Despite substantial advances in the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder (

1), a number of longitudinal outcome studies indicate that the course of this illness remains unfavorable for many patients (

2–

12). Among these studies, 1-year relapse rates have ranged from 37% (

10) to 44% (

5), and enduring psychosocial impairment despite symptomatic recovery has been described in a substantial number of patients (

6,

13).

Relatively few studies have attempted to identify predictors of outcome in patients with bipolar disorder. Clinical characteristics identified as potential predictors of poor outcome include older age at onset (

14), male sex (

2,

15,

16), race (

12), poor occupational status (

2,

10), low socioeconomic status (

4,

5), number of previous episodes (

2,

10,

15,

17), number of previous hospitalizations (

4,

5), duration of illness (

18), mixed episodes (

7,

19–

24), symptoms of depression during manic episodes (

2,

10,

14,

20,

21), interepisode symptoms (

2,

10,

25–

27), psychosis (

2,

10,

28,

29), mood-incongruent symptoms (

30–

32), and concurrent substance-related disorders (

2,

5,

8,

10). However, not all studies have found an association between outcome and some of these putative predictors, including male sex (

28), number of previous episodes (

9), number of previous hospitalizations (

9), and psychosis (

4,

9).

There are several methodologic differences among these outcome studies that may explain their divergent findings but limit their interpretation. First, although all were naturalistic in design, several studies (

5,

18,

25) examined patients treated with a specific pharmacological agent, e.g., lithium, and thus are not representative of the outcome of patients treated with other contemporary medications. Second, few studies (

10,

25,

31) attempted systemically to assess the degree to which patients adhered to pharmacotherapy, thus leaving unexamined the role of noncompliance on outcome. Third, relatively few studies used modern diagnostic criteria (

2–

6,

9,

10,

30,

31), structured diagnostic interviews (

2–

6,

9,

29–

31), or prospective quantitative assessments of syndromic, symptomatic, and functional outcome (

2–

6,

9,

30,

31). Fourth, some studies followed only patients identified at hospitalization (

2,

4,

15,

31,

32), some followed only outpatients (

5,

10,

11,

28,

29), and some followed patients from both referral sources (

6–

8,

19). Fifth, a number of studies excluded patients with rapid cycling and mixed episodes (

2,

3,

30) or patients with multiple episodes (

2,

3,

12,

30,

32). Finally, since many of these potential predictors of outcome are highly correlated, analyses should control for potential interactions, but this has been done in only a few studies (

2–

4,

9,

10,

12,

30). Multivariate analyses may clarify such interactions. For example, a multivariate approach might identify whether substance use disorders contribute to poor outcome directly by influencing symptoms or indirectly by contributing to treatment noncompliance (

12).

In previous studies (

12,

33), our group refined operational criteria based on the recommendations of Frank et al. (

34) to differentiate symptomatic, syndromic, and functional recovery for application to patients with bipolar disorder. Syndromic recovery is a categorical measure that refers to the resolution of a specific constellation of symptoms to the point that diagnostic criteria are no longer met, whereas symptomatic recovery is a dimensional measure that refers to improvement in the magnitude of symptoms. This differentiation permits the examination of psychopathology that persists despite symptomatic improvement to the point that patients no longer meet diagnostic criteria for an episode. Functional recovery refers to the return to previous levels of work and psychosocial function. These distinctions are important because separating these aspects of recovery may help clarify factors that differentially contribute to the recovery process (

10,

12,

13,

33).

With these methodologic considerations in mind, we report the results of a prospective outcome study of 134 patients with bipolar I disorder followed for 12 months after hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. In this study, we asked the following questions: 1) Does the presence of mixed states predict poorer outcome than the presence of pure mania? 2) Do comorbid substance use disorders and treatment noncompliance independently contribute to poor outcome? 3) Are there different predictors of syndromic, symptomatic, and functional recovery?

METHOD

Subjects

Patients were recruited from consecutive admissions to the University of Cincinnati Hospital inpatient psychiatric units from October 1992 through May 1995. The University of Cincinnati Hospital serves as both a regional tertiary referral center and a primary care provider for the Cincinnati metropolitan area. In addition, the psychiatry department is closely affiliated with the community mental health system and administers the county indigent acute care unit, which is located at the hospital.

