Harbingers of depressive personality disorder were present in Hippocrates' melancholic, or “black gall,” temperament described more than 2,000 years ago. This personality type was subsequently characterized by some of the founders of our diagnostic system, including Kraepelin, Kretschmer, and Schneider (

1). Although depressive personality disorder was represented in DSM-II, it was omitted from DSM-III and DSM-III-R. Yet, within the past decade, clinicians with diverse theoretical perspectives, such as Kernberg (

2) and Akiskal (

3), have prompted a reawakening of interest in this putative disorder.

Despite the long history and reliability of depressive personality disorder (

4–

7), it was added to DSM-IV's appendix B (Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study) amid controversy (

8). The main issue was whether it could be differentiated conceptually and empirically from dysthymia, major depression, and other personality disorders (

9). This article addresses those questions.

Depressive personality disorder is defined in DSM-IV as a pervasive pattern of depressive cognitions and behaviors beginning by early adulthood and occurring in a variety of contexts. Because of concern that this disorder would become simply another name for dysthymic disorder or major depression, DSM-IV stipulates that the disorder does not occur exclusively during major depressive episodes nor is it better accounted for by dysthymic disorder. The diagnosis is established by five or more of the following criteria: 1) usual mood is dominated by dejection, gloominess, cheerlessness, joylessness, and unhappiness; 2) self-concept centers around beliefs of inadequacy, worthlessness, and low self-esteem; 3) is critical, blaming, and derogatory toward the self; 4) is brooding and given to worry; 5) is negativistic, critical, and judgmental toward others; 6) is pessimistic; and 7) is prone to feeling guilty or remorseful.

Depressive personality disorder is characterized primarily by a particular constellation of personality traits—many of which are cognitive, intrapsychic, and interpersonal—in contrast to dysthymia's emphasis on somatic symptoms (

8). Available data suggest that depressive personality disorder may be comorbid with axis I mood disorders but that its overlap with them is far from complete (

6,

7,

10). While depressive personality disorder may be distinct from axis I mood disorders, it may nonetheless be related to them as an early-onset, enduring, trait-like variant (

7,

11,

12) that may predispose individuals to the axis I mood disorders. This posited “spectrum relationship,” supported by evidence of a familial relationship between depressive personality disorder and major depression (

7,

12–

14), is similar to the relationship between schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia (

15) as well as the relationship between behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders (

16).

Available studies have several limitations, however. First, except for the DSM-IV Mood Disorders Field Trial, researchers have diagnosed depressive personality disorder by using criteria that, while reliable, lacked systematic probes and an empirically derived cut-off score for the diagnosis. Second, depressive personality disorder, comorbid disorders, and family history have generally not been assessed by independent raters. Finally, not all comorbid personality disorders have been assessed; the incomplete data leave unanswered the question of whether depressive personality disorder overlaps excessively with other personality disorders and, therefore, is a redundant concept.

In the present study, we address these limitations. We characterize and compare subjects with depressive personality disorder to subjects with chronic mild depressive features who do not have depressive personality disorder. We use independent raters to assess all axis II disorders; furthermore, we diagnose depressive personality disorder by using a reliable and valid diagnostic instrument with probes and an empirically derived cut score for the diagnosis (

5). In addition, we explore treatment history, which has not been previously studied. We hypothesized that depressive personality disorder would be comorbid with, but not completely subsumed by, dysthymia, major depression, and other personality disorders. We also hypothesized that 1) relatives of probands with depressive personality disorder would have a higher rate of axis I mood disorders than relatives of comparison subjects and 2) subjects with depressive personality disorder would have received more psychotherapy than the comparison group because of the chronic, trait-like nature of their depressive features.

METHOD

Subjects

We recruited 54 subjects by asking clinicians at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., for referrals of individuals with possible depressive personality disorder (N=24) and by advertising in a local newspaper for individuals who had been mildly but chronically depressed, gloomy, and unhappy for most of their lives (N=30). Twenty-nine subjects (54%) were outpatients; the remaining 25 (46%) were currently receiving no psychiatric treatment. Exclusion criteria were a current organic disorder, current psychosis, a current or chronic substance use disorder, and current major depression of more than 2 years' duration. We excluded individuals with current major depression of more than 2 years because of the difficulty of assessing personality traits in such subjects. We included, however, individuals with current major depression of less than 2 years' duration because several of our study hypotheses involved major depression. After presenting a complete description of the study to the subjects, we obtained written informed consent.

