Since 2002 more than 1.8 million troops have served in Operation Enduring Freedom-Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF-OIF). Twenty percent or more of these soldiers have psychiatric symptoms, 18% have difficulty holding a job, and large numbers experience family difficulties (

1). Major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are two of the most common mental disorders studied among returning OEF-OIF soldiers. Serving the diverse needs of these veterans remains a challenge. Factors such as the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment (

2) and fragmented resources within a complex service delivery system contribute to a great deal of unmet need.

A number of studies have begun to document the extent of mental health concerns and disorders among OEF-OIF veterans (

3–

6). For instance, at three to six months after returning from deployment to Iraq, 17% of active duty soldiers and 25% of reservists screened positive for PTSD and 10% of active duty soldiers and 13% of reservists screened positive for depression (

7). In a large database study of OEF-OIF veterans enrolled in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care, 13% had a diagnosis of PTSD, 5% had a diagnosis of depression, and another 5% had a diagnosed substance use disorder (

8).

Reintegration into civilian life, including gainful employment, is important to the mental, social, and financial well-being of adults. Even before the current economic collapse, reservists and National Guard soldiers had difficulty reintegrating into their previous employment, and discharged soldiers struggled to find new employment. Difficulty finding and keeping a job or maintaining an adequate level of job performance may reflect the effect of multiple deployments that disrupt continuous employment, the increasing level of strain on workers in the current economic climate, psychiatric illness, and other factors.

Because large numbers of returning soldiers have a diagnosis of depression, it is reasonable to assume that it may be one of the underlying contributors to employment problems. Research in the civilian population has identified depression as a source of multiple employment problems (

9–

12). Depression is costly both to employees with the condition and to their employers. Even though greater attention has been focused on improving the quality of care for depression and other psychiatric conditions, many people still do not get the care they need. Complicating matters is the fact that medical care, even when excellent, does not necessarily reduce depression's adverse impact on workers and their employers. In a recent literature review, Lerner and Henke (

13) chronicled the large toll that depression takes on employees, families, employers, and the nation's economy. Compared with workers without depression, employees with depression suffer more job loss, job turnover, premature retirement, work absences, on-the-job limitations (reductions in at-work productivity known as presenteeism), and disability. In the United States, the estimated cost of this loss is between $36 billion and $51.5 billion annually (

10,

14). Nonetheless, a body of research has accumulated that offers some potential solutions for preventing, detecting, and treating depression-related work problems of OEF-OIF soldiers (

15).

In addition to the burden of depression, PTSD is common among returning OEF-OIF soldiers. Although the impact of PTSD on work functioning is an underinvestigated area, there is some initial evidence that OEF-OIF veterans who screen positive for both diagnosis-level and subthreshold PTSD symptoms are more likely than those without significant PTSD symptoms to have multiple employment difficulties, including problems finding a job, difficulty with coworkers, and more missed work days in the past month (

16,

17). These findings of impaired work functioning are similar to those in civilian samples with PTSD (

18).

This study provides the first picture of work performance problems among OEF-OIF veterans enrolled in VA health care. Most OEF-OIF veterans return to the civilian workforce, and their mental health problems and other readjustment issues are likely to contribute to work impairment. It is our hope that identifying impairments in work functioning will contribute to development of interventions to enable this population to maintain employment, a mainstay of self-esteem and purpose. In conducting this study, we hypothesized that both depression and PTSD would be associated with significant impairment in work functioning.

Methods

Study setting and patients

Data from 797 OEF-OIF veterans referred by their primary care providers for further mental health assessment were derived from structured interviews conducted between August 2007 and April 2009 by behavioral health laboratories (BHLs) at the Philadelphia, Lebanon, and Pittsburgh VA medical centers in Pennsylvania, the Perry Point and Baltimore VA medical centers in Maryland, and VA medical centers and outpatient clinics in the VA Healthcare Network of Upstate New York. This study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating VA medical center, which determined that individual informed consent was not required because only deidentified clinical data were used. Only patients self-identified as OEF-OIF veterans (had served in at least one of 11 countries considered combat zones after September 11, 2001) were included in the analyses. OEF-OIF status was confirmed by information listed in the electronic medical record. All OEF-OIF veterans are considered to have been subjected to ongoing life threat and threat of physical harm because of consistent imminent danger posed by terrorist acts, civil insurrection, hostile enemy fire, and harsh war conditions.

