There are several risk factors for depressive symptoms among men preceding and following the birth of a child. Research on the correlates of men's depressive symptoms following the birth of a child points to similarities with, rather than differences from, the findings for women. Higher rates of depression following the birth of a child have been found for those men who are unemployed, who have less satisfactory and more conflicted relationships with their partners, and who have less emotional and social support from family and friends. However, much of this research has focused on volunteer and selected samples and has not taken family type (stepfamily or traditional family) into account. The current study contributes to this literature by studying levels and correlates of depressive symptoms following the birth of a child in a large, representative community sample of men in different types of families.

RESULTS

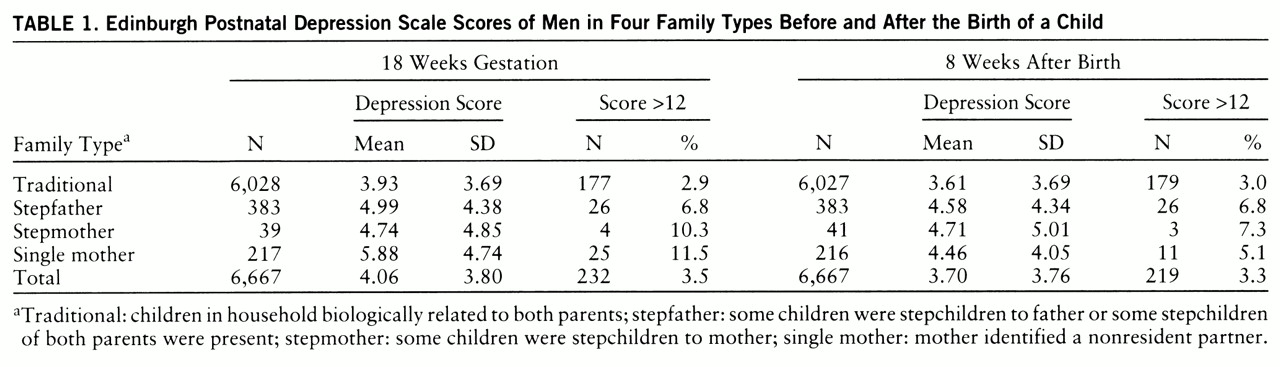

The mean scores reflecting depressive symptoms in the men before and after the birth of the child are shown in

table 1. These means varied significantly by family type before the birth (F=27.59, df=3,6663, p<0.001) and after the birth (F=12.03, df=3,6663, p<0.001, linear regression). A Bonferroni multiple-comparison test revealed that there were significant differences (p<0.05) before and after the child's birth between stepfather families and traditional families as well as between single-mother families and traditional families.

Although the primary analyses focused on the statistical prediction of the continuous Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores, we explored the rates of depression using a threshold score of greater than 12. Using this as our criterion, we estimated the rates of depression before and after the birth of the child (

table 1). These rates varied significantly by family type: men in stepfamilies had more than twice the rates found for men in traditional families before the birth (χ

2=64.89, df=3, p<0.001, Pearson chi-square) and after the birth (χ

2=21.00, df=3, p<0.01, Pearson chi-square).

Men's depressive symptoms were correlated with their partners' depressive symptoms before the birth (r=0.24, df=6223, p<0.001) and following the birth (r=0.26, df=6605, p<0.001). Including maternal depressive symptoms in the linear regression models predicting men's depressive symptoms (both before and after the birth) did not affect the significance of the family type effect. However, there was a significant interaction between maternal depression and type of family before the birth (F=3.14, df=3,6166, p<0.05) and following the birth (F=3.06, df=3,6548, p<0.01). The correlations between mothers' and partners' depressive symptoms in the stepfather families before the birth (r=0.33, df=351, p<0.001) and after the birth (r=0.39, df=377, p<0.001) were higher than for the men in other family types before the birth (traditional families, r=0.23, df=5592, p<0.001; stepmother families, r=–0.02, df=36, n.s.; single-mother families, r=0.26, df=192, p<0.001) and following the birth (traditional families, r=0.25, df=5929, p<0.001; stepmother families, r=0.35, df=40, p<0.05; single-mother families, r=0.22, df=207, p<0.01).

To test whether the effect of family type could be accounted for by other factors, further covariates were added to the regression model predicting depressive symptoms following the birth. Prior to this, we estimated the univariate associations between the covariates (F tests and correlations) and postnatal depressive symptoms. Higher levels of depressive symptoms following the birth were associated with lower educational qualifications (F=4.17, df=3,6522, p<0.01), living in rented housing (F=25.92, df=2,6640, p<0.001) and low-income housing and apartments (F=8.48, df=4,6623, p<0.001), more crowding (F=39.12, df=1,6579, p<0.001), older age (r=0.03, df=6789, p<0.05), unemployment (F=55.97, df=1,6893, p<0.001), less social support (r=–0.22, df=6791, p<0.001), smaller social networks (r=–0.13, df=6845, p<0.001), lower partnership affection (r=0.19, df=5896, p<0.001), higher partnership aggression (r=–0.20, df=5944, p<0.001), more stressful life events (r=0.28, df=6415, p<0.001), and more frequent changes in romantic relationships (F=7.03, df=2,5354, p<0.001).

