The prevalence of suicide among U.S. women physicians and associated factors, such as psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, has received little recent scientific attention. Published information on these topics has been limited, with much of the work on U.S. physicians having been done a number of years ago, primarily on white, men physicians; additional research has been conducted in other countries. Additionally, there have been no studies of U.S. physician suicide rates stratified by ethnicity, birthplace, or other strata of interest

(1). Despite significant limitations in prior literature, existing work has been used to make broad statements about suicide and psychiatric illness in women physicians

(1,

2).

Suicide has historically accounted for 35% of premature physician deaths

(3) and 3% of U.S. men physician and 6.5% of U.S. women physician deaths (4). These rates appear to be stable; they have prevalences comparable to those of white men above age 25 years

(1,

5). The women physician suicide rate is similar to that of men physicians but is significantly higher than the suicide rate for white women over age 25 years

(1), although the difference in the rate between women physicians and other women has decreased as the suicide rate in women in the general population has increased. Studies have noted a minimal elevation of the suicide risk in U.S. men physicians (odds ratios of <1.0–1.2) compared to that of other U.S. men

(5–

9).

Some of the most persistently cited data about U.S. women physicians concerns their rate of suicide. Studies examining this subject have found a substantially higher rate of suicide for women physicians than for other categories of women (odds ratios as high as 4 have been reported)

(6,

7,

10,

11). However, such studies are based on small numbers (N=17 to 49 suicides). For example, between 1991 and 1993, 48 U.S. physician (and only two women physician) suicides were reported to the American Medical Association (AMA)

(12). These suicide studies are the subject of considerable controversy

(13–

17), given concerns that they suffer from flaws such as small numbers, probable underreporting, poor research designs and sampling procedures, biased assumptions, and flawed statistical analyses

(1,

18).

Research from other areas of the world has, however, demonstrated similar findings, although this research also has had methodological problems (often including inadequate sample sizes), particularly concerning women physicians

(19–

26). Several European investigators have examined suicide rates in women physicians and other women professionals. A Swedish investigation

(27) found that women physicians had a higher suicide rate than did women academicians and the general population, whereas men physicians had a higher rate only when contrasted with other men academicians. A review of suicide in Sweden among health care professionals (1961–1985)

(28) found that women physicians had a high rate of suicide, significantly higher than that of the general female working population.

Lindeman and colleagues

(29) examined existing epidemiologic studies of physician suicide. They found an estimated relative risk in men physicians of 1.1–3.4 compared to that of the general male population and 1.5–3.8 compared to that of other men professionals. Women physicians’ relative risk was 2.5–5.7 compared to that of the general female population and 3.7–4.5 compared to that of other women professionals. The crude suicide mortality rate was about the same for men and women physicians.

Various hypotheses have been advanced to explain physician suicide; suggested contributors include psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, alcoholism, the stresses of practicing medicine, unrealistic expectations, role conflict, the lack of professional support, inadequate psychiatric treatment of physicians, resistance to psychiatric treatment, personality characteristics, and psychosocial factors

(26,

30–

45). Affective disorders, alcoholism, and substance abuse appear to be the most common psychiatric diagnoses among the physicians who commit suicide. There is, however, no systematic information on the distribution of psychiatric illness in physicians who commit suicide; existing studies contain significant methodological and sampling problems

(1). There has been some argument that suicide in physicians is not particularly distinct and should be regarded similarly to the suicide of others in terms of etiologic factors and stressors

(1,

46). Many believe that the practice of medicine poses additional stresses (prejudice and discrimination, the lack of women role models, role conflict, and inadequate family and institutional support) for women

(1,

47–

49). However, no previous systematic investigations have studied whether these stressors are related to the occurrence of psychopathology or suicidal behavior among women physicians

(1). Other studies have documented depressive and other psychiatric manifestations, including nonfatal suicidal behavior in women physicians and other professionals, and speculated that these symptoms are related to stress

(50–

52). Several investigations have found that women medical students, residents, and physicians are more depressed than their male counterparts

(53–

58). Other work has reported that women physicians have a higher rate of depression than the general population

(13,

52,

59,

60). In 1987, a questionnaire study

(55) of 70 British women physicians found that 46% had scores indicative of depression, and 7% reported suicidal ideation. These physicians reported that their most significant stressors were role conflict and sexual harassment; those who were depressed perceived more stress

(55). Suicidal thoughts were reported by 13% of the medical students and 11% of the house staff in a study at a Midwestern medical school

(56). Olkinuora and colleagues

(61) surveyed a representative sample of practicing Finnish physicians. They found a more frequent occurrence of suicidal intent in that group than in the general population; 22.1% of the men physicians and 25.9% of the women physicians had a history of suicidal ideation or attempts. However, other investigations have found no difference in the incidence of psychiatric illness between men and women physicians

(62) and lower rates of depression in women family physicians than in the general female population

(63).

