In a recent column for this series, Glazer (

1) discussed the need for psychiatrists and other mental health workers to reestablish control of the patient-provider relationship in this era of managed care. He suggested that methodologies to identify and implement best practices might go a long way toward achieving that goal.

He also argued that the collective cottage-industry mentality of psychiatry and other mental health disciplines is an obstacle to regaining professional autonomy. The effects of this mentality are critically important in the changing world of medicine. Medicine is indeed in the midst of a transition from an old-fashioned cottage industry into a truly industrialized business. This change is not unexpected, for such transitions occur in the natural history of all business sectors.

Many examples of this process can be found in history. The experience of one well-known cottage industry is instructive. Before Henry Ford's development of the automobile assembly line, local artisans working at the behest of individual customers built automobiles and other carriages. But Ford's model for the industrialization of automobile manufacture led to a significant transition for that business sector and its practitioners. Surely the carriage makers fought this transition, and surely they grieved the change, for it brought along a loss of autonomy and the personal relationships that these artisans had developed with their customers. Unable to compete financially, the artisans gave way to unionized workers on assembly lines. The old-fashioned carriage makers (including my grandfather) had to find another way to make a living.

Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals currently walk a similar plank toward the same fate. As we do, we bemoan the sight of "managers with clipboards" walking in the opposite direction—those faceless bureaucrats perceived as more concerned with money than with quality who nonetheless seem to be taking control of our industry (

2). If we are to avoid that fate, we must learn to manage ourselves with those same clipboards. If we do not, then the business and congressional leaders who foot the bill for health care will continue to turn to others—not to psychiatrists and other mental health professionals—for advice on how to manage mental health care. If we do not learn how to manage our work financially as well as clinically, then we will be turned into technicians and relegated to the same fate as previous generations of cottage industry practitioners.

This column presents a method used by the physician leadership in our community mental health center to think like managers with clipboards. Specifically, it describes the management process for financial and clinical performance indicators for our center's psychiatric staff. It is critical that we focus on both financial and clinical performance, because payers in our burgeoning industry will not hear our message about clinical best practices unless we, as practitioners, demonstrate our ability to keep our financial house in order.

The setting

The performance indicators and management methods were developed for the psychiatrists serving adult consumers in our large community mental health center in Houston. Most of the center's adult mental health services are provided through six outpatient community mental health clinics located throughout the county.

Each clinic has from three to six full-time psychiatrists, each of whom provides clinical leadership to a multidisciplinary treatment team. One of the psychiatrists at each site also serves as clinic medical director. The members of each team together care for about 300 patients. The diagnoses of patients and the severity of their illness are fairly consistent across treatment teams. Almost all patients have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder. The team-based physicians also serve as the primary source of referrals to other rehabilitation services provided by their team or by other programs in the center.

Performance indicators and the management process

The performance indicators have been described previously (

3). Briefly, the indicators measure a series of parameters related to productivity, outcomes, and appropriateness of care. At the end of each month, a new set of performance data is collected for each physician. Except for scores from reviews of the quality of medical records, all of the data required for the indicators are available from reports generated by the center's information systems department.