Patients were included in this study if they 1) were 15–45 years of age; 2) met criteria for DSM-III-R bipolar disorder, manic or mixed; 3) could communicate in English; 4) resided within the Cincinnati metropolitan area; and 5) provided written informed consent after the study procedures had been fully explained. Patients were excluded if 1) manic or mixed symptoms resulted entirely from acute intoxication or withdrawal from drugs or alcohol, determined by resolution of symptoms within the expected period of acute withdrawal and intoxication for the abused substance as described elsewhere (

12,

35,

36), or 2) manic or mixed symptoms resulted entirely from a medical illness, determined by medical evaluation.

Recruitment involved daily review of the medical records of all new psychiatric admissions to identify potential study patients. A total of 199 potential subjects were evaluated; 141 (71%) of these patients met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of this latter group, 134 patients (95%) provided written informed consent and are the subjects of this report. Seven patients refused to participate in this study or left the hospital too quickly to be recruited. These patients did not differ significantly from the 134 subjects included in the study in age, education, socioeconomic status, diagnosis, race, or sex distribution.

Demographic Variables and Diagnostic Assessment

Age, sex, race, and social class based on the total years of education and highest level of employment in the previous year, as in the two-factor index of Hollingshead (

37), were recorded. Axis I psychiatric diagnoses were determined by psychiatrists (P.E.K., S.L.M., S.M.S., S.A.W.) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P) (

38,

39). Interrater reliability was good for both principal (kappa=0.94) and comorbid (kappa>0.90) diagnoses (

35,

36,

40). When completing the SCID-P, the psychiatrists obtained information from the patient interview, medical records, treating clinicians, and family members. Diagnostic interviews were performed at the index hospitalization and at the 12-month follow-up visit.

Symptom Assessment

Symptom ratings were performed within 3 days of admission by trained research assistants using the Young Mania Rating Scale (

41), the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

42), and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (

43). Raters had established interrater reliability from joint ratings of more than 100 patients with an experienced psychiatric research nurse. Interrater reliabilities, calculated by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), were ICC=0.94 for the Hamilton depression scale total score, ICC=0.71 for the Young Mania Rating Scale total score, and ICC=0.72–0.93 for the SAPS global score (

12).

Premorbid Assessment

Premorbid function was assessed by using the nine general items from the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (

44), which evaluates a person's educational achievement, ability to maintain independent living and employment, ability to function outside the nuclear family and form peer relationships, and level of interest in life pursuits. The Premorbid Adjustment Scale consists of nine items, each rated on a 7-point scale of 0–6. The total score is then calculated by summing all nine items and dividing by the maximum score possible (9×6=54), yielding a composite score ranging between 0.0 and 1.0. A higher score indicates poorer premorbid function. Premorbid Adjustment Scale ratings were performed by research assistants; their interrater reliability was ICC=0.87.

Outcome Assessments

Patients were scheduled for follow-up evaluations at 2, 6, and 12 months after hospital discharge, although the actual times patients attended these visits were mean=2.6 months (SD=1.1), mean=6.4 months (SD=0.9), and mean=13.6 months (SD=2.7), respectively. The rationale for these intervals is based on previous work (

2,

33,

45–

47). To assess recovery at each visit, the interviewers concentrated on change points that occurred during the interval, i.e., times when symptoms or function improved or worsened, corresponding to the methodology of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (

45). Syndromic, symptomatic, and functional recovery were defined a priori as follows (

12):

Syndromic recovery. Eight contiguous weeks (

34) during which the patient no longer met criteria for a manic, mixed, or depressive syndrome. Recovery from each of these syndromes was based on DSM-III-R criteria and was operationalized as follows: manic syndrome—no longer meeting the A or B criterion for a manic episode; depressive syndrome—no longer meeting the A criterion for a major depressive episode; mixed syndrome—no longer meeting the A or B criterion for a manic episode and the A criterion for a major depressive episode.

Symptomatic recovery. Eight contiguous weeks (

34) during which the patient experienced minimal to no psychiatric symptoms, operationalized as follows: Young Mania Rating Scale total score of 5 or less, Hamilton depression scale total score of 10 or less, and SAPS global item score of 2 or less (mild) (

48).

