Social phobia is a commonly occurring anxiety disorder (

1–

5) often associated with serious role impairment (

3,

4,

6,

7). Distinct symptom profiles have been found in clinical samples of some patients suffering exclusively from performance fears (e.g., speaking in public) and others with a broader array of fears that include both performance and interactional fears (e.g., meeting new people) (

8–

10). The latter disorder is referred to as generalized social phobia (DSM-IV).

Generalized social phobia has been observed to be more severe and disabling than other social phobias (

11). Therefore, in planning public health responses to the findings that social phobia affects more than one out of eight people in the population on a lifetime basis (

3) and as many as 8% in a year (

1,

2), it would be useful to know the proportion who have broad-based and seriously impairing social fears versus less extensive or impairing fears. This was the purpose of the present investigation. In this report we show that two empirically derived subtypes of social phobia can be found in a large general population survey that distinguish people with exclusively speaking fears from other people with social phobia. While it has previously been noted that many persons in the community suffer from public speaking fears that can be considered a form of social phobia (

12), to our knowledge no previous epidemiologic study has examined this or other social phobia subtypes in the general population. We present data that compare these subtypes on family history, comorbidity, impairment, and sociodemographic correlates.

RESULTS

Lifetime Prevalences of Social Fears and Social Phobia

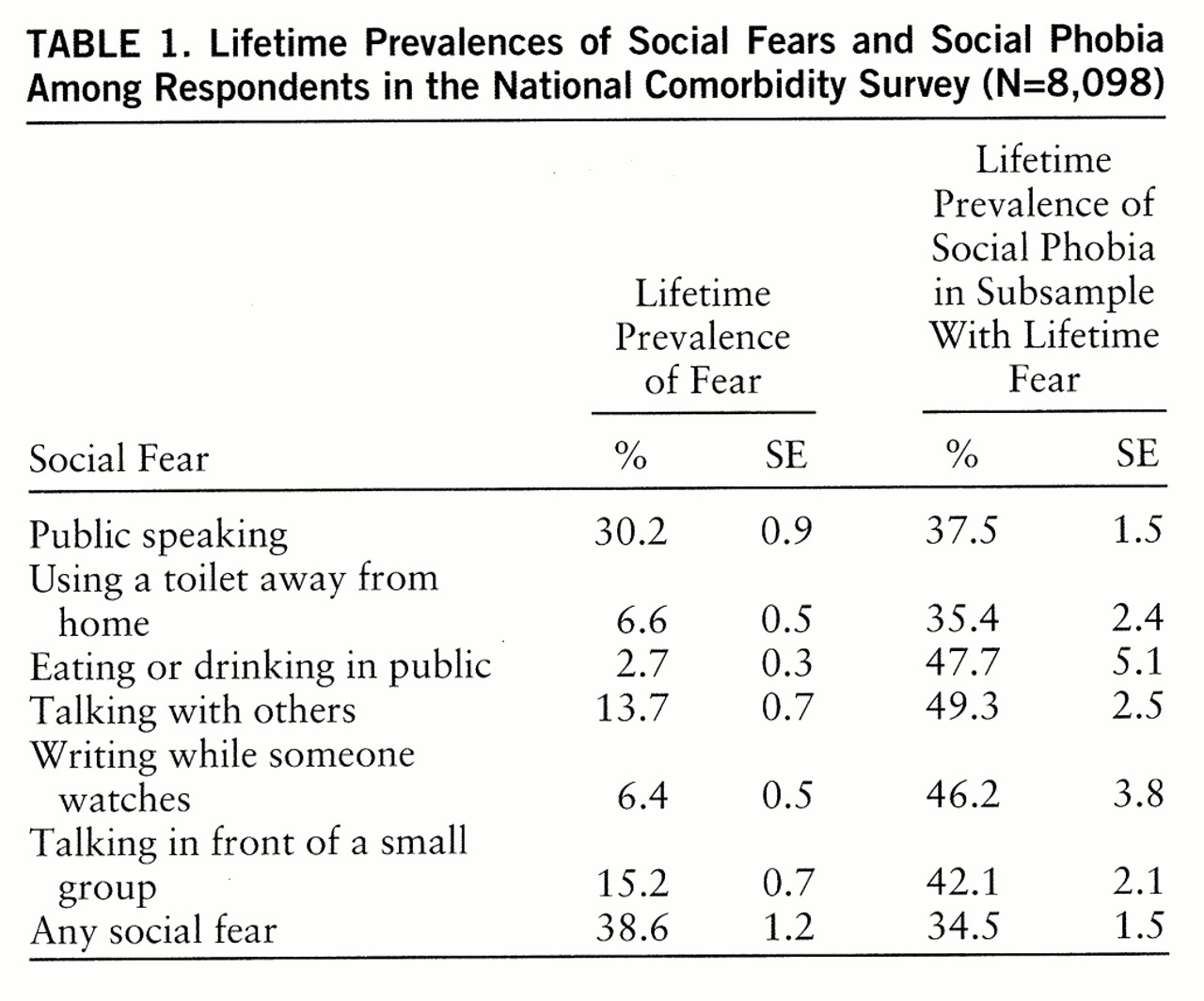

As shown in

