This chapter provides an introduction to the theory, general principles, goals, and structure of good psychiatric management (GPM) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). The chapter ends by underscoring the compatibility of the two approaches and providing examples of how they can work together to inform treatment.

Overview of Good Psychiatric Management

General psychiatric management, or “good psychiatric management” as it was rebranded by John Gunderson, is a principle-driven approach well suited for generalist clinicians treating people with borderline personality disorder (BPD). At its core, GPM relies on fundamental clinical tasks, such as diagnostic disclosure, psychoeducation, and enhancing accountability, to work on reducing and managing BPD symptoms. It additionally provides a theoretical model for understanding, and thereby managing, the symptoms of BPD.

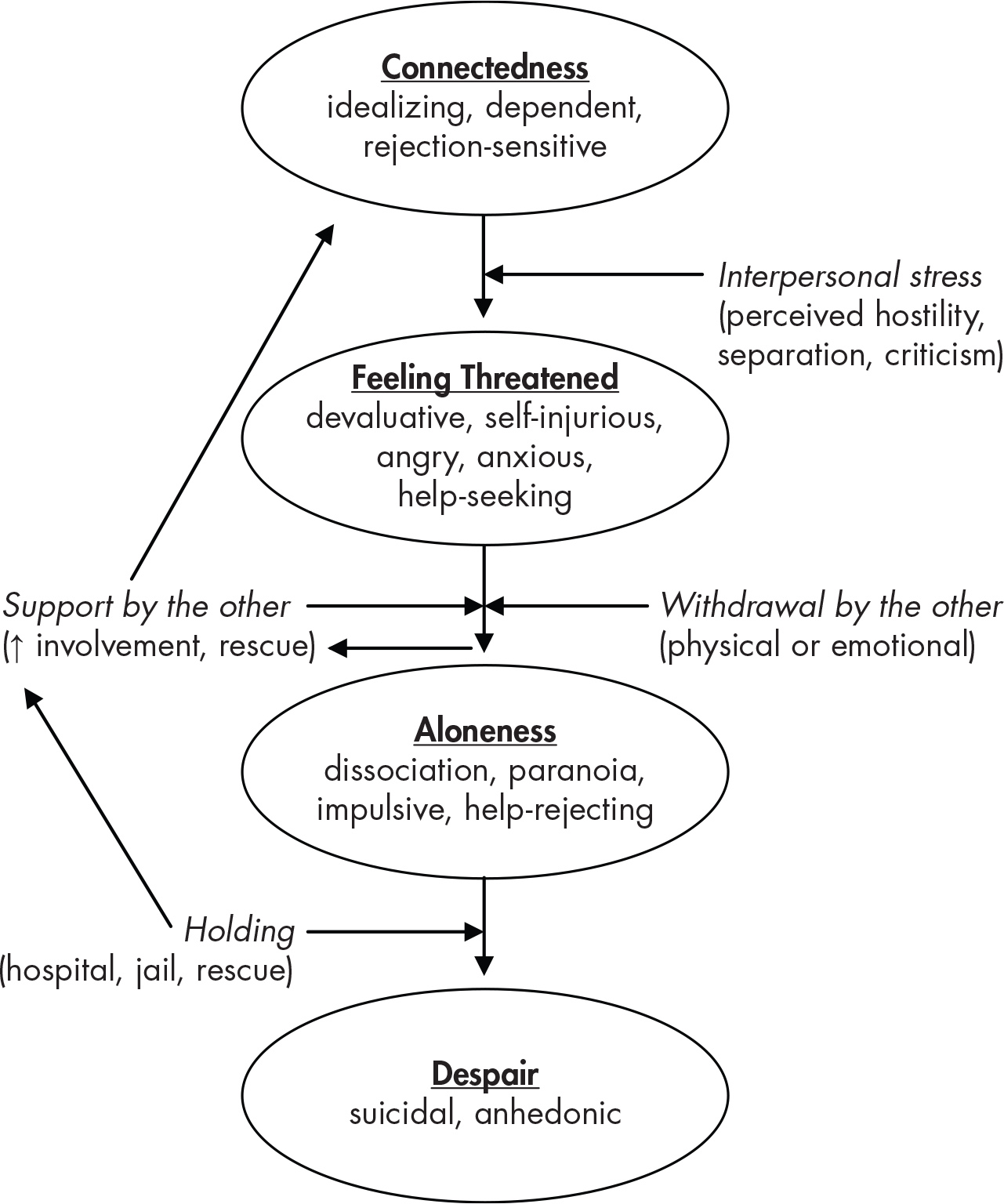

GPM proposes that people with BPD are born with a genetic predisposition to be interpersonally hypersensitive. As a result, people with BPD develop a characteristic interpersonal pattern that can get in the way of building stable interpersonal relationships and can also get in the way of other functional goals related to work and school. This prototypical pattern is illustrated in

Figure 1–1.