Unfortunately, there has been little work done on parasuicidal behavior. Most authorities agree that suicide attempts outnumber completions by a significant amount; women demonstrate nonfatal suicidal behavior two to three times more than men

(64,

65). Suicide attempts in women have been associated with the third decade of life, being working class, being housewives, with unemployment, less education, financial problems, being single (single, separated, or divorced); with domestic abuse, powerlessness, personality characteristics (dependence); or having family members with psychological difficulties. Given that some of these conditions (e.g., being working class, housewives, unemployed, or less educated) are less prevalent in women physicians, our a priori hypothesis for this investigation was that whereas the rate of suicide completion in women physicians may be higher than that of other women, the rate of suicide attempts in women physicians would not exceed that of other women.

To examine the prevalence and correlates of depression and suicide attempts in women physicians, we used the results of the Women Physicians’ Health Study, a large (N=4,501 respondents, 716 questions), nationally distributed questionnaire as our database. The Women Physicians’ Health Study contains information on multiple aspects of physicians’ self-identified histories and current practices. One component of the survey centered on psychological and social characteristics in order to examine the parameters of psychosocial functioning. Data on several factors related to suicide were collected, such as histories of suicide attempts, psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, and stress for each subject and her family members.

METHOD

The design of the Women Physicians’ Health Study has been more fully described elsewhere

(66), as have the basic characteristics of the population

(67,

68). The Women Physicians’ Health Study surveyed a stratified random sample of U.S. women M.D.’s; the sampling frame was the AMA’s Physician Masterfile, a database intended to capture all M.D.’s residing in the United States and its possessions. By using a sampling scheme stratified by decade of graduation from medical school, we randomly selected 2,500 women from each of the last four decades of graduating classes (1950 through 1989). We oversampled older women physicians, a population that would otherwise have been sparsely represented by proportional allocation because of the recent increase in the number of women physicians. We included active, part-time, professionally inactive, and retired physicians, age 30–70 years, who were not in residency training programs in September 1993 when the sampling frame was constructed. In that month, the first of four mailings was sent out; each mailing contained a cover letter and a self-administered, four-page questionnaire. Enrollment was closed in October 1994 with 4,501 respondents.

Of the potential respondents, 23% were ineligible to participate because their addresses were wrong, they were men, or they were deceased, living out of the country, or interns or residents. Our response rate was 59% of the physicians eligible to participate. We compared respondents and nonrespondents in three ways: we used a phone survey and compared the telephone responses of 200 nonrespondents with those of the respondents to the written survey, we compared all respondents with all nonrespondents with the AMA Physician Masterfile, and we examined respondents to survey mailing waves 1 to 4 to compare respondent and nonrespondent outcomes on a large number of key variables. From these three investigations, we found that nonrespondents were less likely than respondents to be board certified. However, respondents and nonrespondents did not consistently or substantively differ on other tested measures, including age, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, alcohol consumption, fat intake, exercise, smoking status, hours worked per week, frequency of being a primary care practitioner, personal income, or percentage actively practicing medicine.

On the basis of these findings, we weighted the data by decade of graduation (to adjust for our stratified sampling scheme) and by decade-specific response rate and board certification status (to adjust for our identified response bias). Using these weights allowed us to make inferences for the entire population of women physicians who graduated from medical school between 1950 and 1989. Because of our weighting strategy, all analyses on the Women Physicians’ Health Study data were run in SUDAAN, in which chi-square tests of independence are based on methods presented by Koch and colleagues

(69). By using the Bonferroni correction method to adjust for multiple testing, we set a conservative criterion of p≤0.001 as our significance level. Upper-tailed values of the chi-square distributions were used to locate rejection regions.

For this study, we examined the responses to the questions on depression and suicidal behavior (which were queried separately): “Please mark any known conditions in the columns below that you or your family [children, mother, father, siblings, and current spouse, queried separately] have now or have experienced in the past:…depression…attempted/completed suicide.” “Never” was not listed as a choice.