table 1, the lifetime prevalences of the six social fears in the total sample ranged from 2.7% for fear of eating or drinking in public to 30.2% for fear of speaking in public. The lifetime prevalence of at least one fear was 38.6%. The speaking fears were the most common. The conditional probabilities of social phobia given a particular social fear (i.e., the proportion of people with a given fear who met the criteria for social phobia) had a much narrower range, from 35.4% for fear of using a toilet away from home to 49.3% for fear of talking with others, and they averaged 34.5% across all fears.

Latent Class Analysis of Lifetime Social Fears

Latent class analysis models for the six lifetime social fears were fit for between one and four classes. A three-class model was found to provide the best fit, as indicated by the improvement over a two-class model (χ2=314.2, df=7, p<0.001) and the failure of a four-class model to improve over the three-class model (χ2=0.01, df=7, p=1.00). Class 1 was characterized by low endorsement probabilities. Class 2 was characterized by a 93% probability of fear of speaking in public, a probability over 50% of fear of speaking in front of a small group, and a 32% probability of fear of talking with others. Class 3 was characterized by comparatively high probabilities of all six fears.

Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalences of Social Fear and Phobia Subtypes

On the basis of the results of the latent class analysis, the respondents with social fears were divided into two broad groups, those with pure speaking fears and those who endorsed at least one other social fear (with or without a speaking fear). Because of the much higher prevalence of public speaking fear than other social fears, the group with pure speaking fear was further divided into those with public speaking fear only and those with more extensive speaking fears. The group that endorsed other social fears, in comparison, was further divided into those with one, two, and three or more social fears in order to distinguish the effect of number from the effect of type of social fears.

