One of the major goals of schizophrenia research in the past three decades has been the identification of precursor symptoms and areas of dysfunction before the manifestation of schizophrenia. Psychological and neurodevelopmental abnormalities in preschizophrenic persons have repeatedly been described, and it is now well established

(1–

3) that early signs of the disorder can be found during infancy. Presumably, these neuropsychological domains influence the individual’s interpersonal functioning and behavior. Consistent with this assumption are results from earlier investigations using retrospective designs (e.g., reference

4) or follow-back designs (e.g., references

5–

7) that have shown behavioral deviations in children who later developed schizophrenia, years before the onset of overt psychosis. Prospective studies

(8,

9) have confirmed associations between childhood developmental characteristics, including behavioral abnormalities, and adulthood onset of schizophrenia. But still, there is some question with respect to specificity, i.e., whether behavioral disturbances precede only schizophrenia or, rather, indicate general psychiatric difficulty in adulthood. Some investigators have found that schizophrenic individuals can be distinguished from patients with other mental disorders and nonpsychiatric groups by early behavioral abnormalities

(8), whereas others have failed to do so

(10,

11).

In a 20-year follow-up of school children by Champion et al.

(12), behavioral disturbance was shown to be related to a markedly higher rate of severely negative life events in adulthood. Such events, in turn, might put these subjects at greater risk for various psychiatric disorders in adult life. Children who display behavioral problems are also known to be at higher risk for developing externalizing disorders, such as alcohol and drug abuse

(13–

16). While rates of substance abuse are considerable in schizophrenia and affective disorder

(17,

18), the effect of this comorbidity with respect to early behavioral abnormalities is unclear.

The high-risk method was developed to assess early social, psychological, and biological characteristics in individuals with higher than average risk of mental disorders, before the onset of psychopathology, by using a prospective, longitudinal research design. The advantages of the high-risk design have been put forward many times (e.g., reference

19). Children at risk for schizophrenia by virtue of having at least one schizophrenic parent behave differently at school from other children in that they present greater disharmony, less scholastic motivation, and more emotional instability than comparison subjects

(20). In the New York High-Risk Project, which began in 1971, offspring of schizophrenic and affectively ill parents have been followed from childhood to midadulthood. The project thus provides a valuable opportunity to prospectively compare behavioral antecedents of a broad range of adulthood psychiatric disorders. The purpose of this analysis was to examine longitudinal associations between childhood behavioral problems reported by the parents at the initial assessment, when the children were on average 9.5 years old, and clinical outcomes after 25 years of follow up, with consideration of patterns of comorbidity with substance abuse.

