In linkage studies, families with ill members are tested by genotyping the variable sequences (alleles) at DNA marker loci, which are unrelated to the disease. Each person has two alleles for each marker (one of maternal and one of paternal origin). If a disease gene is close to a marker, then offspring who inherit the disease allele will also tend to inherit a nearby marker allele (linkage), because meiotic recombination is unlikely across a short chromosomal distance. Linkage analysis determines whether ill relatives have inherited the same marker allele more often than expected by chance. If linkage analysis reveals that a disease gene is likely to be found near specific markers, intensive study of that region can be undertaken to identify the gene, determine its physiological role, and assess implications for treatment.

If the location of a gene can be predicted by pathophysiology or from rare cases with chromosomal defects, linkage studies can focus on these candidate regions. Such studies have not yet been successful for schizophrenia (

3). An alternative approach is the ge~nome scan strategy, which requires the genotyping and linkage analysis of a map of evenly spaced markers on all chromosomes. A genome scan can be expected to locate a single gene that causes most cases of a disease or (with larger samples) genes that independently cause disease in many cases or that greatly increase the risk of disease while interacting with other genes or nongenetic factors (

4–

6). The probability of detecting a gene can be predicted by the extent to which mutations in the gene increase the relative risk of disease in siblings of affected persons (cases) relative to the general population (λ

sibs) and by the frequency of the mutations (

7–

9). A gene of major effect causing a tenfold or greater increase in risk in all or most cases could be detected in 20–40 families, each with two or three ill members (

10). Such a gene would produce a simple dominant or recessive pattern of inheritance. For schizophrenia, total λ

sibs is about 10 (

2), but it is unlikely that this high relative risk is due to a single gene. The pattern of inheritance in families suggests that several genes interact to increase risk and that no one gene causes more than a two- to threefold increase (

9), suggesting non-Mendelian or complex inheritance. The sample size required to detect linkage increases as λ

sibs drops (particularly below 2) (

7,

11) or when a mutation is infrequent.

Like most current genome scans for schizophrenia, the present study was initiated almost 10 years ago and was based on the hypothesis that a gene or genes of major effect might be found in families with multiple cases of illness, even if more complex gene interactions were more generally typical of schizophrenia. Genome scans were considered the best way to test this hypothesis, with the hope that the discovery of such genes could elucidate pathophysiological mechanisms relevant to schizophrenia in general. These studies have been delayed by the difficulty of identifying and recruiting such families and the need to adapt to multiple changes in laboratory and statistical methods. In the meantime, several developments have cast doubt on the major gene hypothesis. No significant, replicable linkage finding has yet emerged (

3); and increased understanding of complex inheritance has led to an appreciation of the frequency of false positive results and of the large sample size required to detect genes of small effect (

11,

12).

Two previously published schizophrenia genome scans were completed in relatively small samples. Coon et al. (

13) studied mostly biallelic markers in nine Utah pedigrees with 35 affected individuals. Moises et al. (

14) studied microsatellite markers in five Icelandic pedigrees with 37 affected individuals and further investigated the 10 most positive markers in 65 pedigrees from multiple centers. Neither study yielded significant evidence for linkage. The present study is the largest schizophrenia genome scan published to date; others of similar or larger size are at or near completion. These emerging data serve as tests of the major gene hypothesis, whose full evaluation requires multiple rigorously conducted genome scans that use diverse samples, diagnostic approaches, and analytic methods. The results reported here are not significant. Given that this is the third genome scan that has failed to produce significant evidence for linkage, the field must squarely face the challenge of studying schizophrenia as a genetically complex disease (

15). We discuss below several issues concerning the interpretation of data from single and multiple studies, and whether these data can be used to locate schizophrenia susceptibility genes.