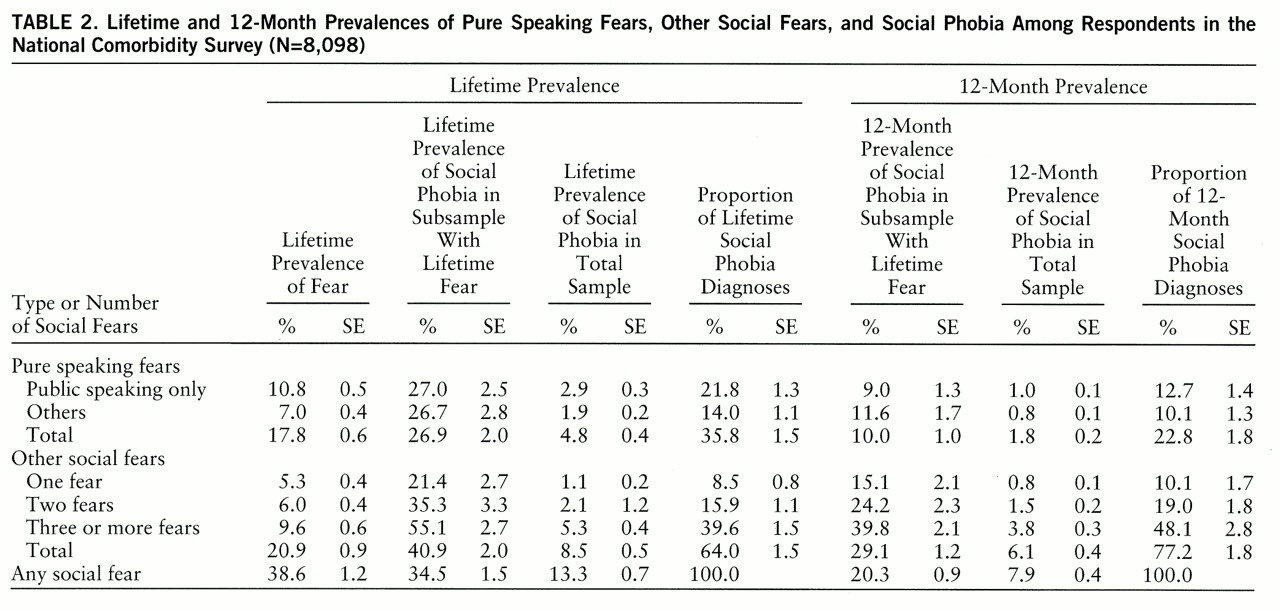

The lifetime and 12-month prevalences of social fears and social phobia in these various subgroups are reported in

table 2. Similar proportions of the total sample reported one or more lifetime pure speaking fears (17.8%) and other social fears (20.9%). Within the subsample with pure speaking fears, over one-half reported that their only social fear was public speaking. Within the group with other social fears, about one-fourth reported only one of the fears, while close to one-half reported three or more of the six social fears.

As shown in the third data column, a significantly lower proportion of those with pure speaking fears (26.9% of 1,441) than other social fears (40.9% of 1,691) (z=4.9, p<0.001) met the criteria for lifetime social phobia. As a result, even though the lifetime prevalences of pure speaking fears and other social fears were roughly equal, in the total sample the lifetime prevalence of social phobia with nonspeaking fears (8.5%) was much higher than the lifetime prevalence of social phobia with pure speaking fears (4.8%) (z=5.8, p<0.001). There was an even larger difference between the conditional prevalences of 12-month social phobia in the subsamples of people with lifetime pure speaking fears (10.0% of 388) and those with other lifetime social fears (29.1% of 692) (z=12.3, p<0.001), suggesting that the former are less persistent than the latter. There was a significant association between the number of lifetime fears and the probability of lifetime phobia within the subsample having nonspeaking fears, from a low of 21.4% among the 429 respondents with only one fear to a high of 55.1% among the 777 with three or more fears (z=8.8, p<0.001). There was no significant difference, however, between the probability of lifetime social phobia in the subsample of respondents with pure fear of public speaking (27.0% of 875) and the probability for those with other pure speaking fears (26.7% of 567) (z=0.08, p=0.99).

Age at Onset and Time to Offset

Kaplan-Meier cumulative curves for age at onset based on retrospective reports were computed separately for social phobia with pure speaking fears and for subgroups of other social phobias defined on the basis of number and type of fears. No evidence was found for meaningful differences in the age-at-onset distributions of these subsamples.

