Numerous follow-up studies have examined the adolescent and young adult fate of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (reviewed in references 1–3). These studies have shown that conduct problems (

4–

7), arrest histories (

8,

9), poor academic histories (

6,

10,

11), and the continuance of ADHD symptoms (

4–

7,

10,

11) are common.

In marked contrast, there have been only two controlled, prospective studies of psychiatric status into adulthood. In their 15-year follow-up study, Weiss et al. (

12) assessed 61 formerly hyperactive probands and 41 comparison subjects at an average age of 25 years. The only DSM-III diagnosis that was significantly more prevalent in the probands than the comparison subjects was antisocial personality (23% versus 2%) (χ

2=8.22, df=1, p<0.01). However, 36% of the probands (versus only one of the 41 comparison subjects) reported at least one moderate to severe symptom of ADHD. Unfortunately, the rate of attrition was high (about 40%), and most of the psychiatric evaluations were not blind.

We reported the only other controlled, prospective follow-up study of ADHD children into adulthood (

13). The original childhood cohort consisted of 103 white boys between the ages of 6 and 12 years. At late adolescent follow-up (average age=18 years), information was obtained on 98% of the childhood cohort through blind interviews by clinicians (

4). Ongoing (i.e., at follow-up) attention deficit disorder was diagnosed in 40% of the probands but only 3% of the comparison subjects (χ

2=40.56, df=1, p<0.0001). Also, 27% of the probands and only 8% of the comparison subjects had ongoing antisocial personality disorder (χ

2=12.50, df=1, p<0.0001). Furthermore, 16% of the probands and 3% of the comparison subjects had ongoing drug abuse syndromes (χ

2=9.83, df=1, p<0.01). Mood and anxiety disorders were rare.

These findings were replicated with an independent cohort of 104 white boys who were seen at the same clinic as the first cohort when they were between 5 and 11 years old (

5). At a mean age of 18 years, information was obtained on 90% of the childhood group by clinicians blind to childhood diagnosis. Ongoing attention deficit disorder was diagnosed in 43% of the probands and 4% of the comparison subjects (χ

2=34.06, df=1, p<0.001). Also, 32% of the probands and 8% of the comparison subjects had ongoing antisocial personality disorder (χ

2=15.11, df=1, p<0.0001). Furthermore, 10% of the probands and 1% of the comparison subjects had ongoing drug abuse syndromes (χ

2=5.35, df=1, p<0.05). Mood and anxiety disorders were rare. The present study was an adult follow-up of these subjects.

Together, the preceding findings point to the serious consequences of early ADHD into adolescence in a substantial proportion of children. The bleak adolescent picture highlights the importance of understanding the adult status of children with ADHD.

At adult follow-up (at a mean age of 25 years), 88% (N=91) of the first cohort of 103 boys were blindly interviewed by trained clinicians (

13). As had been the case in late adolescence (

4), antisocial personality (18% versus 2%) (χ

2=11.03, df=1, p<0.01) and drug abuse (16% versus 4%) (χ

2=7.63, df=1, p<0.01) significantly discriminated the probands and comparison subjects, and mood and anxiety disorders did not. Also, clinically impairing attention deficit disorder symptoms and syndromes were diagnosed in 11% of the probands and 1% of the comparison subjects (χ

2=6.46, df=1, p<0.05).

The present study was conducted to gain further understanding of the natural course of ADHD. It extends previous data by examining the adult status of an independent group of hyperactive boys. On the basis of previous findings (

12,

13), we hypothesized the following:

1. Antisocial personality disorder will be significantly more prevalent in probands than normal comparison subjects.

2. Nonalcohol psychoactive substance use disorder will be significantly more prevalent in probands than comparison subjects.

3. ADHD syndromes and clinically impairing symptoms will be significantly more prevalent in probands than comparison subjects.

