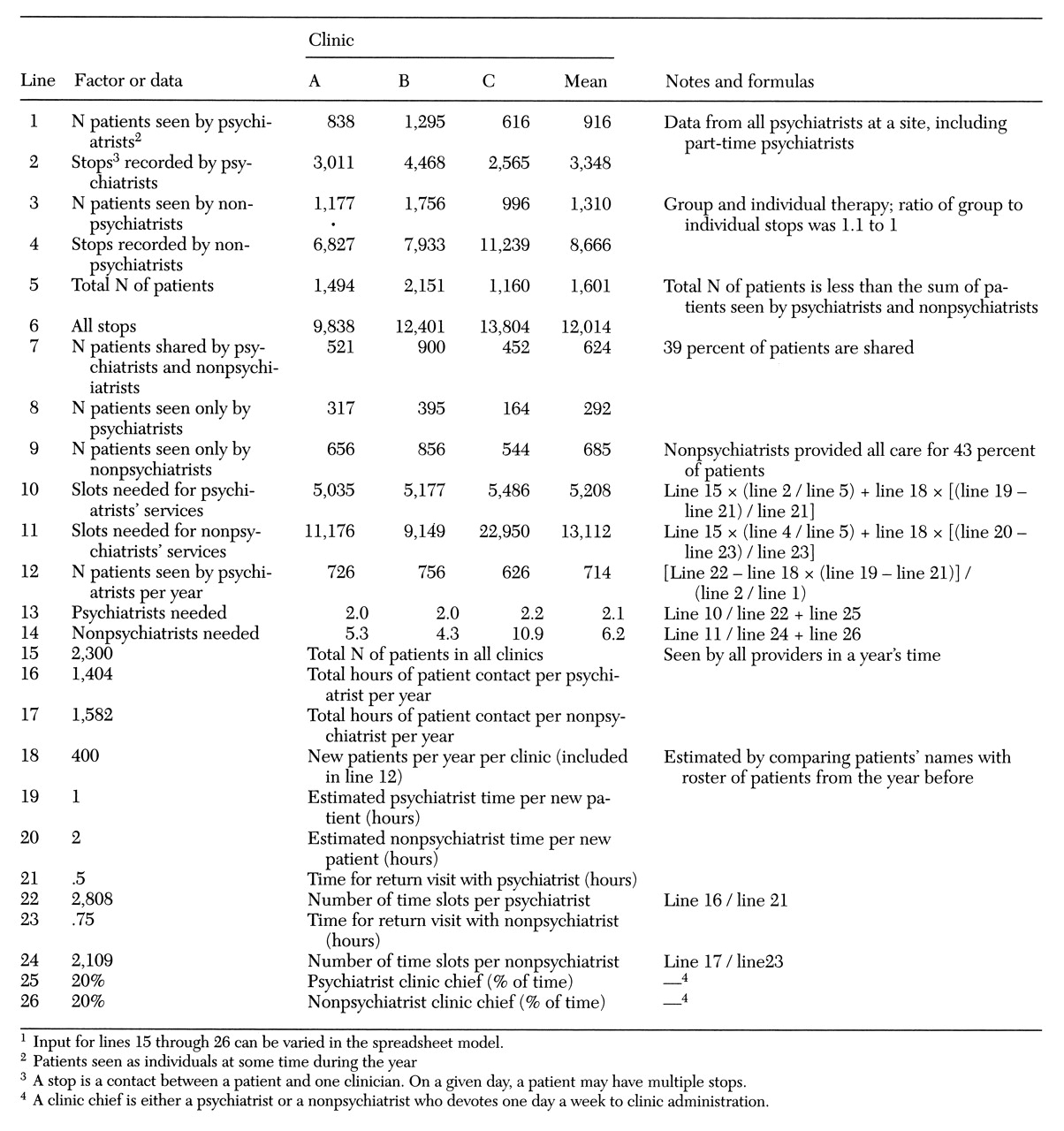

The following assumptions, which are used in the model shown in

Table 1, approximate those of Goldman and associates (

4). Assuming eight hours in each working day and 251 workdays in a year (less 20 days for vacation and 15 days' absence for conferences, training, or sick leave), each clinic psychiatrist has 1,728 available working hours a year. Each psychiatrist uses 1.5 hours a day for meetings and emergency and telephone consultation, leaving 1,404 hours a year for face-to-face patient care (line 16 of

Table 1). Nonpsychiatrist clinicians are allowed different amounts of time for leave and consultation; thus they have 1,582 hours a year available for face-to-face patient care (line 17). It was also assumed that 400 new patients will be seen in a year (line 18). This figure was based on one clinic's experience. Furthermore, each new patient requires one hour of psychiatrist time and two hours of nonpsychiatrist time (lines 19 and 20); returning patients need 30 and 45 minutes, respectively (lines 21 and 23). The last assumption was that one clinician (psychiatrist or nonpsychiatrist) at each site devotes one day a week to clinic administration.