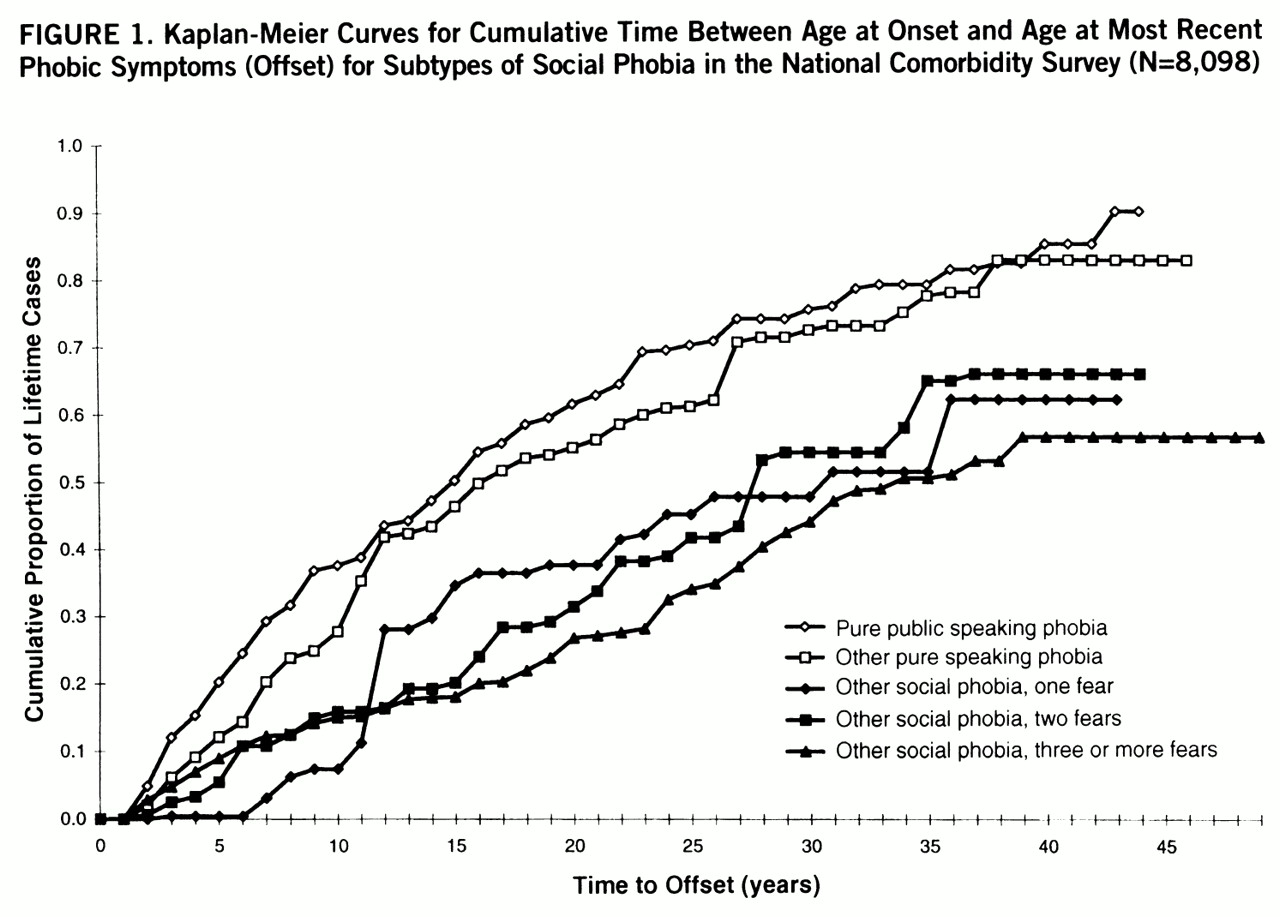

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to offset were also computed for the same subsamples. Time to offset was the number of years between retrospectively reported age at onset and age at most recent phobic symptoms. As shown in

figure 1, time to offset was significantly shorter for social phobia with pure speaking fears than for social phobia with other social fears (χ

2=86.2, df=1, p<0.001). There was no significant difference in time to offset, in comparison, among the subsamples defined by number of fears for either the respondents with social phobia and pure speaking fears (χ

2=3.0, df=2, p=0.08) or those with social phobia with other social fears (χ

2=3.0, df=2, p=0.22).

Parental History of Psychopathology

There were consistently positive associations between parental history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, substance dependence, and antisocial personality disorder and the respondents' lifetime social phobia. However, we found a statistically significant difference between social phobia with pure speaking fears and other social phobia in only one of the measures of parental psychopathology, maternal generalized anxiety disorder (χ2=8.2, df=2, p<0.001); the prevalence was lower among those with pure speaking fears than among those with other social phobias.