When patients with BPD feel connected to others, they are less symptomatic, more effective, and more open to learning, but they also tend to idealize others and are anxiously vigilant for signs of rejection. When they begin feeling interpersonally threatened because of real or perceived rejection, they may start to become angry or devalue others, and their symptoms become more evident. At this point, they are still engaged, albeit angrily. If the patient receives support from others while feeling interpersonally threatened, the patient then returns to the “connected” state. However, if other people withdraw in reaction to the patient’s angry devaluation, this can then lead to increased distress, self-harm, paranoia, dissociation, and impulsive behaviors such as substance use, disordered eating, spending sprees, risky sexual activity, or reckless driving. At this point in the symptomatic cycle, it is difficult to intervene collaboratively, as the person with BPD becomes more difficult to reach through words. If left alone without the containment of a relationship, the patient may descend into hopelessness and suicidal behavior. Often at this point others, including clinicians, family, or friends, might act unilaterally by putting the patient in a safe setting (i.e., in a hospital or on suicide watch). The patient can then reconstitute into a connected state; however, this brings the cycle into a position where others are central to solving problems of safety, a situation that ultimately reinforces problematic dependencies.

The clinician can interrupt this pattern in several ways. One way is to help the patient become aware of the pattern and notice common interpersonal stressors. The clinician and patient can work together to try to intervene when the patient is feeling threatened earlier in the symptom cycle, before the patient begins acting impulsively or feeling hopeless and suicidal. Intervention earlier in the descent toward reckless action or despairing suicidality is crucial because it allows the clinician and patient to collaborate on efforts to understand and problem solve more effectively. The GPM clinician advises the patient to be prepared for inevitable moments of feeling threatened. Together, the GPM clinician and the patient with BPD reduce the likelihood of intolerable loneliness by acting in more prosocial ways that make others want to be with them and by broadening their support system so they are less affected by ups and downs in intense exclusive relationships (e.g., romantic relationships). Self-reliance and reduced dependency on others are encouraged as they can serve as a buffer to the way others’ reactions affect the person with BPD.

In addition to noticing these patterns, the clinician also builds a therapeutic alliance with the patient in which the patient feels connected to the clinician. This therapeutic alliance is enhanced by the clinician’s frank feedback and consistent, responsive, and curious attitude toward the patient. Through the experience of consistently maintaining a reliable “good enough” connection with the clinician, sustained through both appreciative connected and angry devaluing states, the patient’s sense of who they are can become more stable and coherent. Because of this integrated appreciation of these two sides of the person with BPD, the clinician provides at least one relationship that can serve as a “corrective experience” for the patient, one in which the patient experiences being heard and understood, balanced with reasonable expectations of being responsible for themselves and acting in a way that influences others to want to be around them.

The goals of treatment in GPM are to decrease subjective distress and BPD symptoms, while improving social functioning and interpersonal relationships. These are consistent with the general aims of any psychiatric treatment. The structure of GPM is flexible. It generally involves the patient and clinician meeting once per week, depending on the patient’s needs and the clinician’s availability. Attendance by the patient at any type of group available in the community is encouraged. Clinicians are advised to address their intersession availability with patients, and some phone access to the clinician between appointments is recommended, but dependency for safety is regarded with skepticism. Last, clinicians are strongly encouraged to have access to consultation with other clinicians (

Gunderson and Links 2014).

Important elements of GPM include collaboratively providing the patient with a diagnosis and psychoeducation about BPD. In session, clinicians take an active role and focus on the patient’s life outside of therapy. They encourage verbal discussion of the patient’s feelings and interactions with others to stress thinking before acting. GPM emphasizes working with the patient to build a life for themselves and specifies that patients should focus on career and friends first, then romantic partners. GPM also provides guidance regarding managing comorbidities, medications, suicidal behavior and self-harm, hospitalization, working with multiple providers, working with families, and monitoring progress in treatment.

Overview of Dialectical Behavior Therapy

DBT is a manualized therapy designed to treat people with suicidal and self-harming behaviors. It has been studied in many randomized controlled trials and has one of the strongest evidence bases among BPD treatments (

Stoffers et al. 2012). In DBT, the explanatory model of BPD focuses on emotional dysregulation as the core difficulty causing symptoms of BPD.

The biosocial model in DBT states that people with BPD are naturally more emotionally intense and sensitive. Furthermore, they return to their emotional baseline more slowly than the general population. Like most natural phenomena, emotional reactivity is thought to exist on a spectrum, with some individuals being more emotionally reactive, others being less emotionally reactive, and most being somewhere in the middle.

Being emotionally intense is not necessarily problematic in itself. There are many emotionally intense people who lead satisfying productive lives. The problem occurs when emotionally intense people grow up in an environment that may not be the best fit for them and they lack skills to manage that mismatch. For example, if an emotionally intense child grows up with parents and siblings who are not as emotionally intense as the child, these family members might not understand the child’s emotional reactions very well and therefore might be prone to respond to the child in a way that intensifies rather than soothes negative emotions.

