The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorder has become an increasingly prominent clinical and research concern. Patients who seek treatment for either PTSD or substance use disorder have relatively high rates of comorbidity for the other disorder. Specific estimates depend on the population surveyed, the time frame, and the assessments used (

1). Estimates of the rate of current DSM-III-R-defined PTSD in mixed-gender groups of subjects with substance use disorder range from 12% to 34% (

2–

4). Higher rates—43%–59%—have been reported in studies of women alone (

3,

5,

6), perhaps reflecting women's higher rate of PTSD in general and higher rate of PTSD once they are exposed to trauma (

7,

8). Studies have shown high rates of PTSD among patients with substance use disorders as well as high rates of substance use disorders among patients with PTSD. Three major community studies (

8–

10) that used DSM-III-R criteria, each of which surveyed 1,500–3,400 women, found that drug use disorder was 3.1–4.5 times more likely and alcohol use disorder was 1.4–3.1 times more likely among women with PTSD than among women without PTSD.

Moreover, “harder” substances (i.e., cocaine and opioids) consistently show a higher association with trauma and the diagnosis of PTSD than do other substances such as marijuana or alcohol (

2,

4,

5,

11–

14). Even a family history of substance use problems is a risk factor for exposure to traumatic events (

7).

With greater awareness of the prevalence of these co-occurring disorders has come increasing attention to assessment (

15,

16) and treatment concerns. Treatment programs have begun to be developed specifically for such patients (

13,

17–

19), and several studies have explored these patients' clinical characteristics. Rounsaville et al. (

20) found that 31% of 363 opioid addicts had histories of childhood trauma and that this subgroup showed more impaired psychological, medical, employment, family, and social functioning than opioid addicts without histories of childhood trauma. Brady et al. (

21) compared 30 women with PTSD and 25 women without PTSD, all of whom were in substance abuse treatment. They found that women with PTSD had higher Addiction Severity Index scores, higher rates of comorbid affective disorder, and lower compliance with aftercare. Brown et al. (

3) found that patients with PTSD had a higher rate of utilization of inpatient treatment for substance abuse than patients without PTSD. Najavits et al. (unpublished manuscript, 1997) compared 28 women with current PTSD and substance use disorder and 29 women with PTSD alone. The women with dual diagnoses evidenced more criminal behavior and more lifetime risk factors but a lower rate of major depression than the patients with PTSD alone.

The goal of the present study was to explore clinical characteristics of cocaine-dependent patients with and without co-occurring PTSD. Greater understanding of these subgroups may lead to improved case finding, greater awareness of the range of sequelae typical of these two disorders, and more sophisticated treatments. Specifically, we attempted to identify differences between cocaine-dependent outpatients with and without PTSD, using a battery of measures that extends the results reported in the existing literature. The measures included a description of types of traumas and PTSD symptoms experienced; a wide range of substance abuse and psychiatric symptom measures; assessment of interpersonal functioning, cognition, motivation for treatment, and perceived need for treatment; use of self-help groups; and therapists' emotional reactions to the patients.

METHOD

Data for this study were collected during the pilot phase of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study (

22). That study was designed as a randomized, controlled multicenter clinical trial to examine the efficacy of four psychosocial treatments for cocaine-dependent outpatients: individual cognitive therapy (

23), individual supportive-expressive therapy (unpublished manuscript by D. Mark and L. Luborsky), individual 12-step drug counseling (unpublished manuscript by D. Mercer and G. Woody), and group 12-step drug counseling (unpublished manuscript by D. Mercer et al.). During the pilot phase of the study, staff members were trained and study protocols were developed.

Subjects in the study were 122 adult outpatients who completed two trauma measures, the Trauma History Questionnaire (

24) and the PTSD Checklist (unpublished manuscript by F.W. Weathers et al., 1993). (These measures were completed by only 122 of the 313 subjects in the pilot phase of the NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study because of the late addition of the measures to the assessment battery.) All subjects met the DSM-III-R criteria for cocaine dependence, and all had used cocaine in the past month. All had volunteered for the study to obtain free treatment and provided written consent for the research after its nature had been explained to them. Potential subjects were excluded if they required psychopharmacological or psychosocial treatment outside the study's protocol; had a history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or organic mental disorder; were mandated to attend treatment or were about to be incarcerated; were beyond the first trimester of pregnancy; were currently suicidal or homicidal; had a life-threatening or unstable illness; had had a psychiatric hospitalization of more than 10 days in the past month; were homeless without long-term shelter; or planned to leave the area within 2 years. Patients with substance use disorders other than cocaine dependence were included if cocaine was their primary drug of choice and they did not meet the DSM-III-R criteria for current opioid dependence.