Comorbidity

A previous report from the National Comorbidity Survey documented substantial comorbidity of lifetime social phobia and other lifetime DSM-III-R disorders assessed in the survey (

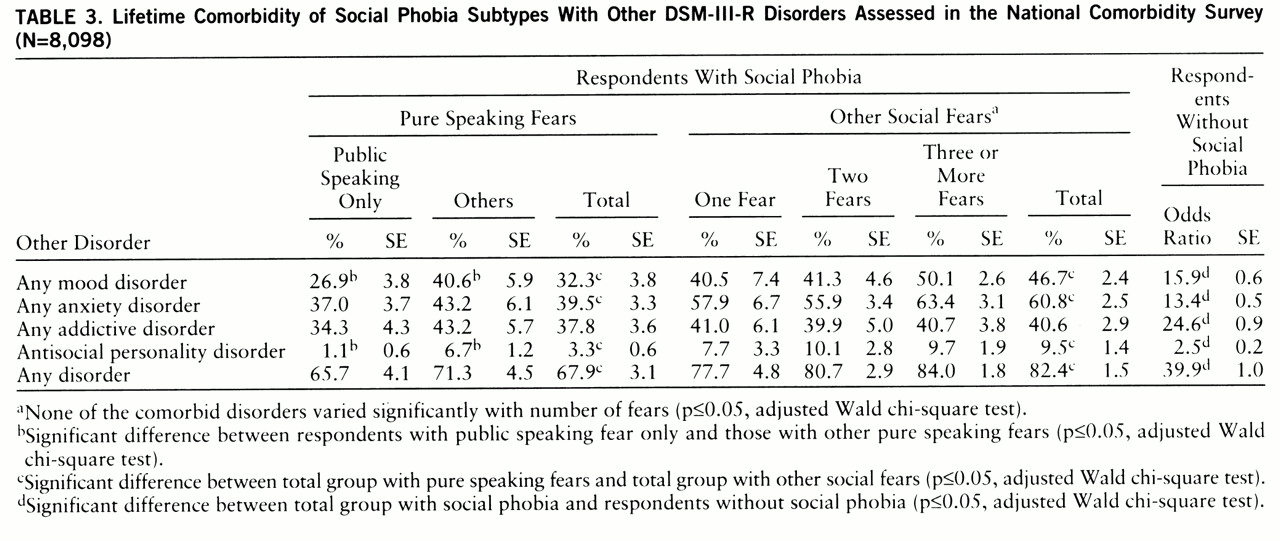

3). The results in

table 3 show that there was also considerable variation in comorbidity across subtypes of social phobia. Histories of mood disorder, anxiety disorder, and antisocial personality disorder were all significantly more common among respondents who had social phobia with at least one nonspeaking fear than among those with social phobia and pure speaking fears. Among the respondents with social phobia and comorbid disorders, furthermore, those with pure speaking fears were significantly more likely than those with other social fears to report that social phobia was their earliest lifetime disorder (73.4% of 263 versus 59.4% of 570) (z=2.3, p=0.03). For the respondents with social phobia, there was less comorbidity with mood disorder and antisocial personality disorder among those with public speaking fears only than among those with other pure speaking fears. However, comorbidity was not associated with the number of social fears among those with social fears beyond speaking.

