The death rate from AIDS has been declining since 1996, which is attributed to advances in biomedical treatments with combination antiretroviral medications (

1). This good news is tempered by surveillance data showing disproportionate rates of HIV infection among ethnic minority Americans, especially women, youth, and children. Prevention of HIV infection is still the best strategy for addressing the future course of the AIDS epidemic. Survey data from the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Research Network (PRN) (

2) suggest that psychiatrists can play a role in the prevention effort.

In 1997 all PRN members, a total of 531 psychiatrists, were sent a mail survey on psychiatric patients and treatments that included questions about their patient caseload in their last typical work month across all work settings. Specifically, they were asked about the total number of patients treated, the number who were HIV seropositive, and the number who had any risk factor for HIV infection based on their knowledge of the patient's behavior, including unprotected sex, injection drug use, and occupational exposure. A total of 417 psychiatrists, or 79 percent, responded to the survey, and more than 96 percent of them provided data on HIV prevalence and risk among their patients. The results presented are based on unweighted data.

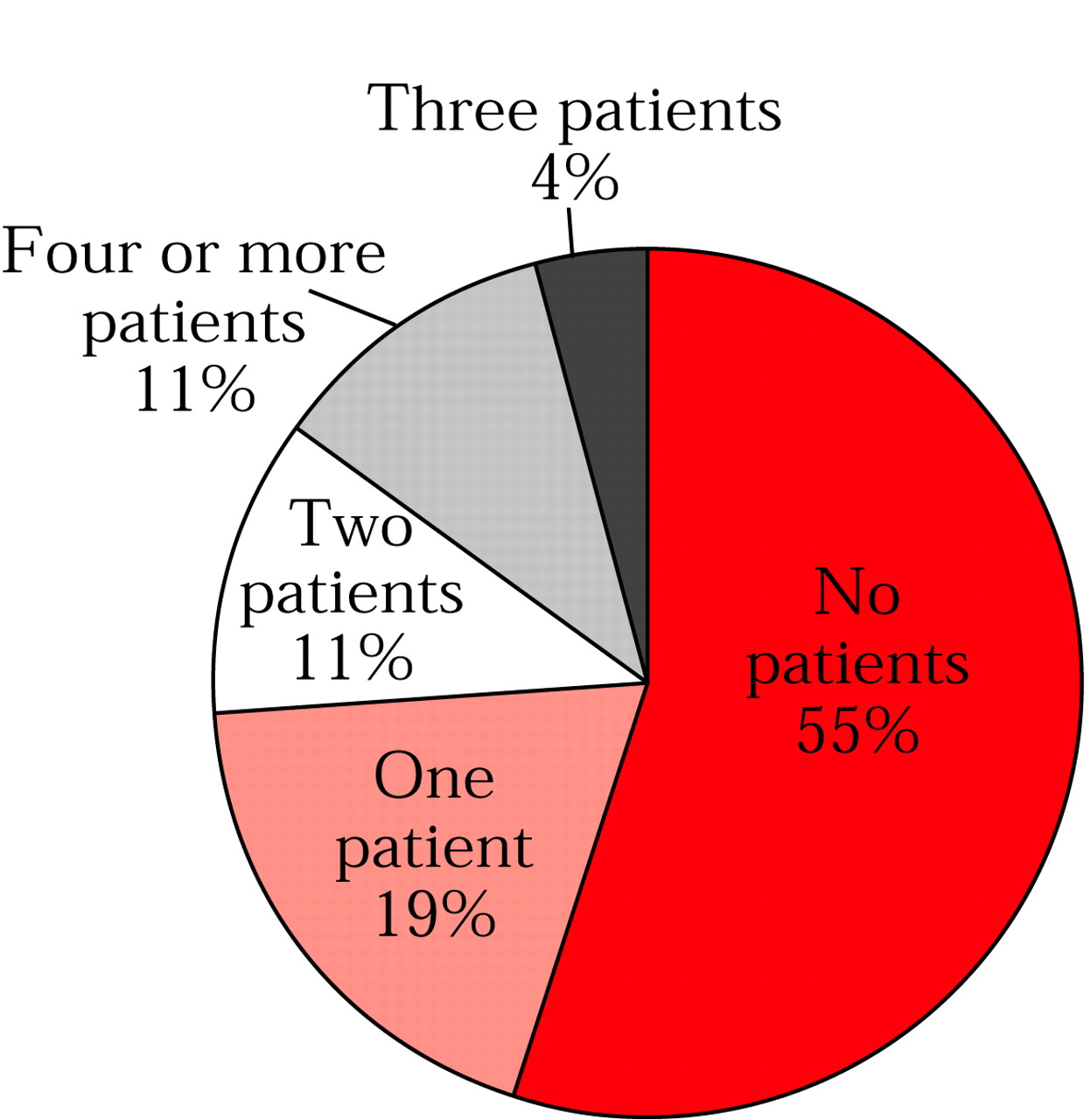

The psychiatrists saw an average of 131 patients a month, ranging from fewer than 50 patients (seen by 19 percent of the psychiatrists) to 300 or more (seen by 6 percent); most respondents (31 percent) saw between 100 and 199 patients a month. Although less than half reported seeing at least one HIV-positive patient in a typical month (

