Dissociative identity disorder (DSM-IV), also known as multiple personality disorder, has been the most extensively studied dissociative disorder in the last decade (

5,

6). It is considered the most severe manifestation of dissociative psychopathology that is closely related to child abuse (

7). There is growing interest in this previously neglected diagnostic category among clinicians and researchers in several countries (

8–

13). Studies conducted with standardized assessment measures in North America (

14), The Netherlands (

15), and Turkey (

16) reported similar symptom profiles, supporting cross-cultural consistency of the disorder.

Dissociative symptoms have traditionally been considered quite common in Turkey, especially in emergency psychiatric wards and emergency units of general hospitals (

17–

19). Dissociative states were usually conceived of as acute and self-limited clinical conditions that tend to be recurrent; an underlying, chronic, complex dissociative psychopathology was never taken into consideration. Dissociative states have been linked to developmental conditions characterized by restriction, oppression, neglect, and even hostile rejection in the family of origin (

19–

21); however, the relation to childhood traumata, especially sexual and physical abuse, was not included as part of today's trauma paradigm (

22). Consequently, the direct traumatic origins of current symptoms were not taken into consideration in the psychotherapeutic treatment of these patients (

23–

25).

In the present study, we attempted to determine the rate of dissociative disorders in psychiatric inpatients in Turkey using standardized assessment instruments. To our knowledge, this is the first study scanning dissociative identity disorder among psychiatric inpatients in our country. We also attempted to determine the differences between patients with the diagnosis of dissociative disorder and those who reported few dissociative symptoms. An additional reason for using such a comparison group and interviewing the two groups in a blind fashion was to eliminate bias in the assessment of these patients. To eliminate any false positive findings, all patients given the diagnosis of a dissociative disorder according to results of the structured interview were evaluated by a clinician. Additionally, information about the frequency of childhood abuse, suicide attempts, and self-mutilative behavior was gathered by using a self-report questionnaire; details of related results will be published elsewhere.

RESULTS

During the research period, 261 consecutive patients were admitted to the inpatient wards. Twenty patients were excluded for the following reasons: six had been previously diagnosed as having dissociative identity disorder, six had mental retardation, and eight were illiterate. Of the 241 remaining patients, 166 (68.9%) completed the questionnaires (63.6% of all admissions). The reasons for not completing the questionnaires included being hospitalized for too short a time, refusal to participate, or being too psychotic to be invited.

There was no significant difference in the ages of the patients who did not participate (mean=31.6 years, SD=11.3) and those patients who did (mean=32.1 years, SD=12.0) (t=0.33, df=231, p>0.05). Twenty-one (8.7%) of the 241 patients were younger than 18. Women made up 58.4% (N=97) of those who completed the questionnaires and 53.3% (N=40) of those who did not complete them; this difference was not significant (χ2=1.25, df=2, p>0.05). The age range of the participating patients was 13–70 years. There was no significant difference in age between women (mean=32.0, SD=12.2) and men (mean=32.3, SD=11.8) (t=0.16, df=164, p>0.05).

The mean Dissociative Experiences Scale rating of the original 166 patients was 17.8 (SD=14.9, range=0.0–77.9, median=14.6). Twenty-four (14.5%) of the 166 patients had a score higher than 30, and 56 (33.7%) had a score higher than 20. Women (mean=19.7, SD=16.9) had a higher score than men (mean=15.0, SD=11.0) (t=2.04, df=164, p<0.05). Age correlated negatively with scale score (r=–0.27, N=166, p<0.001). Six of the patients with a score higher than 30 were men and 18 were women. However, there was no difference in gender between patients with a score higher than 30 and those with a score of 30 or lower (χ2=3.17, df=1, p>0.05). Patients with scores above 30 (mean age=27.0, SD=11.4) were younger than those with scores of 30 or lower (mean age=33.0, SD=12.0) (t=2.28, df=164, p<0.05).

