Serious mental illnesses affect approximately 4% of the population (

1). Functional impairments related to serious mental illness interfere with life activities, such as work, independent living, and self-care (

2). Individuals with serious mental illness typically experience periods of illness exacerbation characterized by greater impairment interspersed with periods of partial or complete remission (

3,

4). With appropriate supports, people with serious mental illness can lead rewarding and productive lives, even in the context of ongoing symptoms (

5,

6).

Self-management interventions that increase and lengthen the periods in which people with serious mental illness remain healthier are popular and increasingly offered at clinics (

7–

12). Self-management interventions can help people adhere to treatment regimens, reduce the severity and distress associated with symptoms, avoid hospitalization, increase self-esteem, and improve perceived recovery (

13). However, the barriers associated with clinic-based care may limit the benefits of these interventions. When individuals experience symptom exacerbations (arguably, when they need illness management support the most), they may avoid going to a clinic or interacting with others, perhaps because of the clinic’s distance from their residence or hours of operation (

14,

15), the stigma associated with seeking care (

16), or dissatisfaction with services (

17–

19).

Mobile health (mHealth) approaches that use mobile phones in support of health care can help overcome some of the barriers associated with clinic-based care. Mobile phones are ubiquitous, even among people with serious mental illness, who often have limited access to resources (

20–

22). Research across continents has shown that the majority of adults with serious mental illness are interested in using their mobile phones as instruments for self-management (

23). Early mHealth efforts have produced promising outcomes in terms of feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy in this population (

24–

29). Whether mHealth interventions can serve as stand-alone treatments, effectively engage individuals with serious mental illness in remote care, and produce clinical outcomes that are comparable to those of clinic-based interventions is unknown. As more mHealth and clinic-based interventions are made accessible in real-world practice, patients and their providers will have more options to choose from when deciding on their preferred model of care. Direct comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of existing interventions for a designated clinical problem is at the core of comparative effectiveness research.

Our objective was to compare smartphone-delivered mHealth to a clinic-based, group self-management intervention for people with serious mental illness. We evaluated differences between treatment groups in patient engagement, satisfaction, and clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, this article reports on the first comparative effectiveness trial with a head-to-head comparison of mHealth and a clinic-based intervention for people with serious mental illness.

Methods

We conducted an assessor-blind, two-arm, randomized controlled trial between June 2015 and September 2017 in partnership with Thresholds, a large agency that provides services to people with serious mental illness living in the midwestern United Sates. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and Dartmouth College and monitored by an independent safety monitoring board at Dartmouth’s Department of Psychiatry. All study participants completed informed consent. Individuals were randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) into one of two treatment arms: an mHealth intervention (FOCUS) or a clinic-based group intervention (Wellness Recovery Action Plan [WRAP]). Interventions were deployed for a period of 12 weeks, using cycles of eight cohorts of participants assigned to individual FOCUS or group-based WRAP over parallel periods. We conducted assessments at baseline (zero months), posttrial (three months), and follow-up (six months). Participants were not monetarily incentivized to engage in interventions but were compensated for completing assessments ($30 per assessment). [A CONSORT diagram of the study is available in an online supplement to this article.]

Participants

Participants were identified by using the electronic health record and then recruited by 20 clinical teams at three centers. Clinical staff approached candidates to describe the project and provide informational handouts with a contact number for the research team. Interested clients called study staff to learn more and undergo a brief phone screening. Suitable candidates were invited to attend a more comprehensive in-person evaluation meeting. Inclusion criteria were chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder; age ≥18 years; and a rating ≤3 on one of three items constituting the domination by symptoms factor from the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (

30,

31), indicating a need for the type of resources both interventions may offer. Exclusion criteria were hearing, vision, or motor impairment affecting operation of a smartphone (determined by using a demonstration device); less than fifth-grade English reading ability (determined with the reading section of the WRAT-4 [

32]); and exposure to WRAP or FOCUS in the past three years.

Randomization and Blinding

The study statistician created a computer-generated randomization list. Individual intervention allocations were placed in sequentially numbered envelopes containing instructions to contact an mHealth support specialist (for FOCUS) or a group facilitator (for WRAP) to schedule an appointment. Study assessors were excluded from study meetings in which procedures that would jeopardize blinding were discussed. Participants were instructed not to disclose their treatment allocation during assessments.

