Some epidemiologic research suggests that adults with a lifetime history of panic disorder might be at greater risk for suicide attempts

(1). The present investigation looks for evidence of this association earlier in the life span, seeking to estimate the strength of association between a lifetime history of panic attacks and suicide attempts in a community sample of adolescents.

Weissman et al.

(1), analyzing lifetime history data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study, reported that “both panic attacks and panic disorder, as compared with other psychiatric disorders, are associated with increase in the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts” (p. 1212). Compared with subjects who had no psychiatric disorders, subjects with panic disorder were 17–18 times more likely to report having made one or more suicide attempts. Compared with subjects who had any psychiatric disorder, the odds ratio—1.67—was much lower.

Hornig and McNally

(2) reanalyzed the same ECA lifetime history data, using different methods, and reached the opposite conclusion, i.e., that panic disorder was not associated with a greater risk of suicide attempts. Their analysis differed from that of Weissman et al.

(1) in two ways. First, Weissman et al. controlled for psychiatric disorders one at a time, but Hornig and McNally

(2) controlled for them in aggregate. Second, Hornig and McNally controlled for schizophrenia, a disorder associated with a greater suicide risk

(3).

Newer, prospectively gathered ECA data and other epidemiologic evidence suggest that major depression, alcohol dependence, and cocaine use are associated with a greater risk of suicide attempts and panic attacks during follow-up observation intervals

(4,

5). The co-occurrence of panic disorder and major depression has been reported in both adult

(6) and adolescent

(7) samples. Estimates of comorbidity between panic disorder and depression vary from 20% to 75%

(8). Thus, in research on panic and suicide it is essential to adjust for the presence of major depression and drug use.

Most clinical studies do not find an association between panic disorder and suicide attempts in the absence of comorbid disorders such as affective disorders, substance use disorders, and personality disorders

(9–

12). Warshaw et al.

(12) reported on a naturalistic prospective study of 527 patients recruited in clinics and mental hospitals. In their study, almost all of the suicide attempts among patients with panic disorder were reported by individuals who had a co-occurring depression, although not necessarily major depression.

This disparity of results, with some studies supporting and others refuting the association of panic attacks (or panic disorder) and greater suicide risk, may reflect differences in the type of subjects investigated (population-based and clinical samples), the severity of comorbidity, and the amount of information available. Detailed information regarding psychosocial factors, mild disorders (e.g., dysthymia), and personality disorders is less likely to be gathered in epidemiologic studies

(12).

The lifetime prevalence of panic disorder in adult populations is estimated to be 1.6%–2.0%

(13). Data on panic disorder and panic attacks among adolescents stem from small epidemiologic studies and clinical reports, reviewed by Moreau and Weissman

(14) and Ollendick et al.

(15). Although panic disorder is infrequent in mid-adolescence

(16), panic attacks are not. For example, in a study of 95 students whose mean age was 14.5 years, the lifetime prevalence of at least one panic attack approached 12%

(17). Other population-based studies have reported a higher prevalence of panic attacks among adolescents

(7,

18,

19). Prevalence figures are hard to compare because the age range of the adolescents sampled and the ascertainment of panic attacks have differed from one study to another.

With some notable exceptions

(20–

26), studies of suicide attempts among adolescents have relied on clinical samples (e.g., references

27–

29). It is unclear to what extent findings from clinical samples generalize to community samples. The lifetime prevalence of attempts reported in community studies has ranged from 3.5% to 9% and tends to be higher for self-report by high school students on anonymous surveys than for structured interviews

(26,

30). Little is known about the possible association between panic attacks and suicide attempts among adolescents in community settings. With few exceptions

(26,

31), this association has received little attention. The present investigation explored this hypothesized association in a population-based study of adolescents.

METHOD

This investigation represents a cross-sectional study of the association between a lifetime history of panic attacks and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a community sample of adolescents, most of whom were 13–14 years old at the time of assessment.

Sample

This study population consists of students in an urban public school system located in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Two successive cohorts of first graders were recruited beginning in 1985 (N=2,311). The sample was drawn from 43 classrooms located in 19 public elementary schools in five city areas, each chosen to reflect different socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Yearly assessments of all students remaining in the public school system were conducted between 1989 and 1994. At baseline, the 2,311 students were evenly divided between boys and girls. Seventy-five percent were African American, and the mean age was 6 years. Over time, as a disproportionate number of white families transferred their children to other school systems, a preponderance of African American students emerged

(32). Detailed descriptions of the study have been published elsewhere

(32,

33).