4. The prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders will not significantly discriminate the groups.

METHOD

Subjects

Probands. Between 1970 and 1977, over 1,000 children were assessed at a no-cost child psychiatric research clinic (

14,

15). Of these, 207 white boys each met the following criteria: 1) was referred by a teacher because of behavior problems, 2) was judged hyperactive by a teacher, i.e., had a score of at least 1.8 on the hyperactivity factor of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (

16), 3) was judged hyperactive by parents or clinic staff, 4) was diagnosed as having DSM-II hyperkinetic reaction of childhood by a psychiatrist, 5) had an IQ of at least 85, 6) was free of psychosis and neurological disorder, 7) was without clinically significant presenting problems involving aggression or other antisocial behaviors, and 8) had English-speaking parents with a telephone.

In the present article we report on the adult outcome of one of two cohorts, consisting of 104 of the total 207 boys who were evaluated in childhood. The distinction between these two cohorts relates to the age at the evaluation conducted during adolescence. A subject had to have reached his 16th birthday to be evaluated in the adolescent follow-up. Between 1979 and 1982, when the first series of adolescent follow-up interviews was conducted, 103 of the 207 boys met this criterion. The adolescent (

4) and adult (

13) outcomes of this cohort have been previously reported. Between 1984 and 1987, the second cohort was evaluated, and their adolescent outcome was previously reported (

5). The adult outcome of the second cohort is the focus of this article.

When the subjects were initially seen in childhood, systematic evaluations were conducted by child psychiatrists, and diagnoses were recorded in standard fashion (

17). Of the 104 boys in this study, only one was diagnosed as having DSM-II unsocialized aggressive reaction, and none had group delinquent reaction; these two DSM-II diagnoses approximate the current diagnosis of conduct disorder. Thus, conduct disorder was virtually absent, probably since the children were not accepted if aggressive or other antisocial behavior contributed significantly to the clinical picture.

The children were from middle-class homes (mean socioeconomic status=3.0, SD=1.0), were of average intelligence (mean full-scale IQ=105, SD=13), and had very high teacher ratings on the Conners hyperactivity factor (

16) (mean=2.4, SD=0.5, out of a possible 3.0). Their age range was 5 to 11 years (mean=7.3, SD=1.1). Learning disability was rare, occurring in 2%–7% of the children (depending on stringency of criteria).

Comparison subjects. The comparison subjects were recruited at the time of adolescent follow-up from nonpsychiatric outpatient clinics within the medical center. The charts of white males of appropriate age and socioeconomic status were reviewed. Those treated for accidental injuries or chronic, serious illnesses and those for whom behavior problems before age 13 were noted were not pursued. The parents of selected subjects were called and asked whether elementary school teachers had ever complained about their child's behavior. If not, the individual was recruited for adolescent follow-up.

Sixty-four comparison subjects were recruited in this fashion. To enlarge the group, a community-sampling service recruited 14 additional comparison subjects. As with the other comparison subjects, the parents were asked whether teachers complained about the child's behavior in elementary school, and if not, the individual was recruited.

The resulting comparison group for the adolescent follow-up consisted of 78 males 16–21 years of age (mean=18.6, SD=1.5). In spite of attempts to recruit comparison subjects matched to the probands for socioeconomic status, the probands had significantly lower socioeconomic status than the comparison subjects (mean=3.0, SD=1.0, versus mean=2.5, SD=1.0) (t=3.75, df=170, p<0.001), according to ratings on the Hollingshead index (

18).

Adult Follow-Up Assessment

The subjects were administered a semistructured interview that included DSM-III-R antisocial personality, attention deficit, anxiety, mood, substance use, and psychotic disorders (

19). Blind assessments were conducted by a clinical psychologist and a psychiatric social worker, who achieved good to excellent reliability on the major disorders (

13). Kappa values (

20), based on 50 audiotaped interviews conducted by one clinician and diagnosed by the other clinician, were as follows: ADHD, 0.70; antisocial personality disorder, 0.69; substance use disorder, 0.80; major depression, 1.00.

The recruiting social worker explained the study to the subjects and obtained oral consent. Written consent was obtained by the interviewers before the evaluation.

The interviewers wrote narratives, which were blindly reviewed by a senior investigator (S.M.) for diagnostic accuracy.

Psychiatric Status

Probable and definite diagnoses of DSM-III-R disorders were made. Probable diagnoses were defined by the presence of fewer than the required number of symptoms associated with functional impairment. Probable and definite diagnoses are combined in this report. We believe that this procedure is consistent with clinical practice since functional disruption was required at both levels.