Twenty-one of the 24 patients with scores above 30 could be evaluated with the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule. Two patients were hospitalized for too short a period, and one refused to participate in the interview. This sole refusing patient told the interviewer that he was deeply affected by the content of the Dissociative Experiences Scale and was afraid that a further evaluation “might elicit something” in him.

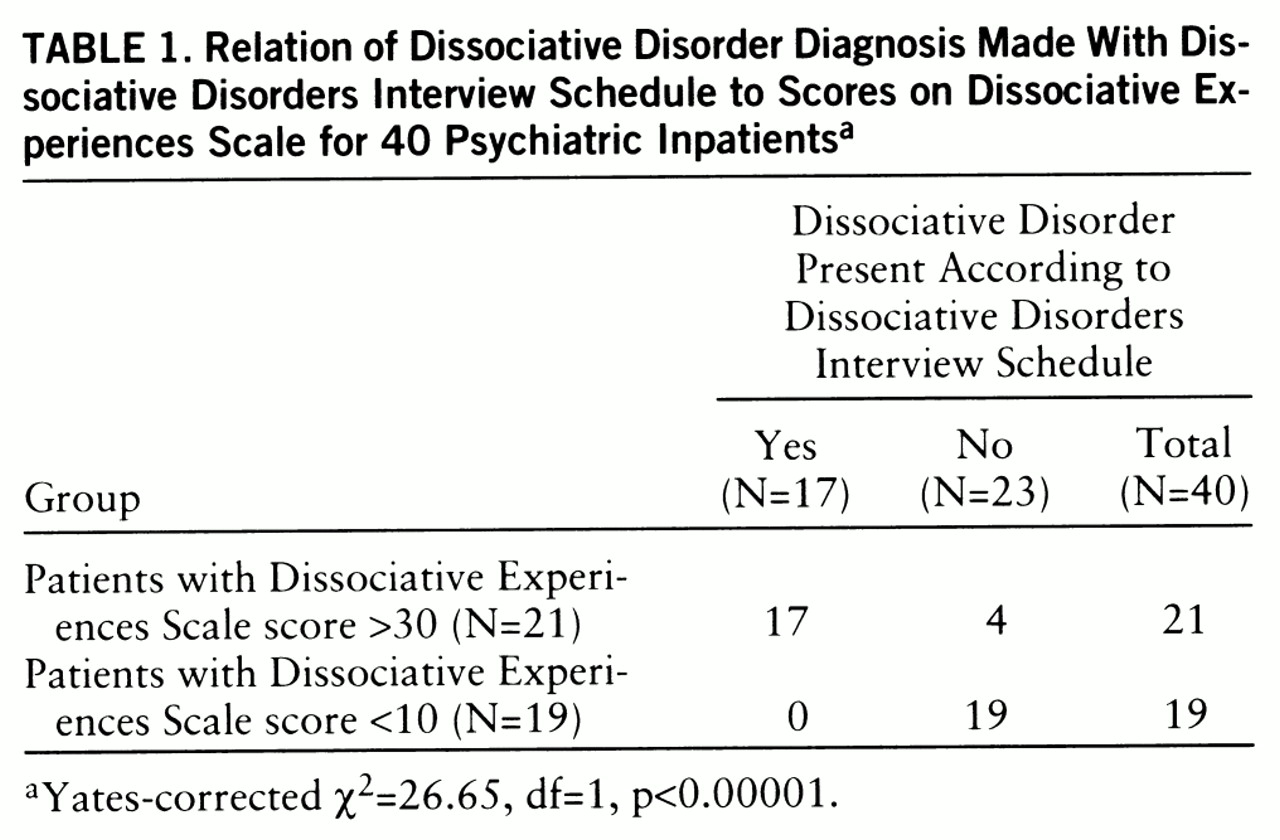

Seventeen of the 21 patients with Dissociative Experiences Scale scores above 30 were diagnosed as having a dissociative disorder according to the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule. The remaining four patients had other diagnoses: one had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and three had schizophrenic disorder. None of the patients with Dissociative Experiences Scale scores below 10 had the diagnosis of a dissociative disorder (

table 1). Sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 83%, respectively, positive predictive power was 81%, and negative predictive power was 100%.

