Many persons with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder could benefit from participation in self-help groups focusing on substance abuse. As many as 50 percent of persons with serious and persistent mental illness have co-occurring alcohol or drug abuse (

1). Compared with persons with serious mental illness who do not have substance abuse problems, those with a dual diagnosis are less compliant with medication, exhibit poor self-care, are more disruptive, and are more frequently rehospitalized (

2).

Substance abuse self-help groups, including Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), are underused by persons with a dual diagnosis even though such groups are free and available in most communities (

3). Considering that sobriety is critical for them, it is important to better understand how they can more successfully use AA. A majority of dually diagnosed persons do not attend neighborhood AA meetings, even if encouraged by a provider (

4). Further, many clinicians are reluctant to refer persons with psychiatric disorders to 12-step groups because they worry that AA members are skeptical of mood-regulating medication and realize that AA focuses exclusively on addiction (

5,

6). To better understand these issues, we assessed attitudes and experiences of AA "contact persons" about the participation of mentally ill persons in their groups.

Methods

Respondents were 125 persons answering the telephone number of AA groups in Midwestern states during the later part of 1996. Groups were located through AA central offices, telephone directories, and the database of the Self-Help Network of Kansas, a statewide self-help clearinghouse. Most AA groups listed phone numbers of experienced members, whom we termed "contact persons." They were targeted for the survey because they would be the same persons contacted by a person with mental illness or by a mental health worker who is interested in AA.

Of the 169 AA contact persons asked to participate in the survey, 125 completed the survey, for a response rate of 74 percent. Before being asked questions about mental illness, contact persons were read a description of symptomatic behavior related to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression.

Respondents had been members of their AA group for a mean of 6.7 years, and they had been a contact person for a mean of 4.9 years. About 25 percent were female. When asked about their role, they described themselves as active members (47 percent), role models (9 percent), board members (9 percent), meeting facilitators (6 percent), or "trusted servants" (5 percent). No other demographic information was asked due to respect for AA's traditions of anonymity.

The instrument was a telephone survey designed to assess attitudes and beliefs of AA contact persons about persons with mental illness. Respondents rated their level of agreement with several statements about whether mentally ill persons would fit in their AA group, would be a valuable member, and would be just as good a member as a person without psychiatric problems. They were also asked if persons with a psychiatric illness should continue taking prescription medication. Respondents rated each statement on a 6-point scale ranging from 6, strongly agree, to 1, strongly disagree.

Participants were also asked about their level of knowledge of mental illness, their past personal experience with mentally ill persons, and their attitude toward that experience using the same 6-point scale. They were also asked whether past members of their AA group had a mental illness and if it was better for a person with a mental illness to become a member of their group or of one made up of persons with dual diagnoses.