RESULTS

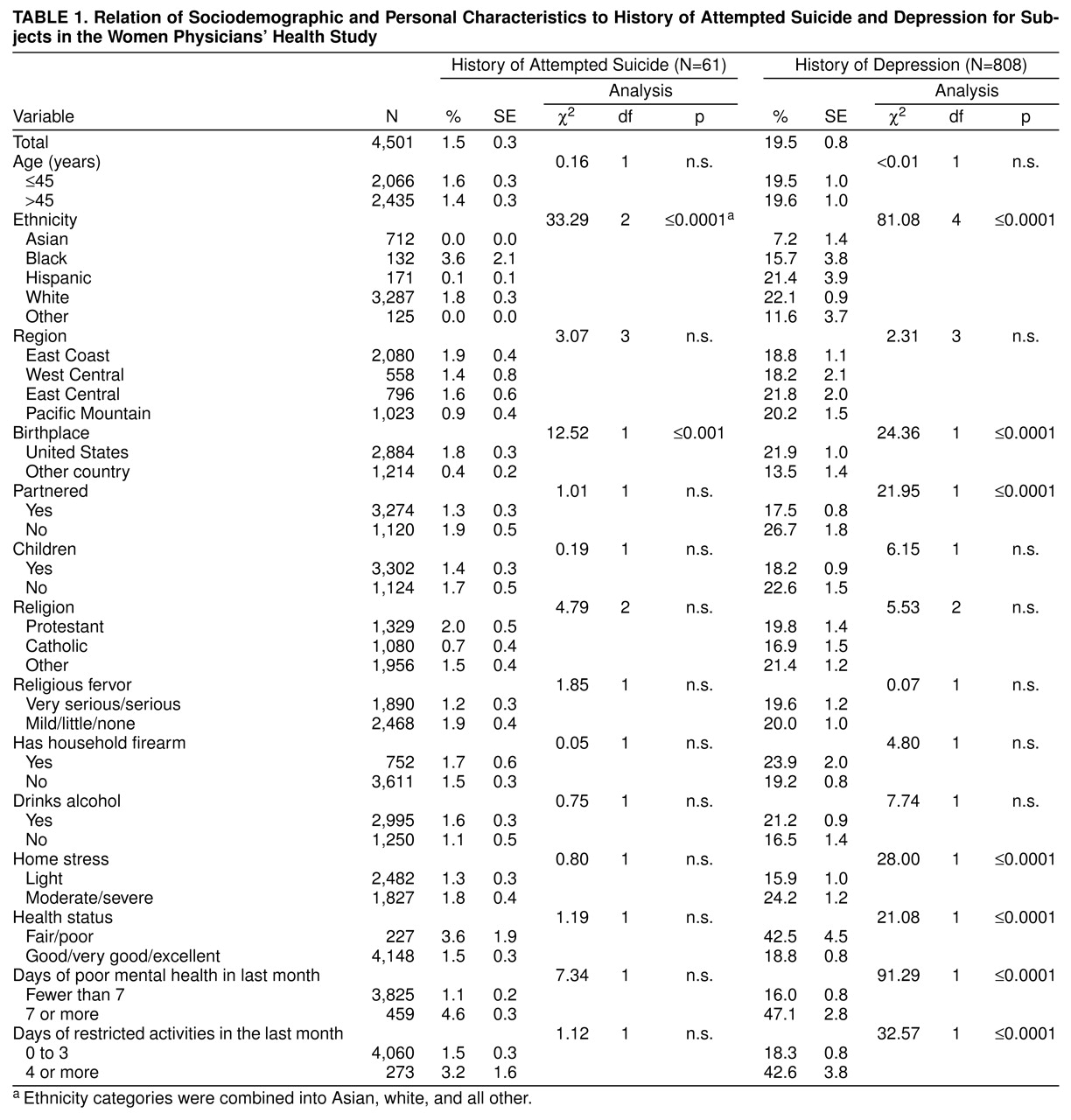

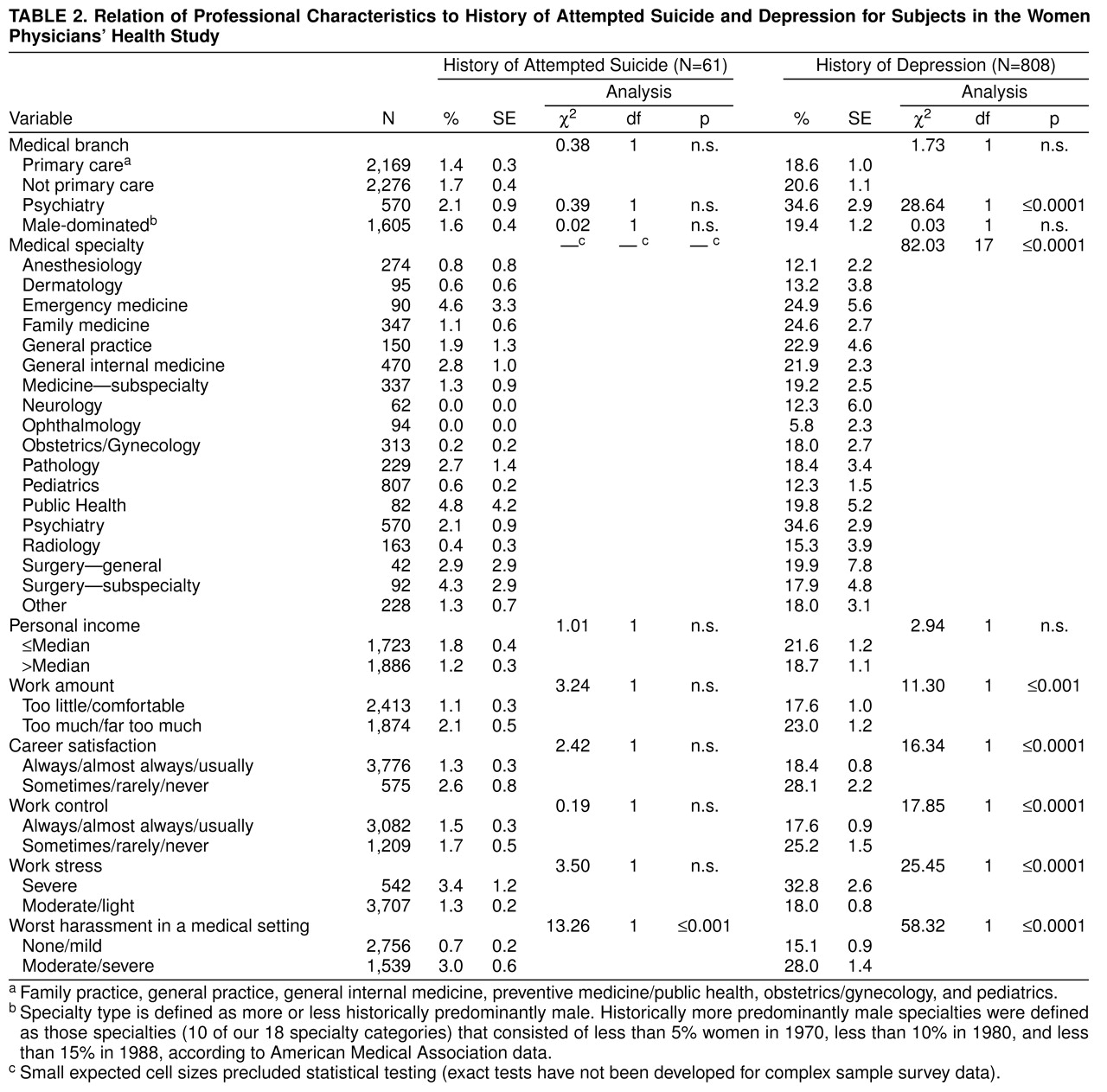

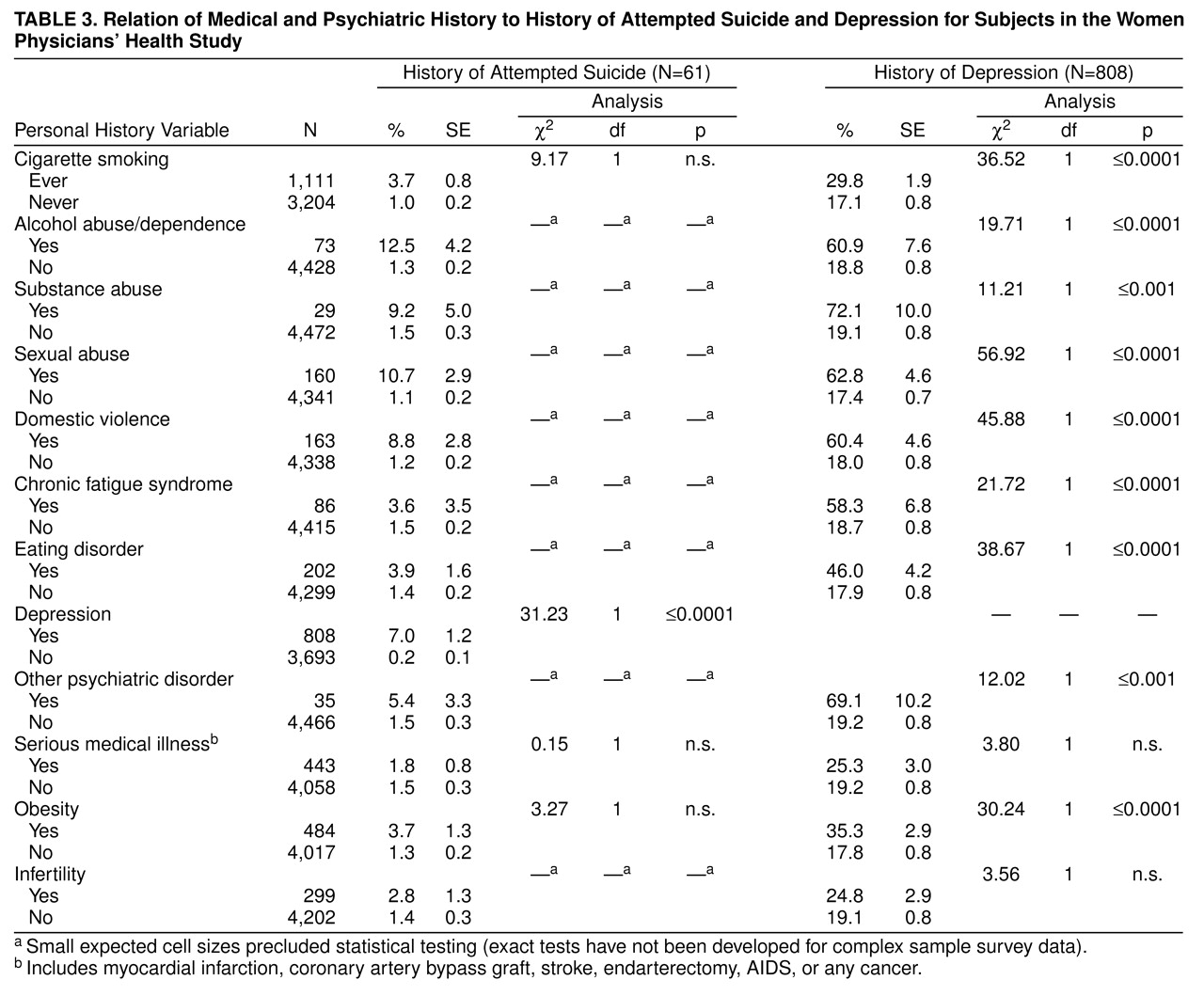

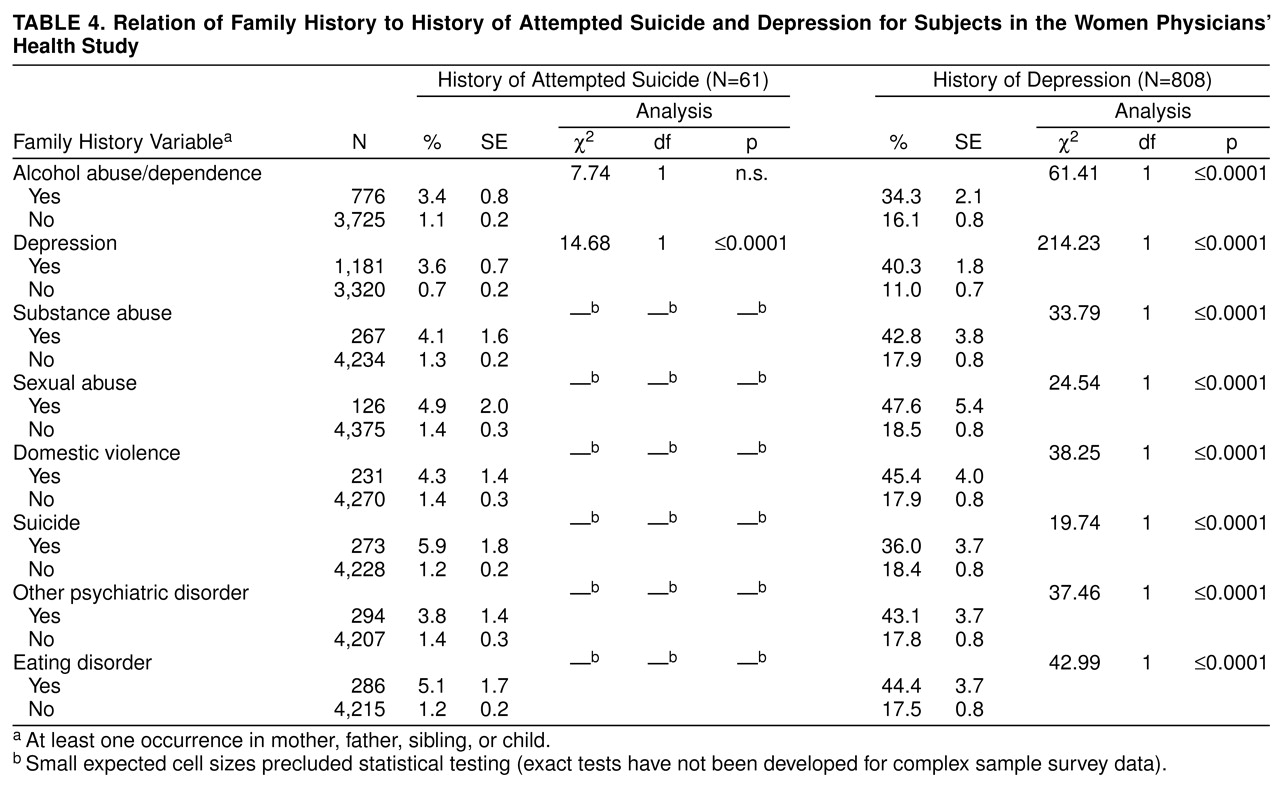

Overall, an estimated 1.5% (N=61) of women physicians reported having attempted suicide, and 19.5% (N=808) reported having a history of depression. Physicians’ self-reported depression rates for their family members (not shown) ranged from 2.4% (for physicians’ children) to 16.4% (for their mothers), and family members’ rates of attempted or completed suicide ranged from 0.4% (for their spouses) to 3.6% (for their siblings). Those who were not Asian, were born in the United States, had 7 or more poor mental health days in the past month (

table 1), had a history of severe harassment in a medical setting (

