Atypical Depression

The particularly interesting result from this study was the identification of depressive classes defined principally by the atypicality of the symptoms reported. Depressive symptoms with an atypical character or a “reversed functional shift”

(5) (i.e., appetite increase, weight gain, hypersomnia, and psychomotor agitation) constituted one side of the atypicality dichotomy. The symptoms that contributed to the other side of this dichotomy were typical, or vegetative, in nature (i.e., appetite decrease, weight loss, insomnia, and psychomotor retardation) resembling a “functional shift”

(33).

Our principal interest in conducting this study was whether our prior finding in the VTR

(16) could be reproduced in a different sample by a similar analytic approach (i.e., the use of LCA and similar item definitions). The NCS and the VTR are similar in that both are population based and used structured diagnostic instruments. However, these similarities are overshadowed by many differences:

1. The NCS was a probability sample of the continental U.S., whereas the VTR consisted solely of twins born in Virginia.

2. The NCS consisted of male and female subjects of any ethnicity aged 15–54 years, whereas the VTR report was on Caucasian women aged 22–59 years.

3. The NCS depressive symptoms were for the lifetime worst episode of at least 2 weeks’ duration, whereas the VTR data were for a period in the prior year that had lasted at least 5 days.

4. Depressive symptoms were coded for all VTR subjects but only for a subset of the NCS participants.

5. Although the NCS interview (based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview) and VTR interview (based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

[34]) both assessed the DSM-III-R criteria for major depression, the two interviews were considerably different in structure, item wording, and format.

Thus, given that the dissimilarities were greater than the similarities between the VTR and the NCS, it is notable that we were able to reproduce the existence of the atypical classes, one of the key findings from our prior report

(16).

In the depression treatment literature, the clinical importance of identifying a subset of depressed patients with atypical symptoms is supported by expert opinion

(8,

9) and clinical trials

(10–

1235), although not in all studies

(5). Patients with atypical depression may constitute a distinct neurobiological subset

(36). However, given the many different uses of the term atypical over time

(6,

7), a critical question is the degree to which the atypical subtype of depressive symptoms identified in this study and in our prior report (16) overlaps with the Columbia/DSM-IV definitions.

We possess insufficient information to answer this question as we lacked data on all elements of the Columbia/DSM-IV criteria for atypical depression (i.e., mood reactivity, leaden paralysis, and enduring rejection sensitivity). The atypical subtypes we identified were characterized by appetite increase, weight gain, hypersomnia, and, to some extent, psychomotor retardation, which overlap with the Columbia/DSM-IV criteria. Of note, the focus on mood reactivity in the Columbia/DSM-IV criteria is not found in other definitions of atypicality that highlight instead symptoms of a reversed functional shift

(4,

5,

8,

9).

If the overlap between the clinically and epidemiologically defined atypical depressive symptoms is reasonable, these convergent findings—epidemiological dissection of atypical classes in several distinct studies—combined with the clinical utility of atypical depressive symptoms, constitute a compelling rationale for the existence of an atypical subtype and its inclusion in any typology of unipolar depression.