Functional recovery. Return to premorbid levels of function for at least 8 contiguous weeks (

34). To assess functional recovery, seven of the nine general items from the Premorbid Adjustment Scale were evaluated at each follow-up visit for the interval period (excluding ratings of education and abruptness in the change in work associated with the index episode, since these scores could not change). To meet criteria for functional recovery, subjects had to receive Premorbid Adjustment Scale general item interval scores less than or equal to the premorbid rating on five of the seven items and have no interval item score more than 2 points higher than the corresponding premorbid item score.

Medications and Treatment Compliance

Psychiatric medications prescribed at discharge from the index hospitalization were categorized as follows: mood stabilizer (lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine) alone; antipsychotic alone; antidepressant alone; mood stabilizer plus antipsychotic; mood stabilizer plus antidepressant; mood stabilizer plus antipsychotic plus antidepressant; and antidepressant plus antipsychotic. Treatment compliance (

49) was defined as full compliance, partial noncompliance, and total noncompliance. In full compliance, there was evidence from the patient, clinician, and significant others that the patient's medication regimen was taken in the manner prescribed by the physician (75%–100% adherence to the prescribed regimen). In partial noncompliance, there was evidence that some medications were not taken consistently or that most or all medications were taken intermittently or at doses lower than prescribed (25%–75% adherence to the prescribed regimen). In total noncompliance, there was evidence of complete discontinuation of all psychotropic medications (0%–25% adherence to the prescribed regimen).

To improve the validity of the outcome measures, “best-estimate” meetings were held following the completion of the 12-month visits (

12,

50). The best-estimate procedure involved reviewing the symptoms and diagnostic ratings from 1) the index hospitalization, 2) the follow-up assessments at 2, 6, and 12 months, 3) the 12-month diagnostic assessment (SCID-P), and 4) any available clinical records. Information from these multiple sources was compared and, in cases of disagreement, a consensus was obtained among the research team members for the outcome and interval measures. These best-estimate determinations were used for all analyses. To evaluate the reliability of this process, we repeated best-estimate determinations for 20 patients more than 1 month after they had been completed for all subjects; the agreement for both syndromic and symptomatic recovery was 100% (all 20 patients), and the agreement for functional recovery was 95% (19 patients).

The methodology for this study (e.g., the 8-week duration for recovery and the symptom cutoff scores) was developed on the basis of previous studies and expert panel recommendations (

2–

13,

30,

33,

51). The specific outcome of the patients included in the present study who were experiencing their first episode of affective psychosis has been described elsewhere (

12).

Risk Factors

For Cox regression analysis, the number of independent variables should not exceed 10% of the total number of subjects (

52). Thus, for the analysis of the 106 subjects who completed the 12-month outcome study, the total number of independent variables was limited to 10. However, more variables were considered as potential risk factors for outcome measures, including age, sex, race, social class, age at onset of illness, duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, concurrent substance use disorder, affective state (manic versus mixed), depressive symptoms (Hamilton depression scale total scores), manic symptoms (Young Mania Rating Scale total scores), psychotic symptoms (SAPS total scores), the presence of mood-incongruent psychosis, premorbid adjustment, treatment compliance, and categories of medication treatment. Additionally, a number of interactions were examined, including race and sex, sex and substance use disorder, race and substance use disorder, psychosis and mood-incongruent symptoms, and category of treatment and compliance.

To decrease the number of variables for the final model, we examined all of these potential predictors through a series of steps. First, variables exhibiting high levels of intercorrelation were combined (e.g., because alcohol and substance abuse exhibited a correlation of phi=0.41, df=1, p<0.001, they were combined as substance use disorder) (

53). Next, multicollinearity was examined by means of factor analytic techniques, although in this data set, after bivariate correlation was controlled for, multicollinearity was minimal. Third, we evaluated stepwise logistic regression models for the outcome predictors using liberal entry criteria for the variables (alpha=0.3). From these analyses and in consideration of the findings of previous studies (

2,

4–

6,

8,

10,

12,

14–

32), we identified 10 variables for inclusion in the final model. These were sex, race, social class, duration of illness, concurrent substance use disorders, affective state (manic versus mixed episode), depressive symptoms (Hamilton depression scale total scores), manic symptoms (Young Mania Rating Scale total scores), presence of psychosis (SAPS scores), and treatment compliance. None of the interaction terms was associated with outcome in these preliminary analyses; therefore, all were excluded from the final model.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed by using the statistical software SAS (