RESULTS

Adulthood Clinical Outcome and Parental Diagnosis

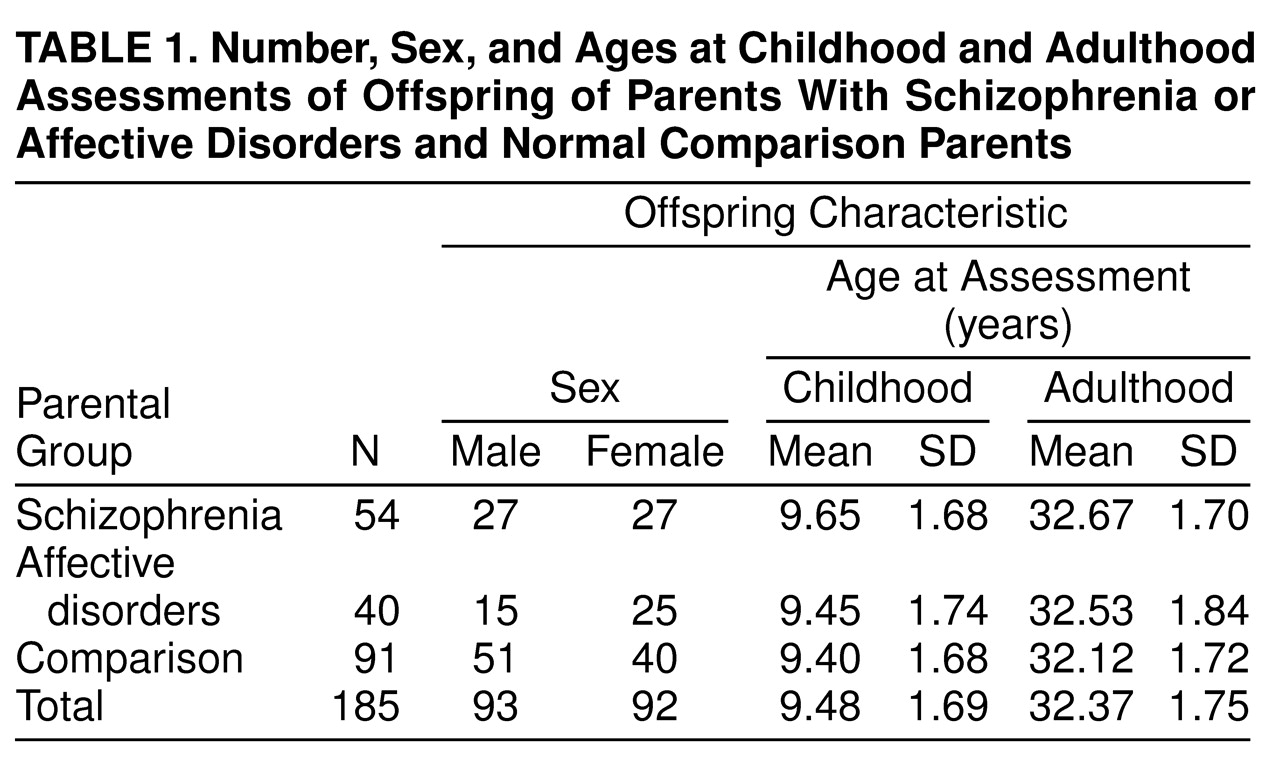

Schizophrenia occurred only in the offspring of schizophrenic parents, and the rate of schizophrenia-related psychoses as a whole differed significantly between that group (18.5%, 10 of 54) and the offspring of the normal comparison parents (1.1%, one of 91) (p<0.001). The broad category of schizophrenia-related psychoses did not differ significantly between the offspring of the schizophrenic and affective disorders groups because of the high rate of schizoaffective disorder in the offspring of the affectively disordered parents (10.0%, four of 40). However, it did significantly distinguish the offspring of the affectively disordered parents and the offspring of the normal comparison parents (p=0.03). The other clinical outcome categories did not differ in the three parental diagnostic categories.

