There now are more than 200 mental health courts across the country that are designed to reduce arrest and detention of the large numbers of persons with mental illness who have become increasingly involved in the criminal justice system (

1,

2,

3 ). Mental health courts have separate dockets, and participation is voluntary. Once a person enters the program, he or she must agree to follow a treatment regimen, modify his or her behavior, and be monitored by the court in exchange for dismissal of charges or avoidance of incarceration (

4,

5 ).

Although mental health courts vary from one another in some details, there are many commonalities. Most are nonadversarial, using a team approach in which defense attorneys and prosecuting attorneys do not dispute the defendant's innocence or guilt. Rather, they work with judges, criminal justice personnel, boundary spanners (such as social workers and mental health professionals), mental health practitioners, and other providers to find treatment and services, to encourage the defendant to follow court mandates, and to allot sanctions that will address the underlying causes of each defendant's behavior while protecting the public. Team members understand that offenders with mental illness commonly relapse; therefore, they adjust their expectations and give second chances. They collaborate in decisions and enforcement, believing that the team approach is essential to ensure that both criminal justice and mental health needs are met (

4,

5,

6,

7,

8 ).

Only a few studies have examined criminal recidivism as an outcome of mental health court; however, all of them have reported that arrested persons with mental illness diverted into mental health court are no more likely to reoffend than comparable defendants in traditional criminal court and that they are less likely to offend than they were before entering mental health court (

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17 ). Results are mixed on whether completion of mental health court reduces recidivism to a level below that of defendants with mental illness in traditional criminal courts. Most of these studies have followed defendants for only one year or less after mental health court entry, while they were still in mental health court, or for less than one year after exiting the court. Furthermore, most of these studies were conducted within the first few years of the courts' conception, well before the courts became established, when they were still building team relations, hearing procedures, monitoring mechanisms, policies on use of sanctions, and agency collaboration (

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17 ). Only one study, by McNiel and Binder (

14 ), examined criminal recidivism for two years after mental health court exit. They reported that mental health court continued to affect its graduates in this longer period, after the court no longer provided support or monitoring.

Similar to McNiel and Binder (

14 ), we evaluated one mental health court's effectiveness in reducing recidivism two years after defendants exited the program. Unlike their study, which was conducted in the inner city of a major metropolis, ours was based on a court with a jurisdiction that covers two small towns and includes a university and a large rural area. Unlike earlier studies, this study examined an established mental health court; defendants exited the court in its fifth year of operation. We also evaluated court effectiveness in reducing recidivism by comparing defendants who completed the court process—that is, they received their full individualized plans of the court's treatment, services, structure, supervision, and encouragement—with noncompleters (persons ejected from the program or who opted out of it), who received only part of their individualized plans. This distinction is important because becoming a participant in mental health court makes possible but does not ensure that a defendant will obtain all components of the court's program that are the mechanisms by which mental health court is expected to affect recidivism.