54). To identify significant predictors of dichotomous outcome variables (e.g., the presence or absence of syndromic recovery during the 12-month follow-up period), logistic regression models were used. For these analyses, only the subjects who completed the 12-month follow-up (N=106) were used. All 10 hypothesized predictors of outcome were included in these models. For dichotomous variables, adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Survival curves based on the Kaplan-Meier method (

55) were used to estimate the probability of recovery during the 12-month interval. For these curves, recovery was scored as present at the time it began. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to assess the effects of the 10 risk factors on the time to outcome events. Since Cox analysis permits right-censored data, all subjects who completed at least one follow-up visit (N=117) were included. All covariables were examined to ensure that they met the proportional hazards assumption for these regression models (

52), and none exhibited significant deviance from this assumption. Adjusted hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were computed for each risk factor with adjustment for all the remaining variables. Other statistical comparisons were performed as necessary for completeness.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Group

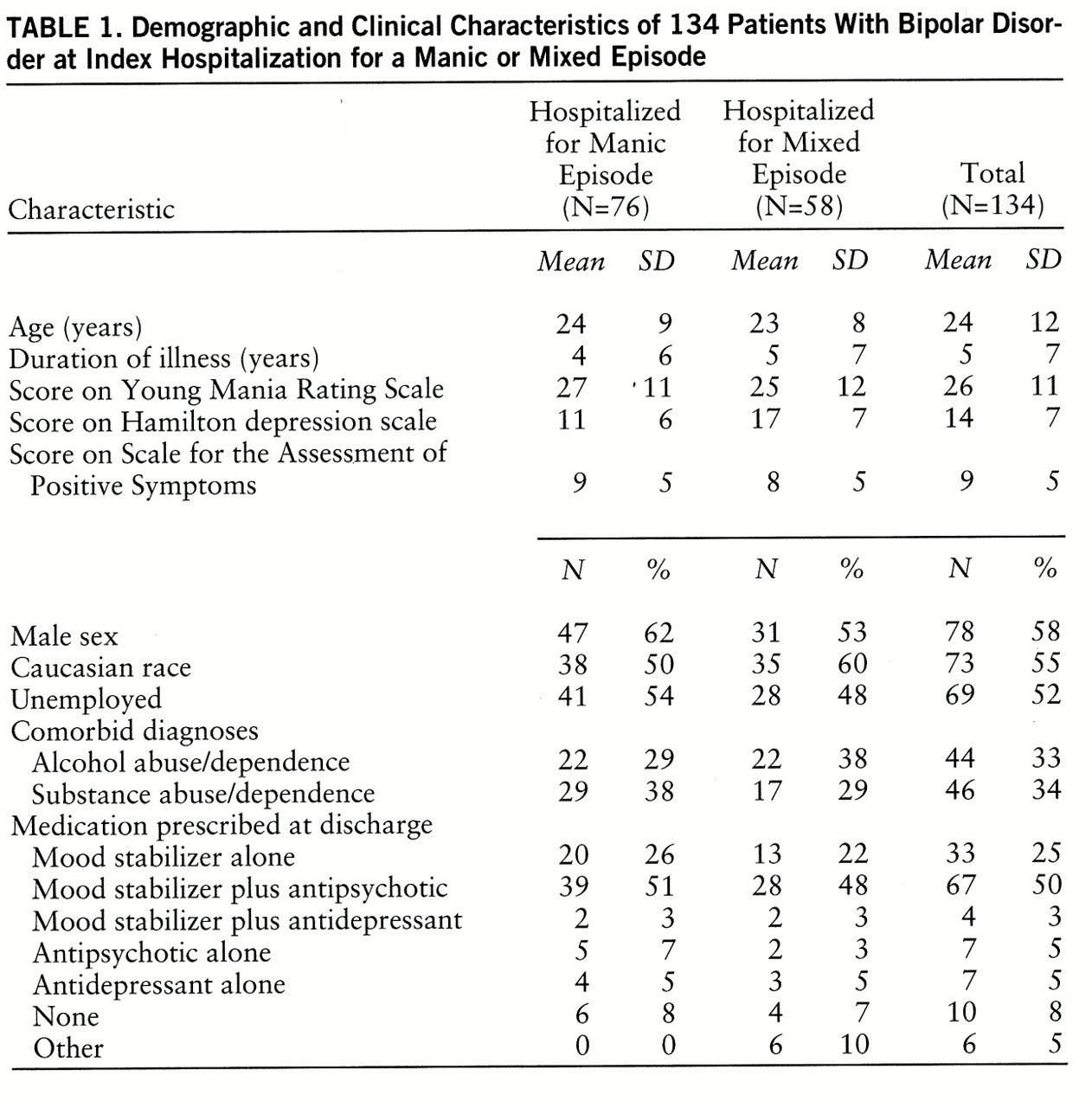

The clinical, demographic, and outcome variables of the study group are listed in tables

1 and

2. Patients who did not complete the study were more likely to have had a history of substance use disorders (13 [50%] of 26) than those who completed the 12-month follow-up (32 [30%] of 106) (χ

2=3.6, df=1, p=0.06). Otherwise, there were no significant differences between completers and noncompleters in any of the demographic or clinical variables assessed. Of the 106 patients who completed the 12-month follow-up, 55 (52%) met criteria for a substance-related disorder during the interval. These included 16 patients (15%) with drug abuse/dependence syndromes only, 14 (13%) with alcohol abuse/dependence only, and 25 (24%) with both syndromes. Thus, alcohol and substance abuse/dependence were highly correlated in these patients (phi=0.41, df=1, p=0.001) and, therefore, were not separated for additional analyses.

