Subjects

Subjects were a nearly consecutive series of 322 adolescent inpatients admitted to the evaluation and crisis intervention unit of a private, nonprofit psychiatric teaching hospital. These patients were hospitalized for a variety of serious psychiatric problems. Patients were admitted on the basis of need for inpatient-level intervention; no other selection processes were used.

Inclusion criteria for the study population included 1) an adequate ability to read and comprehend the psychological evaluations used (see Procedure), 2) not actively psychotic, and 3) not so cognitively impaired or agitated as to preclude testing. At admission, all subjects and their parents (or legal guardians) provided written informed consent for evaluation.

Of the 322 subjects, 137 (42.5%) were male, and 185 (57.5%) were female. Ages ranged between 13 and 19 years (mean=15.8, SD=1.5). Two hundred sixty-one (81.1%) of the subjects were Caucasian, 33 (10.2%) were African American, 26 (8.1%) were Hispanic American, and two (0.6%) were of other ethnicity. Subjects were predominately from lower- to middle-class families with 75 (23.3%) of the 322 subjects receiving public entitlements. Global Assessment of Functioning Scale ratings averaged 53.9 (SD=11.2) at the time of admission and averaged 62.5 (SD=10.3) for the year before admission.

DSM-III-R diagnoses were assigned at the time of discharge (independently of the testing described here). The most frequently assigned diagnoses were, in descending order, major depression (41%, N=133), dysthymia (39%, N=124), drug use disorders (38%, N=123), conduct disorder (24%, N=76), alcohol use disorders (22%, N=71), oppositional defiant disorder (21%, N=68), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (15%, N=47). These clinical consensus diagnoses were generated on the basis of a review of each patient’s history and presenting data by a multidisciplinary treatment team of experienced clinicians with faculty supervision (D.C.F.); semistructured diagnostic interviews were not employed. Medical record data and family reports/corroborations represented routine components of the diagnostic evaluations. The clinical-consensus psychiatric diagnoses are provided solely for descriptive and contextual information.

Procedure

Subjects completed a battery of self-report instruments within 1 and 4 days of admission. All of the measures were administered and scored by computer. A brief description of the measures follows.

The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory

(20) is a 160-item, self-report inventory developed and normed with clinical samples

(20,

21) and used with adolescent inpatients

(21,

22). The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory is characterized by good psychometric properties and good theoretical-substantive, internal-structural, and external-criterion validation

(20,

21). The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory has been validated against several measures of psychological functioning

(20). Millon and colleagues

(20) reported adequate test-retest reliability (correlation coefficients ranged from 0.57 to 0.92 for individual scales) and adequate internal consistency (alpha coefficients ranged from 0.73 to 0.91 for individual scales).

The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory contains basic validity checks (e.g., completeness, certain validity items—chosen because of their extremely low rates—that if endorsed might suggest insufficient attention to the test or carelessness). All subjects considered in this report passed the validity checks. The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory scoring process takes into account age, gender, and actuarial base rate data to establish scale scores. Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory scale score cutoffs are produced so that the frequencies of the scale scores correspond to actual trait frequencies in adolescent clinical populations (see

20,

21). The Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory also weights and adjusts scores based on test-taking attitudes (i.e., levels of disclosure, desirability, and debasement).

Two specific scales of the Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory were used for this study: the childhood abuse scale and the borderline tendency scale.

The child abuse scale contains 24 items that assess various forms of abuse (e.g., “People did things to me sexually when I was too young to understand”). High scores on this scale reflect adolescent self-reports of shame or disgust about having experienced sexual, physical, or verbal abuse from others. The childhood abuse scale showed adequate internal consistency in two validation samples (0.83 and 0.81) and a test-retest (3–7 days) correlation of 0.81 (20). Scores on the childhood abuse scale were significantly correlated with clinician judgments (r=0.43, p<0.001) in the original concurrent validation study

(20).