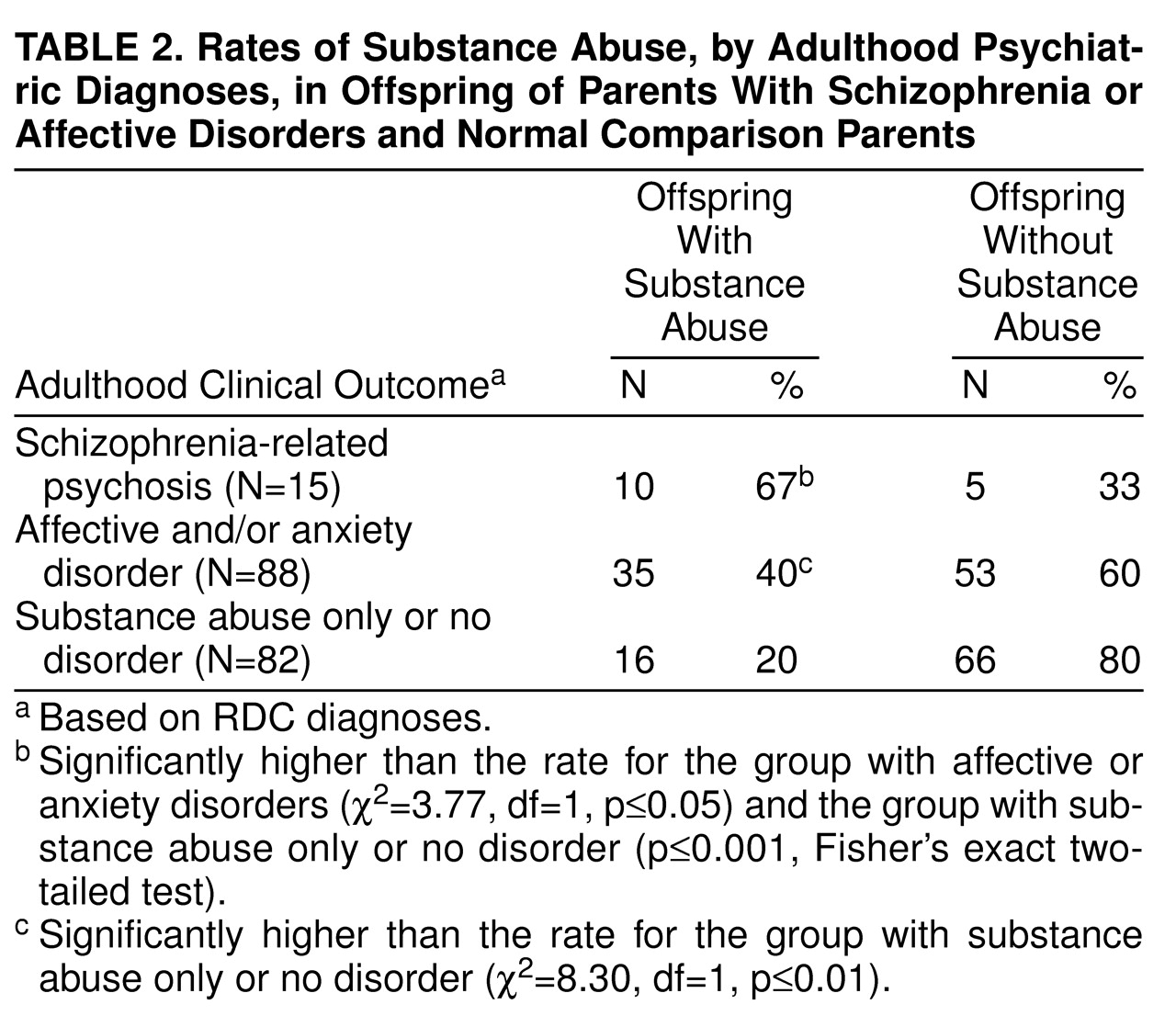

Adulthood Clinical Outcome and Substance Abuse

Table 2 shows the rates of substance abuse in each of the adulthood outcome categories (schizophrenia-related psychoses, affective and/or anxiety disorders, and substance abuse only or no disorder). The rates of substance abuse were significantly higher in both the group with schizophrenia-related psychoses and the group with affective and/or anxiety disorders than in the group with substance abuse only or no disorder. Additionally, the difference between the groups with schizophrenia-related psychoses and with affective and/or anxiety disorders was significant.

Childhood Behavior and Parental Diagnosis

We expected higher rates of childhood behavioral problems in the offspring of schizophrenic parents than in the offspring of parents with affective disorders or offspring of normal comparison subjects. The mean scores for childhood behavior were as follows: offspring of schizophrenic parents, 6.30 (SD=1.63); offspring of parents with affective disorders, 6.68 (SD=1.55); and offspring of normal comparison parents, 6.89 (SD=1.58). Lower scores reflect a greater number of behavioral problems reported by the parents. A one-way ANOVA for the parental diagnostic groups showed no group differences (F=2.38, df=2, 182, p=0.10).

Childhood Behavior and Adulthood Clinical Outcome

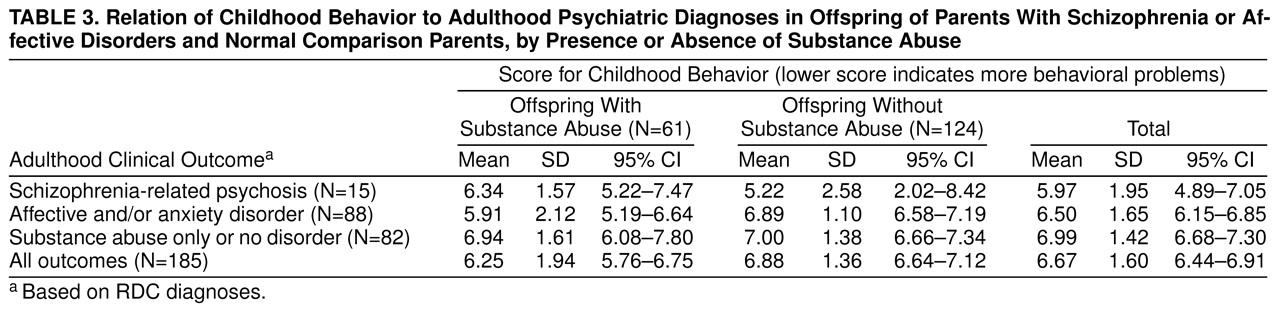

Table 3 shows childhood behavior scores in relation to adulthood clinical outcome, by presence or absence of substance abuse.