For the purpose of this investigation, our sample consisted of 1,580 students interviewed in 1993–1994, when their panic attacks and suicide-related behaviors were first assessed. Of the 1,580 students, 767 were boys and 813 girls. Two hundred ninety-three were Caucasian and 1,287 non-Caucasian (mostly African American). Written informed consent was obtained from parents of participating students. Verbal assent was obtained from all participating adolescents.

Study Assessments

Lifetime history of at least one panic attack was considered present when students answered affirmatively to the question, “Have you ever in your life had a spell or attack when all of a sudden you felt frightened, anxious, or very uneasy in situations when most people would not be afraid or anxious?” This question is from the National Comorbidity Survey

(34).

An adaptation of the depression section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used to assess major depression. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview is a standardized, comprehensive diagnostic interview designed according to the definitions of the diagnostic criteria for research of ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. In adult samples, both test-retest and interrater reliability studies of this instrument have confirmed good to excellent kappa coefficients for most diagnostic sections

(35).

Lifetime history of suicide attempts and/or suicidal ideation was ascertained through an amended version of the relevant Composite International Diagnostic Interview questions. The following two questions were used to ascertain the presence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: “Have you ever felt so low you thought about hurting yourself very very badly, on purpose?” and, “Have you ever tried to hurt yourself very very badly, on purpose?”

Information regarding alcohol and drug use was obtained through the same structured interview.

Data Analysis

Chi-square analysis was used as an aid to interpretation of the observed variation in occurrence of suicidal ideation across subgroups of subjects who had no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, subjects with a history of suicidal ideation but no suicide attempts, and subjects with a history of suicide attempts.

We used logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratio of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among subjects with and without a lifetime history of major depression and panic attacks. All estimates of odds ratio were adjusted for demographic variables (sex and race/ethnicity), a lifetime major depression diagnosis, and a lifetime history of alcohol or use of any of four illicit drugs (marijuana, inhalants, crack, or cocaine).

RESULTS

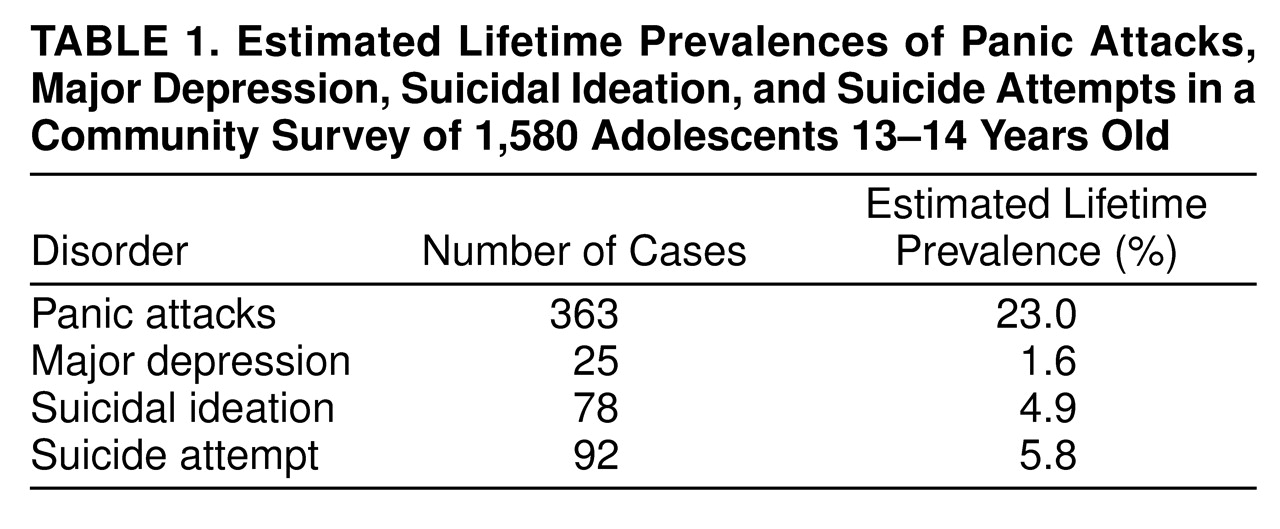

Estimated lifetime prevalence proportions for major depression, panic attacks, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts are shown in