Comparing the NCS and VTR Results

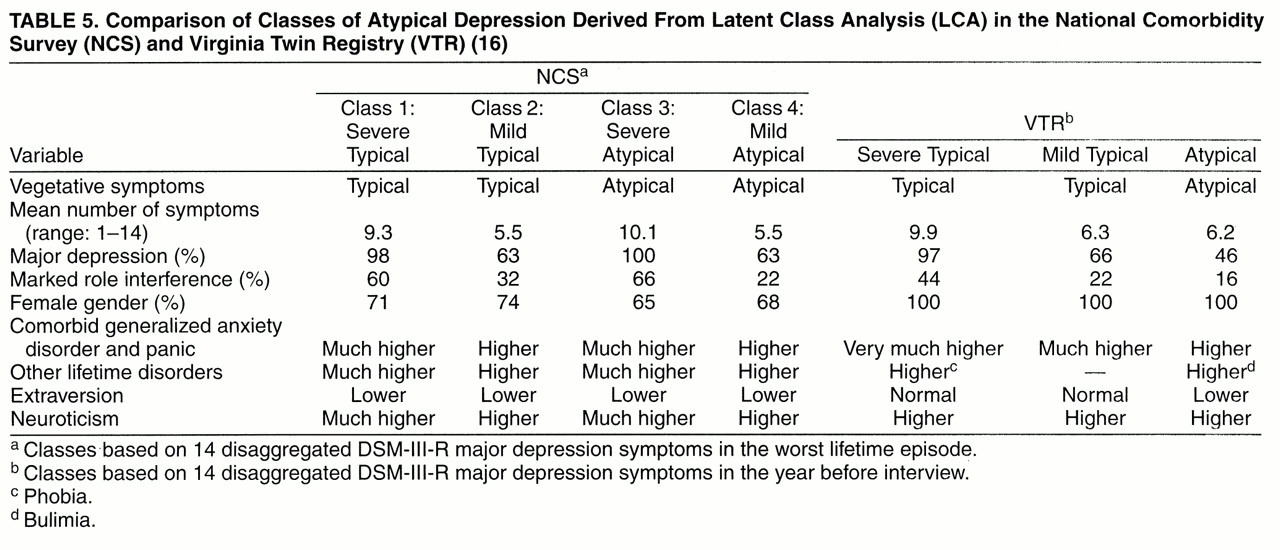

To facilitate comparison,

table 5 summarizes the results of this NCS-based investigation and the VTR report

(16). The VTR report described severe and mild typical LCA classes that were fairly similar to their NCS counterparts in symptoms, mean number of symptoms, the proportion with major depression, and the proportion reporting role interference. The VTR atypical class was most similar to the NCS mild atypical class. The NCS severe atypical class had no counterpart in the VTR, perhaps because the NCS was larger or used a longer time frame.

Kendler et al.

(16) noted several differences between the VTR atypical class and the other classes—i.e., the atypical class was less likely to have comorbid general affective disorder and panic disorder and had decreased extraversion. With the identification in the NCS of a severe atypical class as well as a mild atypical class (similar to the VTR atypical class), the differences in the VTR appear to be more related to severity than to atypicality. The NCS results also differ from those of the VTR in that neuroticism was elevated in the NCS classes, particularly in the severe classes. The VTR report also noted that the atypical class had increased body mass index, risk of bulimia, moderate risk of future major depression, moderate symptom stability over time, and high monozygotic twin concordance. These data were not available in the NCS.