A three-way ANOVA using childhood behavior as the dependent variable and clinical outcome, substance abuse, and gender as the independent variables yielded a significant main effect for clinical outcome (F=4.97, df=2, 173, p=0.008), with schizophrenia-related psychosis having the lowest mean score for childhood behavior, and a significant interaction between clinical outcome and substance abuse (F=4.18, df=2, 173, p=0.02). Inspection of the mean scores for childhood behavior for the subjects with substance abuse showed no differences between the clinical outcome groups, while the mean scores for the subjects without substance abuse showed systematic differences. Therefore, we examined the differences in childhood behavior for the clinical outcome groups after excluding subjects with substance abuse from all diagnostic categories. We pooled across gender since it had neither a significant main effect nor an interaction with any of the other variables. After exclusion of the subjects with substance abuse, a one-way ANOVA with clinical outcome as the independent variable indicated that childhood behavior significantly differentiated the outcome groups (F=4.20, df=2, 121, p=0.02). Tukey honestly significant difference pairwise multiple comparison tests supported our hypothesis that subjects who developed adulthood schizophrenia-related psychoses displayed significantly more behavioral problems in childhood than those with adulthood affective and/or anxiety disorders (p=0.02) or those with substance abuse only or no disorder (p=0.01).

To address the question of the specificity of childhood problem behaviors that are associated with schizophrenia versus those associated with internalizing disorders, we performed chi-square analyses on the individual items composing the childhood behavior variable. We found no significant difference for any of the behavior items between the group with adulthood schizophrenia-related psychoses and the group with affective and/or anxiety disorders.

DISCUSSION

The New York High-Risk Project provided a rare opportunity to examine possible differences among the three parental risk groups with respect to childhood behavioral disturbances and, more important, the relationship between such disturbances and different psychiatric outcomes in adulthood. It is essential to note, however, that as core schizophrenia occurred only in the offspring of schizophrenic parents and the even broader category of schizophrenia-related psychoses was very rare (1.1%) in the normal comparison group (

22,

27)), no inferences can be drawn about a predictive relationship between childhood behavioral problems and later development of these diagnoses in the general population. This caution is not applicable to the other outcome categories, whose rates did not differ in the three parental risk groups.

Although the hypothesized differences between the parental risk groups with respect to childhood behavior problems were not found, several other significant relationships did emerge, especially when the influence of substance abuse was taken into account. While substance abuse showed a significant interaction with our outcome groups, it is notable that in the group with adulthood schizophrenia-related psychoses, childhood behavioral problems were greater among subjects without substance abuse (mean score=5.22) than those with comorbid substance abuse (mean score=6.34). (Lower scores reflect more behavioral problems.) Carpenter and colleagues

(29) have described a deficit form of schizophrenia, in which low rates of substance abuse and early manifestation of the disorder are typical. Our subjects with adulthood schizophrenia-related psychoses but no substance abuse, who exhibited the most marked behavioral abnormalities in childhood, might have such a deficit form of schizophrenia. To investigate group differences in schizophrenia-related psychoses, we looked at the ages at onset of psychosis in subjects with and without substance abuse. The mean ages at onset in the subjects with schizophrenia-related psychoses with substance abuse and schizophrenia-related psychoses without substance abuse were 21.30 years (SD=5.25) and 17.60 years (SD=3.65), respectively. However, to be less speculative, we would need to rate our subjects with schizophrenia-related psychoses for the deficit syndrome. In the other outcome groups (affective/anxiety disorders and substance abuse only or no disorder), as shown in

table 3, more behavioral problems in childhood were exhibited by subjects with substance abuse than by those without.