Results

Sample description

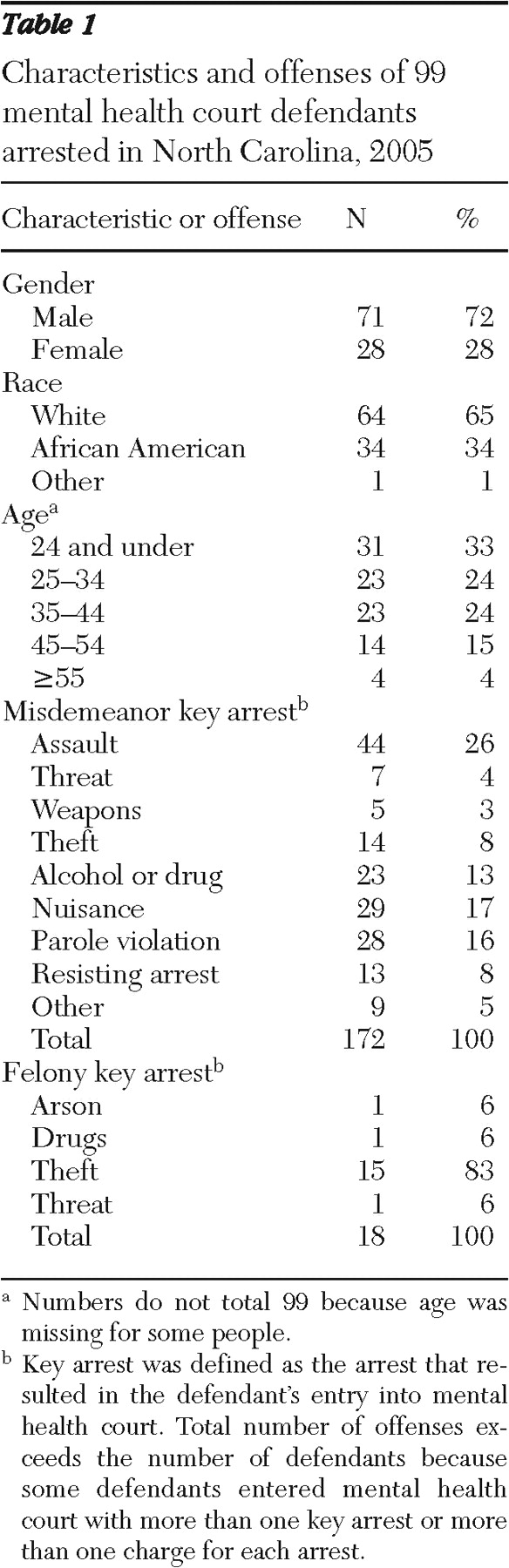

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of our sample. Almost three-fourths were male (72%), almost two-thirds were white (65%), and just over four-fifths were younger than 45 years of age (81%).

In the two years before their key arrest, the cohort had a mean of 4.19±3.86 arrests (range=0–23) (

Table 2 ). Three percent (N=3) had no arrest in the prior two years; 38% (N=38), one or two arrests; and 59% (N=58), three or more arrests. The overwhelming majority (90%, N=89) were charged with only misdemeanors for arrests that brought them into mental health court; 10% (N=10) were charged with felonies as their most serious offenses.

Approximately 90% of key offenses were misdemeanors (

Table 1 ). Misdemeanor assault (mostly simple assault and assault on a female) and nuisance offenses (such as panhandling, indecent exposure, and second-degree trespassing) were most common, at 26% and 17%, respectively. Alcohol and drug offenses and parole violations closely followed in frequency. Felony offenses were overwhelmingly for theft (83%), which included charges such as larceny and possession of stolen goods.

Court completion

After an average of 12.17±6.41 months, most defendants (61%, N=60) completed mental health court by complying with mandates for behavioral changes, following treatment regimens, attending status hearings, and avoiding new criminal offending. In these cases, the court dismissed their charges or, in postadjudication cases, reduced their sentences. The 39% (N=39) who did not complete mental health court returned to traditional criminal court for adjudication of their cases or, in postadjudication cases, to jail or prison. Eight of the noncompleters opted out early in the program after they realized the constraints of court monitoring. The rest (N=31) were ejected after a period of participation (9.18±6.06 months) because of persistent noncompliance with scheduled treatment appointments, court appearances, or both; noncooperation with treatment providers; or prohibited behavior, such as illegal drug use. Rearrest alone did not entail ejection; rearrest was common, with 31% being rearrested at least once while participating in the mental health court program. Although a higher proportion of ejected defendants were rearrested while participating in mental health court (58% of persons ejected versus 20% of completers; p<.001), the court team continued to try to work with them. Indeed, 35% of those ejected had two or more arrests before their exit. The groups differed in age and race, with completers more likely to be white and older. There was no significant difference by gender between persons ejected and completers.