Manic Versus Mixed Outcome

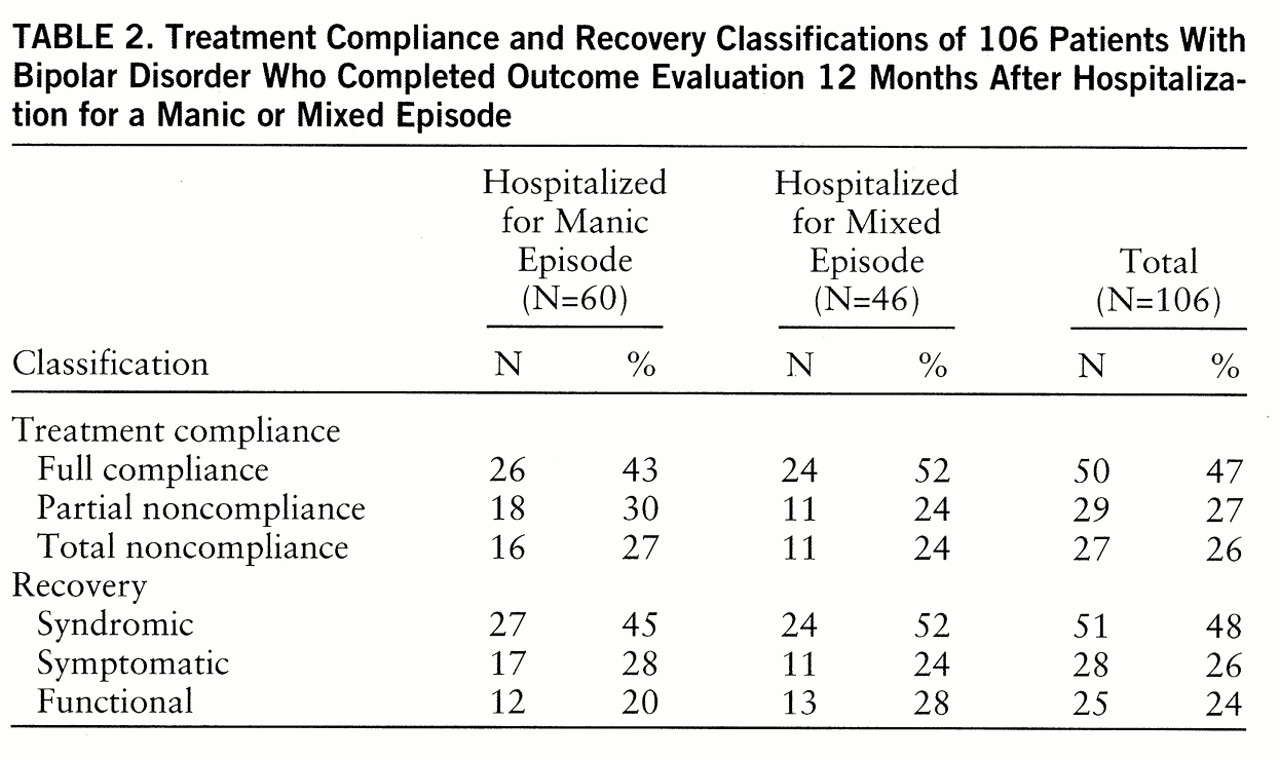

As shown in

table 2, there were no significant differences between patients with an initial diagnosis of manic or mixed bipolar disorder on any outcome variable.

Pharmacological Treatment and Compliance

Fifty (47%) patients were fully compliant, 29 (27%) were partially noncompliant, and 27 (26%) were totally noncompliant with pharmacological treatment during the follow-up period. Logistic regression revealed that only comorbid substance use disorders (χ

2=7.6, df=1, p=0.02) was associated with compliance. Specifically, patients with substance use disorders were less likely to achieve full compliance (N=34, 32%) than were patients without substance use disorders (N=61, 58%) (χ

2=7.8, df=1, p=0.02). Medication regimens prescribed at discharge are listed in

table 1. There were no significant associations among medication regimens prescribed at discharge and compliance or outcome measures.