Our findings show considerable consistency with the results of prior investigations on behavioral problems as antecedents to schizophrenia (e.g., references

7,

30, and

31) and research pointing to childhood behavioral problems as precursors of the onset of substance use during adolescence

(17), substance use disorders generally

(15,

16,

32), and alcoholism specifically (e.g., references

33 and

34). The need for more investigation into the relationships among childhood behavioral problems, substance abuse, and other psychiatric outcomes is demonstrated by 1) our finding of significant interactions among these three dimensions and 2) the observation that subjects without substance abuse who later developed schizophrenia-related psychoses had significantly more childhood behavioral problems than those who developed affective and/or anxiety disorders or no mental disorder.

One possible limitation of the analyses could be the exclusive reliance on parents as a source of data on childhood behavior. While data from additional sources might have improved the validity of these assessments, the parental ratings reflect the subjective attitude of the parent toward the child and may be considered to provide information about the parent-child interaction and, thus, the family climate in which the child was brought up. The factor reflecting childhood behavior, based on parental ratings, has been used previously in the New York High-Risk Project in an examination of the relationship of life-history variables to various pathological outcomes

(26). That analysis revealed a negative relationship between a high score on the factor (reflecting good child behavior) and hospitalization for psychiatric disorders by a mean age of 27, indicating that subjects with a low frequency of childhood behavioral problems are unlikely to be hospitalized for mental disorder in young adulthood. The results presented here give further and stronger evidence of a remarkable degree of continuity over a long time period involving both a major change in environment and multiple life transitions. Teachers’ reports

(30) have also been shown to constitute an important and reliable source of information on childhood behavior. Although our data examined here came from the parents, an earlier New York High-Risk Project report noted that teachers’ ratings of problem behavior in school

(20) described young adolescent subjects at risk for schizophrenia as “unpleasant, unpopular, negativistic, maladjusted, nervous and low motivated” compared with normal comparison subjects. Thus, teachers’, as well as parents’, reports have indicated a higher frequency of behavioral problems in the offspring of schizophrenic parents than in the normal comparison children in this sample.

Another potential limitation of these analyses is that externalizing behavioral problems may be an overt expression of different underlying etiopathic entities linked to different developmental pathways and disorders and that the childhood behaviors considered here are rather crude and unspecific. However, these behaviors were not chosen arbitrarily but were derived from a factor analysis, and our results are consistent with well-established findings from child psychiatric studies

(35 showing that parents can more reliably detect externalizing behaviors than internalizing processes or more complex features, such as social competence. Also important to point out is that the childhood behavior variable does not relate to the concept of conduct disorder in childhood, which is characterized by antisocial and aggressive behavior

(36). Thirteen subjects (7%) from our sample here received the diagnosis of “conduct disorder in their past” during the first diagnostic follow-up in the New York High-Risk Project, when they were in their early 20s. Their mean score for childhood behavior (7.08) did not differ from the mean for the group with substance abuse only or no disorder. However, only one of those subjects developed schizophrenia-related psychosis with comorbid substance abuse, four were diagnosed with affective disorder and substance abuse, one was diagnosed with pure substance abuse, one was diagnosed with affective and anxiety disorders, and six did not develop any adulthood psychiatric disorder.

Nonwhites were not part of the original samples in the New York High-Risk Project, which were obtained at the beginning and middle of the 1970s. Our conclusions are thus limited to Caucasian (white) populations. Also, as noted earlier, the findings with respect to schizophrenia-related psychoses cannot be generalized beyond the offspring of schizophrenic parents.

In summary, our results support the view that in offspring of schizophrenic parents, schizophrenia-related psychoses can be followed back to early disturbances and suggest that childhood behavioral problems have links to adulthood psychopathology. At this point it remains to be explored whether the types of childhood behavioral disturbances considered here are related to other dysfunctions, such as attentional deviance and affective abnormalities, which have previously been reported to distinguish subjects at high risk for schizophrenia and preschizophrenic persons from normal comparison subjects. However, regardless of parental risk group, children characterized by early behavioral dysfunction also seem to be more likely to develop other psychiatric disorders in adulthood than subjects free of such childhood problems.