METHOD

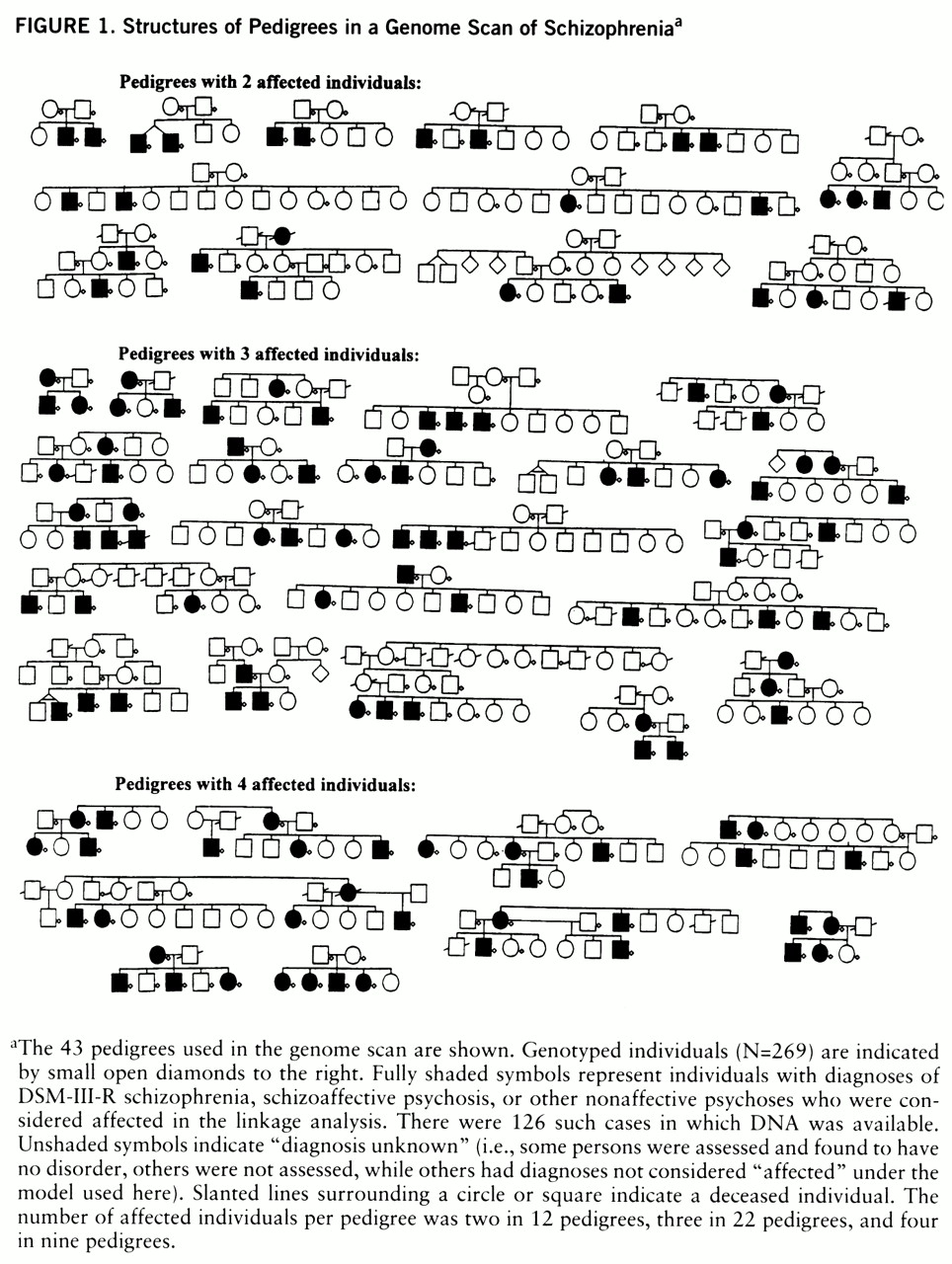

The 43 pedigrees (

figure 1) were ascertained in Australia (N=18), Philadelphia (N=14), Iowa (N=8), and New York (N=3); their ethnic backgrounds were European-Caucasian (N=31), African American (N=9), Caribbean-Hispanic (N=1), aboriginal/Micronesian (N=1), and Asian (N=1). Families suspected of having two cases of schizophrenia-related disorders were recruited from clinical and research settings and were included if there was a proband with chronic schizophrenia and either 1) at least two available first- or second-degree relatives with any related disorder or 2) a sibling with schizophrenia. Pedigrees were excluded if a bilineal family history of schizophrenia-related disorder in a relative within two degrees of the proband was demonstrated or suspected. Protocols were approved by human subjects committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Modified Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (

16) or Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (

17) diagnostic interviews (closely related instruments) were completed with probands and available relatives, and all relevant medical records were obtained for affected individuals. (Data from semistructured interviews for schizotypal and paranoid personality disorders, completed for nonpsychotic subjects, are not included in this analysis.) All available information was reviewed, and a lifetime DSM-III-R diagnosis was made by consensus of two senior diagnosticians at each site, followed by independent cross-site review (by L.S., J.E., D.F.L., and B.J.M.) and discussion of disagreements. Substantial efforts were made to ensure diagnostic consistency through these reviews. For Philadelphia/Australia, pairs of interviewers agreed on psychotic and mood disorder diagnoses in 26 of 27 cases (96%) with an interrater reliability (kappa) of 0.89 for mood and psychosis symptom items. For Iowa, interrater agreement was 93% and kappa was 0.86 for the category of schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis (primarily schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders). For New York, kappa for axis I disorders was 0.86. The cross-site procedure excluded 12.3% of reviewed cases from the genome scan analysis, mostly because of inadequate documentation.

