The appearance or worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms during group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infections may result from a single neuroimmunological dysfunction mediated by antineuronal antibodies (

1,

2). In Sydenham's chorea, they presumably cross-react with epitopes on basal ganglia neurons, resulting in adventitious movements (

3). Obsessive-compulsive symptoms have been retrospectively associated with Sydenham's chorea but not with rheumatic fever without chorea (

2,

4,

5).

We report a prospective study of the incidence and course of obsessive-compulsive symptoms or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and other psychiatric conditions in pediatric outpatients with rheumatic fever, with and without Sydenham's chorea, assessed from an early stage of rheumatic fever.

METHOD

Fifty outpatients from pediatric clinics of the University of São Paulo Medical Center who met the criteria for rheumatic fever (

6) of less than 60 days' duration were included in this study over 4 years. The study group included 30 patients with Sydenham's chorea (17 girls) and 20 without Sydenham's chorea (10 girls). Their mean ages at the onset of rheumatic fever were 10.5 years (SD=2.3, range=5–17) and 9.5 years (SD=3.1, range=4–16), respectively.

Patients with histories of psychiatric disorders, other causes of chorea, or other neurological disorders were excluded. The subjects and parents gave written informed assent and consent, respectively, for participation in this study.

After medical and laboratory evaluations, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) was used to assess current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses according to DSM-III-R. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms were assessed through the 44-item Leyton Obsessional Inventory—Child Version, divided into scores for resistance and interference (

7), and the National Institute of Mental Health Global Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (

8). Since the average duration of Sydenham's chorea is 4–6 months (

1,

2), the patients were assessed at three time points: during the first 2 months after the onset of rheumatic fever (time 1), during month 3 or 4 (time 2), and during month 5 or 6 (time 3). In each case, the assessment was based on interviews with the patient and one or both parents.

Because of missing data and unequal variances (significant Bartlett's test), unbalanced repeated measurement models were used (

9). Presence or absence of chorea (“chorea”) was used as a between-subjects factor, time of measurement (“time”) was used as a within-subjects factor with the correlation between measures for the same person taken into account, and the two-way interaction (chorea by time) was used as a dependent variable (BMDP-5V statistical software, 1990). Given the highly skewed distributions, squared root was used to fit the model. The Wald test was employed to assess the significance of variables in the models. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the resistance and interference scores of the two groups at each time. Two-tailed chi-square or Fisher exact tests were used to contrast psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms of inattention/hyperactivity in the two groups.

No specific treatment for obsessive-compulsive symptoms was administered during the study. Prophylactic intramuscular penicillin G benzathine was provided twice a month to all patients from the onset of the disease.

RESULTS

All patients had been free from obsessive-compulsive symptoms before the onset of rheumatic fever. Of the 30 patients with Sydenham's chorea, 21 (70.0%) had an abrupt onset of obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the illness. The onset and peak of obsessive-compulsive symptoms occurred during the first 2 months of rheumatic fever (time 1) for all 21 patients. Six (28.6%) of the 21 developed obsessive-compulsive symptoms before the onset of Sydenham's chorea, seven (33.3%) developed them concomitantly, and eight (38.1%) developed obsessive-compulsive symptoms after the movements had begun. Five (16.7%) of the 30 patients with chorea met criteria for OCD and were so diagnosed only at time 1. At time 2 (month 3 or 4) and time 3 (month 5 or 6), the symptoms were milder, waning over time: 10 patients (47.6%) at time 2 and six patients (28.6%) at time 3 still had obsessive-compulsive symptoms. No patient without chorea had clear-cut obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the period of evaluation.