The BHL is a flexible and dynamic clinical service that is available at several VA facilities and is designed to help manage the behavioral health needs of patients seen in primary care (

19). Primary care providers refer patients who need further behavioral health assessment to the BHL. The most common reason for referral is that a patient has screened positive on a measure for depression, PTSD, or alcohol misuse, which each veteran enrolled in the VA health system receives annually. A trained mental health technician contacts patients in person or by telephone and delivers a brief, structured interview. After the interview, the primary care provider is given a comprehensive report of the patient's mental health and substance misuse symptoms and degree of physical, social, and work impairment. This feedback is meant to guide the primary care provider in treatment planning, including referral to collaborative care management and specialty mental health or substance use treatment as needed.

Measures

The core BHL assessment includes several empirically validated measures and targeted symptom-specific questions to assess a wide range of psychiatric disorders and symptoms. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (

20) is used to provide a provisional

DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression as well as a depression severity score. Possible PHQ-9 scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater depressive severity. The PTSD Checklist (

21) is used to assess PTSD symptom severity and identify symptoms consistent with a PTSD diagnosis. Possible scores range from 17 to 68, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The International Neuropsychiatric Interview (

22) is used to establish diagnoses for panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and alcohol abuse or dependence. The number of binge drinking episodes in the past three months, defined as having five or more drinks in a single day, was assessed. A screen for illicit drug use probed for repeated use of illicit drugs.

Participants were considered to be at high risk of suicide if they responded affirmatively to a question about whether they had thought about, seriously considered, or attempted suicide in the past year. A single question was used to assess whether a participant had “ever experienced a significant head injury.” A single question also inquired whether the participant took “any medications, prescribed or not, for depression, anxiety, or nerves” within the past month. The mental component score (MCS) and physical component score (PCS) of the Short-Form Health Survey of the Medical Outcomes Study (SF-12) (

23) were used to measure general physical and mental functioning. Possible scores for both SF-12 measures range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating greater disability.

The Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) is also part of the core BHL assessment. The WLQ is a validated self-report survey for patient and employee populations, including groups with and without depression (

9,

12,

24,

25). Subscales of the WLQ provide work performance information in four areas: mental-interpersonal demands, time management, output (for example, handling the workload and finishing work on time), and physical demands. WLQ continuous scale scores reflect the percentage of time in the prior two weeks that the respondent had job performance deficits because of emotional or physical health problems (presenteeism). The eight-item version has been validated against the full WLQ and used in other studies (

26–

28). It is scored on a scale from 0%, respondent is limited none of the time, to 100%, limited all of the time, with higher scores indicating greater impairment.

The WLQ at-work productivity loss summary score (0%–100%) is calculated from the weighted sum of the four WLQ subscale scores. Specifically, the score reflects the percentage difference in output between employees with work impairment and a benchmark group of employees who have no limitations. The dollar amount lost per year can be calculated by multiplying the productivity loss score by the mean employees' annual salary. Because the actual salaries for individuals were unknown, we used median salaries for the geographic regions. The WLQ has been extensively used in past research, including in studies comparing productivity loss from mental disorders with loss from general medical disorders (

11,

24,

26–

29). The WLQ was administered only to veterans who reported working full- or part-time; therefore, WLQ data are available for a subset of the total sample (N=473).

Analytic plan

Descriptive, univariate analyses included calculations of means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes and frequencies and percentages for categorical outcomes. To compare sociodemographic and background characteristics and BHL assessment outcomes for mental and substance use conditions between the employed and unemployed groups, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Associations between patient characteristics and the four WLQ subscales were evaluated in both unadjusted and adjusted models. Unadjusted associations between patient characteristics and the four WLQ subscales, productivity loss, and cost resulting from presenteeism were evaluated by a series of univariate ANOVAs. To assess the extent to which each mental and substance use condition uniquely accounted for work limitations and productivity loss and cost after adjustment for other sociodemographic, background, and clinical characteristics, we ran a series of multivariate linear regression models. Each of the WLQ subscales and productivity loss and cost were treated as separate dependent variables. Sociodemographic and background variables were entered as covariates in the first step of each model, with clinical conditions entered in the second step. Of note, these conditions were modeled as both continuous predictors (for example, the severity of depression and PTSD symptoms) and categorical predictors (for example, the presence or absence of major depression, PTSD, and generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder) in separate models. However, because the pattern of results was comparable across the categorical and continuous predictor models, the results of the categorical predictor models are presented for ease of interpretation. All analyses were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at ≤.05. Analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics (SPSS), version 17.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the full sample and the two employment status groups. The mean±SD age of the sample was 34±11 years, and most were male (88%). Sixty-three percent of the veterans identified themselves as non-Hispanic white, 41% were married or had a partner, and 19% reported financial distress. Fifty-nine percent were employed. The proportions of Veterans meeting criteria in the BHL clinical assessments were as follows: major depressive disorder, 35%; PTSD, 47%; generalized anxiety disorder, 42%; panic disorder, 8%; and alcohol dependence or illicit drug use or both, 18%. Overall, 71% of the veterans in the sample (N=566) reported at least one disorder. A notable proportion (39%) reported ever having experienced a serious head injury.

