The inception of the consumer-survivor movement in the 1980s challenged thinking about what it means to recover from a serious mental illness. Before this time, recovery had been conceptualized primarily in terms of functional outcomes. Functional recovery encompasses how well people manage their daily lives and engage in activities related to independent living, social relationships, and occupational functioning; some also consider symptom remission or a significant reduction in symptoms as an indicator of functional recovery (

1). There is significant literature examining changes in functional recovery over time both naturalistically and in response to antipsychotic and psychosocial treatments (

2–

5).

The consumer-survivor movement called attention to person-oriented indicators of recovery, such as the degree to which individuals feel empowered, hopeful, and optimistic; the manner in which people view themselves and their capabilities; and their perspectives about their own circumstances (

6,

7). Thus, person-oriented recovery is conceptualized not simply in terms of symptom remission but as a process in which people are able to move past the challenges presented by mental illness to live rewarding, fulfilling lives (

8). There is a growing literature describing interventions to help consumers with serious mental illnesses develop agency, increase empowerment, and feel hopeful about their lives and highlighting how transformation in the culture and services offered by mental health programs can serve to promote important aspects of recovery (

9,

10). This work is promising in its emphasis on putting the principles of the consumer-survivor movement into practice.

As expanded definitions of recovery have taken hold and the recognition of recovery as an intervention outcome has expanded, new tools to measure person-oriented recovery have been developed and validated (

11–

15). These measures assess dimensions of recovery such as connectedness to others, confidence and purpose, and goal and success orientation. There is also increasing interest in and use of instruments that have not been labeled as measures of recovery per se but that capture conceptually related constructs (hope and empowerment, for example) (

16).

This proliferation of measures allows for quantitative evaluation of the ways in which person-oriented recovery may change over time and factors that may be related to these changes. For example, an emerging literature has begun to uncover ways in which person-oriented and functional recovery may be associated longitudinally. Green and colleagues (

17) found that psychiatric symptoms, general health, perceived strengths and barriers, and psychiatric medication usage differentiated participants with serious mental illnesses who had been grouped into recovery trajectories (high, low, increasing, and decreasing) on the basis of factor analysis of scores on a range of person-oriented and functional recovery measures.

Jørgensen and colleagues (

18) demonstrated that person-oriented recovery was related to psychiatric symptoms at four time points over the course of one year. A path analytic study identified negative emotion, self-esteem and hopefulness, and symptoms and functioning as longitudinal predictors of person-oriented recovery (

19). However, because of inconsistencies across studies and the relatively sparse literature in this area, additional research is needed to clarify factors that may limit or enhance person-oriented recovery over time, including but not limited to functional recovery. On the basis of cross-sectional studies, these might include sociodemographic factors, such as age (

20), or degree of participation in personally meaningful areas in the community (such as leisure and employment) (

21,

22).

An especially important question is whether person-oriented recovery improves when individuals are engaged in recovery-oriented mental health services. According to a qualitative analysis of international documents offering recovery-oriented practice guidance, services are recovery oriented if they strive to support community integration; operate within organizations that adopt and support a recovery vision; focus on and adapt to consumers’ personal goals, needs, and strengths; and emphasize partnership in the working relationship (

23). Early work in this area using small convenience samples has provided some evidence that persons with serious mental illnesses experience positive changes over time in person-oriented recovery when they are involved in recovery-oriented psychiatric rehabilitation and other types of recovery-oriented services (

24–

26).

As models of person-oriented recovery have developed and recovery-oriented interventions have been more systematically studied, this literature has expanded to include naturalistic, single-group, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have followed larger samples of people with serious mental illnesses over time and assessed them with validated quantitative measures of recovery and related constructs. This proliferation of studies creates an ideal opportunity to collectively assess the impact of participation in recovery-oriented treatment as well as explore intervention-related and other variables that may moderate treatment gains. For example, the availability of peer support, or support provided by people who have successfully lived with a serious mental illness (

27), is often considered a hallmark of recovery-oriented care (

28). Although studies comparing the effectiveness of services provided by peer versus nonpeer staff exist (

29,

30), additional research is needed to determine the effect of type of service provider on person-oriented recovery.

