In the context of deinstitutionalization, issues of sexuality, partnership, and parenting among women with severe mental illness have attracted increasing attention. Women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders are more likely to have a history of sexual victimization or prostitution (

1,

2,

3,

4), have more unplanned pregnancies and higher fertility rates (

4,

5), and have less stable partnerships (

1,

4) than women without psychiatric illnesses. Furthermore, women with serious mental illness lose custody of their children more frequently than do those without psychiatric illness (

4,

6).

A recent review of issues of sexuality, pregnancy, and parenting among women with schizophrenia concluded that one priority was to improve assessment of parenting capacity and provision of parenting skills training (

7). To do so, researchers and program planners need more information about the circumstances and perceived needs of women psychiatric patients who are mothers.

The pilot study described here was a cross-sectional prevalence survey developed to address two research questions. First, what is the demography of mothering in a population of seriously mentally ill urban women? In particular, what proportion of women have children, how many children do they have, and what proportion retain instrumental or affection ties to their children? Second, what are the perceived needs of these mothers with respect to their children?

Methods

Given the objectives of this study, the population of interest was described functionally, rather than diagnostically, as women with severe psychiatric illness. The study group consisted of women hospitalized at an inner-city, state-funded facility serving persons with severe mental illness. It should be recognized that the participants in this study are not generally representative of the broader group of women with psychiatric illness but are likely to resemble similar populations cared for in other urban American psychiatric hospitals.

In 1996, as part of a survey of all clients in the facility, women able to read and write English were approached and invited to complete an additional questionnaire. The purpose of the pilot study, its voluntary nature, and the anonymity of the questionnaire were explained, and informed consent was obtained.

The brief questionnaire was developed in consultation with a senior family therapist at the facility (MA), who had worked with many women clients about issues of mothering. The questionnaire incorporated specific items proposed during preliminary focus group discussions with women on one ward who were mothers. The questionnaire required less than one minute to complete if a woman had no children, and a maximum of 15 minutes if a woman had several children and was a slow reader.

Statistical analyses were confined to the calculation of simple proportions and percentages. No tests of statistical significance were performed.

Results

Questionnaires were distributed during the summer of 1996 to 65 women. Fifty-two women completed it, yielding a response rate of 80 percent. No information about the characteristics of nonrespondents was available.

Of the 52 women, 32 women, or 61.5 percent, reported having had at least one child. The remainder of this report is based on the data provided by these 32 women. At the time of the survey they had a mean age of 44.3 years, with a range from 29 to 66 years.

Respondents reported having a total of 61 children, ranging in age from three to 40 years, with a mean age of 20 years. Although almost half of the children were already adults, the remainder were almost evenly divided between those under age 13 and those who were already teenagers. The vast majority of the children (96.7 percent) were not yet adults when their mothers were hospitalized for the first time.