The borderline tendency scale contains 21 items that assess core emotional, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis. The borderline tendency scale showed adequate internal consistency in two validation samples (0.86 and 0.86) and a test-retest (3–7 days) correlation of 0.92

(20).

The Beck Depression Inventory, 21-item version

(23,

24), is a well-established and widely used inventory of the cognitive, affective, motivational, and somatic symptoms of depression. It has been researched extensively with adolescents

(25), given its fifth-grade readability level

(26), and has been shown to have excellent psychometric properties with adolescent patients

(25,

27). Strober et al.

(27) reported an internal consistency of 0.79, a 0.67 correlation with clinical ratings of depression, and a 5-day, test-retest reliability of 0.69 for a sample of adolescent inpatients.

The Depressive Experiences Questionnaire for Adolescents

(28) is a 66-item, self-report questionnaire that assesses experiences noted in the lives of depressed patients but not necessarily regarded as clinical symptoms of depression. Responses are given on a 7-point, Likert-type scale. We focused on the two main factors of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire for Adolescents

(28,

29): interpersonal (dependent) dysphoria and self-critical dysphoria. The first factor, dependency, reflects a depreciated sense of self, dependency, and helplessness. The second factor, self-criticism, reflects self-blame, guilt, and a loss of autonomy. These Depressive Experiences Questionnaire for Adolescents factors have been replicated with community samples of high school students

(28–

30) and have demonstrated a high level of internal consistency, good retest reliability, and convergent validity

(28,

29).

The Hopelessness Scale for Children

(31) is a 17-item, true/false scale for children and adolescents that taps into negative future expectations. The Hopelessness Scale for Children has been used with adolescents and has demonstrated good psychometric properties

(32,

33). Internal consistency for the Hopelessness Scale for Children (0.97 alpha) is excellent, and test-retest reliability (0.52) is adequate

(31).

The Suicide Risk Scale

(34) is a 15-item, true/false self-report measure of feelings of hopelessness, present suicidal feelings, past suicidal behavior, and other items that have been shown to be associated with suicide risk. The Suicide Risk Scale has good internal reliability, with a coefficient alpha of 0.74 with adolescents, as well as good sensitivity and specificity

(34–

36). The Suicide Risk Scale has been cross validated with other inpatient samples and discriminates well between groups of patients who have and have not made suicide attempts

(35).

The Past Feelings and Acts of Violence Scale

(37) is a 12-item, self-report scale in which responses are coded on a 3-point continuum of frequency. The scale inquires about the frequency of feelings of anger, past acts of violence toward others, use of weapons, and history of arrests. The scale has been demonstrated to have good discriminative validity with adult psychiatric inpatients and with adolescents has been shown to have good internal consistency, item sensitivity, and specificity

(38).

The Impulsivity Control Scale

(35) is a 15-item, self-report scale designed to assess impulsivity that is independent of aggressive behavior; items are answered on a 3-point frequency scale. With adolescents, the Impulsivity Control Scale has good internal reliability and correlates well with other measures of suicide and violence risk

(35,

38).

The Drug Abuse Screening Test—Adolescents

(39) is a 27-item, self-report screening measure for substance abuse relevant for adolescent populations that has been adapted from the adult version

(40). The Drug Abuse Screening Test—Adolescents has demonstrated good psychometric properties in adolescent inpatient samples. Martino and colleagues

(39) reported good internal consistency (0.91 coefficient alpha), 1-week test-retest reliability of 0.89, and a positive predictive power for substance use disorders of 79%.