In the present paper we report on adult status, i.e., ongoing mental disorders, defined as meeting the criteria within 2 months of the follow-up interview. The only exceptions were personality and substance use disorders, which were considered ongoing if the criteria had been met during the past 6 months. Although any stipulation of “ongoing” is arbitrary, this procedure seems reasonable given the chronic nature of these disorders.

Data Analyses

Logistic regression analyses (

21) were used to assess the effect of group on mental disorders at follow-up. Because of group differences in socioeconomic status, adjusted odds ratios controlled for parental socioeconomic status at adolescent follow-up. The parents', rather than the subject's, socioeconomic status was covaried since the latter might be contaminated by diagnostic status (e.g., antisocial personality with school expulsion and job instability). Age at adult follow-up was also controlled since the probands and comparison subjects differed significantly. Bonferroni corrections were applied to nonhypothesized contrasts (

table 1). One-tailed tests were applied in view of explicit directional hypotheses (

22). Chi-square tests were Yates corrected.

RESULTS

Length of Follow-Up and Group Characteristics

The duration of follow-up ranged from 15 to 21 years (mean=17.0, SD=1.4). Of the original 104 probands, 85 (82%) were directly interviewed. Of those not interviewed, one had died before the adolescent follow-up, 15 (14%) refused to participate, and three (3%) could not be located.

Of the original 78 comparison subjects, 73 (94%) were interviewed at adult follow-up. The remaining five (6%) refused to participate.

The probands were significantly older (mean=24.1 years, SD=1.2, versus mean=23.5, SD=1.1) (t=3.86, df=163, p<0.001) and had significantly lower social class ranks (

23) than the comparison subjects (mean=3.3, SD=0.8, versus mean=2.8, SD=0.8) (t=3.91, df=163, p<0.0001).