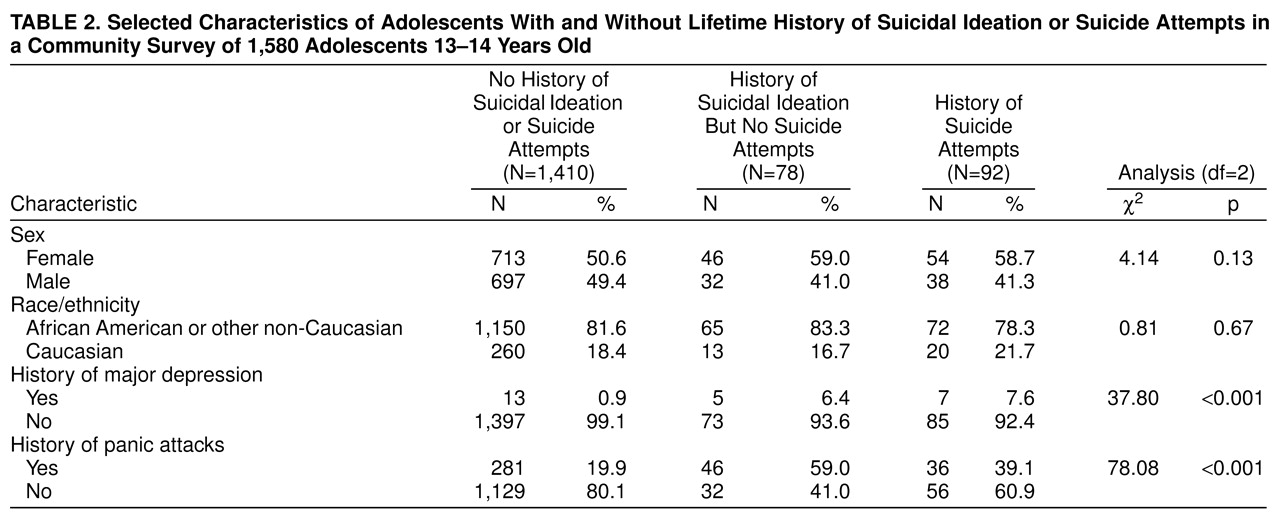

Table 1. Being female and race/ethnicity were not found to be significantly associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in the bivariate analysis (

Table 2). Higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were associated with a lifetime history of panic attacks and major depression (

Table 2).