Substance use disorder diagnoses were determined at baseline with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (

25), administered by diagnosticians with master's- or doctoral-level degrees. The SCID diagnosticians were selected and trained by the University of Pennsylvania Assessment Unit of the Center for Psychotherapy Research; all had conducted at least 10 axis I and axis II SCIDs before being hired for this research, and all were evaluated and supervised weekly on the basis of videotapes of their SCID interviews.

All patients participated in three phases of treatment. The initial stabilization phase consisted of individual case management two to five times per week and group drug counseling three times a week (lasting 1–8 weeks). During this time, patients were required to provide three consecutive urine samples that were clear of all substances of abuse and to complete a diagnostic assessment in order to progress to the next phase of treatment, the active phase. The active phase consisted of 32 sessions of group drug counseling and 36 sessions of individual treatment (either individual cognitive therapy, individual supportive-expressive therapy, or individual drug counseling) over 6 months. A final booster phase of three to six sessions over 3–6 months was provided to help patients maintain their gains in treatment. Treatments were not tailored in any way for PTSD.

Patients completed assessments at intake (their first contact with the study), at baseline (at the end of the stabilization phase, as part of the process of random assignment to a treatment in the active phase), and monthly thereafter. They were required to undergo observed urine sampling for drug screens at the time of each group session.

Measures

The measures used in the current study were part of the larger battery of measures used in the pilot phase of the NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. For assessment of trauma history and diagnosis of PTSD, two measures were used, both of which were completed at baseline and were self-report in format because of constraints on interview staff resources. The Trauma History Questionnaire (

24) lists 23 traumatic events in three categories: four crime-related (e.g., mugging, robbery, witnessimg a house break-in), 13 general disasters and trauma (e.g., a car accident or natural disaster), and six unwanted physical and sexual experiences (e.g., rape and physical assault). For each item, patients indicated lifetime occurrence, frequency, age at first occurrence, and any relationship to the perpetrator. Psychometric data on the Trauma History Questionnaire have shown high test-retest reliability of items over a 2- to 3-month period; correlations (Pearson's r) on items ranged from 0.47 to 1.00, with a mean of 0.70 (

24).

PTSD symptoms were assessed with the the PTSD Checklist, on which patients used a 5-point scale to rate the degree to which they had experienced each DSM-III-R PTSD symptom in the past month. The PTSD Checklist was given only to patients who endorsed at least one trauma on the Trauma History Questionnaire. Psychometric data on the PTSD Checklist indicate high test-retest reliability over a 3-day period (r=0.96), high internal consistency (r=0.97), strong convergent validity with other PTSD assessments (with the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, r=0.93; with the PTSD-Keane scale of the MMPI-2, r=0.77; with the Impact of Event Scale, r=0.90; and with the Combat Exposure Scale, r=0.46), and good diagnostic utility with the SCID (sensitivity=0.82, specificity=0.83, kappa=0.64) (unpublished manuscript by F.W. Weathers et al., 1993). To receive a DSM-III-R diagnosis of PTSD for the purpose of this study, patients had to have at least one traumatic event on the Trauma History Questionnaire (to satisfy criterion A of the DSM-III-R PTSD diagnosis) and to have scores of 3 or higher on the PTSD Checklist items that represent criteria B, C, and D of the DSM-III-R PTSD diagnosis (specifically, one criterion B intrusive symptom, three criterion C avoidance symptoms, and two criterion D arousal symptoms).

Other domains assessed in the present study were psychiatric status, substance use, sociodemographic characteristics, and treaters' reactions to patients (all self-report measures unless otherwise indicated). Psychiatric disorders and symptoms were assessed with the SCID items for axis I substance use, affective disorder, anxiety disorder, and eating disorder and axis II disorders (

25); the Beck Depression Inventory (

26); the Beck Anxiety Inventory (

27); the Brief Symptom Inventory (

28); the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

29); the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (DSM-III-R) (rated by trained research assistants); and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (

30).