DNA specimens were available for 126 affected persons, including those with schizophrenia (N=103) and those with other psychoses that co-aggregate with schizophrenia in families (

18–

20): chronic schizoaffective disorder (N=4), atypical (nonaffective) psychosis (N=16), delusional disorder (N=2), and schizophreniform disorder (with paranoid personality disorder) (N=1). To prevent inclusion of psychotic mood disorders, which can be misdiagnosed as schizoaffective disorder, we supplemented DSM-III-R criteria with definitions of “classical” mood features (severe melancholic or euphoric mood and associated mood symptoms) and excluded cases with these features. Nine cases of schizotypal or paranoid personality disorders were excluded because, while these disorders co-aggregate with schizophrenia, the relative risk is lower than for psychoses (

21). To encourage discussion of diagnostic differences across studies, we note from our experience in collaborations that our diagnoses of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are relatively conservative (i.e., in other studies, some of our atypical psychosis cases might be considered to be schizophrenia, and additional schizoaffective cases might be included), but our “other nonaffective psychosis” category is broader than the diagnosis of definite or probable schizophrenia in other studies.

Genotyping

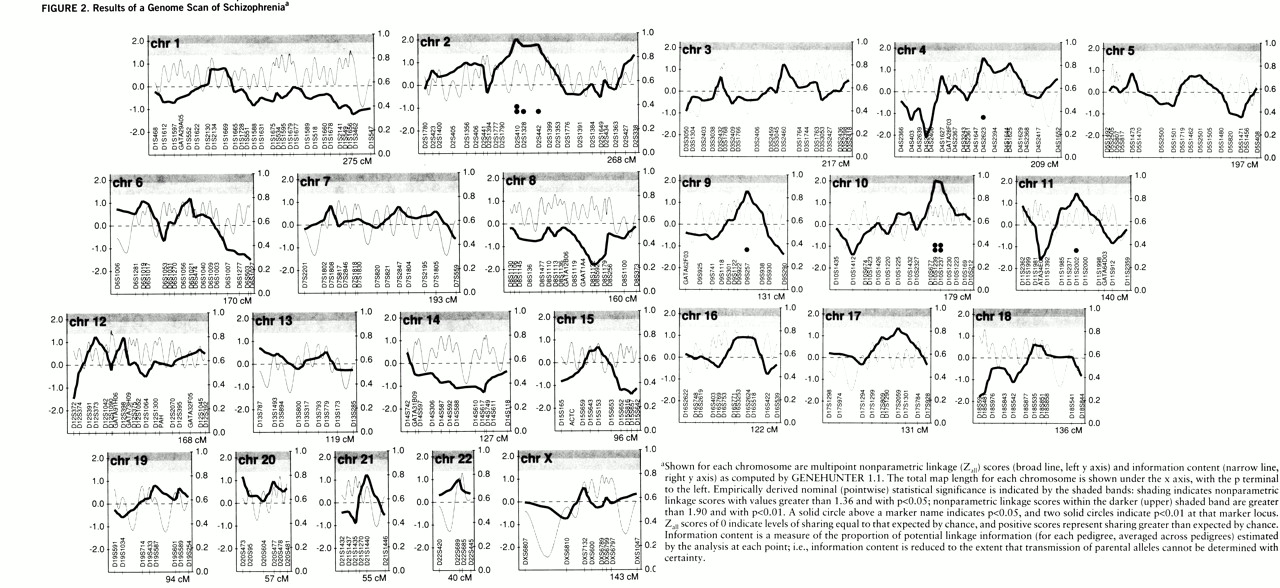

Genotyping was performed at Research Genetics, Inc., Huntsville, Ala., in 269 subjects, including affected persons, available parents and grandparents, and unaffected siblings when one or both parents were not available. From the 393-marker CHLC/Weber 6.0 map (Web site, http://genetics.mfldclin.edu/scrset/scrset.6), a map of 312 fluoresceinated autosomal and X-chromosome microsatellite markers was selected (by M.M.M. and A.K.) on the basis of a preliminary assessment of marker quality. Of these, 310 repeat sequences (241 tetra~nucleotide, 39 trinucleotide, and 30 dinucleotide) were included in the analyses (