Assessments

Three psychiatrists, all blind to ratings obtained by the other two, interviewed each subject. The first interviewer administered the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality, a reliable and valid 30-item semistructured instrument that establishes the diagnosis of depressive personality disorder (

5). The disorder is diagnosed only if the traits are characteristic of a person's long-term personality (i.e., present since adolescence or early adulthood) and clearly present outside of major depressive episodes. This instrument includes the DSM-IV criteria and additional items from the depressive personality literature, such as introverted, unassertive/passive, self-denying, and difficulty expressing anger (

1).

The second rater administered three instruments: 1) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (

17) to assess axis I disorders; 2) the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders, Revised (

18), a reliable semistructured instrument that assesses DSM-III-R axis II and appendix disorders; and 3) the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

19) to assess the severity of current depressive symptoms. An axis II assessment was not completed for one subject.

The second rater also assessed treatment history. Treatments evaluated were medications (antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and others), individual psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, couples therapy, and group therapy. Information was obtained on type, number, duration, and efficacy of treatments. In efficacy evaluations, only medication trials that were judged adequate in dose and duration, on the basis of a semistructured assessment instrument (A.A. Nierenberg, personal communication), were included. Treatment data are missing for several subjects.

The third rater administered the Family History Questionnaire, a reliable semistructured instrument to assess DSM-III-R axis I disorders in relatives (

20). This information was obtained from 51 subjects for 236 first-degree relatives (N=127 for the depressive personality group and N=109 for the comparison group).

We completed follow-up interviews with the 45 subjects who agreed to be reinterviewed 1 year after the baseline assessment. The Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality, the SCID, and the 24-item Hamilton depression scale were administered by the second rater, who had been responsible for the SCID and Hamilton depression scale, but not the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality, at baseline. Consequently, this rater was blind to baseline ratings on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality.

Statistical Analysis

We performed data analysis by using SPSS for Windows, version 6.12, with an additional “exact test” module for Fisher's exact test r×c tables. All statistical tests were triple-checked with SigmaStat 2.0 and Statistica 5.1. We compared the 30 subjects with depressive personality disorder to the 24 subjects without depressive personality disorder in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, axis I and axis II disorders, family history, treatment history, and other variables. We tested between-group differences by using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, using 2×k contingency tables (Freeman-Halton test) for the family history data and 2×2 tables for other analyses. We used Student's t tests for continuous variables. Although we have reported all significant differences (p<0.05, two-tailed), one should exercise caution in interpreting these values because we performed multiple comparisons; some findings, particularly those of only modest significance, may represent chance associations. In addition, we examined the relationship between major depression (present or absent) and depressive personality disorder (present or absent) at baseline and again at follow-up.