Substance use measures were as follows. Urine specimens for drug screens were obtained twice weekly for the first 2 months after random assignment to treatment and once a week for the following 4 months. The urine screen results for a week were counted as negative only if all scheduled urine screens were done that week (i.e., none was missing) and all were negative. If any scheduled urine screen was positive for cocaine, all screens that week were counted as positive. Missing urine screens were assumed to be positive for cocaine, thus providing a conservative estimate of drug use. Results of supervised urine screens were analyzed at a NIDA-approved laboratory that used an enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique and gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy confirmation of positive results. A total score was determined as the percent of positive urine screens across the stabilization phase for cocaine alone and also for any of six types of drugs (cocaine, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, marijuana, and opioids).

The Addiction Severity Index—5th edition (

31) interview was administered by research assistants to assess the severity of drug and alcohol use and five related problem areas (family/social, legal, psychological, employment, and medical). The Addiction Recovery Scale (unpublished scale by D. Mercer et al.) measured attitudes and behaviors relevant to recovery from substance dependence. The Beliefs About Substance Abuse Scale (unpublished scale by F. Wright) assessed thoughts associated with substance use. The Relapse Prediction Scale (unpublished scale by F. Wright) listed situations, such as being at a party, for which the patient rated the strength of substance use urges and the likelihood of using. The Weekly Self-Help Scale (unpublished scale by R.D. Weiss and J. Albeck) assessed the number of and participation in self-help activities. The research version of the Recovery Attitudes and Treatment Evaluator—Clinical Evaluation (

32) evaluated motivation for addictions treatment by means of a structured interview conducted by trained research assistants.

Sociodemographic information was obtained from the Cocaine Inventory (unpublished scale by Bristol-Myers Squibb), a measure of sociodemographic data as well as data on current and lifetime substance use, cravings, and likelihood of use. Treaters' emotional reactions to patients were assessed with the Ratings of Emotional Attitudes to Clients by Treaters (

33).

All of the substance use measures were analyzed for patients in the study who had completed both the Trauma History Questionnaire and the PTSD Checklist. Most of the measures were completed at baseline, but the Addiction Severity Index was completed at intake, the Weekly Self-Help Scale was completed weekly during the stabilization phase, ratings of treaters' emotional reactions were completed at session 5 after random assignment to treatment, and urine screens were done up to three times per week during the stabilization phase.

Analyses

Data analyses were organized by three main questions: 1) What are the sociodemographic and substance use characteristics of the study group? 2) What is the prevalence of traumatic events and PTSD diagnoses in the group (and how do these vary by gender)? 3) How do cocaine-dependent patients with PTSD compare to those without PTSD on a variety of objective and subjective measures? The first two questions were addressed by descriptive statistics. For the third question, two sets of analyses were conducted. The first was a simple analysis that used independent t tests and chi-square tests, with the familywise Bonferroni correction to decrease the type I error rate. The second was a more conservative analysis that used logistic regression. We selected, with replacement, 300 bootstrap (

34) samples of size 122 from the 122 study subjects. For each sample, a forward stepwise logistic regression model was chosen with the 13 candidate independent variables that were significant predictors of PTSD in univariate analyses (determined by the previous “simple” analysis) and had no more than 10 missing observations. (The 13 variables that met these criteria are indicated by footnote e in

table 1.) To control the variable-to-sample size ratio (

35), the forward selection process was stopped at four variables. Specificity was set as close to 0.70 or above as possible, separately by sample (tied values of covariates precluded choosing precisely 0.70).

RESULTS

Sixty-five percent of the subjects were male; the mean age was 32.6 years (SD=6.2). Sixty-two percent of the subjects were Caucasian, 34% African American, and 4% Hispanic. Fifty percent were single, 28% were married or cohabiting, and 21% were separated or divorced. More than half of the subjects (57%) were employed. They reported using cocaine on a mean of 11.7 days (SD=8.7) and spending an average of $1,493 (SD=$1,671) on cocaine during the month before entering the study.

Twenty-five patients (20.5%) had a current DSM-III-R diagnosis of PTSD (based on the Trauma History Questionnaire and the PTSD Checklist). The rate of PTSD by gender was 30.2% (N=13 of 43) for women and 15.2% (N=12 of 79) for men. For all patients, the mean number of lifetime traumas was 5.7 (SD=3.9) out of the 23 listed on the Trauma History Questionnaire. By categories of traumatic events, the most frequent were general disasters and trauma (mean=3.2 events, SD=2.4), followed by crime-related events (mean=1.2, SD=1.1), and physical/sexual events (mean=1.2, SD=1.4). Men had significantly more general disasters and trauma (mean=3.9 for men versus mean=2.0 for women; t=4.32, df=116, p<0.001) and crime-related events (mean=1.4 for men versus mean=0.9 for women; t=2.38, df=115, p<0.02). Women had significantly more physical and sexual traumas (mean=0.9 for men versus mean=1.7 for women; t=–2.87, df=115, p=0.01).