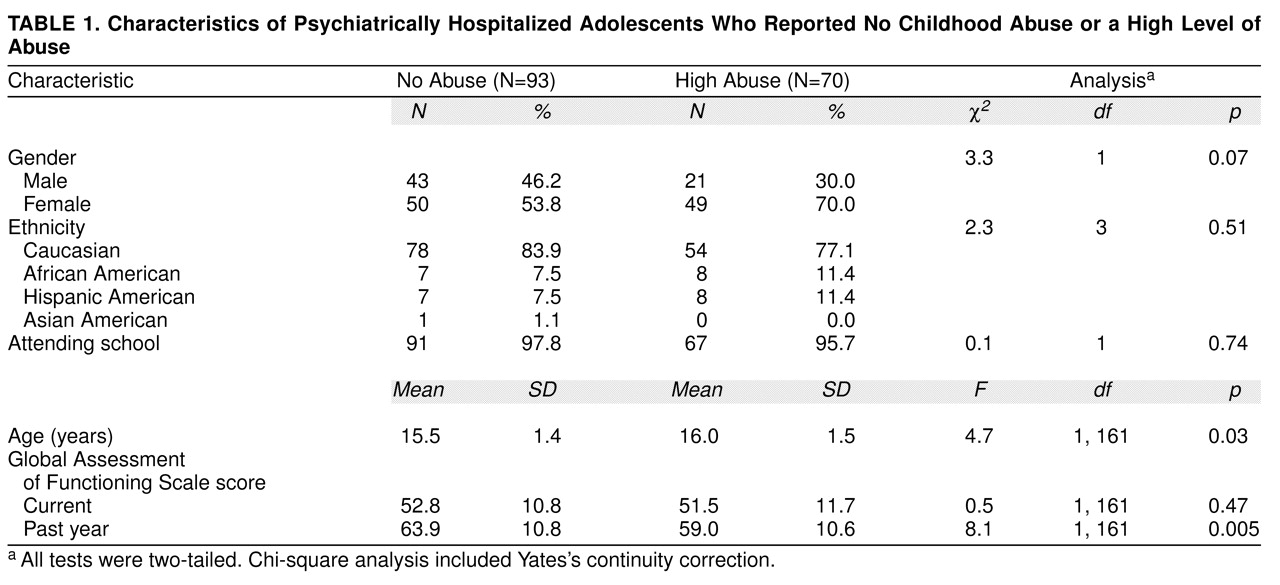

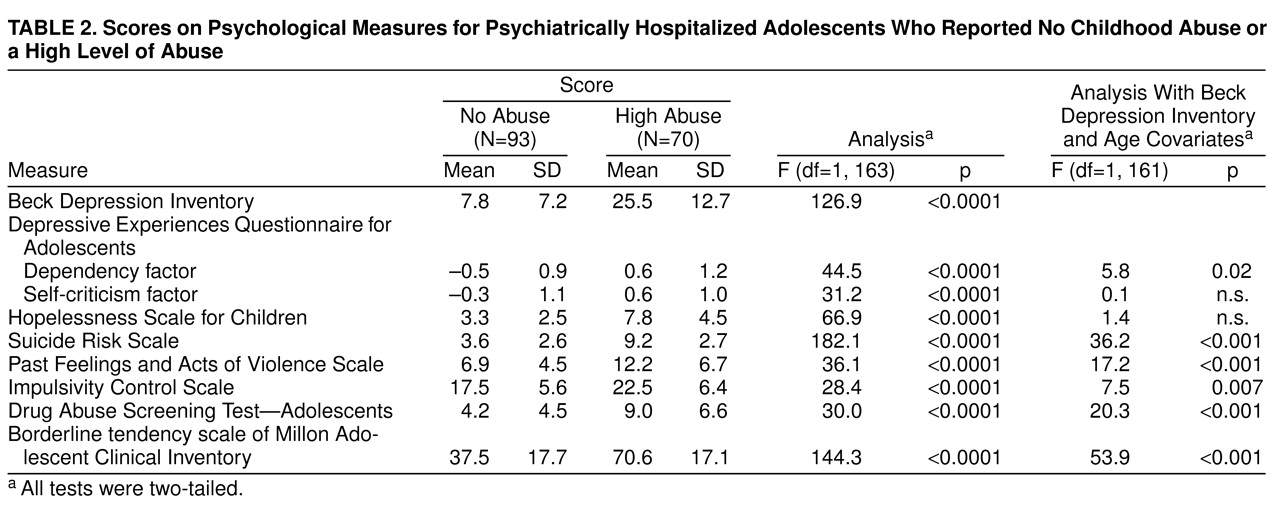

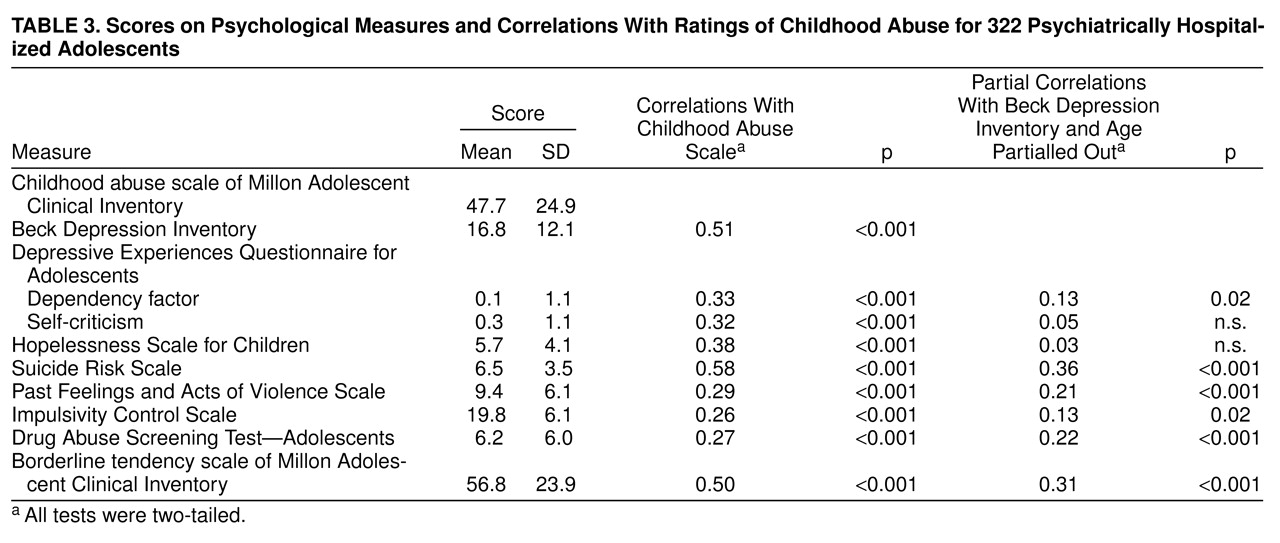

One hundred and sixty-three subjects comprised the two specific study groups selected for the categorical portion of this study. The 163 subjects were selected from the larger series of 322 admissions on the basis of their scores on the childhood abuse scale of the Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory. Childhood abuse scale scores of 30 or less and 70 or greater were used to create two study groups: no abuse (N=93) and high abuse (N=70), respectively.

Childhood abuse scale scores of 30 or less did not include endorsements of items directly assessing sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, whereas scores of 70 or greater (reflecting clinically significant elevations) did include endorsements of several items directly tapping abusive experiences. For our overall study group (N=322), a childhood abuse scale score of 30 corresponded to the 30th percentile, and a score of 70 corresponded to the 79th percentile.

To estimate concurrent validity, we tested the childhood abuse scores against information about abuse recorded in the clinical medical record. The records of 45 subjects (28% of cases) were randomly selected for a blind and independent review by a trained post-master’s-degree-level research associate. Subjects were rated by the reviewer as “no abuse” if no report was contained in the medical record, whereas a rating of “high abuse” required documentation of sexual, physical, and/or emotional abuse. Thirty-six (80%) of the 45 medical records were in agreement with the classification of subjects into either the “no abuse” or “high abuse” study groups (χ2=13.75, df=1, p=0.0002, two-tailed test with Yates’s continuity correction; kappa=0.57, p=0.00005).