Diagnoses

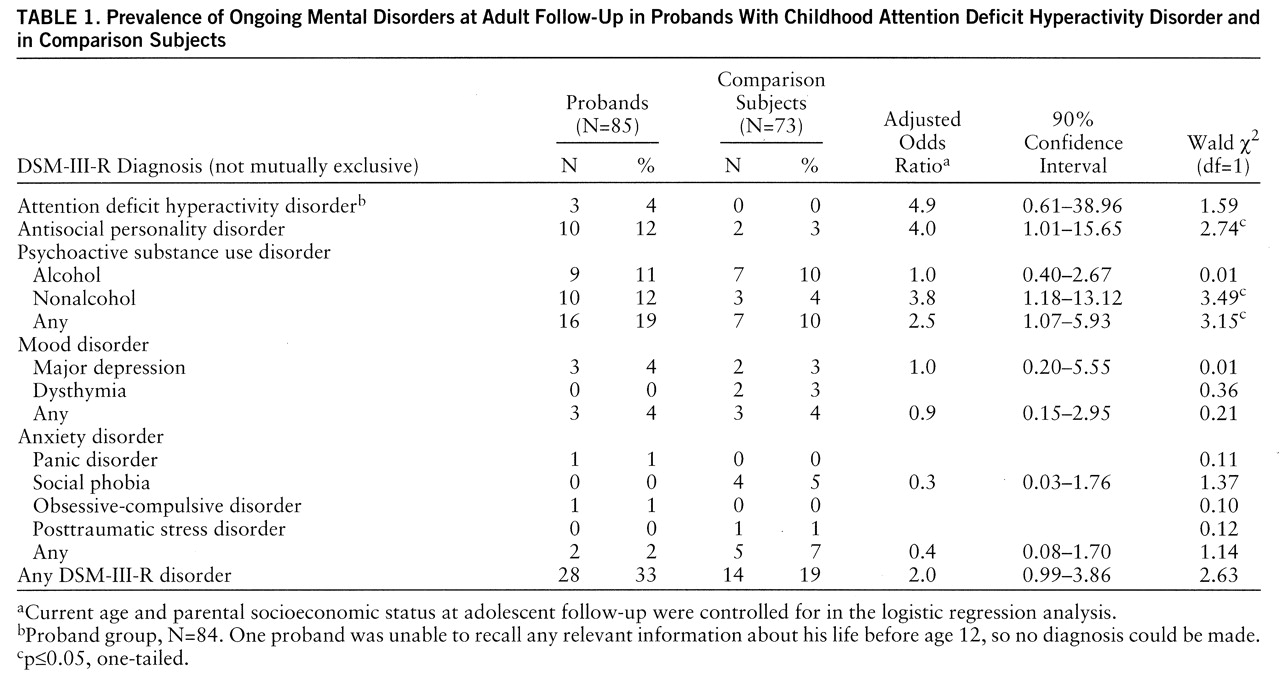

One-third (33%) of the probands versus one-fifth (19%) of the comparison subjects had ongoing mental disorders at adult follow-up. The most common diagnoses in the probands were antisocial personality disorder and nonalcohol substance use disorder (

table 1).

Two probands and none of the comparison subjects were incarcerated at follow-up (for rape and robbery). In our previous study (

13), five probands (and no comparison subjects) were incarcerated, also for aggressive offenses.

Significantly more probands than comparison subjects abused nonalcoholic substances (

table 1). Marijuana was abused by all 10 of the probands with nonalcohol substance use disorder and by two of the three comparison subjects.

The antisocial and substance abuse syndromes aggregated significantly. Sixty percent of the probands with antisocial personality disorder versus 13% of those without antisocial personality had comorbid substance use disorders (χ2=9.71, df=1, p<0.01).

Only 4% of the probands (versus no comparison subjects) had the full ADHD syndrome at follow-up (

table 1), and no subject reported clinically impairing symptoms in the absence of the full syndrome.

The rates of mood and anxiety disorders did not differ significantly between the probands and comparison subjects (

table 1). The rates of mood disorders were nearly identical, and anxiety disorders were more common in the comparison subjects than in the probands. Also, no specific mood or anxiety disorder significantly discriminated the two groups (

table 1).

DISCUSSION

Antisocial Personality Disorder

The prevalence of antisocial personality among probands reported by Weiss et al. (23%) was higher than the rates in our present study (12%) and previous study (18%). However, they stated, “One-third of our DSM-III antisocial personalities were mild and might have been excluded from the diagnosis by some investigators”

(12, p. 216). Given the seriousness of the antisocial behaviors and arrest histories, our probands did not have mild cases.

The probands had significantly lower socioeconomic status than the comparison subjects. However, parental socioeconomic status at adolescent follow-up was covaried in the logistic regression analyses, thus minimizing the possibility that differences in socioeconomic status accounted for the findings on adult outcome.

Nonalcohol Substance Use Disorder

The significantly higher prevalence of drug abuse among the probands in the current study group is consistent with the findings in our previous study (

13). Weiss and colleagues (

12) did not find a higher prevalence of substance abuse in their probands. Although the rates of use of nonalcoholic substances (mainly marijuana) were high in their study (57% of probands, 46% of comparison subjects), none of their subjects was classified as abusing drugs during the 3 months preceding adult follow-up. This difference is puzzling, especially since both studies showed high rates of antisocial personality, which is highly associated with substance abuse. However, the two investigations differed in geographical location (Montreal and New York City) and in timing (early 1980s versus 1990s).

ADHD Syndromes and Symptoms

ADHD was rare. Only 4% of the probands (and no comparison subjects) had the full syndrome, and no probands or comparison subjects had a partial syndrome at adult follow-up. This compares to 11% of the probands in our previous study and the 36% judged to have at least one moderately or severely disabling symptom in the Weiss et al. study (

12).

Our procedure for evaluating ADHD symptoms was as follows. First, we evaluated childhood occurrence. For symptoms that were at least moderately distressing in childhood, their status at adolescence and adulthood was probed. Therefore, if a symptom was reported as only mildly disturbing or as no problem at all in childhood, its presence in adolescence and adulthood was not assessed. Weiss and colleagues asked about current (i.e., adult) functioning regardless of previous functioning. Thus, we might have missed cases in subjects whose childhood symptoms were denied because of poor recall. To correct for the possibility of missed cases, we examined the rate of adult ADHD diagnoses in probands who reported having had ADHD in childhood (N=65). This rate was only 5%, close to the 4% for the entire study group. Therefore, the low rate of adult ADHD does not appear to have resulted from the diagnostic procedures implemented.