RESULTS

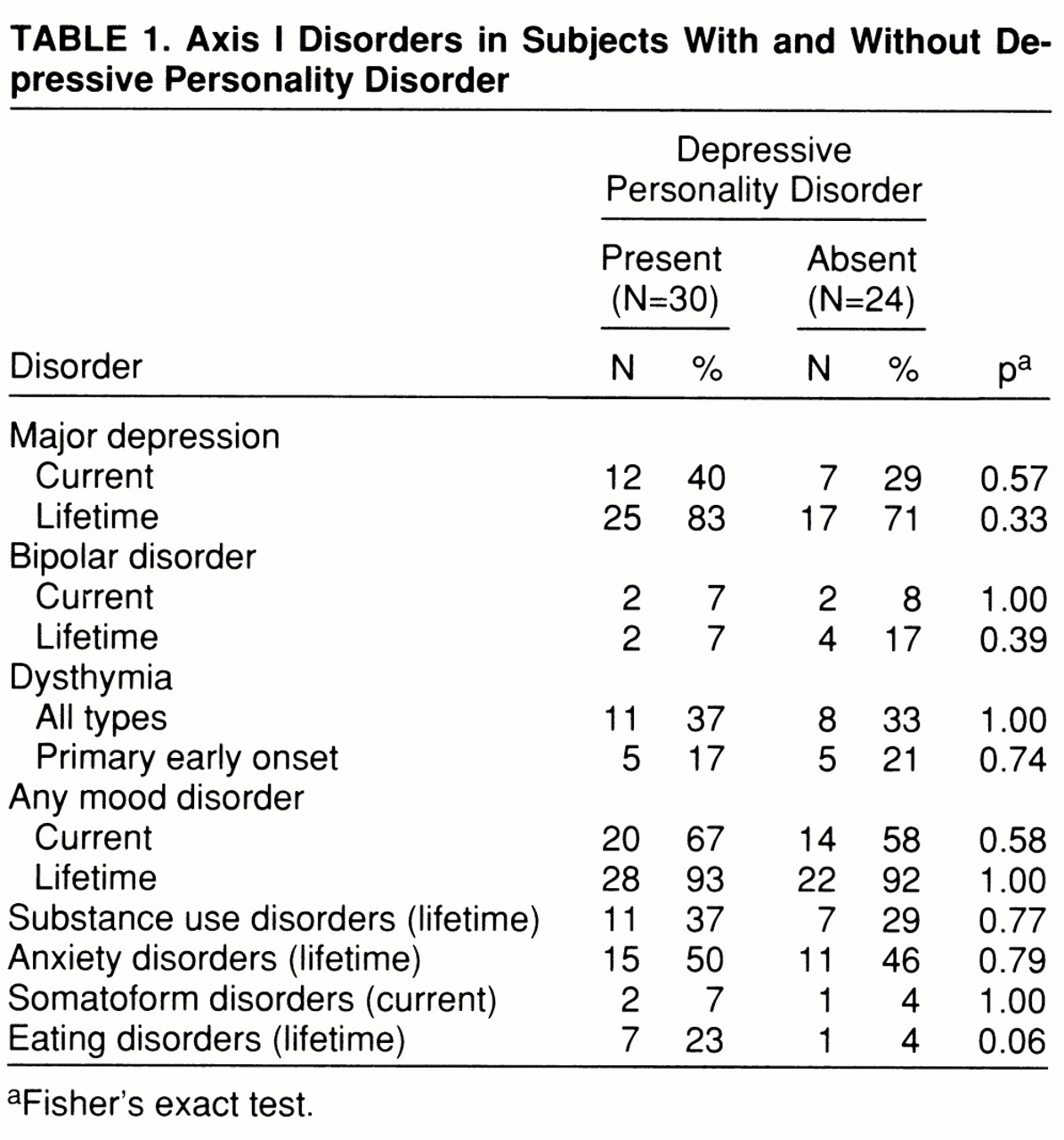

The 30 subjects with depressive personality disorder did not differ significantly from the 24 subjects without depressive personality disorder in terms of sociodemographic characteristics. The two groups were similar in age and sex ratio (mean age=38.0 years [SD=9.9], 50% [N=15] female, and mean age=44.1 years [SD=13.1], 71% [N=17] female, respectively), as well as marital status, education, and employment status. The two groups did not differ significantly in rates of comorbid mood disorder or any other axis I disorder (

table 1). Depressive personality disorder and dysthymia co-occurred in some subjects. Of subjects with depressive personality disorder, 37% also met criteria for dysthymia, and 17% met criteria for the early-onset type of dysthymia. Conversely, 62% of subjects with dysthymia and 56% of those with the early-onset type of dysthymia also met criteria for depressive personality disorder.

Mean Hamilton depression scale scores were in the dysthymic range for both groups and did not differ significantly between the subjects with depressive personality disorder (mean=15.4, SD=8.7) and those without depressive personality disorder (mean=13.4, SD=8.5). Global Assessment of Functioning scores were also similar in the two groups for subjects with depressive personality disorder (mean=60.6, SD=10.8) and those without depressive personality disorder (mean=62.8, SD=17.5).