Interventions

FOCUS (

25,

33,

34) is a multimodal, smartphone-delivered intervention for people with serious mental illness that includes three components: FOCUS application (app), clinician dashboard, and mHealth support specialist. The system includes preprogrammed daily self-assessment prompts and on-demand functions that can be accessed 24 hours a day. Self-management content targets five broad domains: voices (coping with auditory hallucinations via cognitive restructuring, distraction, and guided hypothesis testing), mood (managing depression and anxiety via behavioral activation, relaxation techniques, and supportive content), sleep (sleep hygiene, relaxation, and health and wellness psychoeducation), social functioning (cognitive restructuring of persecutory ideation, anger management, activity scheduling, and skills training), and medication (behavioral tailoring, reminders, and psychoeducation). Content can be accessed as either brief video or audio clips or sequences of digital screens with written material coupled with images (

34). FOCUS users’ responses to daily self-assessments are displayed on a digital dashboard. Participants received brief weekly calls from an mHealth support specialist who assisted them in all technical and clinical aspects of the intervention (

35). [A complete description of the interventions is available in the

online supplement.]

WRAP (

12) is a widely used (

36) group self-management intervention led by trained facilitators with lived experience of mental illness. Sessions follow a sequenced curriculum, and specific group discussion topics and examples draw from the personal experiences of the participants and cofacilitators. The model emphasizes individuals’ equipping themselves with “personal wellness tools,” each focusing on recovery concepts (for example, hope, personal responsibility, and self-advocacy), language (for example, person-first recovery language), development of a WRAP (for example, establishing a daily maintenance plan and identifying and responding to triggers and early warning signs), and encouraging positive thinking (for example, changing negative thoughts to positive thoughts, building self-esteem, suicide prevention, and journaling). Facilitators incorporate these tools into a written plan, which includes daily maintenance, identification of triggers and methods to avoid them, identification of warning signs and response options, and a crisis management plan.

FOCUS and WRAP are similar in that both are recovery oriented, use an array of empowerment and self-management techniques, and involve similar intervention periods; empirical findings suggest that both interventions are engaging and beneficial to people with serious mental illness (

25,

34,

37–

40). The differences between these approaches represent core distinctions between mHealth and clinic-based models of care (that is, accessed in one’s own environment versus administered in a center, largely automated versus person delivered, and on demand versus scheduled).

Measures

Engagement.

We considered participants as commencing treatment if they used FOCUS once or attended one WRAP session. We calculated engagement in treatment for each participant weekly by using his or her FOCUS use data (logged by the software) or WRAP session attendance (logged by WRAP facilitators). Participants in the FOCUS arm were considered engaged if they used the app on at least five of seven days a week (that is, approximately 70%). A FOCUS “use” event is recorded as such only if, following a prompt, participants elect to engage in a clinical status assessment or if they self-initiate one of the FOCUS on-demand tools. Participants in the WRAP arm were considered engaged if they attended at least 60 minutes of the scheduled 90-minute group session (that is, approximately 70%) or completed a makeup session in the same week.

Satisfaction.