Unemployed veterans (41% of the sample) were significantly more likely than employed veterans to be unmarried or unpartnered (p=.03) and to feel that they did not have enough money to get by (p<.001). On the basis of SF-12 component scores, unemployed veterans were also more likely to have problems in mental functioning (p=.03) and physical functioning (p<.001). PHQ-9 scores indicated that unemployed veterans were more likely to have a depression diagnosis (p<.001) and to have more severe depression symptoms (p=.003).

Results from unadjusted, univariate analyses of the relationship between patient characteristics and the four WLQ subscales (mental-interpersonal demands, time management, output, and physical demands) are summarized in a table in an online supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org. These results revealed that with the exception of employment type (full-time versus part-time) and age group, each of the sociodemographic and background characteristics was significantly associated with impairment on at least one of the WLQ subscales. Lower scores on the MCS and PCS were correlated with work impairment on each WLQ subscale and with productivity loss (p<.001 for all). Greater severity of depressive and PTSD symptoms and number of alcoholic binges in the past three months were each associated with impairment in all measures of work productivity (WLQ subscales and productivity loss). Similarly, all psychiatric diagnostic categories—major depression, PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder, and alcohol dependence or illicit drug use—were each significantly associated with impairment on all four WLQ subscales (with reductions in mean raw scores on each subscale ranging from 26 to 47 points) and with greater work productivity loss (mean range 9%–10% loss in productivity).

Table 2 presents results from multivariate linear regression analyses of the relationship between individual predictor variables and the four WLQ subscales; the models controlled for sociodemographic and background characteristics and co-occurrence of mental and substance use conditions. None of the sociodemographic or background characteristics were related to the WLQ subscale mental-interpersonal demands. However, meeting criteria for a diagnosis of major depression (p<.001), PTSD (p=.001), and generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder (p<.001) were each associated with impairment in mental-interpersonal aspects of job performance. After adjustment for all other variables in the model, impairment in time management was associated with having a diagnosis of major depression (p=.001), PTSD (p=.002), and generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder (p<.001); reporting a significant head injury (p=.04); and having a lower SF-12 PCS score (p<.001). Impairment in work output was associated with meeting criteria for major depressive disorder (p=.01), PTSD (p=.01), generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder (p=.001), and alcohol dependence or illicit drug use (p=.01); being male (p=.04); and having a lower PCS score (p<.001). Impairment in physical demands was associated with being married or having a partner (p=.02), reporting a significant head injury (p=.02), having a lower PCS score (p=.01), and having a diagnosis of alcohol dependence or using illicit drugs (p=.01).