figure 2), and two were excluded (see below). Marker names and locations are available by anonymous file transfer protocol: ftp.auhs.edu, (subdirectory)/docs/schiz, (file name)schizgen.dat. Total map length was 3,410 centimorgans (cM), with a mean intermarker spacing of 11 cM and a mean marker heterozygosity of 76%. Polymerase chain reactions (30 cycles) for each primer pair and subject were pooled and diluted according to a multiplexing scheme based on allele size range and dye type. Samples were denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes and loaded onto 12-cM-long 4% polyacrylamide/7 M urea 12-cm gels and run at 750 V for 1 hour and 10 minutes on a PE/ABI 377 sequencer. Dinucleotide repeats were run on 36-cm gels at 3000 V for 2 hours for higher resolution. Genotype data, generated by GENESCAN/GENOTYPER software (PE/ABI, Norwalk, Conn.), were reviewed and corrected by two independent readers and discarded in cases of disagreement, unscorable data, or peak heights below 20% maximum height for a given marker. A marker was included if 90% of subjects had scorable genotypes after Mendelian inheritance checking (PEDMANAGER, M.P. Reeve-Daly, unpublished). When Mendelian errors were detected, the marker was rerun for all members of the relevant pedigree, or for all pedigrees if five or more errors were observed for a single marker. Markers that persistently displayed high frequencies of non-Mendelian segregation, inconsistent amplification, or high recombination rates (according to GENEHUNTER's recombinant scoring method [22]) were discarded. For an estimate of reliability, markers tested independently (by M.M.M. and A.K.) with use of the same protocol were concordant in over 99% of subjects.

Statistical Analysis

Nonparametric linkage analysis was performed with GENEHUNTER 1.1 (

23). This is a model-free test of the exact probability of observed identical-by-descent marker allele sharing among affected individuals in each pedigree. It was chosen from available model-free methods (

24) because it can analyze small pedigrees with diverse structures. To maximize informativeness, multipoint analyses were performed for all markers on each chromosome simultaneously to determine the most likely locations of recombination events. The program also reports the proportion of potential linkage information captured, given the observed marker genotypes. The nonparametric linkage score (Z

all) is calculated as the sum of Z scores for each pedigree divided by the square root of the number of pedigrees. Simulation studies of our sample demonstrated high correlations (0.66–0.74) between nonparametric linkage scores and lod scores calculated under dominant, recessive, and intermediate models of schizophrenia inheritance (

25).

When parental DNA is not available, linkage statistics are more easily affected by the estimated allele frequencies for each marker. These estimates were based on those observed in the data set, and were calculated by PEDMANAGER, which counts alleles in founders including genotypes that can be inferred with certainty. Given the existence of small but significant racial differences in allele frequencies (

26,

27), we determined whether racial differences affected nonparametric linkage scores here. For the 54 markers on chromosomes 1 and 2, allele frequencies were estimated separately for the nine African American and 34 other pedigrees, nonparametric linkage scores were calculated for each subgroup, and a total Z

all score was computed by multiplying the square root of the number in the subgroup, summing these products for the two subgroups, and dividing the resulting sum by the square root of the total number of pedigrees. These scores were compared to those computed on the basis of allele frequencies estimated from the whole sample. Differences were minimal: the mean difference in Z

all scores was 0.04 and the maximum was 0.15, with differences greater than 0.10 for six markers (11%). Therefore, we report results based on allele frequencies estimated from the entire sample.

Since exact reported nonparametric linkage p values are conservative in the absence of perfect informativeness (

23), empirical p values were determined by computing Z

all for each of 5,000 simulated replicates (SIMULATE [28]) of the 43-pedigree sample for one unlinked marker with a mean information content of 0.78. From these data, a Z

all of 1.36 (250 of 5,000 replicates) was selected as the threshold for a p value of <0.05 (95% confidence interval=0.0441–0.0565), a Z

all of 1.90 (50 replicates) for a p value of <0.01 (95% confidence interval=0.0074–0.0131), and a Z

all of 2.59 for a p value of <0.001 (expected roughly once per very dense genome scan [29]) (95% confidence interval=0.0003–0.0024).