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to synthesize findings pertaining to the study of person-oriented recovery over time and concomitants of associated change. First, we reviewed RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, and observational studies that assessed person-oriented recovery, hope, or empowerment over at least two time points using a quantitative measure. The systematic review served to provide a descriptive summary of the characteristics of such studies so that the state of the current literature could be appraised. We then conducted a meta-analysis of RCTs to determine whether there were changes over time in person-oriented recovery, empowerment, or hope among individuals participating in recovery-oriented treatment compared with those participating in waitlist or other control conditions. The meta-analysis was also used to examine whether individual characteristics, intervention characteristics, or methodological factors moderated differences in person-oriented recovery constructs over time between groups.

Methods

Methods for Systematic Review

The review process was based on guidelines provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews for Interventions (

31). Multiple systematic searches up to February 2017 were conducted by using PubMed and PsycINFO. These databases were selected because of their comprehensive indexing of biomedical, behavioral, and social sciences literature from psychology and other health care–related fields. The following search terms were used as keywords: “longitudinal” and (“serious mental illness” or “schizophrenia”) and (“recovery” or “empowerment” or “hope”). The reference lists of articles fulfilling all criteria were also hand-searched for other potential studies. Authors of included studies were contacted and invited to share any other published or unpublished studies that might meet criteria for the review.

Articles were included in the review if they met all of the following criteria: article was written in English; study included a quantitative measure of person-oriented recovery, hope, or empowerment; assessments were conducted at two or more time points; and all participants had a diagnosis of a serious mental illness (a mental health condition associated with significant functional impairments such as a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, or severe forms of depression) (

32). A subset of articles that described RCTs of recovery-oriented interventions, meeting previously specified criteria (

23), were included in the meta-analysis. [A description of the search process is available as an

online supplement to this review.]

Data extraction.

The lead author and either the second or last author independently extracted data pertaining to each study, including sample characteristics (age, gender, race, and recruitment setting), study characteristics (study design, sample size, country, and length of follow-up period), intervention characteristics (intervention duration and frequency of meetings, type of intervention provider, mean number of treatment sessions attended, intervention mode and format, and targeted outcomes), and methodological factors (risk of bias and type of comparison group). When discrepancies could not be resolved, and in cases of missing data, study authors were contacted for more information.

Risk of bias and study quality.

The first and last authors independently evaluated risk of bias for each study on the basis of the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool (

33). Use of this tool has been encouraged to assist consumers of systematic reviews in understanding the ways in which the limitations of included studies may bias results (

33). All discrepancies were resolved by discussion until ratings were in 100% agreement.

Methods for Meta-Analysis

Data extraction.

The lead author and either the second or last author also independently extracted data needed for effect size calculation from each study. Much of the data extracted as part of the systematic review process were also used in moderator analyses.

Moderators.

Moderator variables were selected on the basis of substantive considerations and the availability of data across studies included in the meta-analysis. Because the literature on predictors of person-oriented recovery is modest, we considered moderator analyses to be exploratory.

Individual characteristics.

Putative individual characteristic moderators included age, gender, race, and recruitment setting. Data for age were taken from the mean ages of participants across conditions in each study. The percentages of male participants and white participants were calculated for each study. Recruitment setting was categorized as inpatient, outpatient, or both.

Intervention characteristics.

Potential moderators pertaining to characteristics of the study interventions included intervention duration (in weeks), type of intervention provider (mental health professional [such as a nurse or therapist], peer provider [that is, a trained mental health service provider with lived experience of a mental health condition] [

34], or both), mean number of treatment sessions attended, and mode of intervention (individual or group).

Methodological factors.

Type of comparison group (waitlist control or active treatment) served as a potential methodological moderator.

Effect size calculation.

It is recommended that meta-analysts aggregate effect sizes for multiple outcomes from the same participants to obtain the most precise estimates (

35). Therefore, within-study effect sizes for person-oriented recovery, empowerment, and hope outcomes were aggregated with the MAd package for R (

36) by using a method described by Borenstein (

37), which accounts for correlations among the outcome measures. Hedges’ g standardized mean difference effect sizes were calculated, which provide a more accurate estimate of the variance of the effect size when sample size is small (

38), as was the case for a few of the included studies. Effect sizes at postintervention and follow-up were assessed.

Sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analyses were performed with outlier and influential case diagnostics that excluded one study at a time. These included the externally Studentized residual, difference-in-fits value, Cook’s distance, covariance ratio, leave-one-out amount of (residual) heterogeneity, and leave-one-out test statistic for the test of (residual) heterogeneity (

39). These analyses ensure that outliers and other extreme effect size values do not distort meta-analytic conclusions (

39).

Statistical procedures.

Effect sizes and continuous moderator variables were examined for skewness. Because of some skewness in effect sizes, random effects models using DerSimonian and Laird estimation were performed (

40). Heterogeneity of effect sizes was evaluated using the Q statistic and I

2 (

35). These indicators allow for the determination of whether and the extent to which there are true differences in results among studies included in a meta-analysis (

41). When the p value associated with the Q statistic was significant, and there was at least moderate variability in effect size estimates (that is, when I

2 was at least .50) (

41), meta-regressions were performed with individual moderators. All analyses were performed with the metafor package for R (

42).

Given that we collected and synthesized data from previous research in which informed consent was already obtained by the study investigators, this research was exempt from ethics committee approval, and separate informed consent was not needed.

Results

Systematic Review Results

Overall, 28 records (

18,

19,

43–

68) of 23 separate studies were included in this review: 10 (43%) were RCTs, three (13%) were quasi-experimental studies, and 10 (43%) were naturalistic studies. [Sample, study, and intervention characteristics are summarized in the

online supplement.]

Sample characteristics.

Most participants were middle age (the mean±SD was 43.17±4.76 years, N=20 studies), male (58.00%±21.00%, range 26%−95%, N=23), and white (68.00%±20.39%, range 34%−100%, N=18). When reported (N=21), most participants were recruited from outpatient settings (N=17; 81%).

Study characteristics.

For the RCTs, three studies had sample sizes less than 100 (33, 47, and 82 participants each); the remaining seven studies had sample sizes ranging from 101 to 519 participants (292.86±154.87). The quasi-experimental studies had sample sizes ranging from 68 to 296 participants. The naturalistic studies were generally smaller: nearly half had sample sizes of 30 or fewer participants, although the remaining studies had sample sizes ranging from 61 to 174 participants. Most studies were carried out in the United States (N=15); others were based in Canada (N=3), Australia (N=2), the United Kingdom (N=2), Denmark (N=1), and the Netherlands (N=1). Of those studies that included a follow-up assessment point (N=15), the average length of time between postintervention and first follow-up was 25 weeks (range 9–52). Three of these studies included a second follow-up assessment conducted 17–26 weeks later.

Intervention characteristics.

Of the intervention studies, nine studies (41%) examined relatively brief interventions that met weekly for eight to 16 weeks, seven studies (32%) included more extended interventions that met daily or weekly for between 29 and 83 weeks, and one study included an intervention that met every other week for 26 weeks. Seventeen studies provided information on study interventionists: Interventions were led by a mental health professional in six studies (35%), by a peer specialist in six studies (35%), and by both a professional and a peer in five studies (29%). When reported (N=7), the mean number of sessions of experimental treatment attended across studies was 6.49±3.39. Interventions were delivered in individual (N=6), group (N=12), or a combination of both formats (N=4). All were manualized or included some sort of standardized curriculum. Most studies included interventions that focused on a combination of recovery, hope, and empowerment outcomes (N=14; 64%); fewer studies (N=8; 36%) were focused on only one of these outcomes.