table 2), had a personal history of smoking cigarettes, alcohol abuse or dependence, sexual abuse, or domestic violence (

table 3); or had a family history of alcohol abuse/dependence, domestic violence, depression, suicide, or eating disorders (

table 4) were more likely to report their own attempted suicide or self-identified depression. Those who were not partnered, were childless, had a household firearm, drank alcohol, reported more home stress, poor health, or more days when poor physical or mental health restricted their activities in the past month were more likely to report self-identified depression (

table 1). Depression was also significantly more frequently reported by psychiatrists, those who felt they worked too much, who were dissatisfied with their careers, who reported less control over work, who reported more work stress (

table 2), those who had a history of substance abuse, chronic fatigue syndrome, an eating disorder, another psychiatric disorder, obesity (

table 3); and those who had a family history of substance abuse, sexual abuse, and other psychiatric disorders (

table 4). Attempted suicide is rare, and therefore cross-sectional data is a suboptimal method of examination. Many point estimates were unstable, yet despite this, it is noteworthy that a higher prevalence of attempted suicide was consistently associated with the characteristics also significantly associated with depression. Partially validating these associations is our finding that those who reported a history of depression were substantially more likely to have attempted suicide than those without a history of depression (7% and 0.2%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The lifetime risk of major depression for U.S. women has been estimated by various sources as between 7% and 25%

(70); our study found a similar rate of depression (19.5%). A few studies on women physicians and other women professionals have found that such women have higher rates of depression than do their male counterparts, which is similar to findings in the general population

(52–

58). Several investigations have found higher rates of depression in women physicians and other women professionals than in other women; significant risk factors are role conflict and harassment

(51,

54,

55).