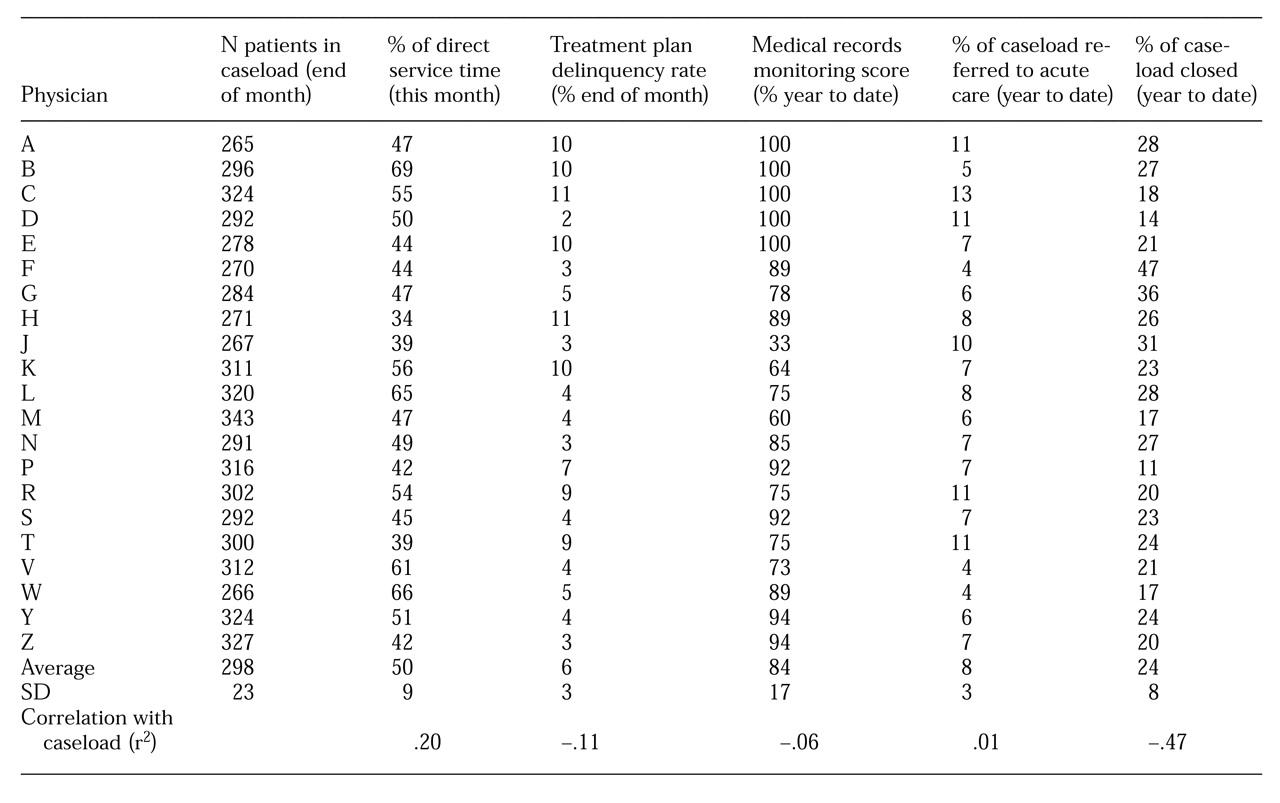

Table 1 shows examples of the physician performance indicators for a sample month in a spreadsheet display. The indicators are listed at the top of the columns. Physicians are listed by name in the left-hand column (although the names have been removed for this report). For each performance indicator, a mean and standard deviation are calculated by the computer-based spreadsheet for all physicians throughout the center.

All physicians receive the entire spreadsheet each month. Because many systemic problems can affect individuals' performance, physicians are asked to comment on their personal indicators that fall more than one standard deviation outside the mean for the group as a whole. High-performers are asked for feedback on local procedures that have facilitated their performance. Responses may lead to systemic interventions at the team level, within the clinic, or even throughout the center. Descriptions of procedures that have enhanced performance are communicated to the entire physician staff through an e-mail network.

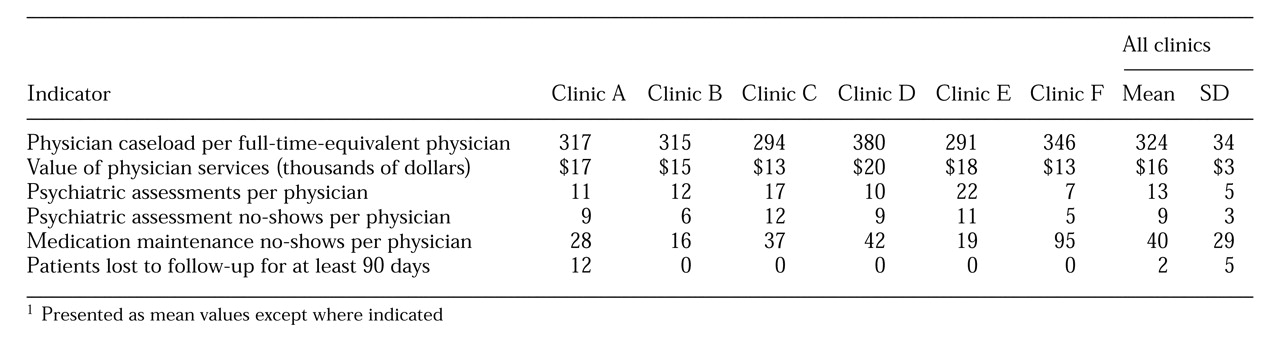

Similar indicators can be developed at the clinic level. Examples of such indicators and sample data are shown in

Table 2. In this spreadsheet display, the various clinics are named across the top of the columns, and the sample performance indicators are listed in the left-hand column. Again, means and standard deviations for the entire center are calculated using the computer-based spreadsheet. Like the data on the individual performance indicators, the clinic-level data are shared with the medical directors of all clinics. The directors of clinics with outlying data are asked to comment on possible reasons for the high or low performance, and plans for improvements are generated, if indicated.

The impact of simply monitoring the individual physician productivity indicators and sharing the results with the center's physicians appears to have been significant. An increase in productivity, measured as the mean amount of time physicians spend in direct service, occurred over 12 months of monitoring, with a trend toward improvement in productivity over the year (r2=.86, p<.001). The improvement represents an average monthly increase of about $4,000 in value of services per physician. This improvement was obtained without browbeating, without formal or informal disciplinary procedures, and without the setting of requisite indicator targets.

Individual and centerwide trends in clinical indicators can be managed in a similar manner. For example, a study of the centerwide show rate for new patients referred for hospital aftercare, calculated from clinic totals each month, showed a trend toward improvement (r2=.32, p=.05). This change suggests, again, that the identification of continuity of care as a quality indicator was sufficient to evoke an effort for improvement within the clinics.

Other management issues are worthy of exploration. For example,

Table 1 shows the correlation of clinical indicators to caseload size. The negative correlation between caseload size and rate of case closure (r=-.47) suggests that physicians with high caseloads tend to have patients who stay in treatment. Does this relationship represent a tendency to keep cases open longer than needed, effectively "padding" caseloads as a means of avoiding assignments of new patients? Or, does it suggest that some physicians and treatment teams do a better job of engaging and retaining patients in treatment? These questions may be addressed through data collection and trending analyses that augment the basic performance indicators.

Conclusions

Managed care has changed the nature of the relationship between psychiatrists and other mental health workers and their patients. Payers in this new era insist on the types of performance indicators described in this column to ensure the quality and efficiency of the services they fund. They also insist that clinical leadership address the kinds of quality assurance questions raised by collected data. We, as mental health professionals, must demonstrate a parallel commitment to both quality and fiscal responsibility. Once this commitment has been demonstrated, adversarial relationships will diminish. In their place, new alliances can form among providers and payers that will not only ensure high-quality care for our patients in the present, but also secure our professional autonomy in the future.