The groups with and without PTSD did not differ significantly on sociodemographic variables (age, marital status, ethnicity, employment status, and gender).

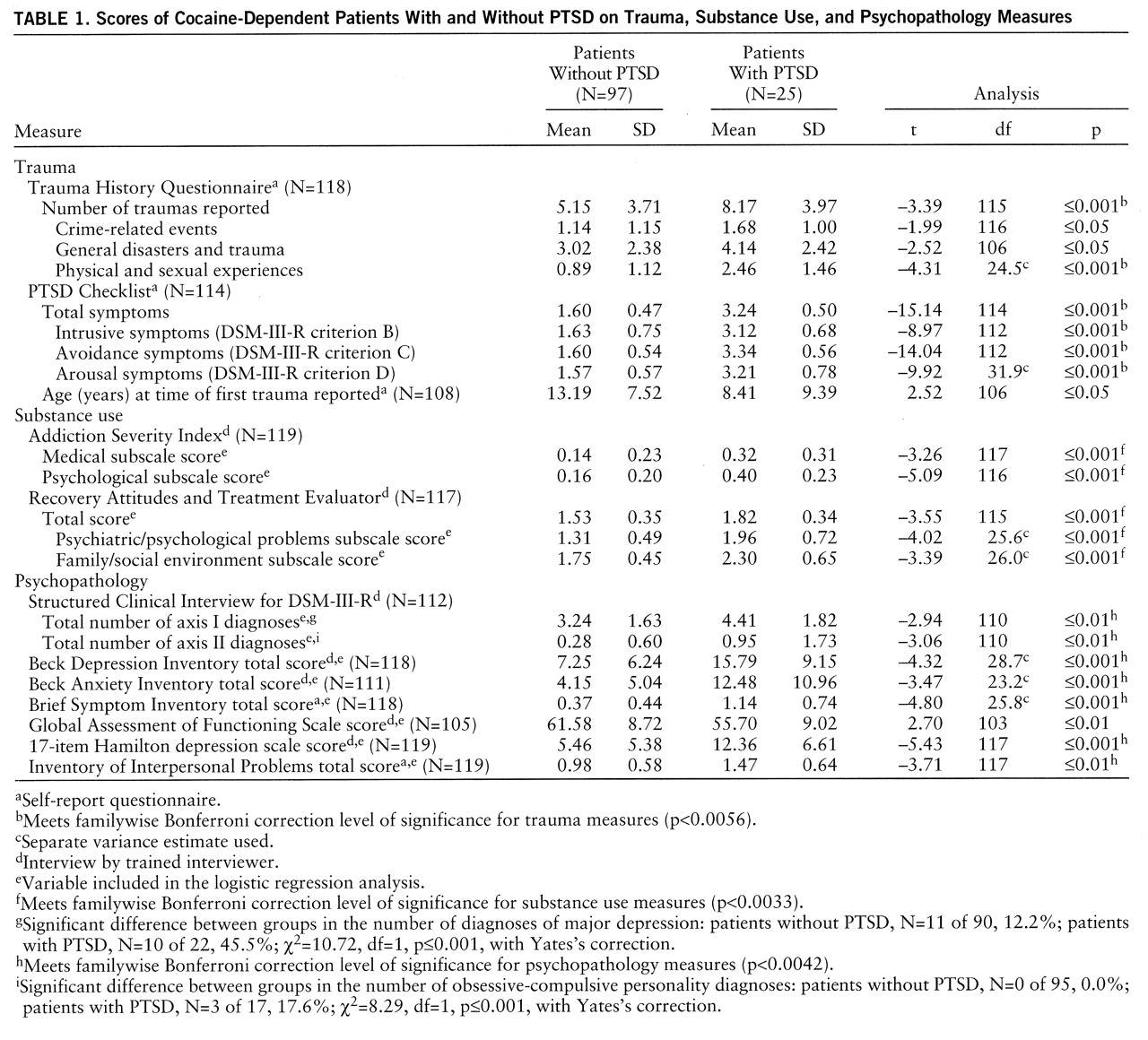

Independent t tests were conducted as a first, basic comparison of the PTSD and non-PTSD groups on the main study variables. Results of this analysis are displayed in

table 1 and indicate that in all of the comparisons of the PTSD and non-PTSD groups in which there were significant differences, the group with PTSD was more symptomatic. A summary of specific results (referencing only those results that reached the Bonferroni level of significance to control for type I error) follows.