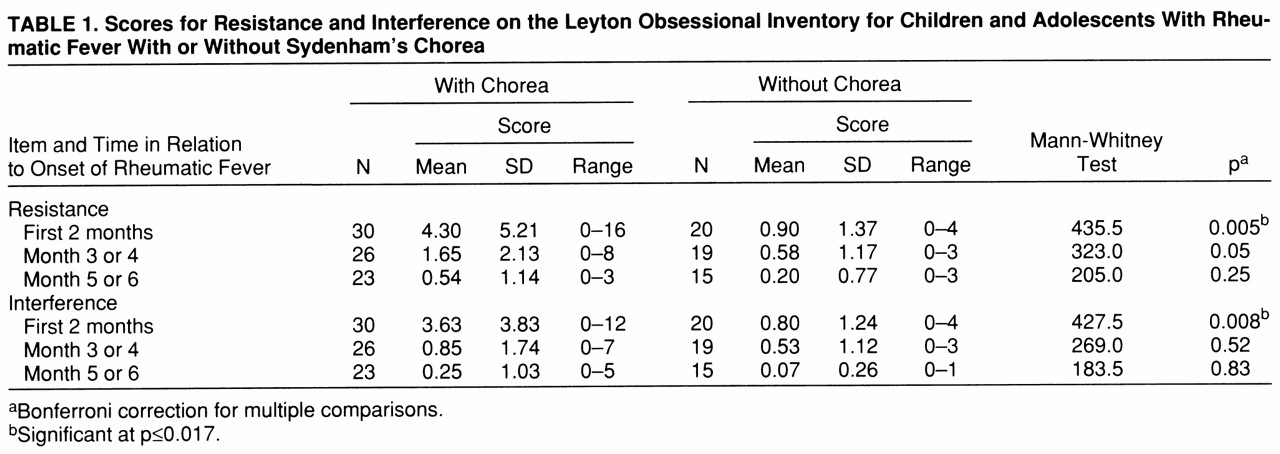

In the analysis of the scores for resistance from the Leyton Obsessional Inventory, the Wald test results were significant for chorea (χ2=9.63, df=1, p=0.002) and time (χ2=22.27, df=2, pχ2=0.001) and nearly significant for the chorea-by-time interaction (χ2=5.74, df=2, p=0.06). For the interference scores, the Wald test results were significant for all three variables: chorea (χ2=4.25, df=1, p=0.04), time (χ2=31.03, df=2, p≤0.001), and chorea by time (χ2=9.88, df=2, p=0.007). “Chorea” indicates the difference in scores between the two groups, “time” shows that the scores changed over time, and “chorea by time” indicates that the time course of the scores differed between groups.

The resistance and interference scores were significantly higher in the patients with chorea than in the group without chorea at time 1 but not at time 2 or time 3 (Mann-Whitney tests) (

table 1).

The frequencies of psychiatric diagnoses in the two groups were not statistically different (data not shown). The appearance of clinically significant inattention/hyperactivity (eight or more symptoms on the K-SADS) was concomitant with the onset of Sydenham's chorea in 11 children (36.7%). Ten of them (33.3%) had concurrent onset of obsessive-compulsive symptoms or OCD. As for the group without chorea, two children (10.0%) had relevant inattention/hyperactivity symptoms (odds ratio=5.21, confidence interval=0.91–53.19; χ2=3.16, df=1, p=0.08).

DISCUSSION

This prospective study shows that the appearance and peak of obsessive-compulsive symptoms or OCD occur less than 2 months after the onset of rheumatic fever. As the symptoms subsided within 4 months in most patients, early assessments are necessary for accurate evaluation. The onset of obsessive-compulsive phenomena occurred either at the same time as or after the onset of Sydenham's chorea in more than 70% of the patients. Therefore, they did not predict development of Sydenham's chorea. As previously reported (

5), the clinical presentation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in such patients is similar to that found in children and adults with OCD.

The severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in this study group was milder than that seen in previous investigations. This may reflect a referral bias, differences in disease severity, or both. Indeed, the present patient group might have been less impaired since it was drawn from a general medical center, while the patients in previous studies (

4,

5) were referred to a child psychiatry unit.

Along with the recent association between a trait marker for rheumatic fever susceptibility (D8/17) and some forms of childhood-onset OCD and Tourette's syndrome (

10,

11), the present results support an association between Sydenham's chorea and obsessive-compulsive symptoms or OCD, as well as the suggestion of Swedo et al. (

4,

5) that similar mechanisms involving a dysfunction of the basal ganglia may account for both disorders.

Although only one patient met the criteria for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, because this diagnosis can be made only for children younger than 7 years old at the onset of the disease or with symptoms of at least 6 months' duration, the concomitant onset of obsessive-compulsive symptoms or OCD and clinically significant inattention/hyperactivity in 10 patients with Sydenham's chorea is noteworthy and is in keeping with the proposal for a single neuroimmunological dysfunction.

In order to verify and support these interpretations, titers of antineuronal antibodies for these patients are currently being assayed.