Second, whereas we conducted blind assessments, Weiss et al. did not. Therefore, it is possible that unintentional procedural differences found their way into the evaluations (e.g., more detailed inquiry for probands than for comparison subjects).

To assess whether selective attrition might have contributed to a low rate of ADHD in adulthood, we examined whether the probands who were not asked about adult ADHD symptoms had a higher rate of ADHD in adolescence than did the comparison subjects. No significant differences between probands and comparison subjects were found, regardless of whether the diagnoses at the adolescent follow-up were based on self-reports (17% versus 22%) (χ2=0.13, df=1, p=0.72), informant interviews with parents (33% versus 44%) (χ2=0.48, df=1, p=0.49), or either (38% versus 46%) (χ2=0.29, df=1, p=0.59).

The findings from the present, previous (

13), and Weiss et al. (

12) studies, the only prospective studies of ADHD children followed into adulthood of which we are aware, suggest that there is no “true” or universal rate of adult ADHD in subjects who were clinically diagnosed as having ADHD in childhood. Instead, persistence of the syndrome into adulthood likely depends on a multitude of interacting factors. Indeed, formulating a differential diagnosis of adult ADHD requires specialized knowledge and skillful interviewing since the symptoms of ADHD overlap with those of other disorders, and adult comorbid disorders are not uncommon. Furthermore, the prevalence of adult ADHD is likely to vary with the particular criteria set used, partly because the criteria in official nomenclatures, such as DSM-IV, were written for children, not adults. In addition, reports on treating ADHD in adults necessarily have relied on retrospective diagnoses of childhood ADHD, many of which were based exclusively on patient recollections. To address some of these issues, we turn to ongoing prospective, controlled studies of ADHD children who are followed into adulthood (e.g., those described in references 6 and 24).

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

In this study there was no evidence that ADHD probands were at greater risk for having a current mood or anxiety disorder in adulthood (

table 1). Similarly, the

lifetime rates in the probands and comparison subjects of mood disorders (24% versus 23%) (χ

2=0.00, df=1, p=1.00) and anxiety disorders (5% versus 9%) (χ

2=0.79, df=1, p=0.37) did not differ significantly. These findings are consistent with those from our previous adult follow-up (

13), our two adolescent follow-ups (

4,

5), and the Canadian study (

12).

We considered whether our interviewers had underdiagnosed mood and anxiety disorders in the present study. To assess this possibility, we compared the rates of these disorders in our comparison subjects to the rates reported in two major epidemiological studies. In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey (

23), the 1-month prevalence rates for men aged 18–44 years from five U.S. sites were as follows: DSM-III mood disorders, 3.4%–4.5% (versus 4% in the current study); DSM-III anxiety disorders, 4.7%–4.9% (versus 7% in the current study). For males aged 15–34 years in the National Comorbidity Survey (

25), the 1-month prevalence rates for DSM-III-R simple phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia (the most common anxiety disorders) were 0.6%–6.6% (versus 5% for these disorders in the present study). Although the results of these studies and ours are not directly comparable because of numerous procedural differences, they suggest that we did not tend to underestimate mood or anxiety disorders. It is also important to reiterate that the interviewers were blind to group membership.

Although the results of follow-up studies are consistent, thus far, in their failure to find a relationship between ADHD and mood and anxiety disorders, the results of family studies are more difficult to interpret. Regarding ADHD and mood disorders, some family studies support an association (

26,

27) and others do not (28, 29, and unpublished 1990 study of R.G. Klein and S. Mannuzza). Similarly, some studies have shown higher than normal rates of ADHD among children of depressed parents (

30), whereas others have not (

31). Regarding ADHD and anxiety disorders, some studies support an association (

27,

32) and other studies do not (33 and unpublished study of Klein and Mannuzza).

The inconsistencies between the results of follow-up and family studies render clear-cut conclusions difficult.

ADHD or Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood?