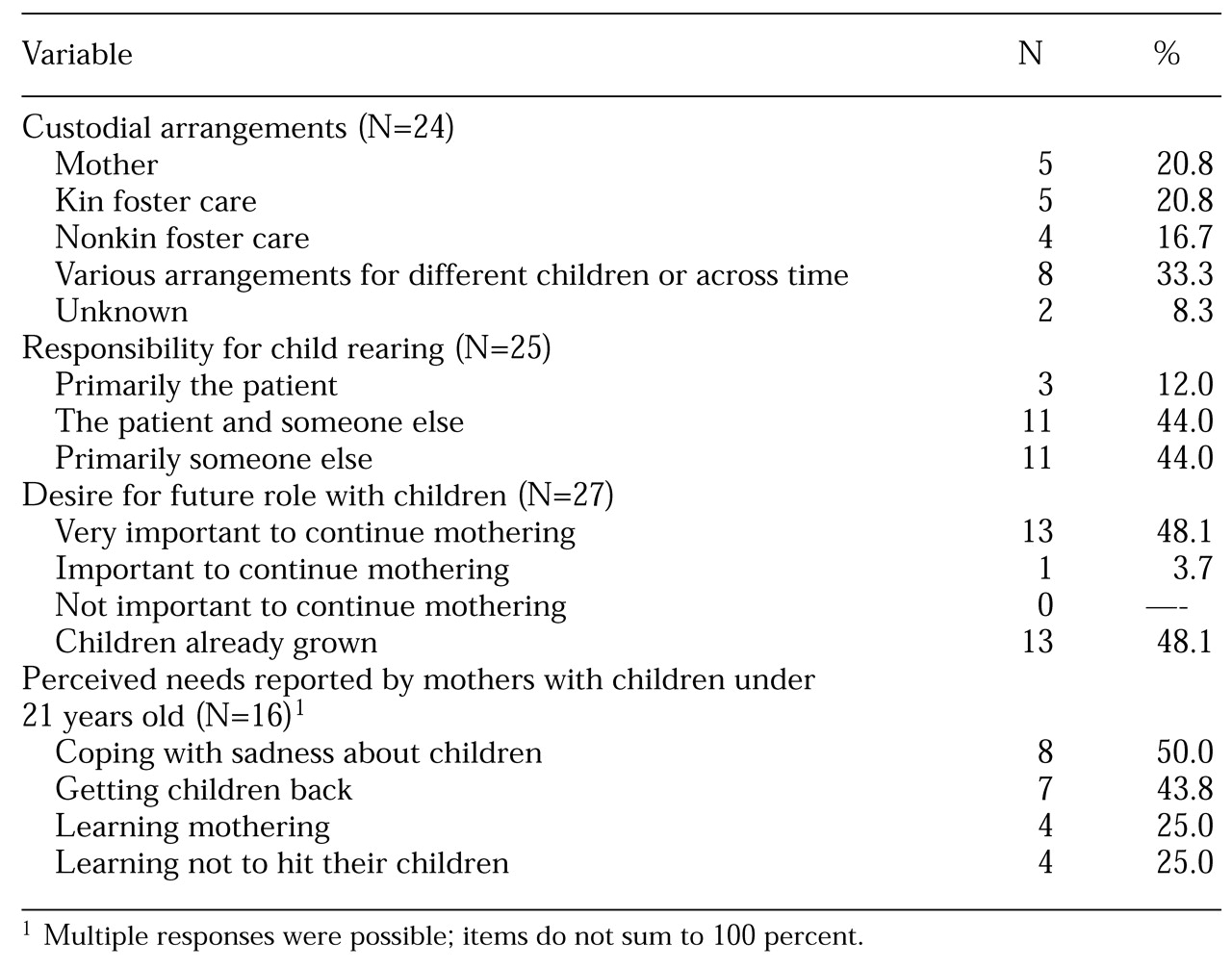

As shown in

Table 1, hospitalized mothers were generally not able to be involved in taking care of their children. (Because not all questions were answered by all the women, percentages were calculated based on the total number of respondents for whom data were available.) Only seven respondents, or 22 percent, had seen their children within the past week. Twelve respondents, or 38 percent, had not seen their children in more than two years or could not even recall when they last had seen their children.

Only five mothers, or 21 percent of the 24 mothers for whom data on child custody were available, retained full custody of their children. Eight mothers, or 33 percent, described custodial arrangements that differed for various children or differed across time for the same child. Not unexpectedly, only three mothers, or 12 percent of the 25 mothers for whom data were available, described themselves as the primary person raising their children. The majority of the mothers were equally divided between those who helped someone else raise their child and those whose children were being raised by others.

However, it is noteworthy that none of the respondents felt that continuing to mother their children was unimportant. Virtually all of the mothers whose children were not grown indicated that it was very important to continue to help raise their children. In addition to a wide range of instrumental and relational needs, 15 of the 32 participants described themselves as needing help in dealing with their own sadness about their children. Women with grown children did not differ substantially from those with younger children in this respect. Although substantial numbers also felt they needed help in getting their children returned to them, in learning how to be a mother, or in learning how to avoid hitting their children, these needs were less frequently identified (see

Table 1).

Discussion and conclusions

A concern might be raised about the validity of data obtained from a self-completed questionnaire administered to women whose thinking is likely to be disordered. Although we could not validate their responses, in the aggregate the data can be compared with data obtained in other studies, offering at least limited support for their validity. For example, 38 percent of the mothers in this study reported that their children were in some form of foster care, compared with 48.5 percent of mothers in a study by Miller and Finnerty (

4) of women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. In that study, 36.4 percent of mothers reported raising their children with someone else, a figure similar to the 44 percent reporting such arrangements in our study. The results of our study are also consistent with qualitative and clinician-reported data provided by Nicholson and colleagues (

8,

9).

Despite the severity of their illnesses, the majority of the 52 women who completed questionnaires in this study were mothers. Even if all 13 nonrespondents had no children, almost 50 percent of the women in the sample were mothers. Further work is required to obtain valid estimates of the prevalence of motherhood among psychiatric patients, but these pilot data suggest that mental health practitioners treating even the most seriously impaired women often need to take account of issues related to motherhood.

These preliminary data also provide potential clues about the clinical and rehabilitative issues that need to be addressed among patients who are mothers. It is apparent that the treating clinician or team may confront a complex and demanding task because custodial arrangements are often diverse and contact with the children is infrequent. This isolation of patients who are mothers from the realities of their prehospitalization lives may tempt clinicians to ignore the seemingly more remote problems while attending to immediate symptoms and rehabilitative concerns. However, in this pilot study, respondents reported that that they want help in coping with what often amounts to the loss of their children and in successfully maintaining some relationship with them.