Syndromic Recovery

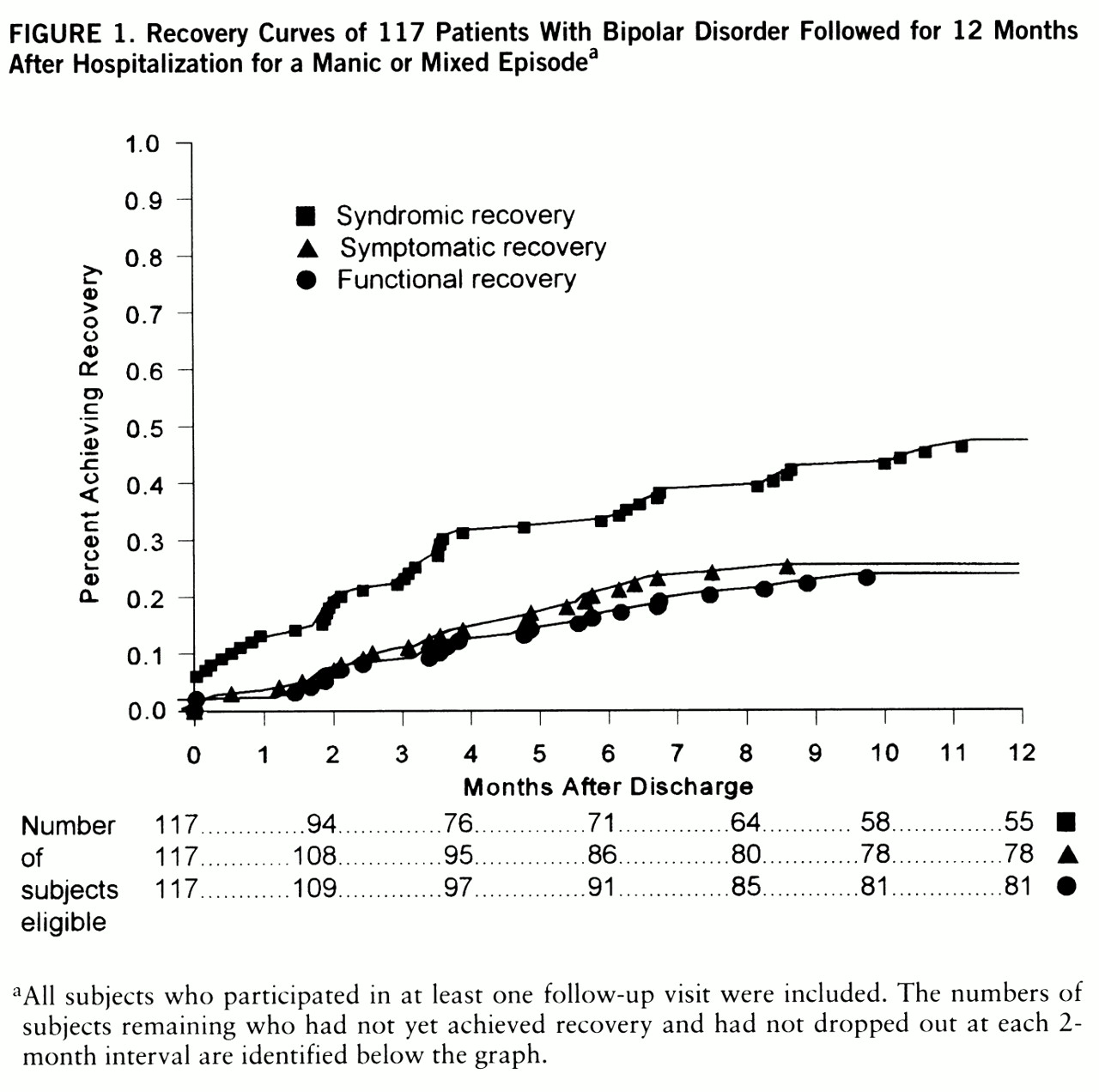

The survival curve for syndromic recovery is illustrated in

figure 1. Of the 106 patients who completed the study, 51 (48%) achieved syndromic recovery at some time during the interval between hospital discharge and 12-month follow-up. Logistic regression analysis revealed that only shorter duration of illness (χ

2=4.1, df=1, p=0.04) and full compliance (χ

2=4.2, df=1, p=0.04) were associated with syndromic recovery. Among 117 patients who completed at least one follow-up evaluation, according to Cox regression analysis, both shorter duration of illness (adjusted hazard ratio=1.07, 95% confidence interval=1.00–1.15; Wald χ

2=4.2, df=1, p=0.04) and full compliance (adjusted hazard ratio=0.66, 95% confidence interval=0.46–0.96; Wald χ

2=4.7, df=1, p=0.03) were significant predictors of less time to syndromic recovery.

Symptomatic Recovery

The survival curve for symptomatic recovery is illustrated in

figure 1. Of the 106 patients who completed the study, only 28 (26%) experienced symptomatic recovery at some time during the interval between hospital discharge and 12-month follow-up. Logistic regression analysis revealed that only higher social class (χ

2=6.2, df=1, p=0.01) was associated with symptomatic recovery. Using the Cox regression analysis, we found again that only higher social class (adjusted hazard ratio=1.17, 95% confidence interval=1.02–1.34; Wald χ

2=5.6, df=1, p=0.02) was associated with less time to symptomatic recovery.

Functional Recovery

The survival curve for functional recovery is also depicted in