Results

Table 1 shows the figures and formulas needed to calculate how many patients a psychiatrist can manage. Results are shown for each of the three clinics and as a mean for the three clinics. Using the stated assumptions, the number of patients ranges from 626 to 756, with a mean caseload size of 714 patients per year (line 12). A clinic staff comprising two psychiatrists and five or six nonpsychiatrists who are managed by a physician should be able to evaluate 400 new patients a year and provide ongoing care for a caseload of 2,300 individual patients seen at some time during the year.

Discussion

Some of the assumptions used in these calculations require explanation. Although 15 days a year for training or sick leave may seem high, it approximates VA's actual time allowance. A three-hour evaluation for a new patient by a psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist staff includes time for interviewing informants, reviewing charts, requesting additional material, recording impressions, and arranging a disposition.

Allowing 45 minutes for a patient who is returning to a nonpsychiatrist clinician who has 1,582 available hours yields 2,109 slots a year (line 24), a workload an efficient mental health professional should be able to manage. For example, during the year of the study, one nurse recorded 2,600 stops (patient contacts); a social worker who recorded 1,800 stops said she could do more; and another nurse felt that 1,800 stops occupied her fully. More group therapy sessions could increase the efficiency of all staff members; the ratio of group-to-individual stops in these clinics was approximately 1.1 to 1.

The results of the computations were reasonably consistent across the three sites, although clinic C's time per patient clearly exceeded that of the other two clinics (lines 10 and 11). The model predicts that a psychiatrist practicing according to the VA team model can manage two to three times as many patients as one working in the clinic described by Goldman and colleagues (

4).

Some of this apparent difference may be due to differences in the patient populations in the two types of setting. The patients in Goldman's study may have been more acutely ill and may have required more psychiatrist time than do typical VA mental health patients. However, part of the difference must be due to the nonpsychiatrist VA providers' having the first contact with most drop-in patients, which allows the psychiatrists to adhere to a tight schedule for seeing patients. In addition, the paramedical staff provide psychotherapy for patients who require medication. With back-up by a psychiatrist, the paramedical staff are the exclusive care providers for more than 40 percent of all patients (line 9).

VA patients receive general medical care through traditional primary care channels. Thus the model addresses neither the physical health care needs of patients seen in a psychiatric primary care clinic nor the special needs of those with a substance use disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, who were seen elsewhere in mental health specialty clinics. By varying input or levels of service required in the full spreadsheet model, the model can be modified to fit the requirements of either a psychiatric primary care clinic or a mental health specialty clinic. Clinics can use the model to determine their own staffing requirements, even when some providers devote part of their time to academic activities, inpatient care, or administration.

No provider in the VA clinics in the study reported feeling overworked. The numbers (stops per employee) used in the model were derived from actual data collected during the course of a year. Thus the model does not set an ideal standard but reports on an actual workload accomplished by VA employees.

Of course, this model leaves untested the critical assumption that the practice patterns of these clinicians are both appropriate and efficient. With changing incentives brought about by managed care, assumptions about appropriate treatment have dramatically changed. One should be wary of any model derived without recourse to patient outcome data. Until administrators find methods that use case mix and diagnosis-specific outcomes to determine staffing patterns, this method can help managers adjust staffing levels to fit current patient needs.

Conclusions

Combining actual data with theoretical assumptions helps determine staffing requirements for all providers, not just psychiatrists. A staffing model that uses paramedical staff permits more efficient use of psychiatrist time than models that consider only the psychiatrists' effort. The assumptions stated in the spreadsheet model can be adapted to various levels of provider availability and workload demands. However, because the model rests on data collected from only one clinic system, its generalizability to other systems requires testing.