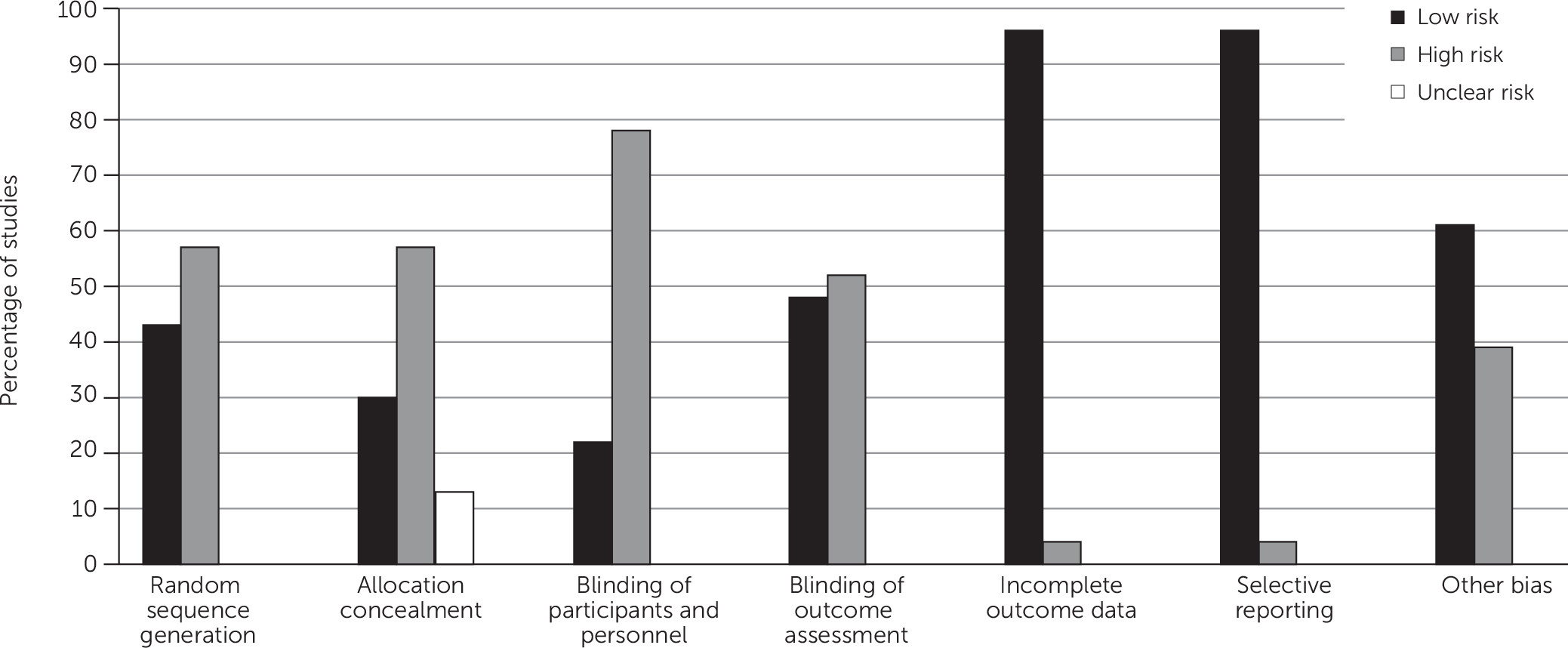

Risk of Bias and Study Quality

Figure 1 presents consensus risk of bias ratings obtained from the two independent reviewers. As shown, the highest percentage of high-risk ratings pertained to the “blinding of participants and personnel” item; most studies were single blind because it was not possible to blind participants to their group assignment due to the psychosocial nature of the interventions. However, slightly more than 50% of the studies demonstrated low risk regarding the “blinding of outcome assessment” item, either because they used procedures that blinded assessors to participants’ conditions or did not use interviewer-rated assessments. More than half of the studies demonstrated high risk of selection bias because of lack of randomization to condition or lack of allocation concealment. “Other bias” was noted in a smaller percentage of the studies for reasons that included use of a waitlist control instead of active comparison group, methodological discrepancies between conditions or time points, use of assessors who were also intervention providers, and lack of a true baseline. The smallest percentages of high-risk ratings were observed for the “incomplete outcome data” and “selective reporting” items because most studies contained a relatively small percentage of missing data and did not demonstrate evidence of failure to report certain outcomes.

Of those studies that included a comparison group (N=13), a majority (N=7; 54%) were active treatments, fewer (N=5; 38%) were waitlist control conditions, and one study was characterized by assessment and monitoring.