The rates of cluster A and cluster B personality disorders were relatively low and did not differ significantly between the two groups. Of subjects with depressive personality disorder, 13% (N=4) had a comorbid odd cluster disorder, and 20% (N=6) had a comorbid dramatic cluster disorder; the mood disorder comparison group had 4% (N=1) in each cluster. However, subjects with depressive personality disorder were significantly more likely than those without depressive personality disorder to have avoidant personality disorder (33% [N=10] versus 9% [N=2], p<0.05) and any anxious cluster disorder (53% [N=16] versus 17% [N=4], p=0.01). The former were also more likely than the latter to meet criteria for any axis II disorder (60% [N=18] versus 22% [N=5], p=0.01). However, they were not more likely to meet criteria for self-defeating or any other personality disorder.

Contrary to our hypothesis, rates of lifetime mood disorder in first-degree relatives of subjects with depressive personality disorder were not higher than in relatives of subjects without depressive personality disorder. Of the relatives of subjects with depressive personality disorder, 9% (N=12) had major depression, 9% (N=12) had dysthymia, and 14% (N=18) had any mood disorder; among relatives of the mood disorder group, the rates were 17% (N=18), 14% (N=15), and 22% (N=24) for those respective disorders. The two groups of first-degree relatives did not significantly differ in rates of other axis I disorders.