Eleven (eight women and three men) of the 17 patients with a dissociative disorder had the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder according to the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule. The remaining six patients were diagnosed as having dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. Dissociative identity disorder and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified were considered supraordinate diagnoses. Any patient who met criteria for dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, or depersonalization disorder and also met criteria for dissociative identity disorder or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified received the overall diagnosis of either dissociative identity disorder or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

Nine patients (seven women and two men) were diagnosed as having dissociative identity disorder by clinical examination. The remaining eight patients were diagnosed as having dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. In six of these patients, some personality states were observed repeatedly, but they were not considered sufficiently distinct and separate to diagnose a dissociative identity disorder at this stage of the evaluation. A 45-year-old male patient from this group had the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder according to the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule, but he declared that he did not want his alter personalities to be evaluated.

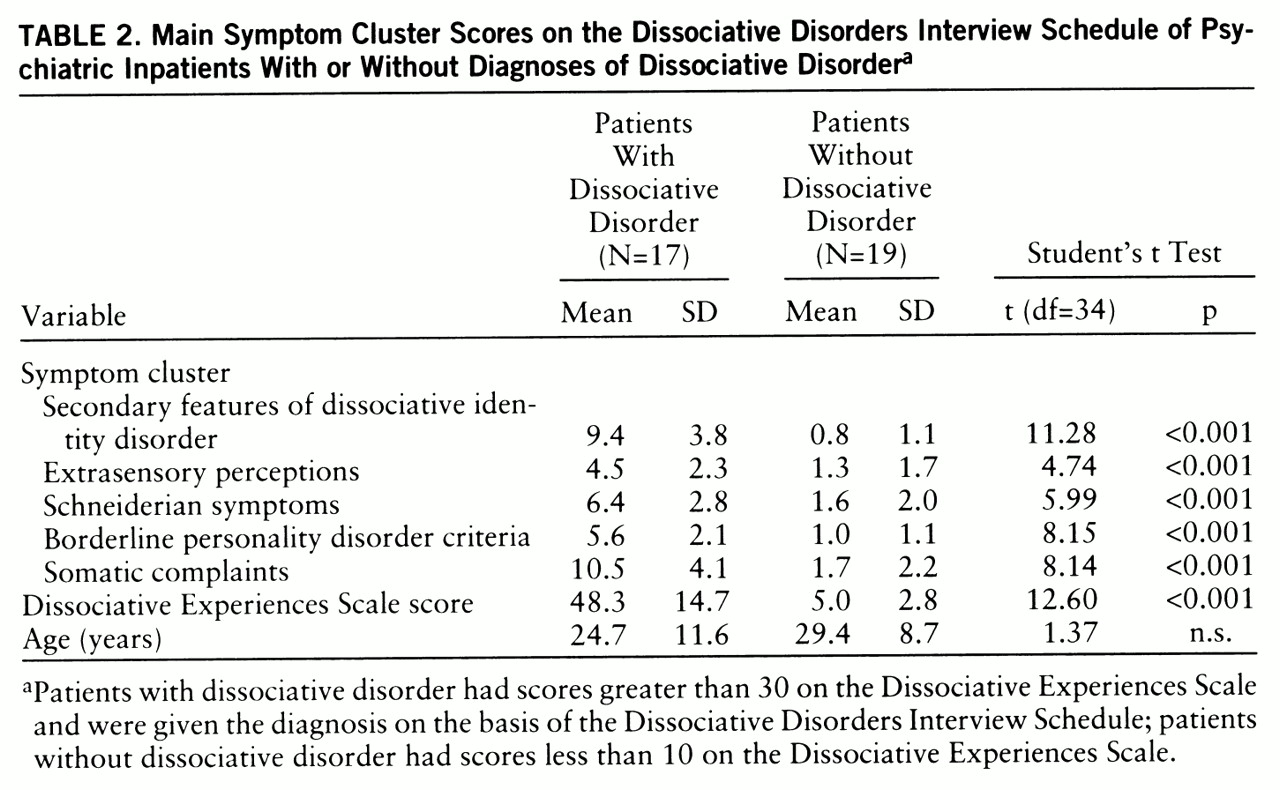

Findings from the main symptom clusters of the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule and the Dissociative Experiences Scale scores for the two groups are presented in

table 2. The patients with a dissociative disorder had significantly higher scores in all main symptom clusters and on the Dissociative Experiences Scale.