Criminal recidivism

Overall, defendants had a 48% rearrest rate in the two years after exiting mental health court, averaging 1.79±3.07 arrests each (

Table 2 ). The proportion arrested was significantly less than in the two years before entry (48% versus 97%; p<.001), as was the average number of arrests (1.79±3.07 versus 4.19±3.86; p<.001). These pre-post analyses, however, conceal the strong effect that mental health court had when defendants completed the full program, that is, received their individualized treatment and services with support and supervision and were consistent with and continuous in their compliance for six months.

Table 2 shows the proportion of the sample with rearrests and the mean number of arrests in the two years before court entry and after exit from mental health court by exit status. It shows that compared with merely participating in mental health court, completing the program was associated with a greater reduction in recidivism. Completers were significantly less likely than those ejected to be rearrested in the follow-up period. Indeed, most completers were not rearrested in the follow-up period (72%). In contrast, most of those ejected from the mental health court program (81%) were rearrested. The results for those who opted out of the program fell between those of the other two groups, with 63% rearrested during follow-up.

All three court exit groups had fewer arrests after exit than they did before court entry, with both completer and ejected groups showing significant declines. (The decline in arrests among the small number of persons who opted out was nonsignificant.) Those ejected from the program had a significantly larger average number of arrests than completers had both before mental health court and after exiting from it. But among those rearrested, completers did not differ much from noncompleters. Both completers and noncompleters had a mode number of rearrests of one, yet most in either group who were rearrested had two or more arrests, and approximately one-third of both groups fell back into the pattern of cycling in and out of the criminal justice system, with four or more arrests.