Typical Versus Atypical Depression

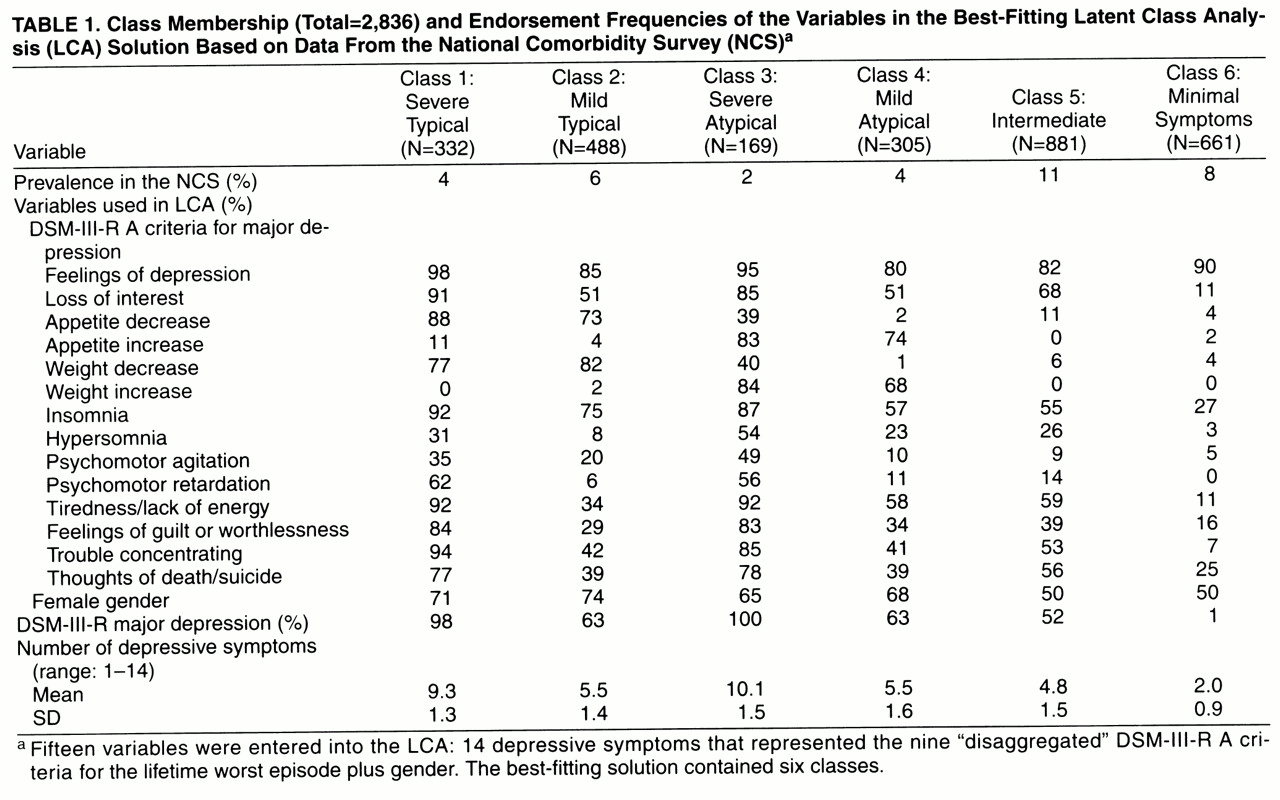

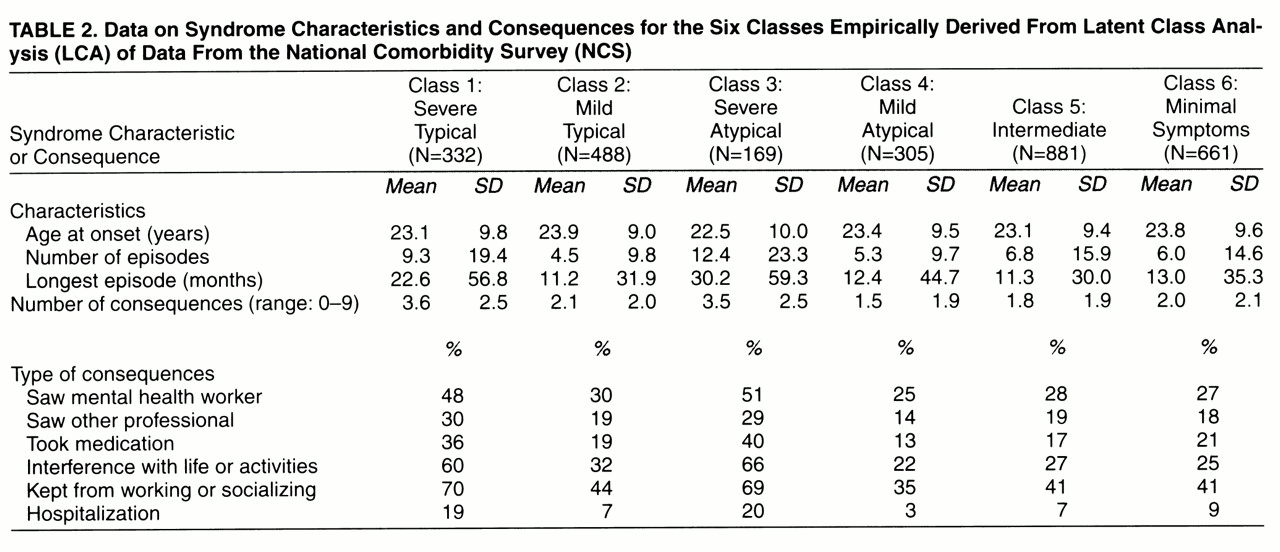

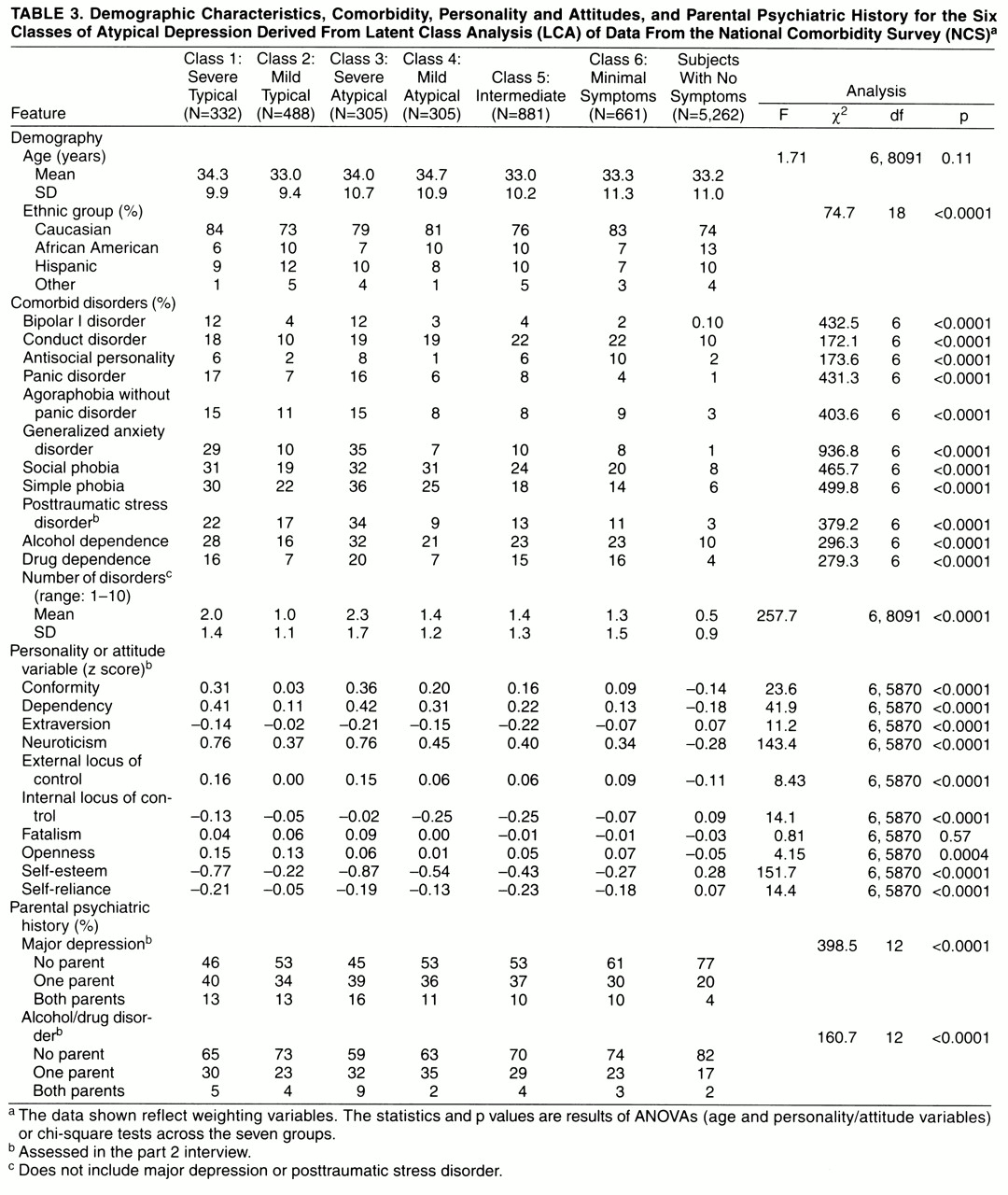

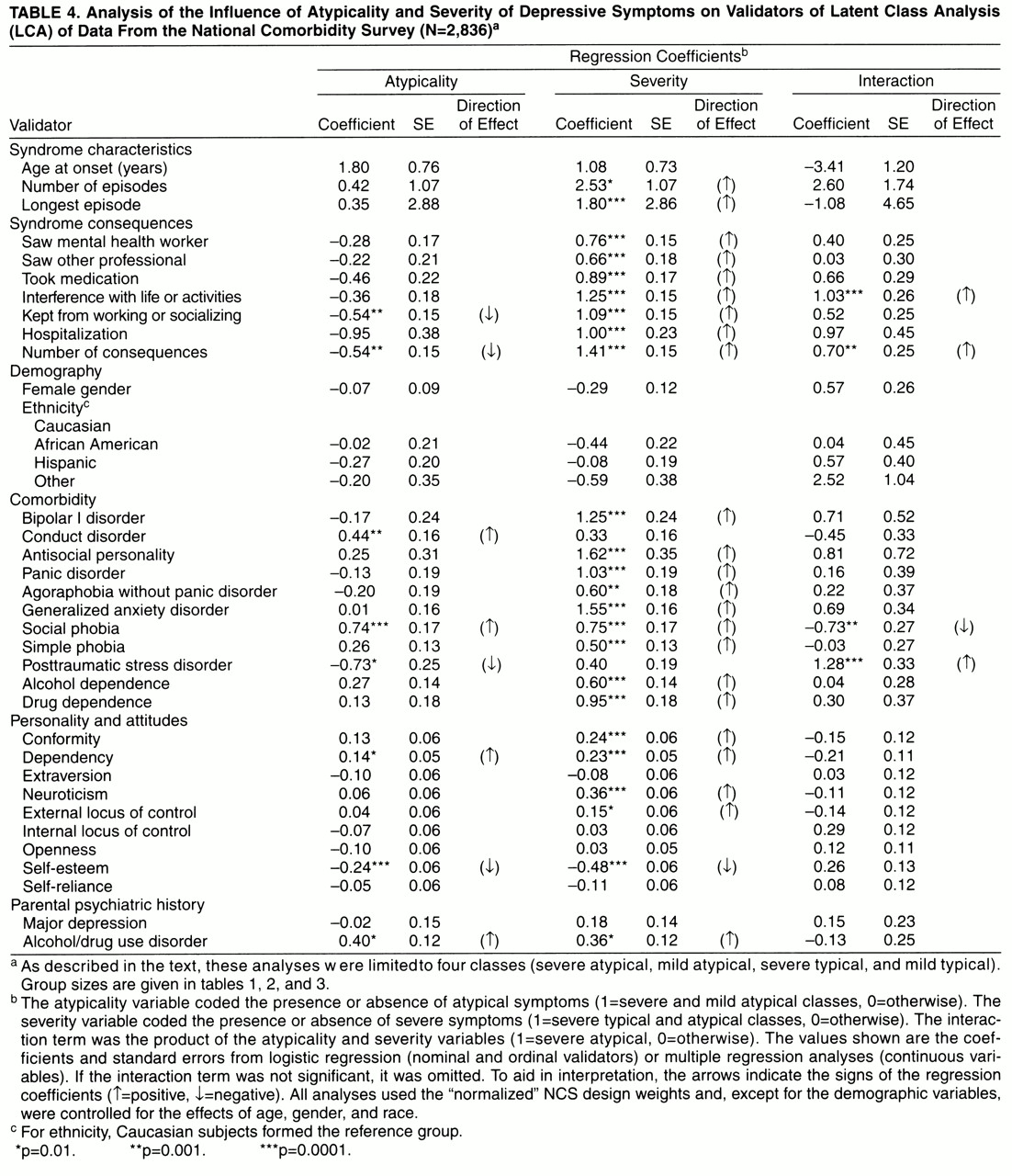

Perhaps the most informative comparisons are those between atypicality and severity (tables 3 and 4). Most differences across the four classes defined by atypicality and severity were related to severity. The main effect of severity (

table 4) was associated with worse episodes, more syndrome consequences, increased comorbidity, more deviant personality traits, and a parental history of alcohol/drug use disorders. These differences were in the anticipated direction and validated the severe versus mild LCA class distinction.

The main effect of atypicality was less frequently significant, although the atypical classes were characterized by decreased syndrome consequences, comorbid conduct disorder and social phobia (but decreased PTSD), higher interpersonal dependency and lower self-esteem, and a parental history of alcohol/drug use disorder. These results suggest that atypicality—although unexpectedly