Impairment

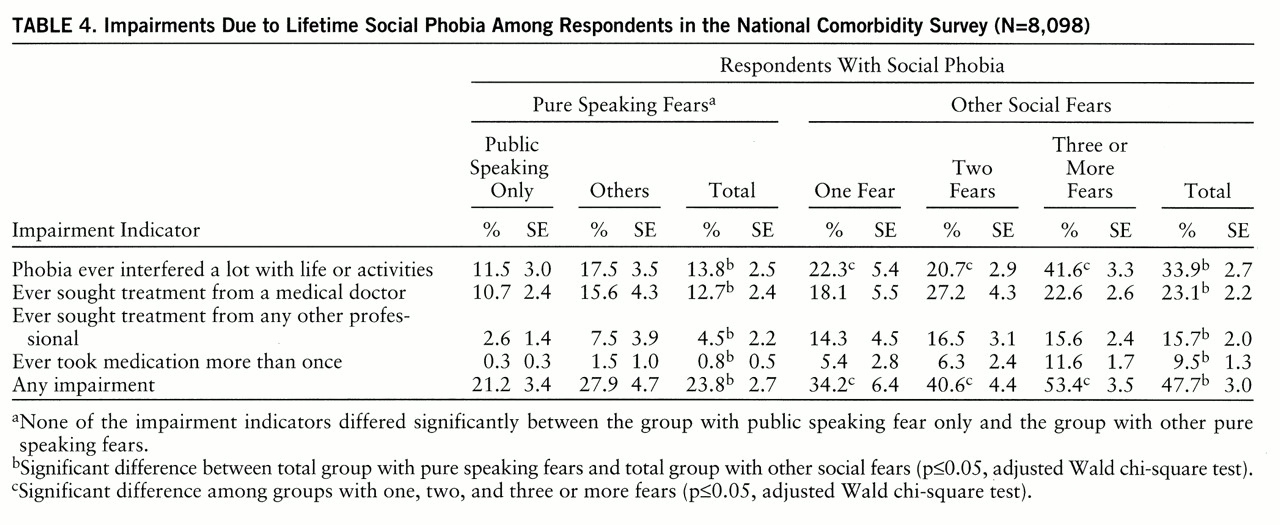

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview includes four indicators of impairment in each diagnostic section: whether the disorder ever interfered a lot with the respondent's life or activities, whether the respondent ever sought treatment from a medical doctor, whether the respondent ever sought treatment from any other professional (e.g., social worker or clergy), and whether the respondent ever took medications more than once for the disorder. Of the respondents with lifetime social phobia, 39.1% endorsed at least one of these impairment statements. As shown in

table 4, the percentage of endorsement was approximately twice as high for respondents with nonspeaking fears (47.7% of 388) as for those with pure speaking fears (23.8% of 692) (z=5.9, p<0.001). Within the subsample of respondents with social phobia having at least one nonspeaking fear, furthermore, the endorsement percentage was monotonically related to number of fears: 34.2% of the 92 with one fear, 40.6% of the 171 with two fears, and 53.4% of the 428 with three or more fears (χ

2=15.6, df=2, p<0.001).

Sociodemographic Correlates

A previous report on the National Comorbidity Survey (

3) documented several sociodemographic correlates of lifetime social phobia, the most powerful being low income, low education, and female gender. Disaggregated analyses showed no specification by subtype for the gender effect. However, there were significant findings for income and education, both of which were significantly inversely related to social phobia with nonspeaking fears (income: χ

2=36.2, df=3, p<0.001; education: χ

2=88.3, df=3, p<0.001). Social phobia with pure speaking fears, in comparison, was not significantly related to income (χ

2=2.6, df=3, p=0.45) and was nonmonotonically related to education; i.e., there were high rates among both high school graduates and those with some college education and low rates both among those with less than a high school education and among college graduates (χ

2=29.2, df=3, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The finding of two social phobia subtypes is superficially consistent with theoretical speculation (

11,

12,

31) and clinical observations that patients with social phobia can be divided into those with predominantly performance-type fears and those who also have a broader range of interactional fears (

9,

32,

33). However, there are two important differences between the subtypes found in the National Comorbidity Survey and those found in clinical studies. First, persons with social phobia with pure speaking fears are rare in clinical samples because they have a low rate of service use. As a result, clinical studies have failed to identify the pure-speaking-fear subtype found here. Second, the pure-performance-fear subtype in clinical studies is usually characterized by a larger set of performance fears, such as fear of writing in public and fear of eating in public, in addition to speaking fears, while generalized social phobia is characterized by a combination of performance fears and interactional fears, such as fears of dating, of attending social gatherings, and of speaking with strangers.

We did not find a distinction between the latter two subtypes (broadly defined performance fear versus generalized fear) in the National Comorbidity Survey. Our failure to find this distinction is probably due to the fact that only one of the six questions in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview asked about an interactional fear (fear of talking to people because you might have nothing to say or might sound foolish). This highlights an important limitation in the National Comorbidity Survey for purposes of the current analysis: the survey assessed only six social fears. A much larger set of social fears, including a wider range of performance fears plus interactional fears, is needed in future epidemiologic studies to carry out more fine-grained subtyping of social phobia.

Despite this limitation, it is worth noting that in the National Comorbidity Survey the subtype involving at least one nonspeaking fear was found to be more chronic, comorbid, and impairing than the pure-speaking-fear subtype and that this was especially true for respondents with three or more social fears. The vast majority of survey respondents with this subtype endorsed the statement about the one interactional fear included in the survey. The fact that these people reported the most impairment is consistent with the clinical observation that patients in treatment for social phobia who have fears of most social situations are more impaired than those who have fewer social fears (

34). This finding presumably reflects the fact that situations that require public speaking can be avoided by most people with less impairment than situations that require other types of social performance or social interaction.