Results

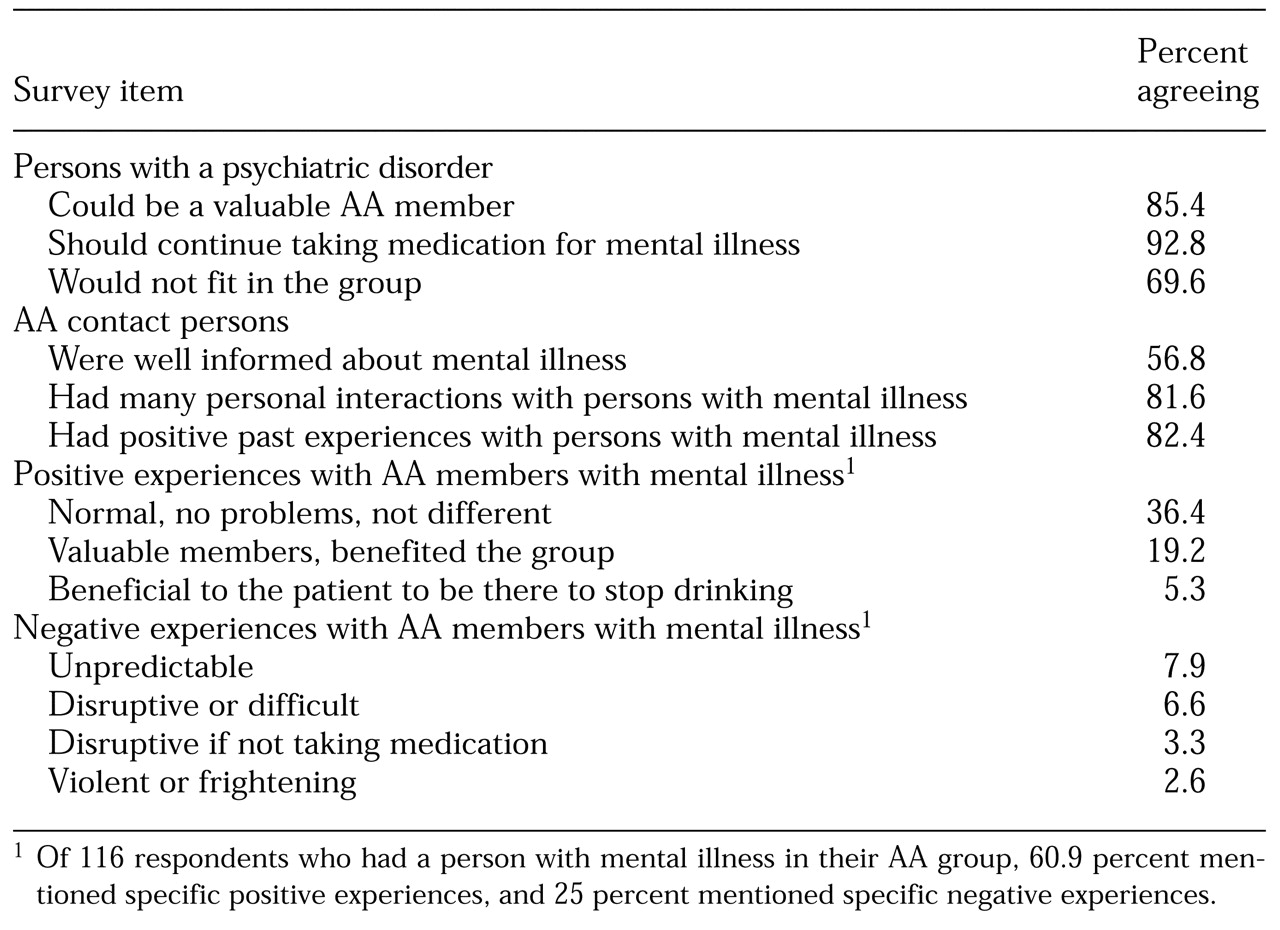

More than 85 percent of the 125 AA contact persons we surveyed exhibited positive attitudes toward persons with mental illness, agreeing (43.2 percent) or strongly agreeing (42.4 percent) that they could be valuable group members (see

Table 1). A majority (57.6 percent) indicated their group would welcome persons with mental illness. Most (81.6 percent) said they had many interactions with mentally ill persons, and most were positive experiences (82.4 percent). More than half (56.8 percent) agreed they were at least relatively familiar with the technical aspects of mental illness. A total of 92.8 percent of the respondents believed that persons with mental illness should continue taking their prescription medication.

The attitudes of AA contact persons toward those with mental illness appear to be based, in part, on positive experiences. Of the 125 contact persons interviewed, 116, or 93 percent, reported having a member with mental illness in their group at some time. Of those 116 respondents, 60.9 percent reported substantially positive experiences with those members, and 25 percent reported negative experiences. More specifically, 36.4 percent of respondents described the individual with mental illness as "not being so different" and indicated they had caused no particular problems; and 19.2 percent of the respondents described individuals with mental illness as valued group members. Negative experiences mentioned by respondents included the mentally ill individuals' unpredictability (7.9 percent), tendency to be difficult (6.6 percent), and tendency to be disruptive if they did not take their medication (3.3 percent).

Despite the positive attitudes, 69.6 percent of the respondents indicated that persons with mental illness would not fit well in their AA group. Fifty-four percent considered a group specifically for persons with dual diagnosis to be a better alternative. These responses perhaps reflect the tendency of self-help groups to be more homogeneous than heterogeneous. For example, Humphrey and Woods (

7) found that African-Americans who attended an AA group predominantly made up of other African-Americans were significantly more likely to be involved one year later. The availability of AA groups consisting of others with mental illness could have a similar effect on long-term membership of individuals with mental illness.

Discussion and conclusions

Accounts of persons with a mental illness who do not feel welcome at AA groups may not be based on the group's unwillingness to involve them but rather on a mutual feeling that the match may not be good. As Carey (

8) has suggested, individuals with a dual diagnosis should search for the AA group with the right "personality." This search is necessary because not enough dual diagnosis groups are available to permit regular attendance, and those who attend AA programs regularly have a better chance of maintaining sobriety. O'Connell (

9) has encouraged providers to discuss patients' fears about the group, prepare them for meetings, and actually attend group meetings with them.

Almost all of the AA contact persons we surveyed indicated that a member with a psychiatric disorder should continue taking medication, in sharp contrast to much anecdotal information about advice received at AA meetings to stop medication. Since the early 1980s, AA has widely distributed a pamphlet on medications and other drugs that recommends involvement of a physician and continued use of prescribed medication (

10). The data presented here suggest that encouragement to stop taking psychiatric medication may have become much less a problem in recent years.

Most of the survey respondents indicated that their groups have had members with mental illness. Although these members were welcome, many AA contact persons believed that dual diagnosis groups would be more appropriate. Several such groups already exist, and some models have been created for the development of dual diagnosis groups within the mental health system—for example, Mentally Ill Chemical Abuser (MICA) groups (

9). It is hoped that experience in such groups will provide people with mental illness with information about AA-type groups and will allow them to develop confidence in using the AA group format. Traditional AA groups may be most useful as part of long-term strategy to prevent relapse.

AA contact persons may be more knowledgeable and have more progressive attitudes about mental illness than AA's general membership. Future research should examine the attitudes of AA members and whether these attitudes are consistent with their behavior toward persons with mental illness. Research should also focus on persons with mental illness who have become successful AA members. Such information would be useful to ongoing efforts to encourage those with a dual diagnosis to routinely use AA groups.