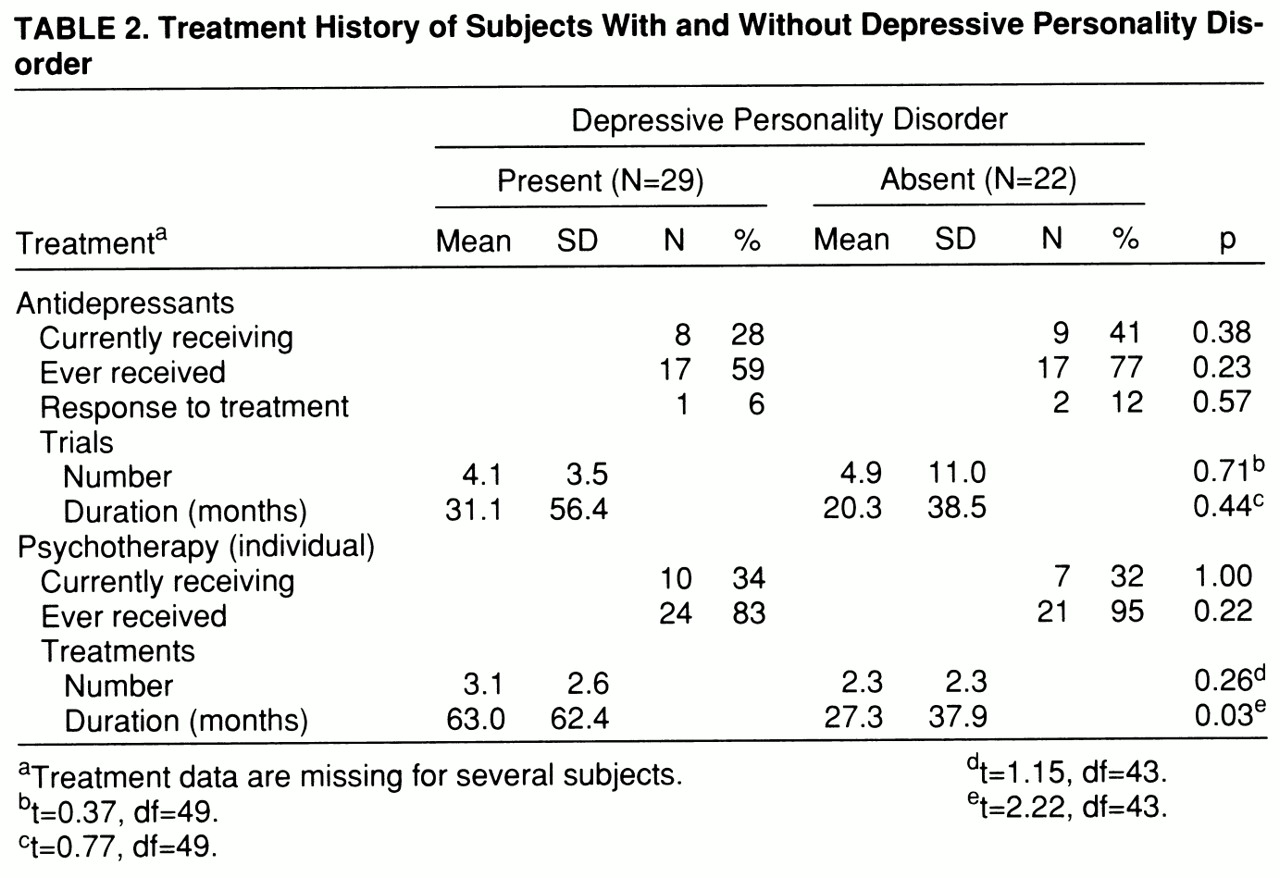

The two groups also did not differ in antidepressant medication or individual psychotherapy received (

table 2), or other medications or therapies received, with one exception: subjects with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater mean duration of individual psychotherapy than did the comparison group. The two groups did not differ in terms of treatment efficacy. The response rate of long-standing depressive features to antidepressants was notably low in both groups, with only one subject (6%) with depressive personality disorder and two (12%) without depressive personality disorder reporting moderate or good response to at least one adequate antidepressant trial.

Regarding the stability of the depressive personality diagnosis over the 1-year follow-up period (with different raters at baseline and follow-up), we obtained a kappa of 0.55 for diagnostic placement and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.62 for the total score on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality.

With respect to the relationship between major depression (present or absent) and depressive personality disorder (present or absent) at baseline and follow-up, change in one of those diagnoses was generally not accompanied by change in the other. Eight subjects had major depression at baseline but not at follow-up; none of them changed in terms of depressive personality diagnosis (five had depressive personality disorder at both baseline and follow-up, and three had the disorder at neither baseline nor follow-up). Another seven subjects did not have major depression at baseline but did at follow-up; only two of these had a change in depressive personality diagnosis (one had the diagnosis at baseline but not at follow-up; the other did not have the diagnosis at baseline but did at follow-up).

Six subjects met criteria for depressive personality disorder at baseline but not at follow-up; five of them did not have major depression at baseline or at follow-up; one did not have major depression at baseline but did at follow-up. Three subjects did not have depressive personality disorder at baseline but did at follow-up; none had current major depression at baseline, and one did at follow-up.

Change scores on the Hamilton depression scale and Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality Disorder between baseline and follow-up, however, were significantly correlated (N=40, r=0.42, p<0.01). Scores were not significantly correlated at baseline (N=43, r=0.27, p=0.06) but were at follow-up (N=42, r=0.39, p<0.01).

Scores on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality Disorder did not differ significantly between subjects with and those without current major depression (mean=41.2, SD=11.2, and mean=37.6, SD=12.8, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that although depressive personality disorder can be comorbid with its near-neighbor axis I and axis II disorders, it can also occur in their absence and is distinct from them. Our findings that 1) nearly two-thirds of subjects with depressive personality disorder did not have dysthymia, 2) 83% did not have early-onset dysthymia (the disorder most similar to depressive personality disorder), and 3) 60% did not have current major depression are similar to the findings of other investigators (

6) and to the results of the DSM-IV Mood Disorder Field Trial (

10). Klein and Miller's nonclinical sample of subjects with depressive personality disorder (

7) had an even lower frequency of lifetime axis I mood disorders. Similarly, our finding that 40% of subjects with depressive personality disorder had no other personality disorder indicates that overlap between depressive personality disorder and other personality disorders is incomplete. This result confirms previous findings of little overlap with borderline or schizotypal personality disorders (

6,

7) and extends these findings by demonstrating that the overlap remains incomplete when all axis II disorders are assessed. It is interesting that the cluster C (anxious) disorders were most frequently comorbid, consistent with the neurotic-level conflicts and defenses noted to characterize depressive personality disorder (

21).