figure 1. Of the 106 patients who completed the study, only 25 (24%) achieved functional recovery at some time during the interval between hospital discharge and 12-month follow-up. Logistic regression analysis revealed that, as with symptomatic recovery, only higher social class (χ

2=5.01, df=1, p=0.03) was associated with functional recovery. Using the Cox regression analysis, we found that higher social class (adjusted hazard ratio=1.21, 95% confidence interval=1.03–1.41; Wald χ

2=6.1, df=1, p=0.01) was also associated with less time to functional recovery.

Relationships Among Types of Recovery

By definition, all patients who achieved symptomatic recovery also experienced syndromic recovery. Eleven (39%) of the 28 patients who achieved symptomatic recovery had achieved syndromic recovery at least 1 month previ~ously; the remainder displayed both nearly concurrently. Syndromic recovery occurred in all patients who achieved functional recovery, preceded functional recovery by more than 1 month in five patients, and occurred more than 1 month later in two patients.

DISCUSSION

In this study, patients with an index manic episode did not differ significantly in outcome from patients with an index mixed episode of bipolar disorder. In contrast, other investigators (

7,

19) have reported poorer outcome for patients with mixed than with pure manic episodes. The profound influence of social class, treatment noncompliance, and duration of illness on outcome may have contributed to the lack of difference in outcome between patients with manic and mixed episodes.