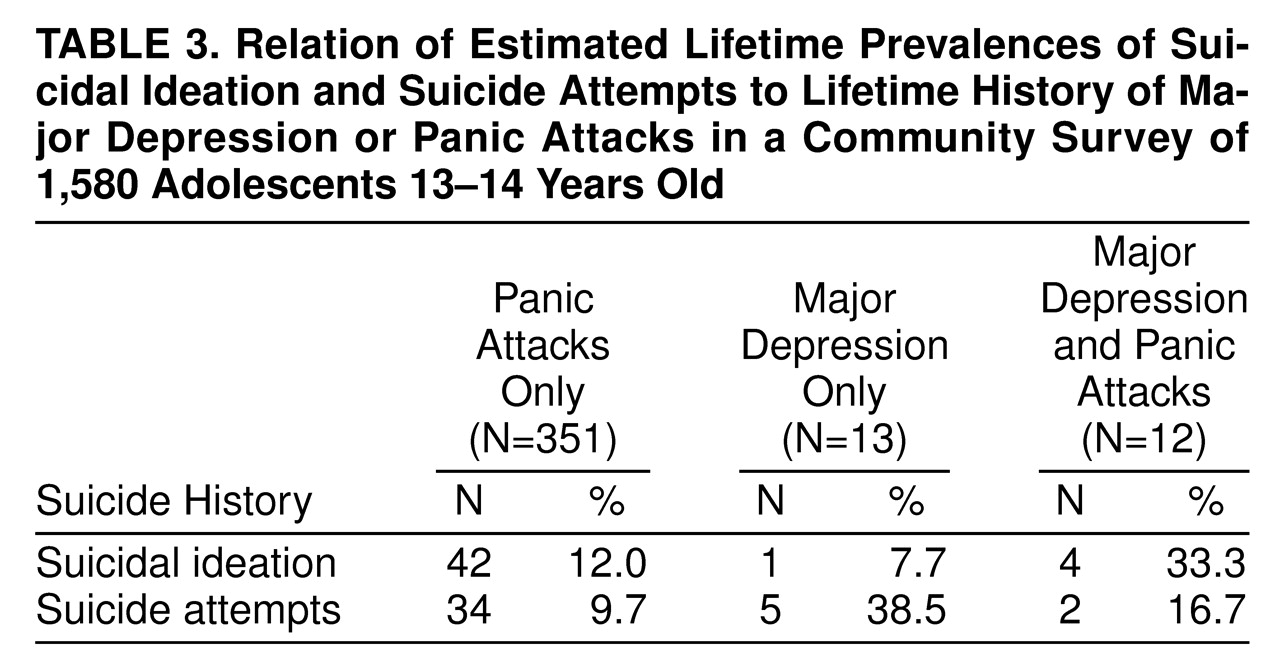

The highest prevalence of suicidal ideation was evident among the 12 adolescents with both major depression and panic attacks (

Table 3). The highest prevalence of suicide attempts was evident among the 13 adolescents with major depression and no panic attacks. These figures should be viewed cautiously because the number of adolescents in each category was small (

Table 3).

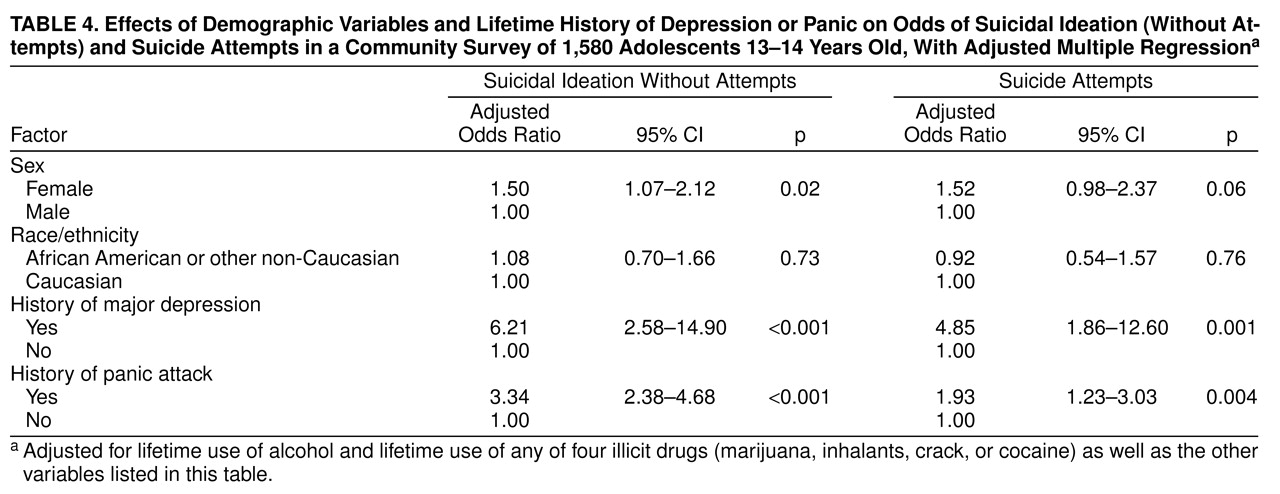

As shown in

Table 4, the logistic regression models revealed that adolescents with history of panic attacks were approximately three times more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and about two times more likely to have made suicide attempts than adolescents without panic attacks. Adolescents with a history of major depression were approximately six times more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and almost five times more likely to have made suicide attempts than adolescents with no history of major depression. These odds were adjusted for demographic variables (sex and race-ethnicity), lifetime history of major depression, history of alcohol use, and the use of any of four illicit drugs (

Table 4).

As a check on the validity of our logistic regression adjustment procedures, we conducted an exploratory search for possible interactions between variables. We did not find that interaction terms improved the fit of the model (alpha=0.10).

DISCUSSION

This study adds new population-based estimates of the association between a lifetime history of panic attacks and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the middle years of adolescence. The logistic regression models indicated that adolescents with a lifetime history of panic attacks were more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and to have made suicide attempts than those without a lifetime history of panic attacks. These findings were obtained with statistical control for demographic variables and other characteristics suspected to affect the occurrence of suicide attempts (e.g., major depression, alcohol use, and illicit drug use).

