The introduction of atypical antipsychotics, including clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine, has improved the treatment of patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Clozapine has been shown to improve positive and negative symptoms and impaired cognition among patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (

1,

2). In addition, it has been associated with relapse-free community survival and improved psychosocial functioning at two-year follow-up (

3).

Risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine also have proven efficacy against positive and negative symptoms in inpatient and outpatient treatment settings (

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9). However, their efficacy in outpatient maintenance treatment of patients with severe and persistent mental illness is not as well understood (

7). The study reported here examined the effect of risperidone in outpatient maintenance treatment.

Methods

Subjects were 19 Caucasian men and women aged 18 to 65 years with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. They were recruited from the day treatment program of a state hospital in New York State during a 16-month period in 1994-1996. All 19 suffered from treatment-resistant conditions, and all experienced persistent positive and negative symptoms despite multiple trials of standard antipsychotic agents, including adjunctive pharmacotherapy with antidepressants and mood stabilizers.

The patients were started on risperidone, and their doses were titrated slowly upward while their doses of standard antipsychotic medication were gradually decreased, to discontinuation if possible. Adjunctive medication, such as antidepressants and mood stabilizers, was gradually reduced to the lowest maintenance dose or was discontinued. The treatment team made medication decisions based solely on clinical considerations.

The patients were assessed at baseline and every three months for up to 14 months using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI), and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). All assessments were performed by the first author. Patients needed to complete a minimum follow-up time of three months to be considered a study completer.

Numerical values are presented as means with standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was done using the two-tailed Wilcoxon's signed rank test with the Bonferroni correction factor for multiple tests on the same data set.

Results

Of the 19 subjects, nine did not complete the study. Four dropped out due to psychotic relapse, four due to side effects, and one due to treatment noncompliance. All dropped out before the first outcome testing was performed at three months.

At baseline, the mean±SEM age of the nine patients who did not complete the study was 36.6±2 years. Five of the patients were male, and four were female. They had been ill for a mean of 17.3±1.2 years. The ten study completers—eight men and two women—had a mean±SEM age of 37.1±2.8 years. They had been ill for a mean of 19.2±1.7 years.

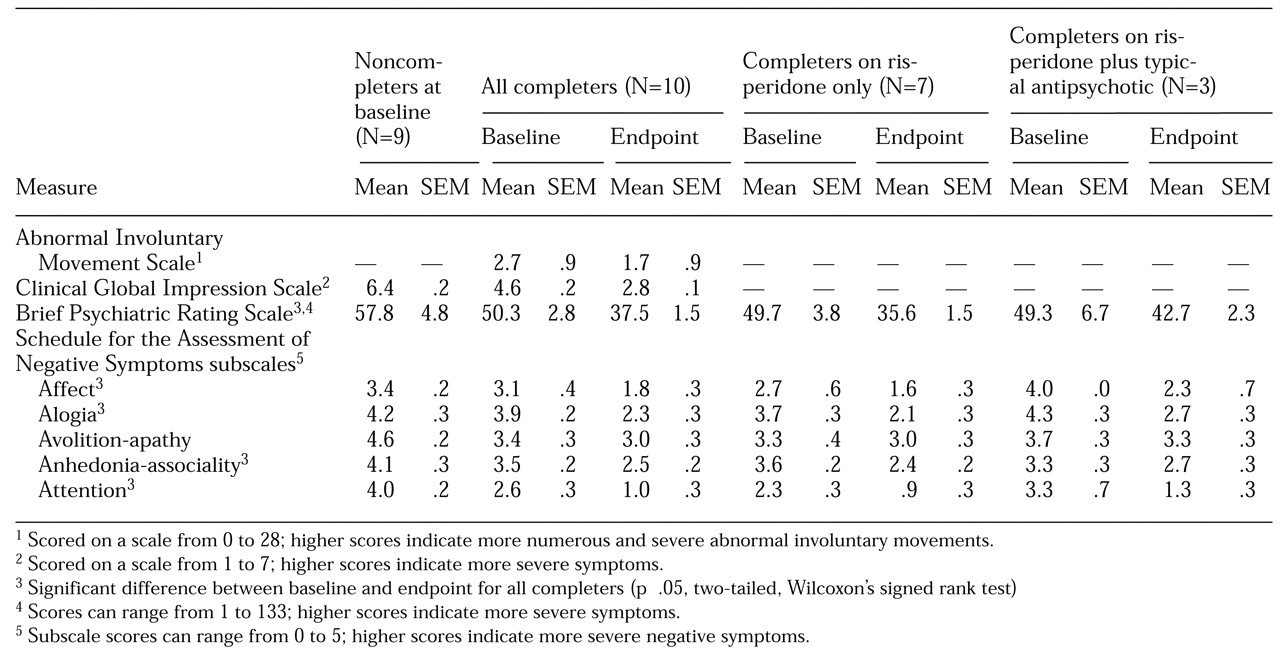

Compared with the ten patients who completed the study, the noncompleters had been hospitalized twice as often—a mean of 17 hospitalizations, compared with eight for the completers. The noncompleters also exhibited more severe symptoms at baseline (see

Table 1). Their baseline mean CGI score of 6.4 was in the range for severely ill to most extremely ill patients, and their scores on the SANS subscales for avolition-apathy and for attention were in the marked range, indicating severe negative symptoms. The two groups did not differ in dosage of medication in chlorpromazine equivalents at baseline (1,111±351 mg for the noncompleters and 1,337±418 mg for the completers). However, both groups had substantial prior exposure to neuroleptics. The difference in AIMS scores between baseline and the end of the study shown in

Table 1 reflects the fact that the group of treatment completers included all patients in the sample who had tardive dyskinesia at baseline.