Meta-Analysis Results

Of the 10 RCTs, three were not included in the meta-analysis. Two of these studies (

18,

44) were excluded because they presented data averaged across study groups; the third (

58) reported results for only the experimental group. The remaining seven studies provided group-based results and were included in the meta-analysis. Five of these studies provided data at both postintervention and follow-up.

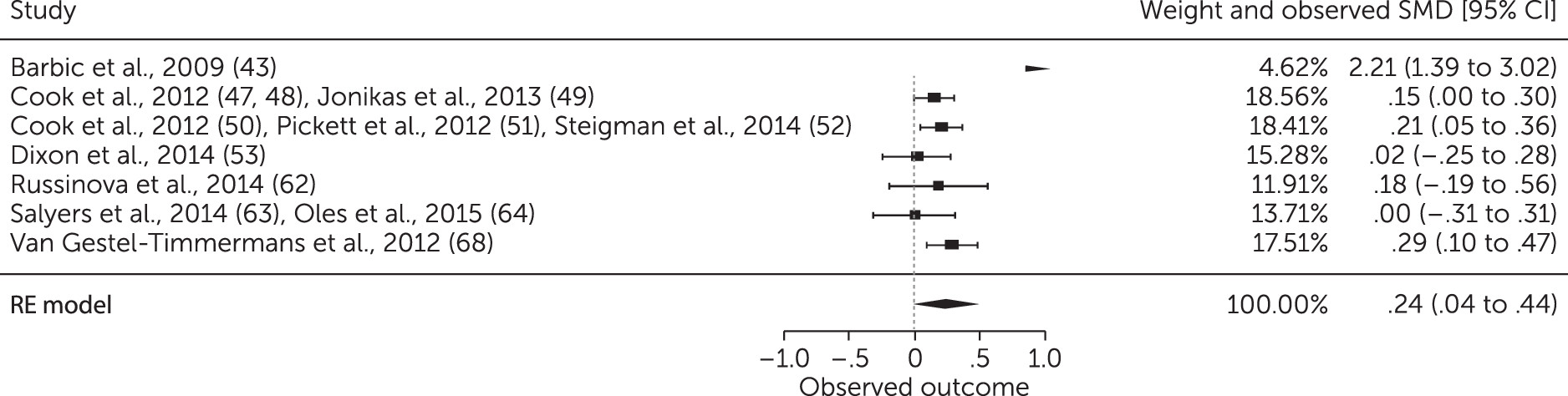

Postintervention effect sizes.

Figure 2 is a forest plot of the aggregate effect sizes for person-oriented recovery, empowerment, and hope outcomes at the postintervention assessment point. The average standardized mean change effect size was .24 (95% confidence interval [CI]=.04–.44), indicating that those in the recovery-oriented intervention group improved to a greater, albeit modest, extent than those in the comparison group. Heterogeneity in effect sizes was sufficient to justify performance of meta-regressions (Q=28.00, df=6, p<.001; I

2=78.57%).