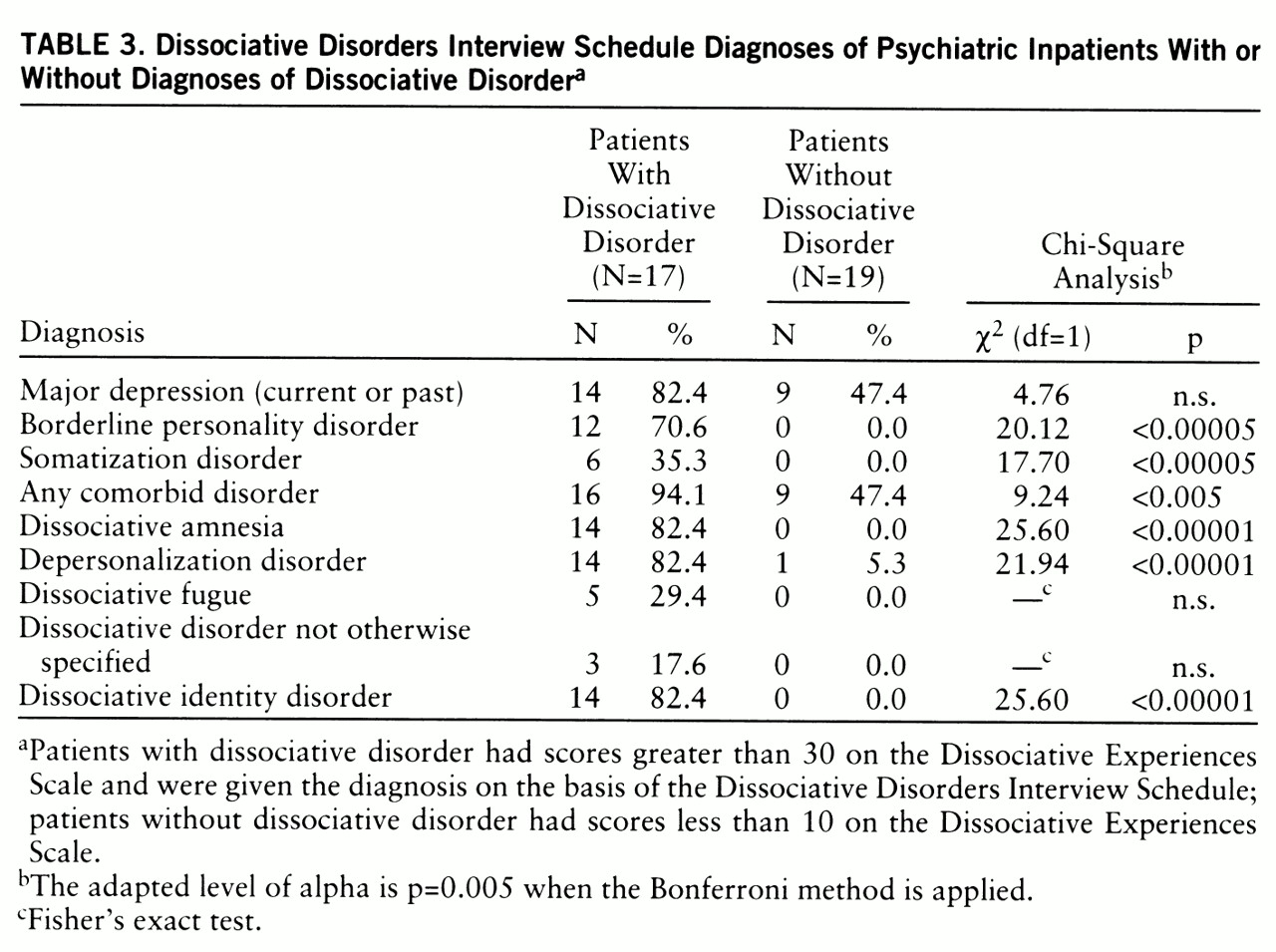

Table 3 indicates the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule diagnoses that the patients in both groups received. All patients in the dissociative disorders group met DSM-III-R criteria for a dissociative disorder. Most of them had comorbid psychiatric disorders. There were high rates of comorbid borderline personality disorder, current or past episode of major depression, and somatization disorder.