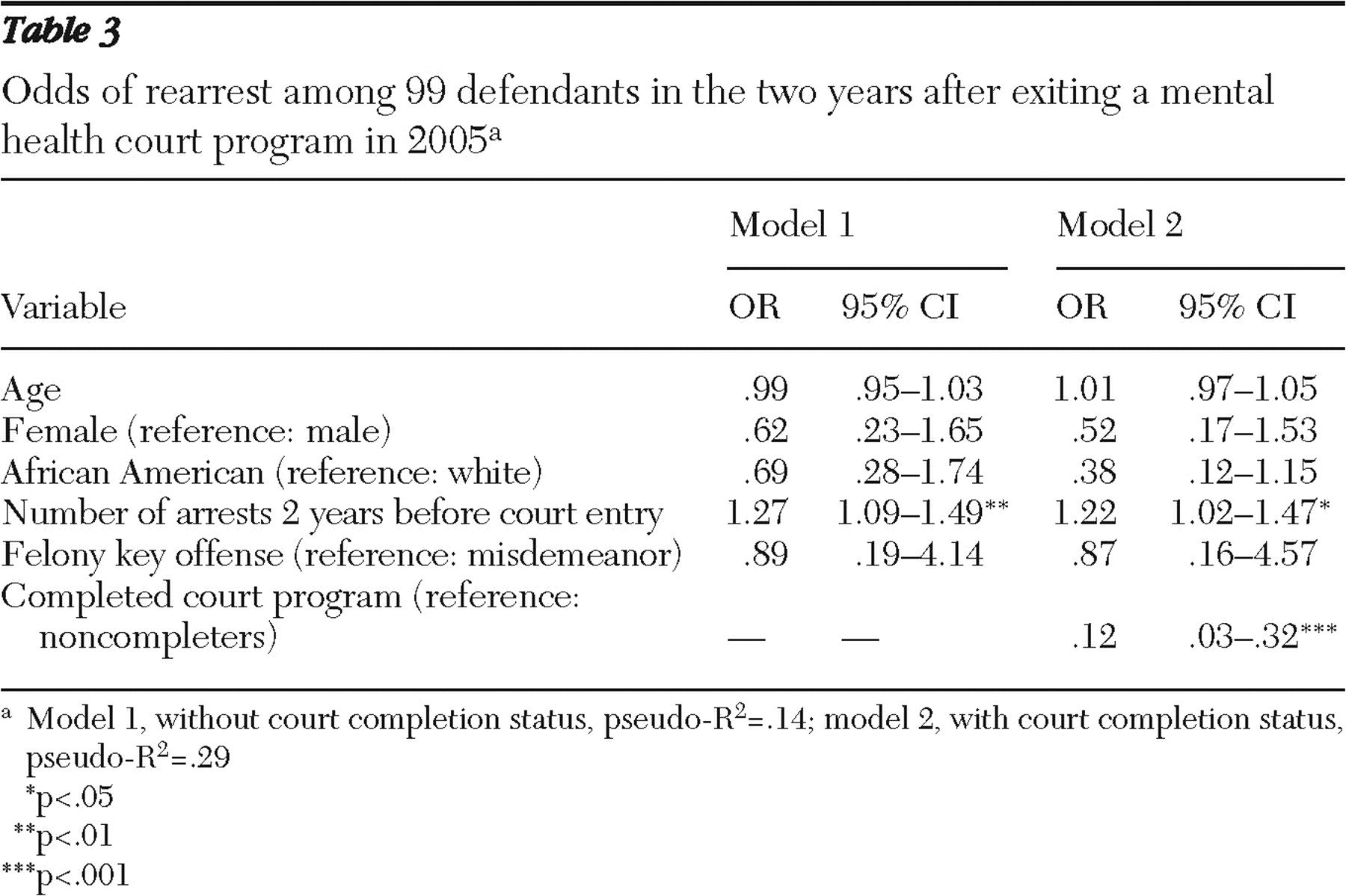

To discern whether completing mental health court affected recidivism when relevant variables were controlled for, we used logistic regression to predict the probability of rearrest in the two years after court exit.

Table 3 presents the results of our multivariate models. Model 1, without factoring in court completion status, showed that only one of the common predictors of arrest, number of prior arrests, was significant (odds ratio [OR]=1.27); for each additional prior arrest, the odds of rearrest increased by 27%. Model 2, which considered court completion status, showed that completing mental health court, as opposed to being ejected from or opting out of the program, reduced the odds of rearrest significantly (OR=.12). When analyses controlled for other independent variables in the model, those who completed the court process were 88% less likely to be rearrested than those who did not.

To examine differences in time to rearrest, we used the Cox proportional hazards model, a type of survival analysis that allowed us to model the time expected to elapse before an event while controlling for all predictor variables from model 2 in the logistic regression analysis. In predicting time to first rearrest in the two-year follow-up, we found that only completion of the mental health court process was statistically significant (OR=.23, p<.001, model not shown). The survival analysis also generates a "life table" that calculates the probability that a terminal event (rearrest in this case) will occur at specified time intervals.

Figure 1, a graphic presentation of the life table, shows the estimated cumulative probability of rearrest for completers and noncompleters. The cumulative survival rate across the y-axis illustrates the proportion of defendants who had not yet been rearrested across 24 months. As shown in the figure, noncompleters had a significantly shorter time to rearrest. The distance between the curves is the estimated long-term positive effect of completing mental health court at any time point. For example, at five months 46% of noncompleters had been rearrested, compared with only 8% of those who completed the process. This figure also illustrates that the greatest likelihood of rearrest for noncompleters was within the first six months after court exit, at which point the likelihood of rearrest slowed. At 20 months, rearrest leveled off, but by then approximately 80% of noncompleters had been arrested.

Discussion and conclusions

This study adds to the accumulating evidence of the effectiveness of mental health courts in reducing recidivism among offenders with mental illness. It went further than all but one earlier study in examining whether a mental health court's impact continues beyond court exit. It found that two years after defendants exit the court, the proportion of defendants rearrested and the mean number of rearrests were significantly lower than in the two years before their mental health court entry. This finding suggests that mental health courts can affect recidivism for a sustained period even though defendants are no longer being monitored by the court and receiving its treatment and services.

