The era of community-based treatment for serious mental illness has witnessed greater numbers of men and women with schizophrenia experiencing parenthood (

1,

2). Considerable evidence exists that the fertility rate of people with schizophrenia, which was far below that of the general population before the late 1950s (

3), increased markedly following deinstitutionalization of mental health services (

1,

2,

4). It has been estimated that the fertility rate of women with schizophrenia now approaches that of the general population (

2), with whom former patients share the universal aspirations to establish intimate ties and have children.

An increasing number of descriptive studies based on small, selected samples have explored sexuality, pregnancy experiences, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10). Such studies have revealed that pregnancies are often unplanned (

5,

6,

7) and that only a minority of patient-parents are able to provide consistent nurturing of their children due to the chronic and relapsing nature of schizophrenia and its accompanying social disability (

8,

9,

10). However, very little research has examined the association between parenting and premorbid characteristics of patients or the course and outcome of their illness. This paper is one attempt to address that gap.

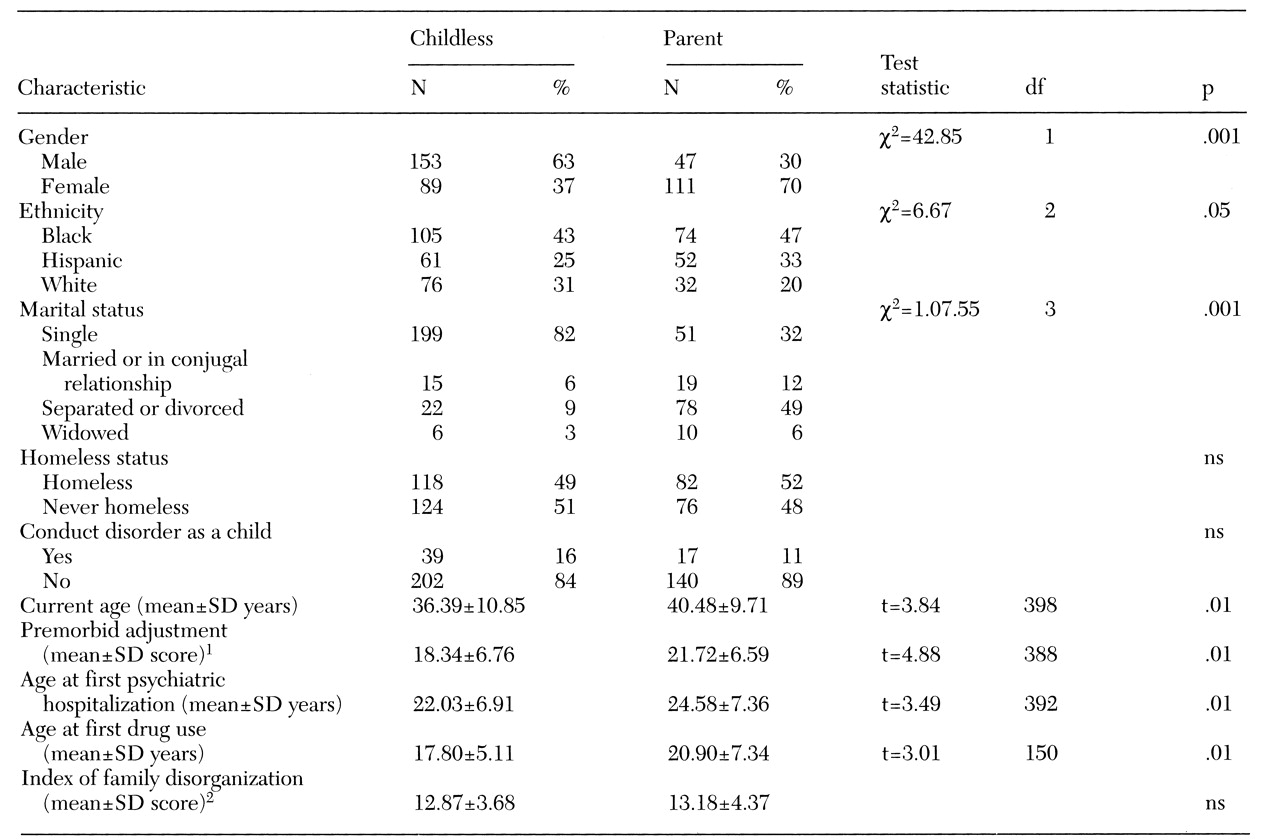

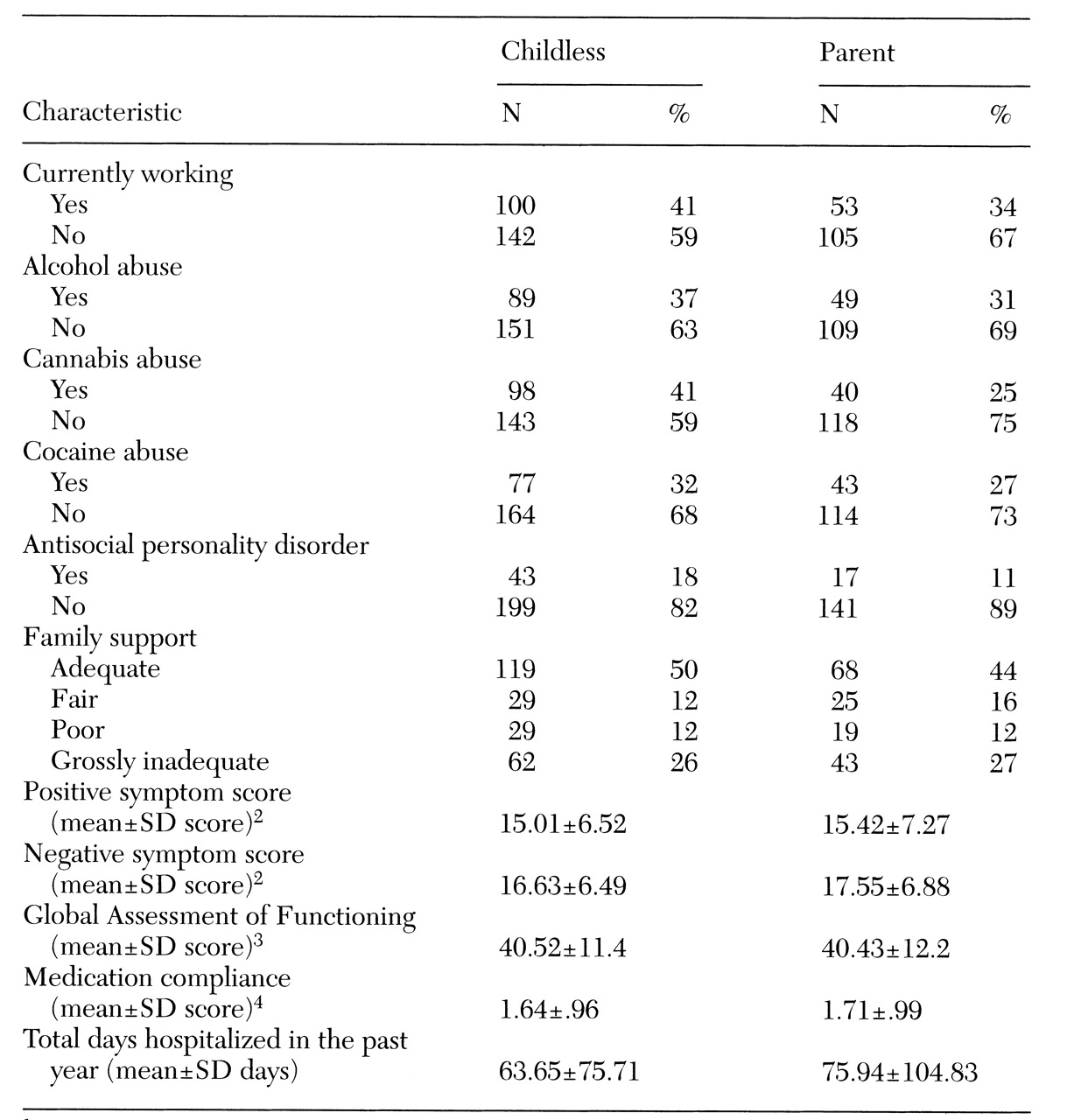

In this study, we explored the clinical, demographic, and background characteristics and social functioning of patients with schizophrenia who became parents and those who remained childless. We examined whether parents differed from childless subjects in premorbid characteristics or clinical and social adjustment. We discuss the findings in relation to the expanding literature on parenting and schizophrenia.

Methods

Study subjects were 400 men and women with chronic schizophrenia originally selected on the basis of their housing history in connection with a cross-sectional study of risk factors for homelessness. All subjects had experienced at least one psychiatric hospitalization and were between the ages of 18 and 64 years. Half the patients in the sample were currently residing at a shelter for the homeless, and the other half were psychiatric outpatients or discharge-ready inpatients on public psychiatric units for patients with severe mental illness. To be eligible for inclusion in the study, subjects were required to meet

DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, which was determined through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (

11).

Potential study subjects were referred by clinical staff based on the subject's chart diagnosis, treatment history, and ability to give voluntary informed consent. A total of 497 subjects, recruited consecutively between 1988 and 1992 from shelters for the homeless and mental health inpatient and outpatient programs in an urban area, were asked to participate in the study. Thirty subjects (6 percent) refused, and 34 (7 percent) dropped out before completing the interview. Thirty-three subjects (7 percent) with completed interviews were eliminated because of inconsistent or poor-quality data that could not be improved with a re-interview. The remaining 80 percent of subjects constituted the sample of 400.

Subjects were interviewed by mental health clinicians experienced in working with severely mentally ill patients. They were specially trained to administer the research instruments used in this investigation. Clinical and anamnestic data were verified with information contained in the clinical case record. When both the patient and a relative agreed, an hour-long interview with a family member was also carried out. All study subjects provided written informed consent before being interviewed.

Research instruments used to assess key study variables, which are described elsewhere (

12), are summarized briefly here. Premorbid social functioning was rated with the Los Angeles Social Attainment Scale, a seven-item instrument that is focused on peer relationships and social participation in late adolescence (

13). The alpha reliability coefficient for this scale is .80.

The positive dimensions of schizophrenia (active psychotic symptoms such as delusions, hallucinatory behavior, and conceptual disorganization) and the negative dimensions (deficit symptoms such as blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and difficulty with abstract thinking) were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, a 30-item rating scale evaluating symptoms present during the seven days before the interview (

14). The alpha reliability coefficient was .79 for the positive scale, .84 for the negative scale, and .83 for the general psychopathology scale.

Current and lifetime alcohol and drug abuse or dependence were evaluated with the SCID, which yields information on the extent to which heavy use of alcohol or seven classes of drugs meets criteria for a diagnosis based on standards commonly applied in psychiatry (

11).

Antisocial personality disorder was evaluated with the SCID-II, which deals with personality disorders (

11). This instrument probes for the presence of conduct problems occurring before the age of 15, such as running away from home, being a truant from school, initiating physical fights, or belonging to a gang, as well as patterns of irresponsible, destructive, or illegal activity carried over into adulthood. For a subject to meet criteria for a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, a conduct disorder must have been present in early adolescence. The SCID also rates axis V, social functioning, on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, with ratings from 0, poor, to 100, best.

Family disorganization in childhood was evaluated with 4-point rating scales contained in the Community Care Schedule (

15). These ratings are based on carefully defined anchor points for the assessment of nurturing constancy, residential stability, adequacy of income, dependence on public assistance, family violence, parental criminality, parental mental illness, and parental substance abuse—the components of an index of family disorganization. Information for this instrument was elicited from both the subject and a family member whenever possible to obtain the most complete picture of family life during the subject's childhood. The alpha reliability coefficient for the seven-item index of family disorganization is .69.