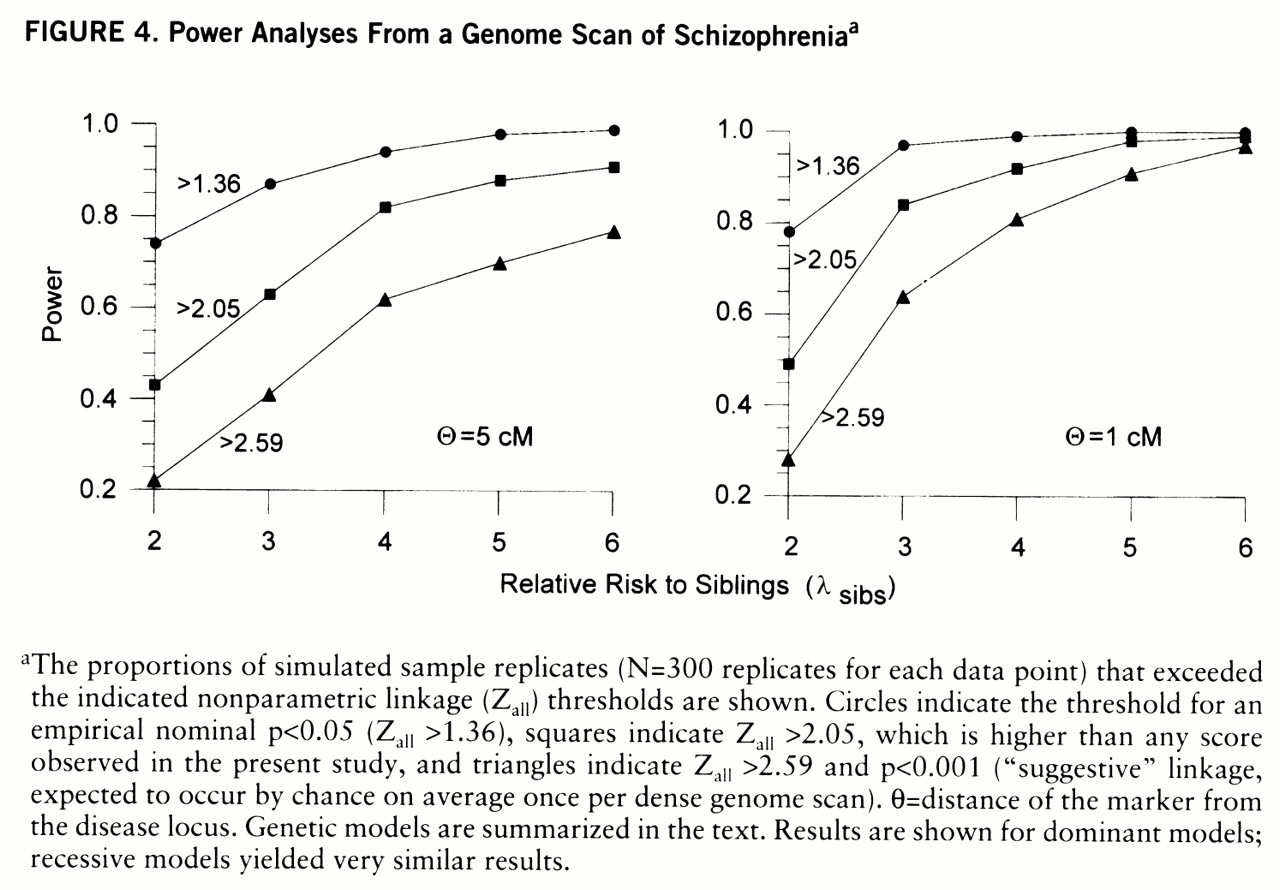

Power analyses were originally based on the hypothesis of a major single-gene effect; additional power analyses were performed to consider the alternative hypothesis of polygenic inheritance with lower values of λ

sibs (

29). When the simulation model assumed a major disease locus with λ

sibs of 10 or greater and either a dominant or recessive mode of inheritance, the power of the present sample was 0.91–0.99, with reduced power in the presence of increasing genetic heterogeneity (i.e., if the marker was linked to disease in a decreasing proportion of families) (data not shown). For dominant and recessive models with realistic population-based disease parameter values and λ

sibs values of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, nonparametric linkage scores were computed for each of 300 replicates simulated with use of each mode of transmission and λ

sibs value, assuming a single marker either 1 cM from the disease locus (very close to the marker) or 5 cM away (the maximum distance from a marker in a 10-cM interval). Simulated marker information content was similar to that in the genome scan (0.76–0.80). If f

0 is the penetrance of the normal genotype, f

1 is the penetrance of disease heterozygotes, f

2 is the penetrance of disease homozygotes, q is the disease allele frequency, and K

p is the population disease frequency, then for dominant and recessive models, respectively, f

0=0.001 and f

0=0.003; f

2 ranged from 0.023 to 0.10 and from 0.04 to 0.21; f

1=f

2 and f

1=f

0; q=0.036–0.14 and q=0.157–0.25; and K

p=0.0067–0.008 and K

p=0.00531–0.0081.

To avoid problems associated with multiple testing, no other analysis was performed for this sample with these markers. The only other published results for this sample used different markers to follow up others' findings on chromosomes 3, 6, and 8 (

30,

31), 22q (

32), and Xp13 (

22).