Of the four noncompleters who experienced psychotic relapse, three improved on clozapine, as evidenced by a reduction in BPRS scores of 20 percent or more. One had previously taken clozapine and relapsed early in the risperidone titration period. The fourth patient was rehospitalized for six months and needed high doses of depot prolixin with atypical-antipsychotic augmentation.

Four other noncompleters experienced side effects. Of the two with akathisia, the first did well when returned to the typical antipsychotic she had taken before the risperidone trial. The second was placed on clozapine, developed neuroleptic malignant syndrome during titration, and was medically hospitalized. Use of a typical antipsychotic plus increased support allowed the patient to achieve tenuous outpatient stabilization. A third patient, who experienced vomiting when placed on risperidone, did well when returned to his pre-risperidone therapy. The fourth patient, who was allergic to risperidone, responded to clozapine, as evidenced by a reduction in the BPRS score of 20 percent or more.

The ninth patient who did not complete the study was noncompliant with treatment and was hospitalized. It is important to note that the two patients who did well when returned to their typical antipsychotic therapies were less severely ill than the other seven noncompleters.

Outcome testing for the ten completers indicated significant improvement over baseline in the BPRS score, SANS subscale scores (except for avolition-apathy), and the CGI (see

Table 1).

The total dose of risperidone prescribed was 4 mg to 12 mg per day (mean of 8.2±.7 mg) administered in two divided doses. Patients on risperidone experienced diminished extrapyramidal symptoms, leading to a decreased need for or discontinuation of anticholinergic agents. Among treatment completers, weight gain—of 5 kg or less—was the only significant side effect. Of the four completers who used adjunctive antidepressant or mood stabilizer medications before the study, only one required an antidepressant with risperidone.

Three of the ten completers required adjunct typical antipsychotics. These patients tended to be more ill at baseline and less responsive to pharmacotherapy, especially as evidenced by their score on the SANS avolition-apathy subscale.

Discussion

This naturalistic study found that risperidone was effective in reducing both positive and negative symptoms in long-term maintenance treatment of about half of a sample of 19 patients with severe and persistent mental illness. Although the bulk of improvement in negative symptoms for these patients occurred within the first three months, gradual improvement continued for 14 months. Positive symptoms improved over the first three months. No further improvement occurred thereafter.

The risperidone-only group, which had significant but not severe positive and negative symptoms at baseline, improved in both spheres. Patients who received risperidone plus typical antipsychotics improved as well but not to the same extent. These patients had more severe negative symptoms at baseline, particularly avolition-apathy, which remained marked despite vigorous pharmacotherapy. Finally, noncompleters were the most ill and showed the poorest response to risperidone. These findings are consistent with the known association between increasing levels of symptom severity, particularly of negative symptoms, and poorer outcome (

10).

Risperidone appears to have a low incidence of tardive dyskinesia and may reduce preexisting tardive dyskinesia (

4). In the study reported here, the AIMS score diminished in the risperidone-only group (all patients with tardive dyskinesia were in this group). Because the abnormal movements measured by the AIMS improved within the first three months of the study, the improvement is more likely secondary to withdrawal of the typical antipsychotic than to a direct effect of risperidone. Nevertheless, the absence of de novo emergence, or worsening, of preexisting tardive dyskinesia argues for consideration of the use of risperidone in treatment of patients with tardive dyskinesia who are being maintained on typical antipsychotics.

The shortcomings of this study include its modest sample size and the absence of a blind rater and a distinct control group, although patients served as their own control subjects.

Conclusions

Risperidone is effective for long-term treatment of patients with serious and persistent mental illness that is treatment resistant. Its use is associated with improvement in both positive and negative symptoms as well as in preexisting tardive dyskinesia. In addition, risperidone may be less likely to produce tardive dyskinesia, compared with typical antipsychotics. Risperidone is recommended for patients with moderately high levels of positive and negative symptoms, particularly if vigorous trials of standard antipsychotics have been ineffective, and for patients with tardive dyskinesia. For patients with more substantial negative symptoms, combined pharmacotherapy may be helpful, provided tardive dyskinesia is absent. However, for patients with severe positive and, especially, negative symptoms, clozapine continues to be the gold standard, and a trial of clozapine is warranted for the most impaired, chronically psychotic patients.

This pilot study suggests the need for larger studies to test the effectiveness—as opposed to the efficacy—of the atypical agents such as risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine in the long-term treatment of patients with serious and persistent mental illness.