In the general population, risk factors for major depression include being a woman, less educated, not partnered; having another psychiatric illness; being employed as a homemaker; having suicidal behavior (ideation or attempts), substance abuse, alcoholism, stress, conflicted and abusive relationships, life dissatisfaction, physical difficulties, decreased function, feelings of helplessness, and a familial psychiatric history, according to DSM-IV and the National Comorbidity Survey

(70). In our study, women physicians with histories of self-identified depression shared many of these attributes, such as not being partnered, having histories of eating disorders and other psychiatric disorders, having histories of medical problems (including chronic fatigue syndrome, smoking, and obesity), having a history of alcoholism, being dissatisfied with career and work, having been harassed, having experienced sexual and physical abuse, feeling stressed, or having a familial psychiatric history.

The rate of 1.5% for suicide attempts in this study is low compared to the rate of attempts reported generally among U.S. women. National Institute of Mental Health data revealed that 2.9% of the population reported a suicide attempt; women reported a rate of 4.2%

(71). It may be that physicians, including women physicians, have lower rates of suicidal intent or higher rates of completion than does the general population or both. Other authors have raised this possibility and speculate that physicians who decide to take their own lives may be more successful at it because they have better access to lethal methods and a better understanding of human anatomy and physiology

(18).

Factors that have been associated with physician suicides are single status, chronic mental and physical disorders, poor health, alcohol misuse, stress, career dissatisfaction, and psychiatry as a career

(1,

4,

10,

30), which were all (with the exception of psychiatry as a career) associated with suicide attempts in this survey. Conflicted and unsatisfactory relationships at home and at work have been identified as significant risk factors in physician suicides

(4); the greater occurrence of sexual abuse, domestic violence, and harassment in the individuals we studied may be markers for such conditions. We also found that depression was highly associated with suicide attempts. Others have found that physicians who attempt suicide (as with others who attempt suicide) tend to have histories of prior parasuicidal behavior

(4).

Family histories were associated with both suicide attempts and depression. Women physicians with histories of depression and suicide attempts in this survey were more likely to have family histories that were significant for depression, suicide and suicide attempts, substance abuse, other psychiatric disorders, domestic violence, and sexual abuse. Personal and familial psychiatric problems have previously been considered to be significant contributors to physician (and others’) suicides; affected physicians are more likely to have problematic families and childhoods. In a long-term project, Vaillant et al.

(72) concluded that physicians with problematic childhoods tended to have poor marriages, drug and alcohol abuse, or psychiatric problems. Other authors have identified disturbances in childhood, family histories of psychiatric disorders, and past psychiatric illnesses as predisposing physicians to addiction and psychiatric illness.

It is interesting that this study found associations between certain characteristics and self-identified depression or suicidal behavior or both in these women physicians that have not been commonly reported, including being non-Asian, being born in the United States, and having a firearm. These traits have not previously been systematically studied; prior research on suicide and suicidal intent in professionals (including physicians) has not considered race, ethnicity, or country of origin

(1). While there are somewhat more data on firearms and suicide, most such investigations have concentrated on the relationship between gun use and suicide completion (since a significant number of completed U.S. suicides involve firearms). Men are more likely than woman to employ firearms in committing suicide, but the number of women using guns to commit suicide is increasing

(64). Given these facts, it is of particular concern that women physicians with histories of depression are more likely than other women physicians to have household firearms.

The limitations of this study include the biases of self-reporting (e.g., skipping questions, nondisclosure, and different interpretations of meaning), the lack of standardized interviews or specific criteria for making psychiatric diagnoses, incomplete information (e.g., no items on mental health treatment and uncertainty regarding timing of reported conditions), not including suicide victims (suicide attempts are a somewhat different phenomenon than completed suicides), and the difficulty of comparing estimates of a rare event (i.e., attempted suicide). Comparing these results to those of other studies also may be problematic given the wide variability in sample sizes, populations, methodology, and research questions. However, this work provides some preliminary information on a large database of living women physicians, similar to some of the studies done in Europe, and provides a basis for further exploration. These results indicate that women physicians have a prevalence of depression similar to that of the general female population. However, although their suicide completion rate seems to be, per prior literature, somewhat higher than that of other U.S. women, their suicide attempt rate may be lower. Additional investigations are necessary to describe factors and influences related to suicide in women physicians so that appropriate interventions can be designed and implemented. In the interim, this study provides some new clues to potentially identifying, clarifying, and reducing psychiatric morbidity and mortality in U.S. women physicians.