RESULTS

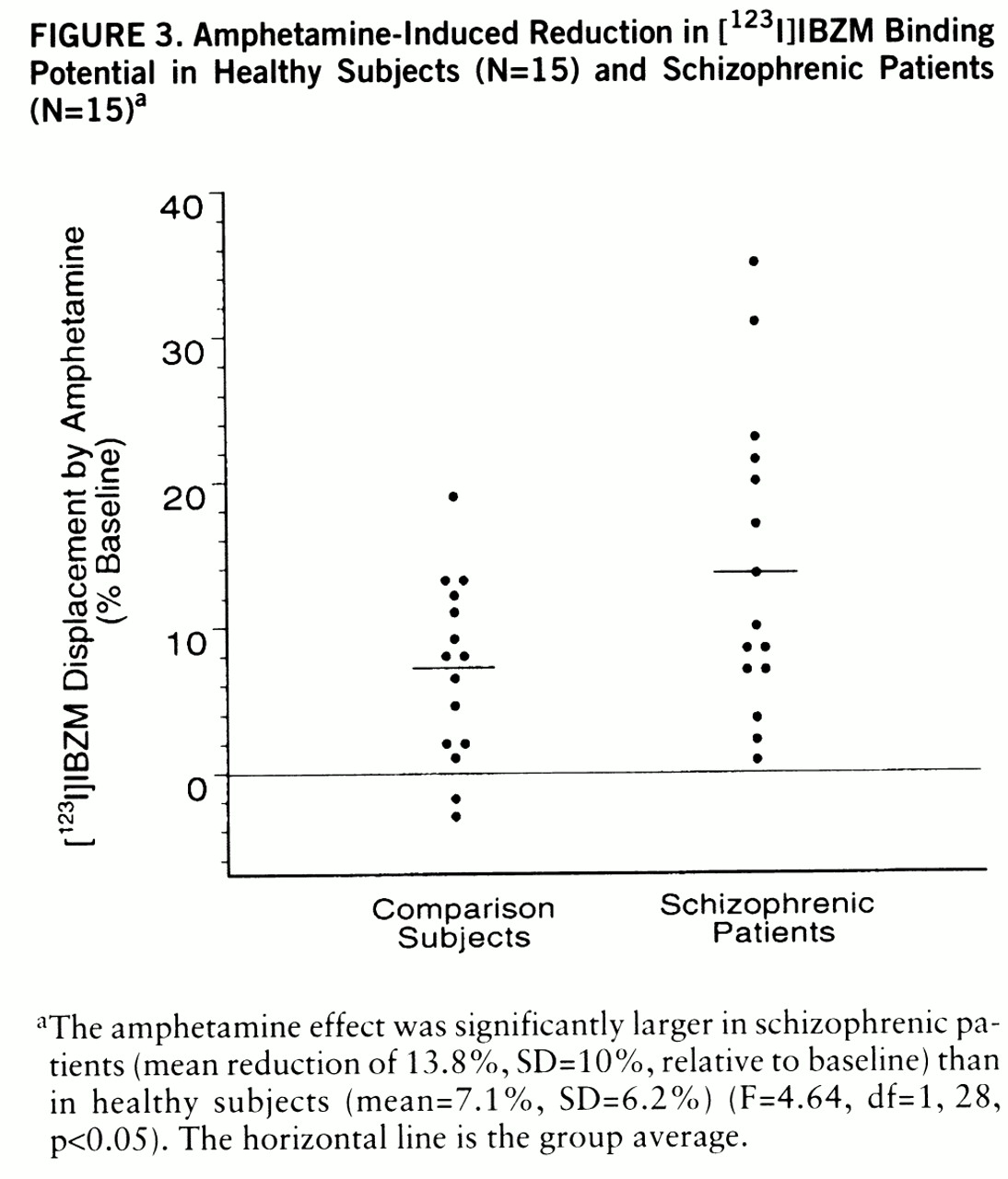

= Nonparametric linkage scores for all markers are displayed in

figure 2. Their distribution is shown in

figure 3; superimposed is the theoretical normal curve for the mean (0.009) and SD (0.738), to which the observed data fit at p=0.96 (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and with minimal skewness (0.268) and kurtosis (0.022). The standard deviation of Z

all is reduced below the expected value of 1 when markers are not fully informative. Marker names and locations, nonparametric linkage scores, p values, and information content are available from our anonymous ftp site as described above.

An empirical p value less than 0.05 was observed at eight markers (not significantly different from the 15 of 310 such p values expected by chance), and an empirical p value less than 0.01 was observed at three of these markers (the expected number). On the five chromosomes containing these eight markers, the peak values for each chromosome (with the chromosomal band shown in parentheses) were: p<0.01 for Zall=2.02 at marker D10S1239 (10q23) and Zall=2.01 at D2S410 (2q12-13); and p<0.05 for Zall=1.51 at D4S2623 (4q22-23), Zall=1.54 at D9S257 (9q22), and Zall=1.44 at D11S2002 (11q21).