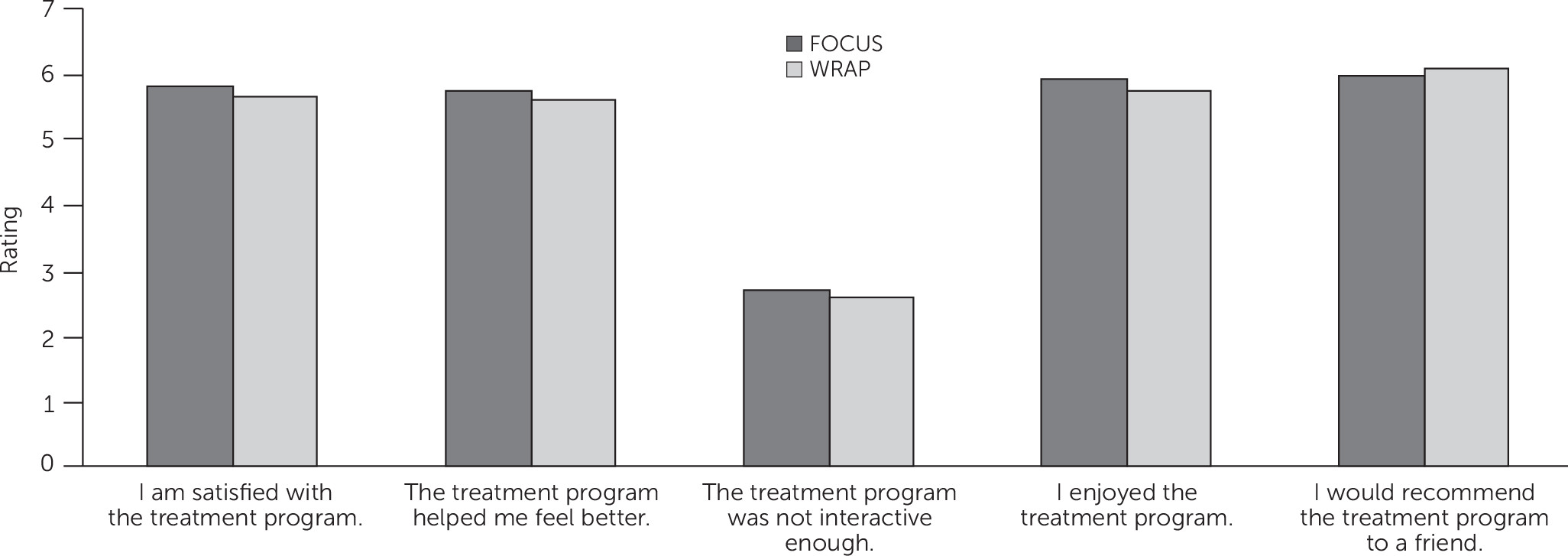

We measured satisfaction as the sum of five self-report items completed during the three-month, postintervention assessment. Participants rated the following statements with a 7-point rating scale (1, strongly disagree, to 7, strongly agree): I am satisfied with the treatment program, the treatment program helped me feel better, the treatment program was not interactive enough (reverse scored), I enjoyed the treatment program, and I would recommend the treatment program to a friend.

Clinical outcomes.

Our primary clinical outcome was general psychopathology, which is most appropriate for the different clinical groups represented in the sample of people with serious mental illness. General psychopathology was measured with the Symptom Checklist–9 (SCL-9) (

41), a brief version of the Symptom Checklist–90R (

42) that captures several domains of mental health (for example, anxiety, somatization, hostility, paranoid thinking, and psychoticism) and provides a single global rating of severity (

43,

44). Secondary clinical outcomes included depression, psychosis, recovery, and quality of life. Depression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition (BDI-II) (

45), which includes 21 items rated on a 4-point scale, summed for a total depression severity score. Psychosis was assessed with the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS) (

46). PSYRATS includes dimensions of auditory hallucinations (for example, frequency, duration, loudness, and distress) and delusions (for example, preoccupation, conviction, and disruption). Recovery was assessed with the RAS (

30,

31), a 24-item measure assessing five recovery factors with a 5-point Likert scale: personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, goal and success orientation, reliance on others, and domination by symptoms. Quality of life was assessed as the total of six items focusing on one’s personal evaluation of one’s life, self, family, time spent with family, time spent with others, and participation in activities. Participants respond on a 7-point delighted-terrible scale. Clinical outcome measures were administered by assessors who were trained and supervised by licensed clinical psychologists with extensive experience in their administration among individuals with serious mental illness. Challenges in administration or scoring were discussed and resolved during weekly project team meetings.

Sample Size

We designed the study to detect a medium effect (defined as f=.24) in difference between groups in change in clinical outcome from baseline to three months, with 80% power (α=.05). This power is achieved with 72 participants per group. To allow for 10% attrition, 80 participants were randomly assigned to each group.