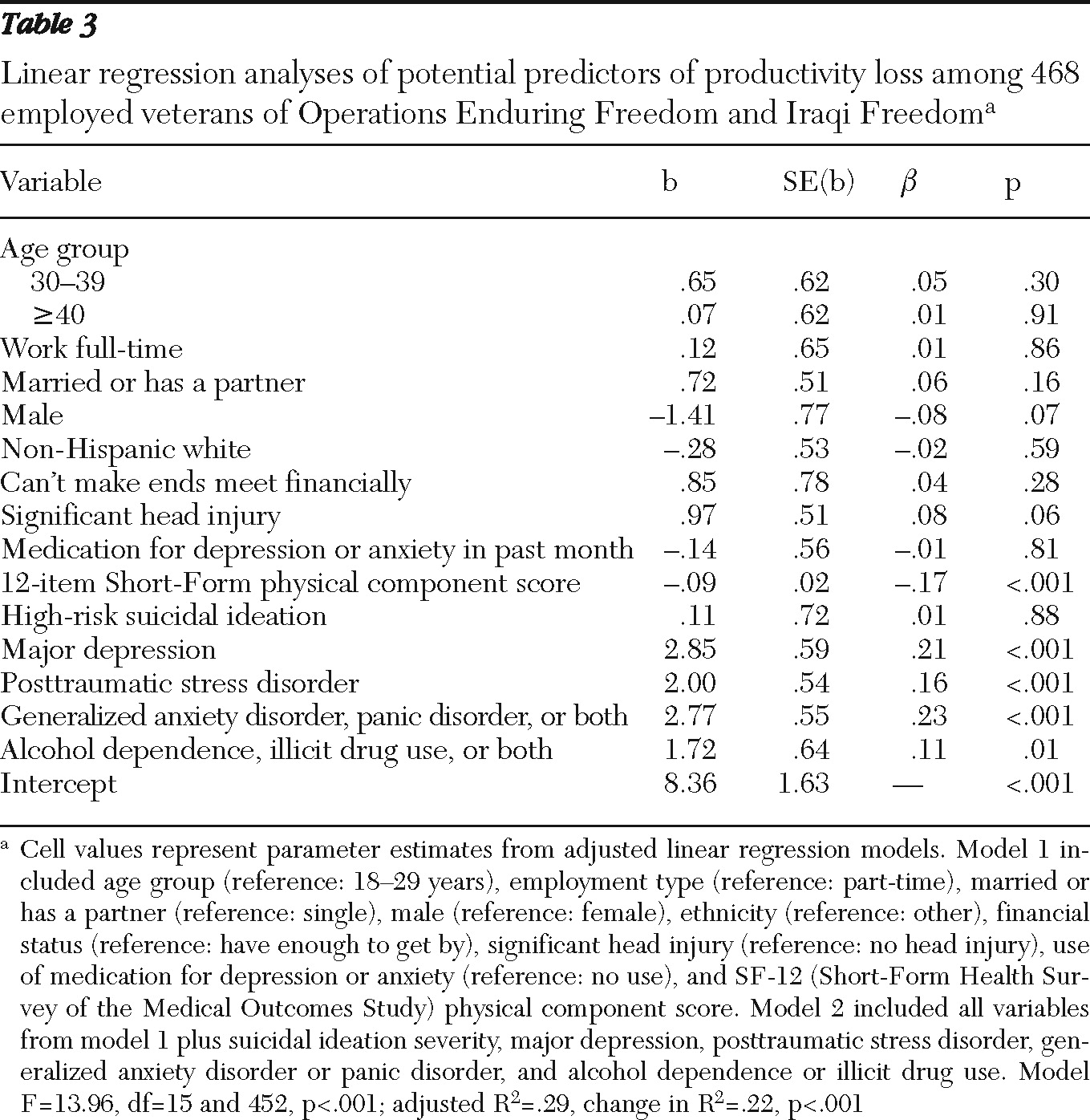

Table 3 shows similar analyses for the fifth outcome variable—productivity loss. After adjustment for all other variables in the model, productivity loss was significantly related to meeting criteria for major depressive disorder (p<.001), PTSD (p<.001), generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder (p<.001), and alcohol dependence or illicit drug use (p=.01) and having a lower PCS score (p<.001). On the basis of median salaries, annual employer costs associated with lost productivity were as follows (compared with veterans who did not have the disorder): for a veteran with major depressive disorder, $929; generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder, $904; PTSD, $651, and alcohol dependence or illicit drug use, $561.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to investigate the relationship between psychiatric status and work impairment among OEF-OIF veterans enrolled in VA health care. Our results demonstrate that the mental health status of veterans returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has a substantial negative impact on their work functioning. In our sample of 797 OEF-OIF veterans referred by their VA primary care provider to receive further mental health assessment, we found high rates of psychiatric and substance use disorders. When analyses controlled for demographic characteristics, several variables were significantly and independently associated with impairment in multiple dimensions of job performance and with productivity loss and productivity costs. These predictor variables were major depressive disorder, PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder, alcohol dependence or illicit drug use, a history of a significant head injury, and physical impairment as measured by the SF-12.

The 13%–48% loss in productivity reflected in scores on the four WLQ subscales is higher than the 9% loss found for a sample of employed nonveterans with depression (

29) (see online table). However, that study found that productivity loss among depressed employees was four times as great as among nondepressed employees, which is similar to our findings.

Even though we found high rates of mental health problems and work impairment, it is important to recognize the significant degree of resilience among these OEF-OIF veterans. Overall, for 29% of the sample, the BHL interview found no evidence of a psychiatric illness. Unfortunately, unemployment was high in this sample, and it was associated with higher prevalences of depression and other psychiatric disorders.