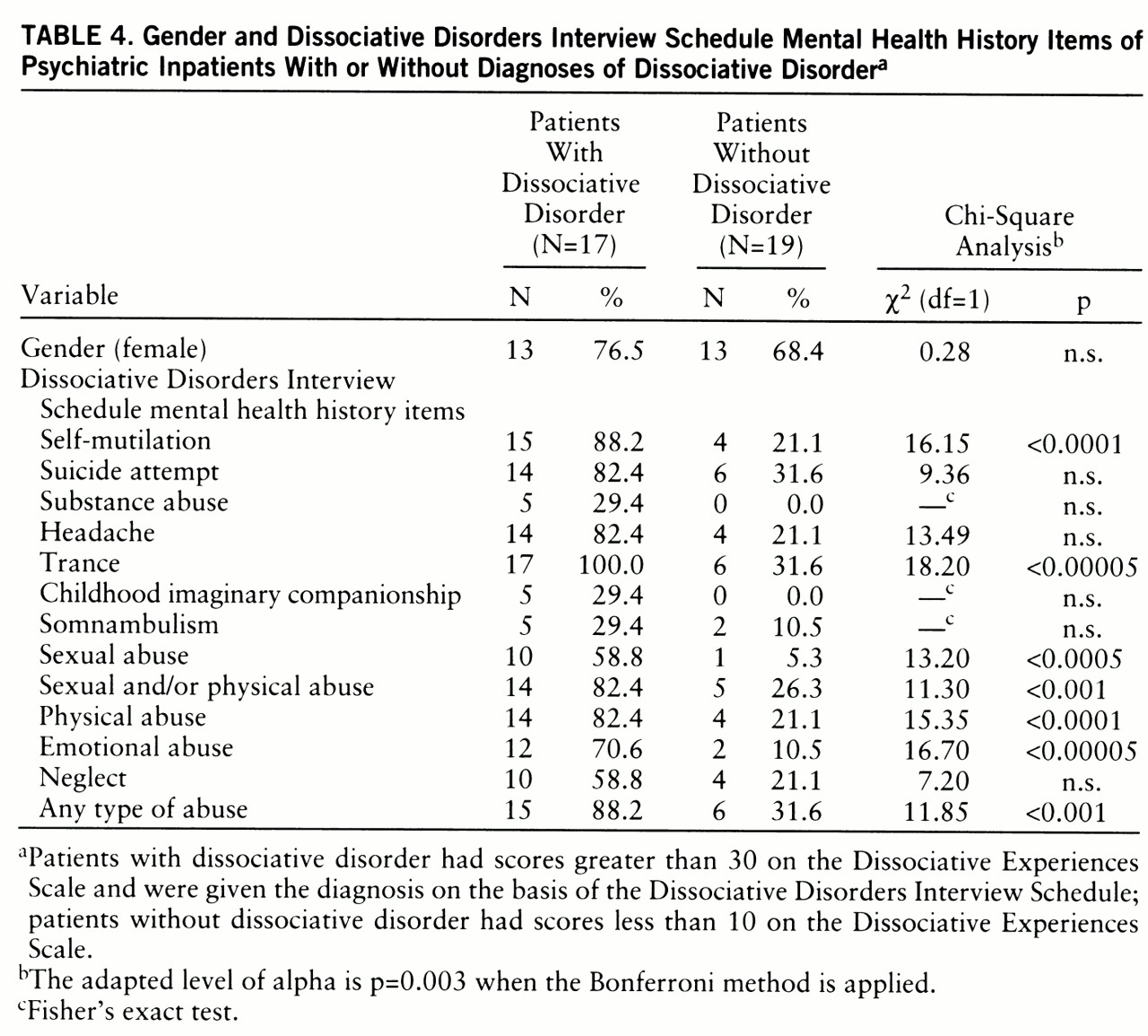

Table 4 shows some findings concerning mental health history derived from the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule. Significantly more patients in the dissociative disorders group than in the comparison group reported physical abuse and sexual abuse (

table 4). More of the patients with dissociative disorder than patients in the comparison group also reported emotional abuse.

Sixteen of the 17 patients in the dissociative disorders group had contacted a psychiatrist previ~ously. The mean interval between their first psychiatric contact and the study interview was 4.6 years (SD=4.6, range=3 months–15 years). Seven of these patients had been hospitalized at least once (range=1–6 times). Nine had been given diagnoses of depression, one mania, two schizophrenic disorder, and two anxiety disorder. Eleven had been prescribed psychotropic medication. Two of the subjects had received ECT; nine had received antipsychotic medication, 13 had received an antidepressant, and two had received lithium. Fourteen of the subjects said that they had received ineffective treatment at some time. Only five of the subjects had received courses of psychotherapy. For all but one of them the psychotherapeutic intervention ceased in fewer than 10 sessions. The only exception was an incest victim with the diagnosis of depressive disorder who had received both biological and psychotherapeutic treatment for 6 years; her care was covered by a women's shelter in Istanbul (Mor Cati [Purple Roof]).

DISCUSSION

Of all consecutively admitted patients to an inpatient psychiatric unit, 63.6% could be recruited for the present study. This rate is similar to those of Ross et al. (

33) and Saxe et al. (

34) and higher than those of Latz et al. (

35) and Modestin et al. (

36). On the basis of our findings in the current study, the conservative estimate of the frequency of new cases of dissociative disorders among psychiatric inpatients is 10.2%, including 5.4% with dissociative identity disorder. These are the percentages of subjects who received the diagnosis from both the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule and the study clinician.

To our knowledge, there are few studies using a structured interview to determine the rate of dissociative disorders among psychiatric inpatients (

13,

33–

36).