A somewhat surprising finding was our failure to confirm reports (

12–

14) of a familial relationship between depressive personality disorder and axis I mood disorders, which has previously been demonstrated by 1) higher rates of depressive personality disorder in offspring of depressed subjects than in offspring of comparison subjects (

13) and 2) higher rates of major mood disorder in relatives of depressive personality probands than in relatives of comparison probands (

7,

14). However, in another study conducted in a setting more similar to ours, a higher proportion of relatives of depressive personality probands (compared to mood disorder probands) had been hospitalized for a mood disorder but did not have a higher rate of nonbipolar depression (

6). While the fact that our assessments of relatives were blind to proband diagnoses adds credibility to our findings, our results are limited by use of the family history method, which tends to underdiagnose disorders in relatives. In addition, the high rate of axis I mood disorders in both study groups could have obscured differences in mood disorder rates in relatives.

Our results demonstrating relatively good stability of depressive personality disorder over 1 year are similar to those of a previous study over 6 months (

6); they probably represent a lower-bound estimate of stability, given our use of different raters at baseline and follow-up. Of additional significance is the relative independence of changes in depressive personality disorder and major depression diagnoses between baseline and follow-up. However, the significant baseline correlation between change scores on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality Disorder and the Hamilton depression scale, along with their significant correlation at follow-up, suggests that depressed mood may confound assessment of depressive personality traits. The fact that depressive personality disorder and depression were assessed at follow-up by the same rater may have contributed to the correlation through a halo effect.

The relatively low scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale indicate that persons with depressive personality disorder experience impairment, although the degree to which the disorder contributed to impairment is unclear. Other investigators (

7,

10) found similar levels of impairment; in addition, they found that subjects with depressive personality were more impaired than comparison groups. In the DSM-IV Mood Disorders Field Trial, individuals with depressive personality disorder scored significantly lower than mood disorder comparison subjects on the mental health and health perception scales of the Medical Outcome Study Short-Form General Health Survey, on overall adjustment, and on five of nine scales of the Social Adjustment Scale Self-Report (

10). Klein and Miller found that subjects with depressive personality disorder had lower scores on the Global Assessment Scale than those without the disorder, even in the absence of a history of mood disorder (

7). This documentation of impairment suggests that depressive personality disorder does not consist simply of normal personality traits; it may, nonetheless, be on a continuum with normal personality traits (e.g., negative affectivity or neuroticism) that can, at their extreme, become dysfunctional.

Although we did not confirm previous findings (

7) that individuals with depressive personality disorder are more likely than those without the disorder to seek psychotherapy (most subjects in both groups obtained such treatment), we did find that those with depressive personality disorder had received psychotherapy longer than those without the disorder. It is unclear whether the very low response rate of long-standing depressive features to antidepressants indicates that depressive personality disorder is generally unresponsive to antidepressants or that we studied treatment-resistant subjects. The latter explanation seems likely, given that, at the very least, depressive features of our mood disorder comparison group would be expected to improve with adequate antidepressant treatment in a high percentage of cases; we probably selected a treatment-resistant group by recruiting subjects with chronic depressive features, nearly half of whom were in treatment at a tertiary care center. Whether personality disorders respond to antidepressants is an interesting and important issue that has been discussed in the popular press (

22). Does depressive personality disorder have a sufficient neurobiologic basis to be ameliorated by pharmacotherapy? Or is it better understood as a form of depressive character that is more effectively treated by psychotherapy? Or might both treatments be effective? The answers await prospective treatment studies.

Our diagnostic system is in flux, and there is ongoing need to evaluate and improve it. DSM-IV appendix disorders are in particular need of investigation. Our findings confirm those of previous investigators that the depressive personality disorder diagnosis identifies individuals with a relatively stable condition, involving impairment, that is not otherwise covered by DSM-IV mood or personality disorders. Our results also highlight the need for additional studies, including family history and treatment studies, that will further clarify the meaning of this construct—in particular, its relationship to axis I mood disorders. Such studies are also needed to shed light on the question of whether depressive personality disorder reflects a temperament with a heritable relationship to depressive disorders, a dysfunctional character type, or both.