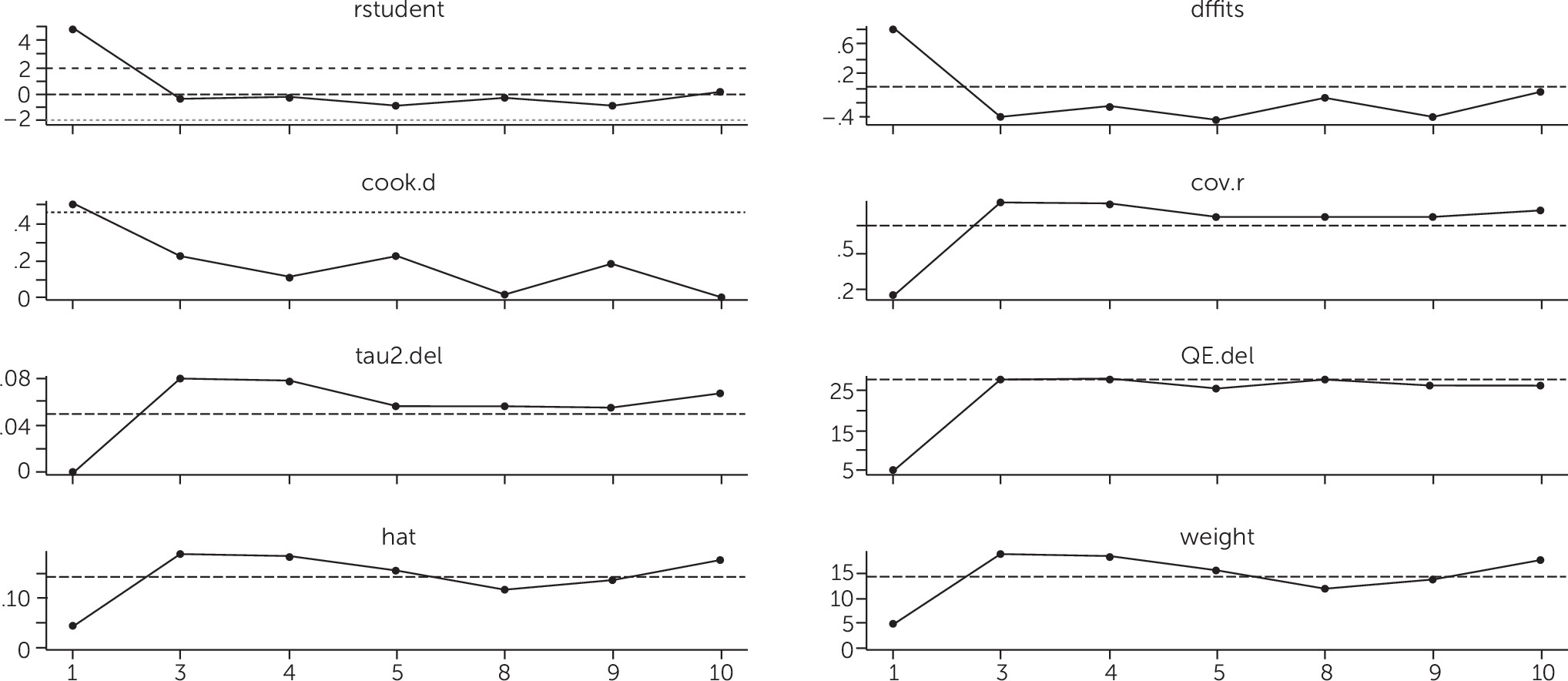

Sensitivity analyses.

Figure 3 presents results from sensitivity analyses. One study (

43) was identified as an outlier; however, even when this study was removed, there was little difference in the overall effect size (effect size=.17, CI=.09–.25), and the effect size remained significant (p<.001). Therefore, this study was included in subsequent analyses.

Follow-up effect sizes.