For power analyses,

figure 4 shows probabilities of exceeding three nonparametric linkage score thresholds: 2.59 (nominal p<0.001), 2.05 (i.e., power to detect a larger score than any in the present data), and 1.36 (p<0.05). There is good power to detect Z

all=2.59 for a marker 1 cM from the disease locus with λ

sibs=3; but for a marker 5 cM from the disease locus, there is high power (85%) to detect Z

all=2.05 only when λ

sibs values are 5 and above. With λ

sibs values between 2 and 3, scores between 1.36 and 2.05 are common, and similar scores would be seen for a locus with a higher λ

sibs value in 50% of the families (unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

Although p values below the 0.05 level of significance were observed at eight markers in five chromosomal regions, linkage studies require more stringent thresholds. For a single-gene disease, the size of the genome (the number of independent regions tested) must be considered, so that a “nominal” p value of about 0.0001 is equivalent to a 5% genomewide false positive rate

(4, p. 65). For complex disorders, a different threshold must be computed, because there is no certainty that linkage will be found. Lander and Kruglyak (

29) showed that with complete information (i.e., a dense scan using one analysis), nominal p<0.00002 would occur by chance about once per 20 scans (genomewide p≈0.05), and nominal p<0.001 about once per scan (which these authors suggest as a criterion for “suggestive linkage”). Alternatively, simulation-based thresholds can be determined (

4,

29); see Holmans and Craddock (

33) for an example. By either approach, the present positive results cannot be considered statistically significant.

Thus, the present results do not support the hypothesis of a major gene effect in these families, consistent with the two previous scans (

13,

14). A major gene could exist in certain populations, in a chromosomal region not well covered by our map, or in an undetermined subgroup of families. Alternatively, susceptibility to schizophrenia could be largely due to an interaction of several genes, each with a small effect on disease risk (

1,

9). Detection of these genetic effects could require larger samples than currently exist, perhaps 500–1,000 pedigrees (

11,

12). Multiple loci that interact to increase disease risk are difficult to detect, since each parent may carry several susceptibility alleles; multiple, distinct combinations of these alleles might contribute to disease in different children and in different pedigrees. Thus, for any one locus, the pattern of allele sharing among ill relatives is variable and complex. Among smaller samples, statistical support for linkage will vary because of random (stochastic) variation in the proportion of families in whom disease is associated with inheritance of a particular parental susceptibility allele (

34). In any one sample, chromosomal regions containing these genes are the most likely to produce high scores, but the same regions will produce weakly positive and negative scores in some samples. By chance, scores in the same range may be observed in regions that do and that do not contain disease genes, making true and false positives difficult to distinguish statistically.

In this study, we chose to preserve statistical power by applying a single robust linkage test to one diagnostic model, avoiding the need to adjust p values for multiple testing (

23,

29). Some statisticians advocate the use of multiple tests for diverse genetic and diagnostic models, so that the maximum number of true positive regions will be identified as deserving of further study (

35), while others advocate the use of at least one dominant and one recessive inheritance model (

36). Every approach has potential strengths and limitations. Nonparametric linkage can be used as a single test in a genome scan because it correlates so highly with tests of diverse models of inheritance (

23,

25).

Since methodological problems may complicate interpretation of linkage studies, the failure to detect linkage in a single study does not disprove the major gene hypothesis. No report has yet identified a statistically significant finding after correction for multiple testing (

3,

13–

15,

37–

41). It is possible that current psychiatric diagnostic criteria obscure major gene effects by classifying genetically diverse subjects together, although this is difficult to test. Therefore, the present results, taken together with other available evidence, fail to support the hypothesis that a major gene effect is present in multiply affected families.

Given the failure of individual studies to yield statistically significant results, investigators are proceeding by genotyping additional markers near each study's most positive findings, often in expanded samples. If significant linkage cannot be detected and replicated, it is feasible to identify known genes in candidate regions that have CNS activity, and to determine whether mutations or allelic variations in these genes distinguish ill from well subjects. But many CNS genes remain unknown, and it is currently too costly to sequence the DNA in all candidate regions to search for these genes, given that the number of candidate regions will proliferate as more studies are reported.

It is possible that collaborative studies of multiple existing samples can provide the power necessary to narrow the search. The first such efforts have produced results that are suggestive (p<0.001) but not significant in large samples studied on chromosomes 6p, 8p, and 22q as discussed below. Final published data from a larger number of scans may reveal certain regions that are among those with the most positive results in several scans. Pragmatically, this is a reasonable basis for selecting regions for more intensive study, but with the caveat that the number of false positive results will proliferate with the number of scans, so that overlapping positives can occur by chance. Adequate evaluation of these regions would require collaborative efforts in which the same markers and statistical analyses are used in multiple samples selected in an unbiased manner (i.e., without regard to their findings in the region under study) (

31).

Comparisons With Findings From Other Studies

We summarize here the published findings from other studies in the regions that showed the most positive results in the present study, as well as regions in which positive evidence has been reported in a number of other studies. Note that the various lod scores mentioned achieve genomewide significance somewhere between values of 3.3 and slightly over 4.0, and none is significant after correction for multiple testing.