Only 24% of our patients with bipolar disorder returned to premorbid function, and only 26% experienced symptom resolution during the year following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Less then half (48%) displayed sustained syndromic recovery from their affective syndrome. These findings are consistent with several other outcome studies of hospitalized patients with bipolar disorder. Harrow et al. (

4) observed that only 42% of 73 bipolar patients were functioning well 1.7 years following hospitalization for a manic episode. In a further follow-up of these patients, Goldberg et al. (

9) found that only 27% of 51 patients with bipolar disorder were functioning well 2 years after hospitalization for mania. Similarly, in a study of 73 patients with bipolar disorder who were experiencing their first episode of mania, Tohen et al. (

2) and Dion et al. (

13) reported that 40% were unable to work or study 6 months following hospitalization.

Our findings are also consistent with several other outcome studies of outpatients with bipolar disorder. O'Connell et al. (

5) observed that only 40% of 248 patients with bipolar disorder treated with lithium for 1 year displayed good psychosocial functioning. Coryell et al. (

6) reported that many patients with bipolar disorder experienced substantial deficits in psychosocial functioning despite syndromal and symptomatic recovery. Finally, in a 4.3-year (minimum 2 years) longitudinal study of 82 patients with bipolar disorder, Gitlin et al. (

10) found that most of the patients experienced persistent symptoms despite aggressive pharmacotherapy and that only 28% achieved good occupational outcome. Together, these studies indicate that a substantial proportion of patients with bipolar disorder experience persistent impairment following hospitalization.

In this study, we distinguished among syndromic, symptomatic, and functional recovery. Different risk factors were associated with each of these types of recovery, supporting these distinctions. Although all three types of recovery commonly co-occurred, many patients displayed one or two types of recovery but not all three. Furthermore, syndromic recovery frequently antedated symptomatic and functional recovery as the initial aspect of the recovery process. Symptom resolution usually preceded functional improvement as well, suggesting that recovery from manic or mixed episodes progresses through stages during which different clinical factors change in their relative importance (

12,

13). Thus, although full treatment compliance may be sufficient to produce syndromic recovery in most patients, additional interventions (e.g., psychosocial rehabilitation) may be necessary for symptomatic and functional recovery.

Not surprisingly, patients with full treatment compliance were more likely to achieve syndromic recovery. Patients with total noncompliance or partial noncompliance did not differ significantly in outcome, supporting the general assumption that full treatment compliance is an essential goal of pharmacotherapy for patients with bipolar disorder. Treatment noncompliance was also associated with comorbid substance use disorders. This suggests that comorbid substance use leads to medication noncompliance, that medication noncompliance may lead to substance use, or that both reflect poor insight into the need for treatment compliance and abstinence from substance use, respectively. Thus, substance abuse appears to have an indirect and deleterious effect on the course of bipolar disorder by means of its impact on medication compliance. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies (

2,

5,

8,

10,

12).

Higher social status was associated with symptomatic and functional recovery and with more rapid onset of recovery. The reasons for this are not clear, but it may reflect the effect of greater education and understanding of psychiatric illness as well as the availability of more extensive social and financial support systems. Our findings of an association between socioeconomic status and outcome are consistent with those of other studies (

4,

5,

14,

18).

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the subjects were patients hospitalized at a single treatment center, so the results may not be generalizable to other treatment settings. Second, the measures of recovery were similar, but not identical, to those used in previous studies. This may limit comparisons with some previous studies. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to use operational definitions of syndromic, symptomatic, and functional recovery in patients with bipolar disorder after hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Third, potential predictors of outcome identified in previous studies, such as age at onset (

14), number of previous hospitalizations (

4,

5), and number of previous episodes (

2,

10,

15,

17), were not examined in our analysis because of the need to limit the total number of variables for statistical purposes (

52). However, the duration of illness, a variable related to number of previous episodes and hospitalizations, was examined. Finally, although ours is one of the few studies to assess treatment compliance as a predictor of outcome (

10,

25,

31), medication plasma concentrations were not obtained. Therefore, compliance ratings were based on reports from patients, clinicians, and family members and may have been biased. However, previous studies that examined plasma concentrations to measure compliance found no higher rate of noncompliance than studies relying on patients' self-report (

56).

Despite these limitations, these results suggest that a substantial proportion of patients with bipolar disorder experience unfavorable outcomes and that unfavorable outcomes are associated with several specific prognostic factors.