DSM-II defines hyperkinetic reaction of childhood as “characterized by overactivity, restlessness, distractibility, and short attention span” (p. 50). This description approximates what was later termed “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” (DSM-III-R and DSM-IV). We are confident that the children in the present study would have been diagnosed as having ADHD. The following childhood features support this assumption.

1. Hyperactivity. All children were required to be cross-situationally hyperactive, i.e., judged hyperactive by teachers

and parents or clinic staff, and each child was required to have a rating of at least 1.8 on the hyperactivity factor of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (

16). The standard for identifying ADHD in the classroom is a factor score of 1.5. The probands in the present study had a mean factor score of 2.4 (SD=0.5).

2. Inattention. The scores on the Conners Teacher Rating Scale range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). The children in the current study obtained the following scores on the three inattention items: “inattentive, distractible,” mean=2.6 (SD=0.6); “short attention span,” mean=2.5 (SD=0.7); “daydreams,” mean=1.6 (SD=0.8). Of the 104 probands in the present study, 80 (77%) were each given a rating of 3 (very much) by a teacher on at least one of these items.

3. Impulsivity. The mean score on the “excitable, impulsive” item of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale was 2.6 (SD=0.7). Sixty-three percent of the probands in the present study were given ratings of 3 (very much).

4. Classroom observations. Perhaps the most compelling evidence that the present cohort represented ADHD in childhood comes from classroom observational data. About 90% of the present probands were part of a study in which each index child was paired with a classmate reported as presenting “average behavior” by his teacher (

34). Each child was rated on numerous behaviors by blind raters at least three times for 16 minutes each. Three measures are relevant to the diagnosis of ADHD: “out of chair,” “off task,” which reflects a failure to remain focused, and “interference,” a measure of impulsivity. Highly significant group differences were obtained; the probands had worse scores, and these measures, when combined in dyads, did not identify a single “normal” child as hyperactive (

34).

Subjects Lost to Follow-Up

Thirteen of the 19 probands who were lost to adult follow-up had participated in the adolescent follow-up (

5). We compared the adolescent diagnoses of these 13 subjects to those of the 81 probands evaluated in both adolescence and adulthood. No significant differences were found: antisocial personality, 38% versus 31% (χ

2=0.05, df=1, p=0.82); substance use disorder, 15% versus 14% (χ

2=0.00, df=1, p=1.00); attention deficit disorder, 46% versus 42% (χ

2=0.00, df=1, p=1.00); any DSM-III disorder, 62% versus 51% (χ

2=0.19, df=1, p=0.66).

Only five of the 78 comparison subjects were not evaluated during the present adult follow-up. Of these, one was diagnosed at adolescent follow-up (

5) as having DSM-III antisocial personality and dysthymia, one as having alcohol abuse, and three as having no ongoing disorder. The number of missing cases is too small to allow meaningful comparison.

The preceding findings suggest that attrition did not account for the differences in outcome.

Limitations

In the present study we examined the adult outcome of predominantly middle-class, white, cross-situationally hyperactive boys of average intelligence who were referred to a child psychiatric research clinic. It is not known to what extent the results can apply to different groups. For example, compared to randomly selected subjects from the community, clinic-referred patients are likely to be more severely ill.

We studied the outcome of children with relatively “pure” ADHD. Our study group is not representative of ADHD children as a whole since both epidemiologic and clinical studies show that 30%–50% of these children have comorbid conduct disorders (

35).

We view the absence of conduct disorder in the childhood of the ADHD children we followed up as a positive feature. At this time, it is critical to examine the natural history of ADHD independently of the well-known adverse consequences of conduct disorder since 50%–70% of children with ADHD do not have conduct disorder. In this context, it is relevant to note that even in the case of conduct disorder, which is viewed generally as a chronic disorder, the majority of affected children do not retain the disorder into adulthood. Therefore, it should not be surprising to find that most cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood. Perhaps a more salient question is, Why do antisocial personality disorder and nonalcohol substance use disorder appear in a substantial proportion of ADHD children grown up? We will be assessing childhood and adolescent predictors of the adult outcome of the combined cohorts (N=207) in a separate paper.