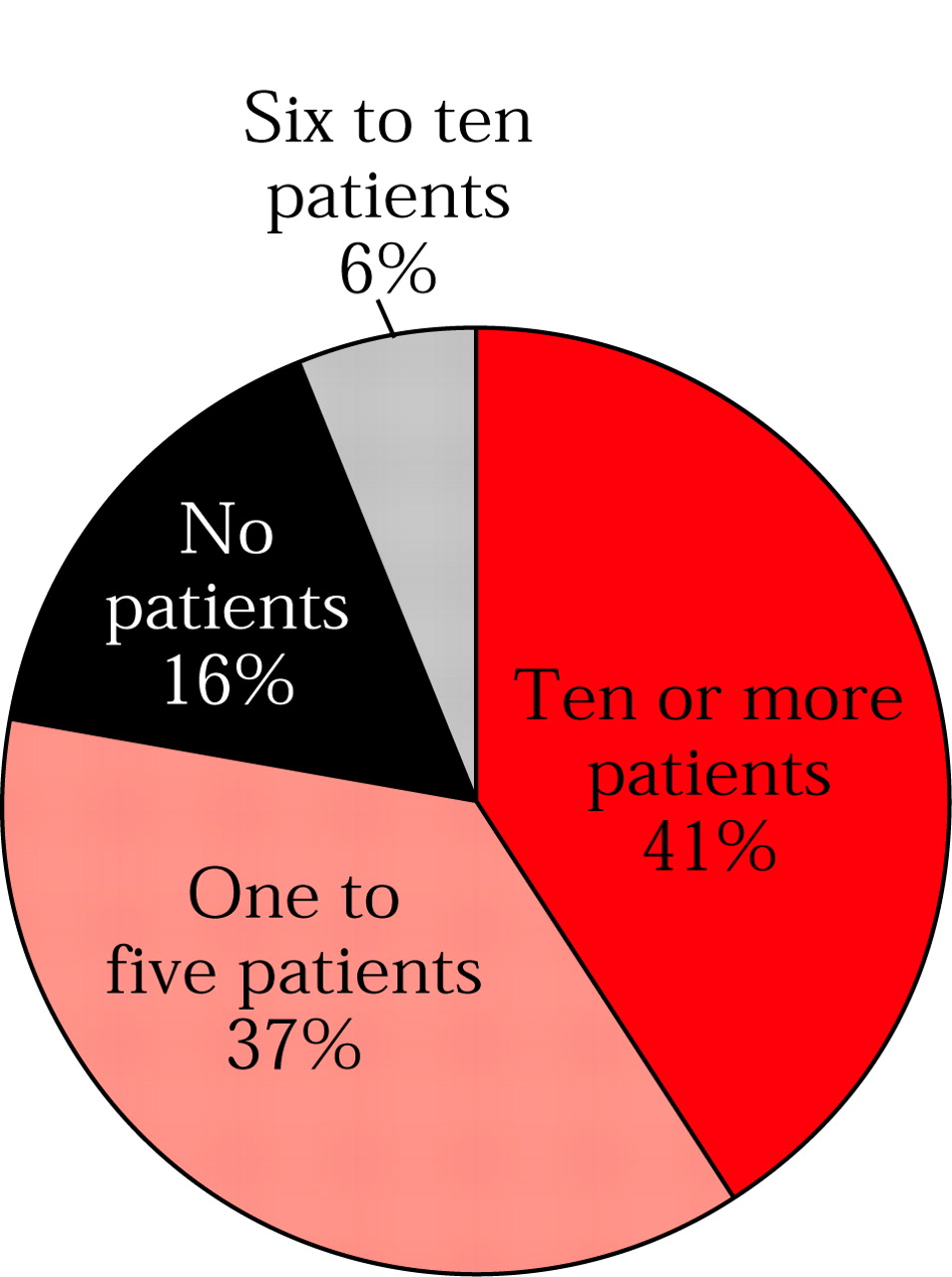

Figure 1), 84 percent reported seeing at least one patient who was at risk for HIV infection (

Figure 2). Furthermore, while less than 1 percent (one patient) of the mean number of patients seen each month were HIV positive, 9.2 percent (12 patients) were considered to be at risk for HIV infection.

The data suggest that psychiatrists typically have clinical encounters with a significant number of patients for whom prevention of HIV infection can be addressed through changes in risk behavior. Therefore, psychiatrists are in a position to actively educate their patients about prevention of HIV infection. APA is currently in the process of developing practice guidelines on HIV/AIDS to help psychiatrists with educational efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Center for Mental Health Services.