Analytic Approach

We used an intent-to-treat analysis that included all randomly assigned individuals. For treatment comparisons among clinical outcomes, we used mixed-effects models, including treatment condition, time of assessment, and an interaction term for treatment condition × time. Linear mixed models (

47) were fit for all outcomes except PSYRATS, which was modeled via nonlinear Poisson hurdle mixed model, which estimates a logistic model for probability of a count >0 (likelihood of experiencing symptoms) as well as a Poisson model for mean symptom ratings if any symptoms were experienced (

48). PSYRATS was modeled in this way because of the skewed nature and zero-inflation observed for this outcome (for example, 64% of individuals had a score of 0 at baseline), which made linear models inappropriate for this outcome. We evaluated engagement by using chi-square tests, and treatment satisfaction was assessed with t tests. [The

online supplement includes a complete description of the analyses.]

Results

The study enrolled 163 participants, whose mean age was 49. Most participants were male (N=96, 59%) and African American (N=106, 65%). Diagnoses were as follows: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 49% (N=80); bipolar disorder, 28% (N=46); and major depressive disorder, 23% (N=37). Participants differed between treatment groups only in that significantly more participants randomly assigned to FOCUS had previously used a smartphone (73% versus 57%, χ

2=4.81, df=1, p=.03).

Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics by group.

Engagement

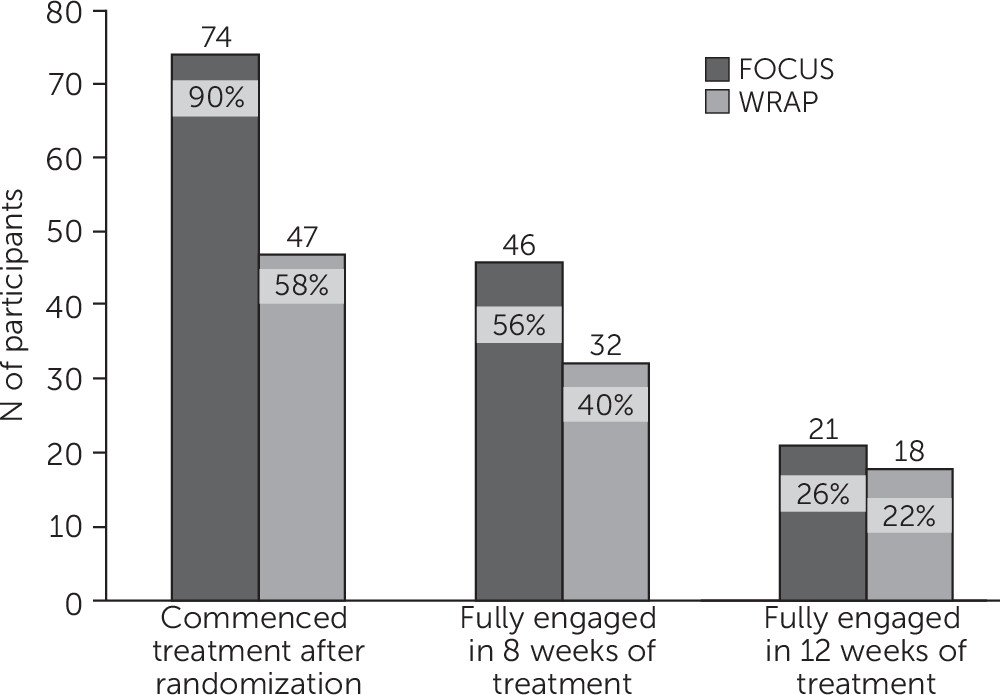

Following randomization, 90% (N=74) of participants assigned to FOCUS commenced use of the mHealth app, and 58% (N=47) of those assigned to WRAP attended at least one group session (χ

2=22.11, df=1, p<.001) (

Figure 1). Averaging across all participants assigned to FOCUS, participants used the app on 5.4±2.4 days in the first week of the intervention, on 4.6±2.7 days in the third week, on 4.3±2.7 days in the sixth week, on 3.9±2.7 days in the ninth week, and on 3.8±2.9 days in the last week. In the first week of WRAP, 48% (N=39) of assigned participants attended the weekly meeting; 42% (N=34) attended in the third and sixth weeks, 36% (N=29) attended in the ninth week, and 28% (N=23) attended in the last week. FOCUS group participants were more likely than WRAP participants to fully engage in treatment for at least eight weeks (56% versus 40%) (χ

2=4.50, df=1, p=.03) (

Figure 1). The groups did not differ in the proportions of participants fully engaging in all weeks of treatment.