For instance, when watching a sad movie, other children in a family might be somewhat sad, whereas the emotionally intense child might start crying and take a long time to stop. Parents might naturally say, for example, “It’s only a movie. Don’t worry, calm down. Stop crying so much.” Though reasonable, this attempt at emotional support actually conveys to the child that the child’s response is abnormal and that the parent does not understand the child’s emotional experience. In DBT, responses that convey a lack of understanding of someone’s experience are called “invalidating” responses. In the above example, a more “validating” response might be to hug the child and say, “I know, it’s a sad movie, right?”

DBT proposes that when emotionally intense people are exposed to repeated invalidation or to severe forms of invalidation, such as abuse or neglect, they can develop core symptoms of BPD. Repeated invalidation of a person’s experience can lead the individual to start questioning their own judgment and emotional experience. This inability to trust one’s own experience can lead to one of the core features of BPD: an unstable sense of self. In an invalidating environment, individuals also have more difficulty learning to regulate their emotions, leading to further emotional dysregulation. This is often followed by the development of problematic coping behaviors such as self-harm, substance use, binge-eating behaviors, reckless driving, and other risky behaviors. It is not surprising that with the combination of an unstable sense of self and emotional dysregulation, individuals with BPD frequently have unstable interpersonal relationships. High levels of emotional dysregulation and difficulties with sense of self may also result in dissociation and paranoia in stressful situations. DBT involves learning skills that enable individuals to better manage emotional intensity and emotional dysregulation. Management of invalidation is also introduced and explicitly addressed within the treatment.

When initially developing DBT, Marsha Linehan first used cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) type techniques with suicidal patients, such as teaching them effective problem-solving strategies (

Linehan and Wilks 2015). This approach was experienced as quite invalidating and resulted in clients becoming angry with therapists and dropping out of treatment. She then tried a therapeutic approach that focused mostly on validating the patient’s experience, similar to Rogerian person-centered therapy. Although patients felt understood, steps toward reducing self-harm and building a life worth living did not occur. The synthesis of these two approaches resulted in DBT, which incorporates both change-oriented strategies, such as those seen in CBT, and validating acceptance strategies, such as those seen in person-centered therapy. This synthesis balances understanding with accountability for change in a way that seems to work particularly well in helping people with BPD to build a life worth living and to stop engaging in self-harm behaviors. What is dialectical about DBT? A dialectic involves two opposing poles that may appear to be incompatible with each other but are both true at the same time. Awareness of these poles can provide a more comprehensive perspective, and sometimes the poles can come together, resulting in a synthesis. As alluded to above, the key dialectic in DBT is that of acceptance and change. For example, DBT posits that people with BPD are doing the best that they can (acceptance). It also posits that they can do better (change). Although these two things appear to be in opposition, both can in fact be true at the same time and can come together in a synthesis: People with BPD are doing the best they can, and they can do better (

Linehan 1993, pp. 106–108). Understanding the concept of dialectics can be useful to reduce all-or-nothing, black-and-white thinking, which is common in BPD.

Similar to GPM, the main goal of treatment in DBT is to help the patient build a life worth living. To help the patient attain this goal, DBT prioritizes intermediate goals, including stopping self-harm and suicidal behaviors, reducing behaviors that interfere with effective participation in therapy (e.g., nonattendance, lateness), and stopping other behaviors that the patient finds diminish their quality of life (e.g., substance use, binge eating). Standard DBT consists of 1 year of weekly individual therapy, weekly skills group training, after-hours skills coaching, and a therapist consultation group. DBT involves providing psychoeducation about the diagnosis as well as helping the patient identify prompting events and reinforcers of unwanted behaviors. It involves active problem solving and troubleshooting around different ways to change behavior. Finally, DBT involves learning skills to respond more effectively in situations that provoke strong emotion. Throughout therapy, the clinician’s stance remains grounded in the dialectic of acceptance and change.

Integrating Principles From the Two Approaches

The theories of BPD proposed by DBT and GPM are not incompatible. DBT focuses on the broader concept of emotional dysregulation. In DBT, clinicians work with the patient to identify antecedents leading to dysregulation, which then leads to behavior that the patient considers problematic. The patient and clinician then use collaborative problem solving to identify ways the patient could respond more effectively next time. GPM highlights that one of the common sources of distress for people with BPD is difficulties in relationships, so when a clinician is working with a patient to determine what preceded distress and BPD symptoms, it is useful to consider the possibility of an interpersonal event. In addition, using GPM’s interpersonal model to highlight common patterns can be helpful for patients. For example, by highlighting that many people who are interpersonally sensitive find that they feel threatened when faced with perceived interpersonal rejection, the clinician can help to normalize this reaction for patients and to mark this as something to focus on in treatment. When a patient notices anger, anxiety, or an urge to self-harm, they might then contemplate whether there was a perceived rejection or whether some other type of event has triggered this shift. The patient can then choose how to proceed, possibly using skills to react effectively in a way that is consistent with their values and goals. In this way, the underlying theories of DBT and GPM can work together quite well to inform treatment.