Current family support was rated on a scale of adequacy, based on the degree of support and assistance available from family members in the areas of money, shelter, food, clothing, advice, and companionship (

15). Information for this rating was obtained from the subject and corroborated by a relative when possible.

Prior service use was explored with items contained in the Community Care Schedule that were designed to elicit detailed information on medication compliance patterns, long-term follow-up care, and rehospitalization episodes. Medication compliance was rated on a 4-point scale based on the subject's self-report. Long-term follow-up care was defined in terms of the number of months in outpatient treatment with the same therapist. The number of days hospitalized in the past 12 months was recorded based on the subject's self-report.

We described the differences between parent and childless groups in demographic, background, and clinical characteristics and social functioning. These variables were summarized as percentages for categorical variables and means for quantitative variables. Pearson chi square and t test statistics were used to study statistical differences between the parent and childless groups.

Discussion and conclusions

We examined parenting and adjustment using data from 400 men and women with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were originally selected for a study of risk factors for homelessness. Half the subjects were homeless when they were interviewed, and although the other half had never been literally homeless, they shared many of the social characteristics (minority ethnic status) and economic characteristics (living on the edge of poverty) of homeless subjects. We found important differences in the characteristics of subjects with schizophrenia who became parents and those who remained childless. Compared with childless subjects, parents were more likely to have had better premorbid social adjustment, to have ever been married or involved in a conjugal relationship, and to have experienced the onset of illness at a later age.

The majority of parents had their first child before the onset of their illness, and only a quarter of the children (27 percent) were born after the parent's first psychiatric hospitalization. Therefore, deinstitutionalization did not appear to be an important factor in why these patients became parents. More women than men became parents. The fact that age of onset of schizophrenia is often later in women than men may at least partly account for this finding (

16,

17). Parents were more likely than childless subjects to be members of ethnic minority groups.

It is possible that an important component of the gender difference in parenthood is the biological inevitability that women bear the reproductive consequences of sexual activity. Men may not always have knowledge that a pregnancy has occurred as a result of sexual activity, particularly if it occurs outside of a meaningful relationship. Recent research on the sexual behaviors of people with severe mental illness, carried out in connection with research on HIV-AIDS risk assessment, has revealed that the rates of sexual activity for men and women are comparable (

18). Unprotected sexual activity is widespread among persons with severe mental illness. The fact that women are more often faced with the outcome of unprotected sexual activity underscores their need for access to family planning and reproductive services in settings that treat women with schizophrenia (

19).

No differences were found in the current clinical and social adjustment of parents and childless subjects. However, parents' adjustment was no better than that of childless subjects, even though parents had better premorbid adjustment and were more likely to have established at least a temporary relationship with a significant other. Thus parenthood did not have a favorable impact on the clinical course of schizophrenia, and it may be that the stressors of the parenting role offset whatever advantages were conferred on parents by better premorbid functioning.

However, our findings are preliminary and require replication with socially and economically diverse samples of people with schizophrenia. Because our study was cross-sectional, we might have missed fluctuations or changes in clinical and social functioning over time that might be related to life events occurring in relation to parenting, such as the impact of pregnancy (

20) and the postpartum period or loss of custody of children. At the very least, adjustment of medications, as well as awareness of their safety profiles in pregnant and nursing women, can become an important clinical issue. Our measures of adjustment did not address the fact that parenting is a life role that can be enriching and growth enhancing.

An important caveat is that even if being a parent or remaining childless does not alter the course of severe mental illness, parenthood can impose increased stresses and challenges for parents with schizophrenia and for their children, requiring specialized mental health treatment and support services (

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25). A previously reported study of the offspring of these subjects found that most patient-parents lived with their offspring at some time but relied heavily on relatives and other adults to provide their offspring with consistent nurturing (

26). As many as a third had children placed in foster care.

In conclusion, patients who experience a later onset of schizophrenia or have better premorbid social skills are more likely to undertake marriage and parenthood. Whether offspring are born before or after the parent's onset of illness, patient-parents are likely to need special support for the parenting role once the illness begins and takes its typical course (

27).