Satisfaction

Mean posttreatment satisfaction ratings were similar between groups: overall ratings of 25.7±3.8 for FOCUS and 25.5±3.6 for WRAP (t=–.31, df=1, p=.76).

Figure 2 shows average responses for the individual satisfaction items. No adverse events were reported for participants in either intervention arm.

Clinical Outcomes

Treatment groups did not differ in change from baseline to three months postintervention on primary and secondary clinical outcomes. Primary analyses found no significant differences in clinical outcomes between diagnostic groups. Exploratory analyses found within-group changes.

Table 2 summarizes the mean scores for clinical outcomes. Improvement between baseline and three months (end of treatment) in the primary clinical outcome, general psychopathology as measured by the SCL-9, was seen for FOCUS (mean±SE of the estimated mean difference=−2.73±.75, t=−3.64, df=289, p<.001) and WRAP (−2.14±.76, t=−2.84, df=289, p=.005). Similar improvements in SCL-9 scores were seen between baseline and six months for FOCUS (−2.51±.75, t=−3.33, df=289, p=.001) and for WRAP (−1.93±.77, t=−2.51, df=289, p=.01). Improvement between baseline and three months in BDI-II scores was seen for FOCUS (−2.76±1.09, t=−2.54, df=289, p=.01) and WRAP (−2.33±1.10, t=−2.13, df=289, p=.03). Similar improvements in BDI-II were seen between baseline and six months for FOCUS (−4.21±1.09, t=−3.85, df=289, p<.001) and for WRAP (−3.74±1.12, t=−3.34, df=289, p<.001). Improvements between baseline and three months in RAS scores were seen for WRAP (2.44±1.10, t=2.21, df=288, p=.03). Between baseline and six months, improvements in RAS scores were seen for FOCUS (4.56±1.10, t=4.16, df=289, p<.001) and for WRAP (2.86±1.12, t=2.55, df=289, p=.01). No significant within-group differences in PSYRATS or quality-of-life scores were noted between baseline and three months. Between baseline and six months, significant improvements were seen in quality of life among the FOCUS participants (1.58±.62, t=2.55, df=289, p=.01).

Treatment groups did not differ on changes from three months postintervention to the six-month follow-up. Within treatment group, improvement in RAS scores was seen for FOCUS (2.74±1.11, t=2.46, df=288, p=.01) (

Table 2).

FOCUS Effects

In the FOCUS group, education and treatment engagement were significantly associated with secondary clinical outcomes. Having more than a high school education was associated with larger increases in RAS scores (mean±SE of the estimated mean difference from baseline to three months=4.31±2.15, t=1.71, df=145, p=.05), as was more weeks of engagement (five or more days per week of FOCUS use) (.57±.28, t=2.07, df=133, p=.04). Age, gender, race, past use of a smartphone, and number of hospitalizations were not associated with mHealth intervention outcomes.

Discussion

The FOCUS mHealth intervention produced clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction ratings that were comparable to those of WRAP, an evidence-based, self-management intervention. No adverse events were reported for participants in either intervention arm. FOCUS had significantly higher treatment commencement rates after random assignment (90%), compared with WRAP (58%). These findings suggest that FOCUS was easier to initiate or more accessible. Significantly more FOCUS participants fully completed eight or more weeks of treatment (56%), compared with WRAP (40%). Groups did not differ significantly in the percentage of participants who fully completed 12 weeks of treatment. Taken together, participants were exposed to treatment content more often and over longer intervention periods (dose) via FOCUS than via clinic-based WRAP.

Satisfaction with treatment did not differ across groups. Participants provided high satisfaction ratings for FOCUS and WRAP, and participants in each approach reported that it was enjoyable and interactive and helped them feel better. We draw several conclusions. First, people with serious mental illness can be satisfied with mHealth treatments that are largely automated, involving weekly remote check-in calls but minimal in-person contact. Second, although barriers related to clinic-based care might have affected treatment commencement and engagement in WRAP, such barriers did not negatively affect participants’ overall impressions of the intervention. Participants in each arm were not exposed to the other treatment, and thus their satisfaction ratings were not grounded in familiarity with an alternative. A cross-over design in which participants experienced both interventions would enable more direct comparison of satisfaction.