As expected, defendants who completed mental health court made the greatest gains. Completers had fewer arrests, a smaller proportion of the group was arrested, and they had a longer time to rearrest than noncompleters. In having continuous and consistent compliance with their individual court mandates for at least six months, completers experienced a full plan of what the court team deemed necessary for each.

Unlike McNiel and Binder'a study (

14 ), our study followed noncompleters as well as completers after their exit from the mental health court program. Notably, even those ejected from the program had fewer rearrests after court exit than before their court entry. Those ejected spent some period receiving treatment and experiencing other elements of the court program. Although not all of them engaged in their individualized treatment, some did and were likely influenced by it even after they left the program.

In interpreting these results, our study's limitations should be kept in mind. First, we did not control for jail time, which removes defendants from risk of arrest; however, given that 90% of our sample was charged only with misdemeanors in their key arrest—as happens with most offenders with mental illness (

3 )—and given that this jurisdiction has a policy of pretrial release for such arrestees (

15 ), jail time would be brief and not likely to affect this study's arrest rates. Because of noncompleters' higher arrest rates, any effect of jail time would cause an underestimation of differences between them and completers and thus an underestimation of the court's effect. Second, we did not control for substance abuse, which is high among offenders with mental illness and is a major explanatory factor in offending (

19,

20,

21 ). Although all defendants with such problems received substance abuse treatment, it is likely that substance use disorders influenced court completion and rearrests after defendants exited the mental health court program.

Third, our study, like other outcome studies of mental health courts, is of a single court in a jurisdiction having two small towns with university and rural communities; thus caution should be taken in generalizing to courts in different environments. Nonetheless, we observed similar processes in team meetings and open court in the mental health courts of central cities in San Francisco, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. Studies of these three courts, as in our study, found reduced criminal recidivism (

14,

22,

23,

24 ).

Fourth, we had no control group with which to compare our sample. We would have liked to have had a randomly selected control group of defendants with mental illness who were matched on relevant variables and who received all needed treatment and services and yet who did not get the mental health court's structure, monitoring, support and sanctions, but only one study has been able to overcome the difficulties of achieving this ideal (

10,

11 ). Fifth, our measures did not include psychological and social characteristics that differentiated completers and noncompleters, and these characteristics probably interacted with components of the mental health court program to influence both completion of the program and recidivism afterward.

Our study's court had the broad features hypothesized to make a mental health court succeed in reducing recidivism: a "carrot" to encourage participation and compliance (the opportunity to have charges dismissed or sentences reduced), a "stick" to enforce compliance with court mandates (the monitoring and sanctions of a judge and court team), aids to reduce effects of mental illness and lack of resources (individualized treatment plus other needed services such as housing and employment assistance), and encouragement to fulfill court mandates (by a supportive team of mental health and legal professionals) (

5,

6,

7,

22,

25 ). It is thus no surprise that the success rate of this court is high: at least three-fourths of defendants had six months or more of not reoffending while they were participating in mental health court, and over half of all participants had no rearrests in the two years after exit from the court program (

9,

10,

11,

12,

14 ).

Other than examining these broad features of mental health courts, empirical studies have not identified specific mechanisms of the court or specific characteristics of defendants that promote compliance with mandates for treatment and behavioral change and that influence resistance to the point of ejection. Because our study was of only one mental health court, all defendants experienced the same judges, court officers, court structure, and court processes; therefore, the likely factors affecting their completion and later recidivism are defendant characteristics, such as substance abuse, social capital, insight into their mental illness, and motivation to change, plus the appropriateness and quality of their individualized treatment and services. Future research on single courts should examine these mechanisms; they have important implications for screening, intake, monitoring, support, and provision of services. Research also needs to be conducted on multiple courts in a single study to permit investigation of the impact of variation in court organization and process on criminal recidivism.