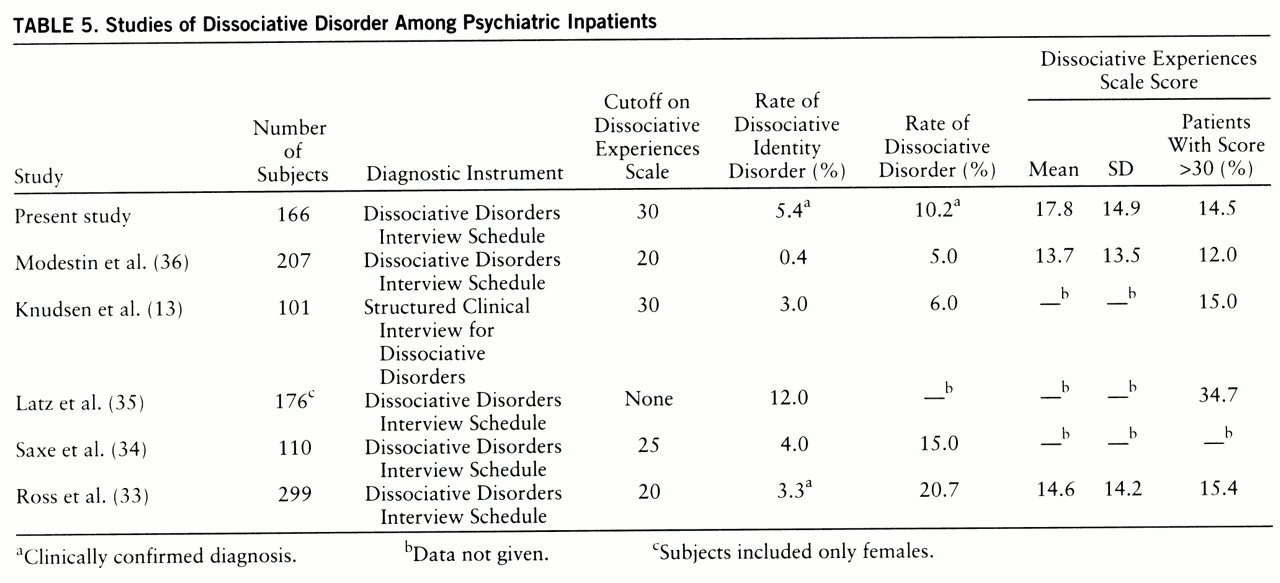

Table 5 presents the results from several studies. The rates in our study are in agreement with those of studies in North America and Norway despite the higher cutoff score in our first phase. A study on a Swiss sample (

36) found lower rates. Whether this difference depends on cultural influences or is caused by different inpatient sample characteristics is not yet known.

Most of the patients with dissociative disorders in our study group had comorbid psychiatric disorders according to the structured interview. There were high rates of comorbid borderline personality disorder, current or past episode of major depression, and somatization disorder. Approximately two-thirds of our study group met criteria for borderline personality disorder. This finding is in agreement with that of Saxe et al. (

34). However, in a case series of mostly outpatients with dissociative identity disorder (

16), we found that the rate of borderline personality disorder was much lower, suggesting that patients fitting these criteria are hospitalized more frequently.

It is not uncommon for patients with dissociative identity disorder to meet DSM-IV criteria for several other disorders at the same time (

14–

16). Although dissociative identity disorder and borderline personality disorder have their own diagnostic features, there is a wide phenomenological overlap. On the other hand, Modestin et al. (

36) determined that Dissociative Experiences Scale scores correlated positively with a number of features of practically all personality disorder subtypes.

Significantly higher rates of childhood traumatic experiences were found in our patients with a dissociative disorder than in the comparison group. This finding supports the notion that traumatic childhood experiences play a major role in the development of dissociative disorders (

7,

22). Saxe et al. (

34) found that PTSD was also frequent among inpatients with a dissociative disorder. Self-destructive behavior such as self-mutilation, suicide attempts, and substance abuse were also common in our dissociative disorder group. This type of behavior also has been linked to childhood trauma (

37).

The Dissociative Experiences Scale ratings of our inpatients are similar to those obtained in comparable study groups in North America (

33–

35,

38) and Europe (

13,

37). Among patients with Dissociative Experiences Scale scores higher than 30, 81.0% of evaluated patients suffered from a clinically confirmed, chronic, complex dissociative disorder; this finding confirms that high scores on the scale are highly suggestive of a dissociative disorder.

In our study, women had a higher mean Dissociative Experiences Scale score than men. That Dissociative Experiences Scale scores of men and women do not differ in the general population (

27,

39) and among patients with different psychiatric disorders (

35) suggests that women with dissociative symptoms are hospitalized more frequently. Results reported by Chu and Dill (

38) and Latz et al. (

35) support this idea. Because these studies had few (

38) or no (

35) male subjects, their results are not comparable with ours. Some of the previous studies (

40,

41) pointed out that childhood traumata are more common among women.