These results have several important intervention implications. Typically, primary care plays an important role as the first line of assessment and intervention for psychiatric problems. In response, the VA has prioritized the integration of mental health services into the primary care setting to reduce barriers to receipt of high-quality mental health care (

30). The presence of mental health professionals in primary care offers an excellent opportunity to provide clinical intervention as well as ongoing assessment of work impairments. Efforts to integrate behavioral health care and primary care are needed so that primary care and mental health providers, as well as other health care professionals who frequently interact with OEF-OIF veterans, can assess the impact that depression, PTSD, anxiety, substance use, and head injury have on work functioning and can promote interventions as needed.

The VA has established clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression, PTSD, and substance use disorders (

www.healthquality.va.gov) that recommend specific empirically supported pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for these disorders. Examples of empirically supported interventions include the care management strategies for depression, anxiety, and alcohol misuse employed by the BHLs (

19,

31–

33). Implementation of these interventions is an important first step in improving work functioning and reducing disability related to psychiatric disorders.

The VA is continually expanding health care services to meet the needs of OEF-OIF veterans. Combat veterans now receive comprehensive VA health care free of charge for five years after military discharge. All VA medical centers have created a single point of access for new veterans in order to guide them in receiving all necessary VA services. Special programs have also been created for OEF-OIF veterans. For example, a “polytrauma team” uses a multidisciplinary team approach to provide comprehensive services to veterans who have experienced both physical trauma (brain and spinal cord injuries) and psychological trauma (PTSD). The results of this study suggest that the VA should consider implementing systematic assessment of work impairments among OEF-OIF veterans and providing special services to reduce them.

WLQ subscale scores indicated performance deficits in mental-interpersonal demands, time management, work output, and physical demands. The scores provide insights into specific problem areas that may contribute to the development of interventions and approaches to managing job demands, addressing barriers to effective work functioning, and identifying appropriate workplace supports. Work-specific interventions may need to be tailored on the basis of the employee's diagnosis, such as major depression, PTSD, or a substance use disorder. It may also be worthwhile to adapt job retention techniques currently used in employment programs for individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (

29,

34,

35).

Recent research suggests that improving work outcomes may depend on care models that integrate symptom relief and work-focused interventions to help people with depression and other diagnoses improve their ability to work (

15). Further investigation of this area is needed. Such interventions will require new configurations of care professionals that team primary care providers, who see most of the patients, with specialists in work assessment and job design, such as occupational health professionals and employee assistance program counselors. In addition to helping employees with depression and reducing employer burden, new medical and vocational care models may have broader application to the millions of working people with chronic mental health and general medical problems.

Strengths and limitations of this study must be taken into account. A major strength is the use of empirically validated standardized assessments administered by trained mental health technicians. Although our large sample from six different VA health care networks allows us to generalize our findings to OEF-OIF veterans in different geographical locations and in both urban and rural areas, these results are limited to veterans whose primary care provider determined that they needed further mental health or substance abuse assessment. Therefore, our results are not representative of all OEF-OIF veterans; those who do not have psychiatric symptoms may be more resilient. We relied on self-reported productivity, which may underestimate actual lost productivity. In addition, we did not include work absences in the measure of lost productivity, which would result in underestimating the impact on productivity of psychiatric illness. Also, our methods did not allow us to assess veterans' problems with unemployment in detail. Further research on reasons for veterans' unemployment may offer a fuller picture of the impact of psychiatric problems.

Conclusions

Iraqi and Afghanistan war veterans reported significant work impairments associated with depression, PTSD, anxiety, substance use, and head injury. The delivery of empirically supported interventions to treat psychiatric disorders and the development of care models that include employment-specific interventions may improve combat veterans' ability to return to civilian life and reduce work impairment. However, there are few empirically supported models of work interventions that focus on symptoms, and development of such interventions for this population would require adaptation and trials of current models. As the VA continues to try to meet the evolving needs of OEF-OIF veterans, care models integrating interventions for psychiatric symptoms and work impairments should be considered.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was supported by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Integrated Service Network 4 (VISN-4), the VISN-5 MIRECC, the VISN-2 Center for Integrated Healthcare, and the Fisher Fund of the Tufts Medical Center. The authors thank the primary care providers who facilitated care for the veterans in this project.

The authors report no competing interests.