Not surprisingly, the two groups differed on the trauma measures, that is, the Trauma History Questionnaire and the PTSD Checklist (both of which were used to define the PTSD diagnosis).

Within the substance use domain, the PTSD and non-PTSD groups differed on five variables: the Addiction Severity Index medical and psychological subscale scores and the Recovery Attitudes and Treatment Evaluator total score and psychiatric and family/social subscale scores.

On psychopathology measures, the two groups were significantly different on virtually all variables analyzed. That is, the group with PTSD was more severely ill according to the total number of axis I disorders on the SCID (and also the proportion of subjects with major depression), the total number of axis II disorders diagnosed on the SCID (and also the proportion of subjects with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder), the Beck Depression Inventory score, the Beck Anxiety Inventory score, the Brief Symptom Inventory total score, the 17-item Hamilton depression scale score, and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems score. Also, on the Addiction Severity Index, the patients with PTSD reported that treatment for psychological problems was more important than did the non-PTSD patients (t=–5.17, df=112, p<0.001).

The groups with and without PTSD did not show significant differences on the following measures: percentage of positive screens for cocaine or any drug; the Addiction Severity Index employment, alcohol, drug, legal, and family/social subscales; the Addiction Recovery Scale; the Beliefs About Substance Abuse Scale; the Relapse Prediction Scale; the Weekly Self-Help Scale; the percentage attending self-help meetings; the Recovery Attitudes and Treatment Evaluator resistance to treatment, resistance to continuing care, and biomedical problems subscales; and the Ratings of Emotional Attitudes to Clients by Treaters.

We also conducted a logistic regression to evaluate more conservatively which among the 13 variables found to show significant differences between groups (

table 1) were most consistently related to the PTSD diagnosis. Of the 300 bootstrap runs, the most common model contained only the Beck Depression Inventory total score and the Brief Symptom Inventory global scale score, with sensitivity at 80%.

DISCUSSION

Our results can be summarized as several main findings. We found a 20.5% rate of PTSD (based on self-reports) in this study of cocaine-dependent outpatients. When the results were analyzed by gender, women had the highest rate of PTSD (30.2%); the rate for men was 15.2%. Patients with PTSD were more symptomatic than non-PTSD patients in every comparison of the two groups in which there was a significant difference. The most consistent finding was in psychopathology symptoms, a domain in which the groups with and without PTSD differed significantly on nearly every variable. Moreover, the Beck Depression Inventory and the Brief Symptom Inventory provided a particularly consistent and sensitive prediction of PTSD status in the logistic regression bootstrap analysis (our more conservative test of the PTSD versus non-PTSD groups). Surprisingly, however, the patients with PTSD did not differ from the patients without PTSD in sociodemographic characteristics or current substance use. We also found that across the study group as a whole, the men had a higher number of general disasters and crime-related traumas than the women, and the women had a higher number of physical and sexual traumas. The mean number of lifetime traumas (5.7) in the full study group was remarkably high.

To our knowledge, these results are the first published account of PTSD symptoms in cocaine-dependent patients, and they provide a broader range of descriptive findings than has previously been available from any study of co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorder. Because patients were studied in the course of a standardized, multisite clinical trial, the level of rigor in patient sampling and diagnostic assessment was high. The sociodemographic characteristics of our patients indicate a racially diverse mix, a relatively high percentage of women for a substance dependence study, and a fairly wide range of addiction severity and employment status. All conclusions, however, must be tempered by the limitations of the study: the small subgroup on which comparisons were made (i.e., there were only 25 patients in the PTSD group), the potential for type I error due to the number of comparisons conducted in some analyses, the use of several scales that have not yet been psychometrically validated, and occasional missing data on some variables. In addition, the use of self-report PTSD measures (albeit with some previous validation with the use of interview methods) precluded clinical judgments to fully ascertain the PTSD diagnosis (for instance, the sometimes difficult determination of whether criterion A was met). The use of various self-report measures may also have capitalized on PTSD patients' tendency to perhaps overreport symptoms.