Changes in primary (general psychopathology) and secondary (depression, psychosis, recovery, and quality of life) clinical outcomes did not differ by intervention. No differences were seen between groups in retention of gains three months after the conclusion of the intervention (at six-month follow-up). Exploratory analyses within treatment arms showed significant and comparable reductions in psychopathology and depression in both treatment groups. Significant improvements in recovery were seen in the WRAP group at the end of treatment (three months) and in the FOCUS group at six-month follow-up.

Among FOCUS participants, a higher level of education and greater treatment engagement (that is, weeks of daily smartphone app use) were both linked to greater recovery postintervention. Notably, age, gender, race, having previous experience with smartphones, and number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations (an indicator of baseline illness severity) were not associated with clinical outcomes.

This study had notable strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first randomized controlled trial examining the effects of a smartphone intervention involving individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The comparator intervention (WRAP) is an active evidence-based treatment. Both interventions were introduced at the study site at the same time, ensuring equal levels of enthusiasm among study staff and clinical personnel. Additional methodological strengths included use of psychometrically sound outcomes measures, random assignment, maintenance of assessor blindness throughout the study, and deployment of interventions as parallel cohorts to control for historical effects. Both interventions were delivered with guidance from treatment experts; the mHealth support specialist was trained and supervised via phone by the lead FOCUS developer (DBZ). WRAP facilitators were trained by the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery (the premiere WRAP training and education center) and supervised on site by a certified advanced-level WRAP facilitator.

The study had several limitations. We did not include a treatment-as-usual comparator arm. We thus cannot conclude that the clinical outcomes reported in the study are a direct result of the interventions deployed rather than of the passage of time or of artifacts related to involvement in research. FOCUS participants received a smartphone with an active data plan, which may be less likely in standard care. However, once they were randomly assigned to the mHealth arm, participants’ access to the device and data were not contingent upon their use of the intervention app. This noncontingent access suggests that ongoing engagement in FOCUS was not for secondary gains. In addition to receiving new interventions in the context of research, participants continued to receive various services from the community agency, which may have influenced the results. The measures of engagement and satisfaction were developed for this study and have not been validated in previous research. Because the study was powered to detect differences in the full sample between treatment groups, exploratory analyses had reduced power, and thus the results should be interpreted cautiously.

The findings support the notion that mHealth can play an important role in 21st century mental health care (

49,

50). Contemporary mobile phone “smart” functionalities enable these devices to serve as much more than static information repositories (

51). Audio and video media players, graphic displays, interactive capabilities, bidirectional calling and texting, and Internet connectivity create new opportunities to engage patients with both automated resources and human supports. The portability of smartphones enables patients to take them wherever they go. FOCUS users in this study could read, hear, or view self-management skills, suggestions, and demonstrations that were relevant to the challenges they encountered as they went about their daily life. Instead of having to retain and recall clinicians’ suggestions, they accessed their “pocket therapist” on demand—an experience akin to a friend checking in on them (

34). FOCUS users’ daily self-assessments were relayed to their mHealth support specialist, who reviewed the data to better understand what they were experiencing. This information was brought up in their weekly check-in calls, which likely strengthened the feeling that a caring individual was paying attention to their status (

35). The combination of automated functions and live remote human support facilitated a therapeutic model unlike any they had encountered. For some, this proved to be engaging and helpful.

Conclusions

The FOCUS model is one of several promising mHealth approaches. Additional paradigms include using mHealth applications to augment clinic-based services to improve their efficacy (

52,

53) and leveraging multimodal smartphone embedded sensors (for example, GPS, accelerometers, and microphone) to unobtrusively collect information about patients’ behavior, context, and functioning (

54,

55). These mobile data can be shared with clinicians to enhance their patient-monitoring capabilities and inform more tailored in-person care (

56,

57).

Evidence from mHealth research will accumulate over the upcoming years, including additional promising results from randomized controlled trials. As more mHealth interventions prove to be engaging and clinically useful to patients with serious mental illness, enthusiasm for their use in clinical practice will grow (

15). In the future, it will be important to ensure that these mHealth technologies are deployed ethically and responsibly (

58).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of staff and service recipients at Thresholds, Chicago.