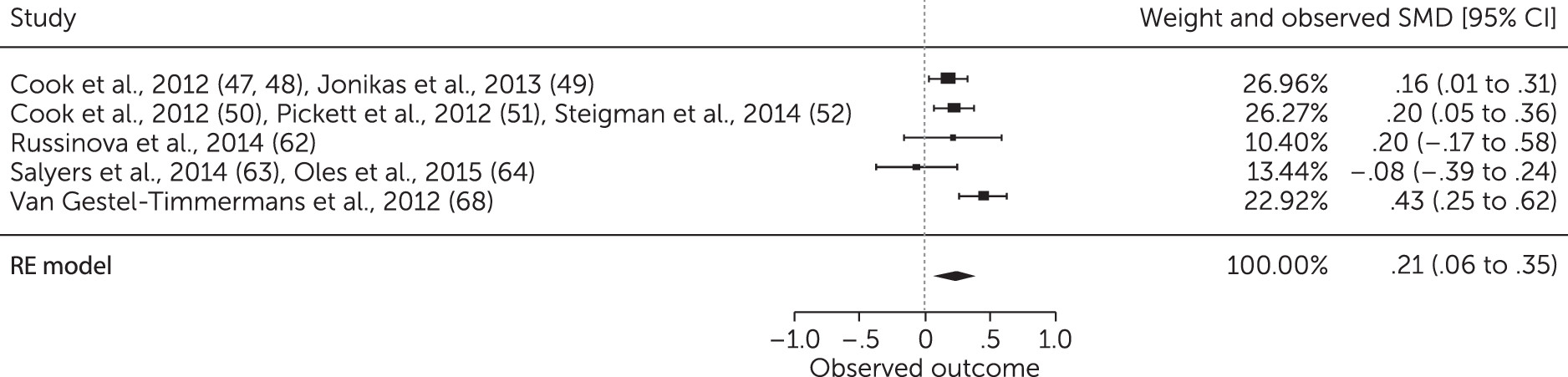

All studies included in the meta-analysis had only one follow-up assessment point.

Figure 4 presents a forest plot of the aggregate effect sizes for person-oriented recovery, empowerment, and hope outcomes at follow-up. As shown, those in the intervention group continued to have higher person-oriented recovery outcomes at follow-up when compared with the control group (overall effect size=.21, CI=.06–.35). Heterogeneity in effect sizes was not sufficient for meta-regression analyses (Q=9.11, df=4, p=.06; I

2=56.09%).

Moderator analyses.

Table 1 presents results from moderator analyses pertaining to the postintervention effect sizes. A study (

43) of an intervention that was provided by both mental health professionals and peers demonstrated the greatest difference in recovery outcomes between the intervention and control groups when compared with studies of interventions provided by mental health professionals or peers alone. There were no other significant effects of individual, intervention, or methodological characteristics.

Discussion

Although several reviews of functional recovery among people with serious mental illnesses exist (

2–

4) and there have been summary reports on person-oriented recovery definitions (

69), measures (

70), and specific services (

71), to our knowledge this is the first comprehensive synthesis of findings from longitudinal research on person-oriented recovery in this population. The systematic review identified 23 studies that assessed person-oriented recovery constructs quantitatively over at least two time points. Most of these studies were either RCTs or naturalistic studies that were relatively small and short and that comprised homogeneous samples that were recruited from outpatient settings. Varieties of person-oriented recovery, empowerment, and hope assessments were used, and several recovery-oriented interventions were evaluated. Most studies demonstrated high risk of bias in at least one area; however, this is true for many studies of nonpharmacological interventions (

33).

Findings from the meta-analysis, comprising 1,739 participants in seven independent studies, suggest that mental health care consumers indeed experience greater improvement in person-oriented recovery outcomes when they are involved in recovery-oriented mental health treatment versus usual care or other types of treatment (such as participating in a problem-solving group or receiving information and resources). These gains appear to be sustained, at least in the short term. Additional studies included in the review largely corroborate results from the meta-analysis because significant improvements in at least one person-oriented recovery construct were noted in 11 of 16 of these studies. The present review and meta-analysis expand on findings from individual studies (

24–

26) that suggest a positive effect of psychiatric rehabilitation and other recovery-oriented mental health services on consumers’ level of perceived recovery, empowerment, and hope.

Moderator analyses yielded several interesting and informative results. First, no individual characteristics moderated differences in person-oriented recovery outcomes between groups. These findings imply that individuals can experience gains in perceived recovery, empowerment, and hope regardless of their age, gender, or race, supporting a central tenet of the consumer-survivor movement that recovery is possible for everyone (

72). Recruitment setting was also not a significant moderator, although, notably, studies included in the meta-analysis recruited participants primarily from outpatient settings, with only one study recruiting participants from both inpatient and outpatient facilities. The disproportionately few number of studies conducted in inpatient settings in this review is consistent with a general lack of recovery-oriented practices within psychiatric hospitals (

73). Additional research is needed to clarify the impact of recruitment setting on person-oriented recovery.