It is notable that the rate of PTSD in this study is consistent with other published rates in the literature despite variations among studies in sampling and assessment. The finding that the rate of PTSD in the women was twice that in the men is also consistent with the literature. In this study, we might have expected the incidence of PTSD to be underestimated because of 1) the use of self-report rather than an interview method for making that diagnosis, 2) exclusion criteria that may have resulted in these patients being less severely ill than those in other clinical settings (e.g., the requirement that patients not be in concurrent treatments during their participation in this study), 3) assessments that were conducted at the start of treatment when awareness of or willingness to disclose PTSD may have been limited, and 4) the restricted set of outpatients who successfully completed the stabilization phase and reached the randomization phase. We thus speculate that in nonresearch settings, rates of the PTSD/substance dependence dual diagnosis might likely be higher. The high mean number of traumas in the group as a whole—5.7—alerts us to such potential, as well as to the complicated interaction of trauma and substance abuse lifestyles.

A surprising finding was the absence of a difference between the groups with and without PTSD on substance abuse measures and sociodemographic characteristics. It might have been expected that the PTSD subgroup would be more impaired in these domains. The fact that all subjects were volunteers for outpatient substance abuse treatment, however, may have narrowed the range (and thus the ability to find results) in the substance use domain.

With regard to assessment, screening for PTSD in substance-dependent patients may be facilitated by use of brief self-report measures such as those used in this study to obtain a provisional diagnosis of PTSD. Such screening may be particularly important given reports that PTSD is often not assessed in substance abuse treatment settings (

36).

Future research will be needed to confirm these results, as well as to explore the relation between drug of choice and PTSD, to examine change over time in PTSD and substance use symptoms (e.g., does abstinence lead to increased PTSD symptoms?), to unravel the causal order of the two disorders, and to study the relation of these comorbid diagnoses to treatment outcome. We echo the mandate suggested by other writers (

1,

21,

37) for increased clinical and research attention to this important subgroup.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study is a cooperative agreement sponsored by NIDA involving four clinical sites, a coordinating center, and NIDA staff. The coordinating center at the University of Pennsylvania includes Paul Crits-Christoph, Ph.D. (principal investigator), Lynne Siqueland, Ph.D. (project coordinator), Karla Moras, Ph.D. (assessment unit director), Jesse Chittams, M.A. (director of data management/analysis), and Larry R. Muenz, Ph.D. (statistician). The collaborating scientists at the Treatment Research Branch, Division of Clinical and Research Services, NIDA, are Jack Blaine, M.D., and Lisa Simon Onken, Ph.D. The four participating clinical sites are the University of Pennsylvania (Lester Luborsky, Ph.D., principal investigator; Jacques P. Barber, Ph.D., co-principal investigator; and Delinda Mercer, M.A., project director); Brookside Hospital (Arlene Frank, Ph.D., principal investigator; Stephen F. Butler, co-principal investigator; and Sarah Bishop, M.A., project director); Harvard Medical School, McLean Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital (Roger D. Weiss, M.D., principal investigator; David R. Gastfriend, M.D., co-principal investigator; Lisa M. Najavits, Ph.D., project director; and Margaret Griffin, research associate); and the University of Pittsburgh/Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (Michael Thase, M.D., principal investigator; Dennis Daley, M.S.W., co-principal investigator; Ishan M. Salloum, M.D., co-principal investigator; and Judy Lis, M.S.N., project director). The heads of the cognitive therapy training unit are Aaron T. Beck, M.D. (University of Pennsylvania) and Bruce S. Liese, Ph.D. (University of Kansas Medical Center). The heads of the supportive-expressive therapy training unit are Lester Luborsky, Ph.D., and David Mark, Ph.D. (University of Pennsylvania). The heads for individual drug counseling are George Woody, M.D. (Veterans Administration/University of Pennsylvania Medical School), and Delinda Mercer, M.A. (University of Pennsylvania). The heads of the group drug counseling unit are Delinda Mercer and Dennis Daley (University of Pittsburgh/Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic), and Gloria Carpenter, M.Ed. (Treatment Research Unit, University of Pennsylvania). The Monitoring Board consists of Larry Beutler, Ph.D., Jim Klett, Ph.D., Bruce Rounsaville, M.D., and Tracie Shea, Ph.D. The contributions of John Boren, Ph.D., the project officer for this cooperative agreement at NIDA, are also acknowledged.