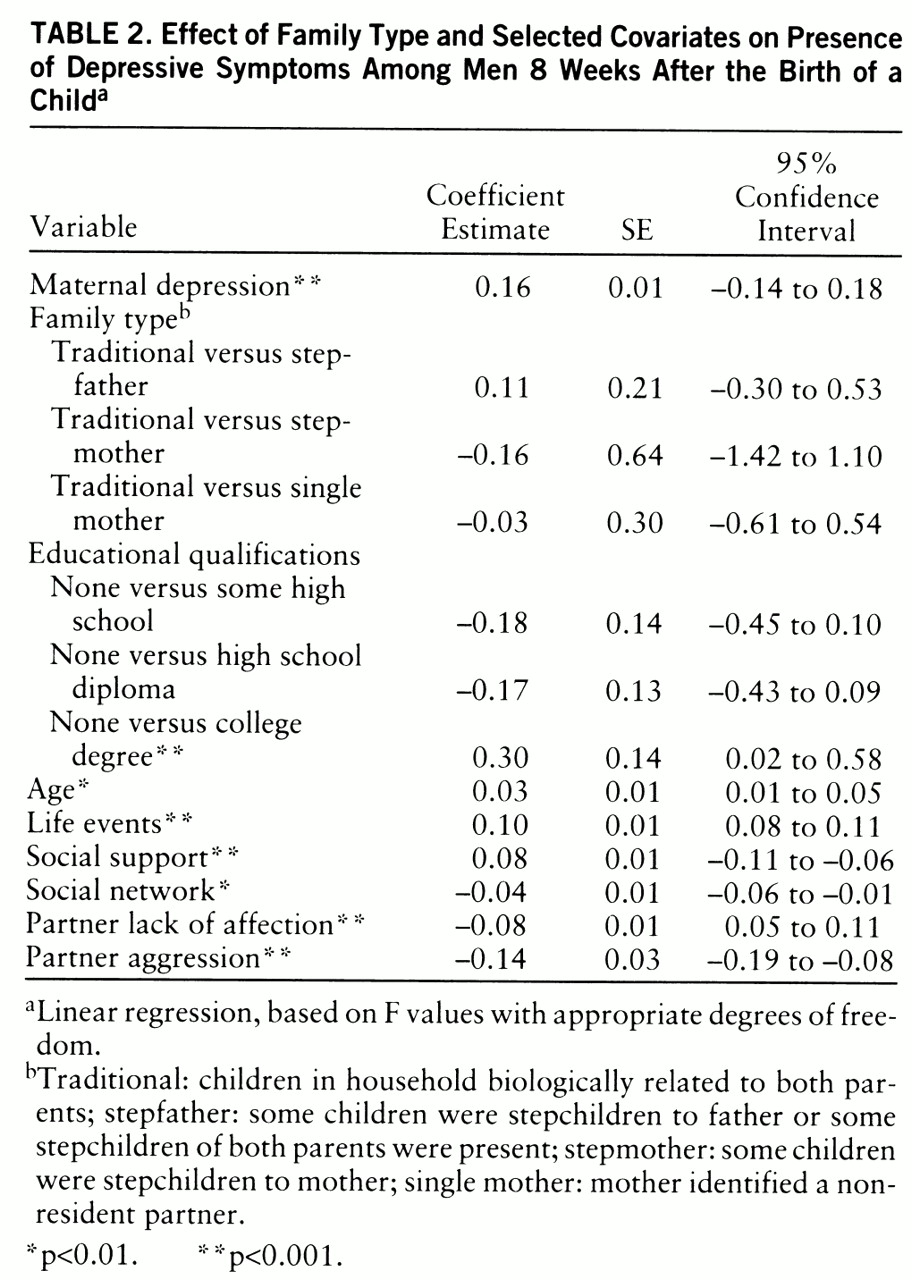

The final model included only those covariates which were significant in the full regression equation: a categorical measure of educational qualifications (none, some high school, high school diploma, and college degree), age, weighted life events, social support and social network, and aggression and lack of affection in the partnership. The parameter estimates and standard errors for this model are shown in

table 2.