Chromosome 2q. Five Icelandic pedigrees had positive findings at marker D2S135 (p=0.000001 by the weighted pairs correlation test—extreme p values for nonparametric tests in very small samples are generally interpreted cautiously), 7 cM toward the centromere from our peak, but in their second-phase multicenter study of two 2q markers in 65 pedigrees the results were negative (

14). A maximum lod score of 1.71 was reported in 14 American and Austrian pedigrees at D2S44 (32 cM toward the q terminal from our peak) for a broad diagnostic model (

42).

Chromosome 4q. Our peak is more than 60 cM from other chromosome 4 findings for neuropsychiatric disorders (

13,

43,

44).

Chromosome 9q. Moises et al. (

14) reported p=0.05 at D9S175 in five Icelandic pedigrees (about 20 cM toward the centromere from our peak) and p<0.01 in their phase 2 sample. Increased chromosome 9 pericentromeric inversions were reported in schizophrenia (

45), but findings in linkage studies were negative (

46).

Chromosome 10q. There are no published positive findings in this region.

Chromosome 11q. In a large pedigree, schizophrenia was associated with a 1;11 balanced translocation (breakpoint between TYR and D11S388, 5 cM toward the centromere from our peak), although the authors suggest that relevant genes are more likely to be on chromosome 1 (

47). This region has been of interest because the dopamine D

2 receptor gene is about 14 cM away (toward the centromere). A very positive lod score was observed in one of four large French Canadian pedigrees (

48), but negative or inconclusive results were reported in multiple other samples (

49–

56).

Preliminary results have recently been reported for a number of additional genome scans (

37–

41,

57,

58), but evaluation must await the full published reports.

Our most positive results did not include several regions for which stronger evidence for schizophrenia linkage has been reported by others. An initial positive result on chromosome 22q (

59) was followed by a report of suggestive linkage (p=0.001) in a multicenter study (

32) that included data from the present sample. These findings are near (but not within) the deletion region for velo-cardio-facial syndrome, which can be associated with schizophrenia (

60,

61) or mood cycling (

62). On chromosome 6p, a result close to significant linkage was reported in one sample (

63) and suggestive linkage in another (

64), as well as in a multicenter study (

31) that included results from the present sample (

30). For chromosome 8p, an initial positive report (

65) was followed by reports of suggestive linkage in another sample (

66) and in a multicenter analysis that included that latter sample and the present sample (

31).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Strengths of the present study include independent cross-site review of diagnoses; a map of highly polymorphic markers, most of them trinucleotide and tetranucleotide repeats (which are less prone to genotyping and scoring error than dinucleotide repeats); and the use of a single, robust, multipoint model-free analysis.

Limitations include small sample size and gaps in the map that reduce power in those regions (including some telomeres, as in all current maps). A possible limitation is the sample's racial and ethnic diversity. Since the prevalence and symptoms of schizophrenia are similar around the world, and no familial subtypes have been found, it has been suggested that the same genes determine susceptibility across racial/ethnic groups (although groups may carry different mutations in these genes) (

67). However, genetic mechanisms underlying complex traits can differ across populations (

68), and this could be true for schizophrenia. For example, chromosome 6p has produced strikingly positive linkage scores in a large Irish sample (

63) but not in most other samples (

3,

31). There might be a gene on chromosome 6p in which mutations that increase the risk of schizophrenia are more frequent in the Irish than in other groups. Or, differences in linkage scores could be due to methodology (e.g., diagnoses) or stochastic variation. We do not yet know whether homogeneous populations will produce more consistent results. Population differences in marker allele frequencies also influence linkage scores, but we observed only slight changes when frequencies were calculated separately for African American pedigrees. Effects of allele frequencies are minimized when DNA from most parents is available and multipoint analysis is used, as in the present study.

Other limitations, common to all schizophrenia research, include reliance on purely clinical diagnoses and lack of evidence for inherited subtypes. Our diagnostic model (which included schizophrenia-related psychoses but not schizotypal or paranoid personality disorders) is well supported by family studies, but other models might be more powerful. Certainly, the field of schizophrenia research in general would benefit from an examination of differences in diagnostic decisions across studies.

In conclusion, we completed a genome scan of 43 schizophrenia pedigrees and observed nominally significant results in five regions, but no genomewide statistically significant or suggestive linkage. The initial hypothesis of a major gene effect in these multiply affected families was not supported. We plan to study the regions with our most positive results in an expanded sample and with denser marker maps. As additional genome scan results are published, it may be possible to identify chromosomal regions that produce positive results in multiple studies. We urge more systematic collaborative efforts to combine existing samples for the study of these regions, in order to determine whether strong evidence for linkage can be observed in sufficiently narrow regions to permit the identification of schizophrenia susceptibility genes with the use of current technologies.