Although this study has a number of important strengths, including the use of a structured interview and standard diagnostic criteria to ascertain psychiatric disturbances, several limitations are especially noteworthy and deserve comment. A principal limitation of this study is the reliance on cross-sectional lifetime prevalence data, which cannot disentangle the temporal sequences that underlie observed associations between a lifetime history of panic attacks and a history of suicide attempts. Of course, this limitation also applies to the work of Weissman et al.

(1), which remains the most cited published article on this association. Another noteworthy limitation is the lack of control or adjustment for other specific psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders and schizophrenia, which were not assessed in this investigation. However, it should be noted that the prevalence of schizophrenia in early- to mid-adolescence is very low

(36). Last, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview has been validated only in adult populations. Since, according to DSM-IV, adolescent and adult depression present with similar affective, cognitive, motivational, and vegetative symptoms, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview might well be valid among adolescents. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that our adapted question on suicide attempts, designed to be responsive to parental concerns about a sensitive topic, might be broad enough to encompass self-mutilation and self-harming behaviors in general, rather than suicide attempts specifically. This is an issue we are probing in a new follow-up assessment of this sample of adolescents.

Notwithstanding limitations such as these, the association between panic attacks and suicide attempts found in this study parallels the ECA findings reported by Weissman et al.

(1). Anthony and Petronis

(37) expressed concern that reliance on cross-sectional lifetime prevalence ECA data might have created a spurious association between a history of panic attacks and a history of suicide attempts

(1,

38). For this reason, they completed a prospective nested case-control study of 40 ECA respondents who had recently attempted suicide and 160 matched control subjects. Controlling for demographic factors, psychiatric disorders, and drug use, they also found that adults with a lifetime history of panic attacks were at greater risk of suicide attempts

(37). A recent study based on a community sample of children and adolescents aged 9 to 17 years

(31) revealed that panic attacks were significant predictors of suicide risk, after adjustments for relevant psychiatric disorders.

The present study adds to the accumulating evidence of an association between panic attacks and suicide attempts and observes this association in a community sample of adolescents. Two types of studies might confirm that these findings are not the result of a spurious association: 1) conventional epidemiologic case-control studies of adolescents with panic attacks and 2) experimental studies aimed at ascertaining whether preventive treatment of panic attacks might reduce the risk of ensuing suicide attempts.

Panic attacks were ascertained in this investigation in essentially the same manner as in the ECA survey. In all likelihood, some students who reported panic attacks in this study, as well as some adults who reported them in the ECA study, would have met only one DSM-IV criterion for panic attacks. DSM-IV criteria require at least four from a list of 11 symptoms of panic attacks. The list includes symptoms such as palpitations, sweating, and trembling, among others. Had we ascertained the presence of panic attacks using DSM-IV criteria, a group with more severe panic attacks would have been selected. In such a group, the odds of reporting suicide attempts might well have been higher than is conveyed by the estimates reported here.

Andrews and Lewinsohn

(26), analyzing data from their community study of suicide attempts among high school students, found no association between panic disorder and suicide attempts. However, their sample included only 14 adolescents with a lifetime history of panic disorder, which constrained the statistical power of their analysis and the information value of their study. Given the low prevalence of panic disorder among adolescents

(16), it is not surprising that only a relatively small number of students met the criteria for a diagnosis of panic disorder. Focusing on students who reported panic attacks, a more frequent occurrence, has enabled us to base our estimates on more than 300 students with a lifetime history of panic attacks.

This new epidemiologic research extends to adolescents an important finding from adult investigations, i.e., that individuals with panic attacks seem to be more likely to experience suicidal ideation and make suicide attempts than those without panic attacks. Given the current concern about adolescent suicide, research findings that suggest potential risk factors for suicide attempts in this population may contribute to better-informed screening and prevention efforts. Clinicians are well advised to inquire routinely about past suicidal ideation and suicide attempts during the initial interview with adolescents who present with a history of panic attacks and to monitor for emergence of these symptoms during treatment.

Readers also may be interested to know that recent epidemiologic data suggest an increased occurrence of suicidal deaths among African American youths in the United States

(39). Our epidemiologic sample consisted primarily of African American adolescents. Hence, these empirical findings may have some value to clinicians and public health practitioners who seek to curb this trend.