Second, intervention duration and dosage were not significant moderators. Because most of the studies included relatively brief interventions and because the average number of sessions attended was small, these results suggest that it may be possible to promote person-oriented recovery in a short period of time. In addition, intervention mode did not moderate differences in person-oriented recovery between groups. However, only one study included in the meta-analysis used an individual format, and further research is warranted to establish the optimal mode of delivery for recovery-oriented interventions. Type of intervention provider moderated differences in person-oriented recovery outcomes between groups; a study of an intervention that was delivered by both mental health professionals and peer providers (

43) demonstrated the greatest differences between groups. The strength of this conclusion is limited given that only one study included in the meta-analysis used such an intervention; however, we performed an exploratory meta-analysis that included RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, which added another study of this kind and produced similar results. Thus, it is possible that the collaborative efforts of mental health professionals and peer providers may lead to the greatest gains in person-oriented recovery.

Third, type of comparison group (waitlist control versus active treatment) did not moderate differences in person-oriented recovery outcomes between groups. Active treatment conditions included assertive community treatment, provision of resources and information, and a problem-solving group. Our findings suggest that without an explicit focus on recovery-oriented principles (such as personal goals, needs, and strengths; collaborative working relationship), mental health services are unlikely to affect person-oriented recovery.

Several limitations to our research merit discussion. First, only a few studies were included in the meta-analysis. Because there were fewer than 10, we were unable to formally assess for publication bias (

74). However, we attempted to reduce bias by asking study authors to provide any other studies (published or unpublished) that would meet criteria for the review, and we included these accordingly.

Second, each study included in the meta-analysis evaluated a different recovery-oriented intervention; thus, no conclusions may be drawn about whether certain interventions are associated with greater gains in person-oriented recovery, empowerment, and hope. This is an area for future research.

Third, data about the recovery orientation of each intervention were not systematically available across studies, and we did not use a measure of recovery-orientation to evaluate these interventions when selecting studies for the meta-analysis. The availability of such data would have strengthened the methodological rigor of the selection process.

Fourth, variables selected for moderator analyses were limited by the availability of data across studies. Therefore, we were unable to examine effects of other potentially important factors that might facilitate or limit person-oriented recovery, such as psychiatric symptoms (

17–

19) or community participation (

21,

22).

Finally, aggregation across multiple constructs may be viewed as a limitation. However, because recovery, hope, and empowerment are conceptually (

16) and empirically related constructs (

75,

76) and because we used established meta-analytic procedures that accounted for dependency in the outcomes, we felt that aggregation was justified.

Conclusions and Implications for Research and Practice

These findings have several implications for research and practice. High-quality research on person-oriented recovery is needed, including more tightly controlled and larger studies with more heterogeneous samples that examine changes over time in person-oriented recovery constructs. An important step would be the determination of consensus measures of person-oriented recovery constructs that could be used in this research. In addition, multiple studies of the same intervention, along with studies that compare recovery-oriented treatment with other treatments rather than usual care, are needed.

Although these needs exist, our findings suggest several implications for practice. The interventions included in the studies reviewed here have certain characteristics, including emphasizing psychoeducation, developing self-management skills, and fostering self-determination. Our results suggest that interventions such as these can promote increased recovery, hope, and empowerment among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Such findings support more widespread implementation of these types of interventions as a standard component of mental health and psychiatric rehabilitation services. All the interventions examined here were structured and manualized, with specified components and activities that allowed for participants to share experiences and receive support while also learning and practicing skills or strategies for succeeding at managing their illness and for helping them identify and take steps toward reaching their personal goals and achieve greater community integration. Thus, resources for providing recovery-oriented services with some evidence base are available and can be implemented within programs that serve consumers with serious mental illnesses.

In addition, greater collaboration between mental health professionals and peers might enhance person-oriented recovery. There is evidence that a partnership between peer- and professionally-delivered services may be an effective model of service delivery for persons with psychosis (

77–

79) and may be especially well suited to interventions that aim to enhance person-oriented recovery. Mental health professionals can provide information about recovery constructs and their relationship to attaining goals, guide discussion on applying success in one area of life to progress on other goals in other areas, and assist consumers in trying out newly learned skills or strategies in real-world situations. They can work alongside peer specialists who provide support, model self-efficacy and agency in real-world situations and coping when problems arise, and reinforce attempts to use new skills outside of the treatment setting. It could be that this partnering of expertise can have the most impact in enhancing recovery for consumers with serious mental illnesses.