similar to typicality—may have several distinct characteristics. The association of atypicality with parental alcohol/drug use disorders is reminiscent of Winokur’s depression spectrum disease

(37).

We expected to find that the atypical classes were characterized by a distinct personality profile—perhaps akin to neurotic depression

(3). Although atypicality had little impact on many personality/attitudinal attributes, the atypical classes had greater interpersonal dependency and lower self-esteem suggesting that there may be a specific personality typology associated with atypical depression.

From some prior studies of atypical depression

(2,

4,

36), we expected to find an overrepresentation of women in the severe and mild atypical classes. As in other reports

(13,

14), we identified no significant gender differences.

Intermediate and Minimal Symptom Classes

The occurrence of these “subthreshold” classes (together comprising 19% of the subjects in the NCS) and the rather high proportion of each class that reported recurrent and enduring symptoms along with help-seeking behavior or marked symptom consequences were surprising. We know little about the so-called minor depressive disorders. The characteristics of these classes—particularly the equal gender ratio—would argue for further specific study.

We put forward three speculations about these classes. First, studies from the NCS

(38) and the VTR

(39) suggest that depressive states that do not quite meet the DSM-III-R criteria differ from more definitive major depression quantitatively and not qualitatively. These classes might represent

formes frustes of major depression. In addition, subsyndromal depressive symptoms are associated with considerable social morbidity

(40,

41) and an increased risk for first-onset major depression

(42). Second, as the diagnosis of major depression in epidemiological samples has modest reliability

(43,

44), these classes might contain individuals who in fact had major depression but who were coded as having subthreshold symptoms. Finally, these two classes were notable for their increased prevalence of alcohol and drug dependence; depressive symptoms could have represented substance-induced mood disorders.