When the selected covariates were included in the final model, family type was no longer a significant predictor of depression following the child's birth. A higher depression score was related to being older, having less education, experiencing more stressful life events, receiving less social support, having smaller social networks, and having more aggressive and less affectionate partner relationships.

The selected covariates in the final model explained the variance that was due to stepfather status. To indicate which of these selected covariates were potential mediators between stepfather status and depression, the difference in means of the selected continuous measures for the traditional and stepfather families was tested by using an unpaired t test. For the selected categorical measures, the difference in rates between the two family types was tested by using a Pearson chi-square test.

The measures that were associated with stepfather status and, therefore, were statistical mediators between stepfather status and depressive symptoms included educational qualifications (χ2=54.50, df=3, p<0.01), number of life events (t=7.79, df=6042, p<0.01), social support (t=–6.37, df=6435, p<0.01), social network (t=–8.05, df=6486, p<0.01), and aggression (t=2.31, df=5768, p=0.02). The men in traditional families had more education (21% with no qualifications and 24% with college degrees), fewer life events (mean=8.4, SD=7.5), higher social support (mean=18.1, SD=4.7), larger social networks (mean=22.5, SD=3.9), and less aggression in their partnerships (mean=10.0, SD=1.8) than men in stepfather families, who had less education (36% with no qualifications and 11% with college degrees), more life events (mean=11.7, SD=9.3), less social support (mean=16.5, SD=5.2), smaller social networks (mean=20.9, SD=4.6), and more aggression in the partnership (mean=9.7, SD=2.0). Age and lack of affection toward the partner were unrelated to stepfather status, which rules out their roles as statistical mediators of the effect of stepfather status on depressive symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Our first aim in this study was to examine the role of family structure in defining groups of men at risk for depression in a large community sample. Men in stepfamilies and partners of single mothers had higher levels of depressive symptoms than men in traditional families. Based on categorical depression scores (greater than 12 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale), the rates of depression 8 weeks after the birth of a child among men in stepfamilies and single-mother families were similar to the 6-week-postpartum rate reported by Ballard and Davies (

28).

We also found that the relation between depressive symptoms and family status was entirely mediated by six risk factors. Stepfathers' higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with higher rates of depression among their partners, less education, more life events, less social support, smaller social networks, and more aggression within their partnerships. These correlates are consistent with those reported in the literature for women (

20) and their male partners (

28). Because these data are correlational and the mediators are self-reported, these links cannot be considered causal, and shared method variance could account for some of the overlapping variance.

Four issues are raised by these findings. First, level of women's depressive symptoms was the strongest correlate of men's depressive symptoms. Although we cannot draw causal inferences from these correlational data, a number of different processes might be implicated here. It could be that each partner's psychosocial state directly influences the other's—that living with a depressed person has a depressing effect. It could also be that common causal factors outside the family, such as social stresses, contribute to the depressive symptoms of both men and their partners. Interestingly, the covariates considered in this study did not mediate the relation between the partners' depressive symptoms. Maternal depressive symptoms remained a highly significant predictor of men's depressive symptoms even after the selected covariates (age, education, life events, social support, social network, and affection and aggression within the partnership) had been included in the statistical model. It could also be that men and women who are vulnerable to depression are more likely to form relationships. Whatever the causal patterns, it is clear that beyond the usual social risks for depression, having a depressed partner is an important risk as well.

A second point is that, overall, men's depressive symptoms did not increase following the birth of a child, a finding that has been shown in some of the other studies of selected samples of men (

28). The constellation of events surrounding the birth did not constitute an added risk for the vast majority of these men. It should be emphasized that even in the stepfather families, the child being born was in the very great majority of cases the child of this father. It was his relationships with the older children in the household that were step-relationships.

The third issue concerns the role of socioeconomic circumstances in the etiology of depression. Consistent with findings in other studies (

20,

28,

33), there were associations between socioeconomic factors and depressive symptoms in this study. However, most of the sociodemographic covariates (housing indicators and unemployment) were no longer significant once all of the variables had been considered in a single regression model. Thus, socioeconomic differences between stepfather and traditional families (the former had more disadvantaged circumstances) were not responsible for the higher level of depressive symptoms among stepfathers.

Finally, we add a note of caution. We have stressed that the correlational nature of the data precludes inferences on causal mechanisms. To that caution we should add that one cost of having depression data on such a large sample is that we do not have precise diagnostic information. We lack data on psychiatric history, and we did not have a comparison group of partners of nonpregnant women. Thus, these findings may not generalize to studies that have employed more precise measures of depression in men. In spite of these shortcomings, the findings draw attention to an important set of facts—men in stepfamilies may be at greater risk for depression than those in traditional families, and this risk is closely linked to their partners' depressive symptoms. The risk for children growing up in a family with two depressed parents is not trivial; rather, it deserves further research attention.