Our finding that socioeconomic status is inversely related to social phobia with nonspeaking fears could be due either to social causation (socioeconomic success protecting against social phobia), social selection (early-onset social phobia interfering with socioeconomic success), or some combination of these processes. The finding that social phobia with pure speaking fears is more prevalent among those with high school or some college education than either college graduates or people with less than a high school education is most plausibly interpreted as a mixture of processes that include lack of exposure to the phobic stimulus among people with little education (i.e., a low chance of the fear of public speaking ever being activated among people with low education because it is rare for them to be called on to speak in public) and social selection at higher levels of education (i.e., speaking phobia might interfere with subsequent educational attainment among high school graduates).

It is interesting to consider whether the apparently lower degree of impairment among respondents with social phobia with pure speaking fears than among those with other social phobia is simply a matter of number rather than type of fears. There is no way to answer this question definitely in the National Comorbidity Survey because the set of six social fear questions is too brief to permit confidence that people classified as having only one social fear would not have reported others if a longer list had been presented. Nonetheless, it is informative to compare the 35.8% of respondents with social phobia in the survey who were classified as have pure speaking fears with the 8.5% who had only one other fear among the six assessed. A comparison of these two subgroups showed that respondents with pure-speaking-fear social phobia had a weaker family history of the disorders considered here, less comorbidity, and less impairment than the respondents with social phobia who had only one nonspeaking social fear each.

This last result might mean that pure-speaking-fear social phobia is a different type of social phobia than social phobia characterized by nonspeaking fears. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that social phobia with pure speaking fear is not real social phobia. As other studies have shown (

11), some persons with pure-speaking-fear social phobia experience considerable impairment. Furthermore, it is possible that some of these persons experience more subtle forms of impairment than the measures used in the survey were able to detect. As already noted, it would be useful for future epidemiologic surveys to assess a broader range of social situations, both performance and interactional, than the six in the National Comorbidity Survey in order to assess this possibility and provide a rigorous definition of the DSM-IV requirement that generalized social phobia include fears of “most social situations.” Despite this limitation, though, we can draw two useful conclusions from the results reported here. First, a substantial proportion of persons with social phobia in the general population have pure speaking fears, although a more in-depth assessment might show that fears of other social situations are also involved in some cases, while other people with social phobia generally have a greater number of fears that usually involve both performance and interaction. It is not clear from the results reported here whether these two represent distinct subtypes or, rather, different severity thresholds on a single dimension of extensiveness of social fears. It is clear, though, that speaking fears are much more prevalent than the other social fears considered here and that a substantial proportion of people with social phobia meet the criteria exclusively because of speaking fears.

Second, social phobia that involves more extensive fears is more persistent, is associated with more impairment, and is more frequently present with other DSM-III-R disorders than the subtype with pure speaking fears. For these reasons, social phobia involving multiple fears that are not exclusively fears of speaking should be the focus of the most intensive public health interest until more fine-grained subtyping can be done.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The National Comorbidity Survey is a collaborative epidemiologic investigation of the prevalences, causes, and consequences of psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in the United States supported by NIMH (MH-46376, MH-49098, MH-52861) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (through a supplement to MH-46376) and the W.T. Grant Foundation (90135190), Ronald C. Kessler, principal investigator. Preparation for this report was also supported by an NIMH Research Scientist Award to Dr. Kessler (MH-00507). Collaborating National Comorbidity Survey sites (and investigators) are as follows: Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room), Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz), Harvard Medical School (Richard Frank, Ronald Kessler), Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaton, Philip Leaf), Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry Clinical Institute (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen), Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler), University of Miami (R. Jay Turner), University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston, Roderick Little), New York University (Patrick Shrout), State University of New York at Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet), and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cott~ler, Andrew Heath). A complete list of all National Comorbidity Survey publications along with abstracts, study documentation, interview schedules, and the raw National Comorbidity Survey public use data files can be obtained directly from the National Comorbidity Survey home page by using the URL http://www.umich.edu/~ncsum/ on the World Wide Web.