Substance use disorders often occur in relation to other mental disorders, especially mood and anxiety disorders and antisocial personality disorder

(1–

4). The association of a variety of specific substance use disorders with antisocial personality disorder has been observed in clinical and forensic settings

(5,

6) and in the general population

(7,

8). In fact, in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study

(7), alcohol use disorders and all other DSM-III nonalcohol substance use disorders were more strongly associated with antisocial personality disorder than with any of the other axis I disorders examined in the survey.

Until recently, an exclusive focus on antisocial personality disorder in studies of the comorbidity of substance use and personality disorder has been influenced by both theoretical and practical considerations. Links between childhood aggression and impulsivity (i.e., conduct disorder) and the subsequent development of substance use disorders have been found

(9,

10). In turn, substance use disorders themselves often lead to other antisocial behavior

(11). And although overlap is apparent in the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder

(12), studies that have adjusted for symptom overlap have also found substantial comorbidity.

From a practical point of view, before the development of standardized, semistructured interviews for all axis II disorders, instruments were available only for antisocial personality disorder. Thus, a perception was created that substance use disorder/personality disorder comorbidity was limited to antisocial personality disorder. However, since impulsive tendencies may underlie other personality disorders in addition to antisocial personality disorder, it is reasonable to expect that a broader perspective on diagnosis of personality disorder might uncover a more extensive pattern of comorbidity

(13,

14).

To date, only 12 studies have been published in which a standardized, semistructured interview was used to assess all axis II disorders in the examination of substance use disorder/personality disorder comorbidity. Eleven of these

(15–

25) were conducted on clinical study groups, and one

(26) on a nonclinical group. All 12 studies found that substantial proportions of patients with substance use disorders also had personality disorders; not only antisocial personality disorder but also borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders were found. Except for the Zimmerman and Coryell study

(26), however, the comorbidity rates obtained in these studies are difficult to interpret, because no meaningful comparison groups of subjects without substance use disorders were included. Furthermore, all of the clinical studies used groups of drug-abusing patients who had presented to specialized drug or alcohol treatment inpatient units (N=6)

(15,

17,

18,

21–

23) or clinics (N=5)

(16,

19,

20,

24,

25). Thus, axis II disorders were not assessed blind to the presence of substance use disorders, and in all 12 studies, axis I and axis II evaluations were conducted by the same clinician.

The purpose of this study was to examine the extent of comorbidity of substance use disorders and personality disorders by comparing rates of personality disorders among patients with and without substance use disorders, diagnosed both currently and on a lifetime basis. The patients were seeking treatment primarily for problems related to personality psychopathology rather than for problems with substances. The patients were rigorously assessed by semistructured interviews for both substance use and axis II disorders, and personality disorder diagnoses were made blind to the assessments of substance use disorders. We examined whether patterns of personality disorder comorbidity were similar for alcohol and nonalcohol substance use disorders. We also evaluated the impact of comorbid personality disorder on chronicity and overall impairment associated with substance use disorders.

METHOD

One hundred subjects were recruited from applicants to each of two treatment settings in the New York State Psychiatric Institute: the General Clinical Research Service, a long-term, inpatient unit specializing in personality disorders, and the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research, an outpatient clinic providing low-cost psychoanalysis. Written informed consent was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained.

Fifty-two of the 100 inpatient applicants were hospitalized on the unit; an additional six were not, but were inpatients at other hospitals at the time of the evaluations. The remaining 42 applicants were outpatients who were not hospitalized. Fifty-eight psychoanalytic clinic applicants were accepted for analysis, and the remaining 42 were referred for other outpatient treatment. Details of the study group’s demographic characteristics are described elsewhere

(27). Fifty-six percent of the study group were women, 60.5% were under 30 years of age, 86.5% were white, 63% were college graduates, 81% had never been married, and 80.5% had been employed in the past year.

All 200 patients were independently interviewed face-to-face by two experienced clinicians. One clinician administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P)

(28), which includes questions to assess dependence or abuse associated with seven specific classes of substances (plus other substance abuse and polysubstance abuse), and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II)

(29) for axis II disorders. The other clinician used the Personality Disorder Examination

(30). The order of the interviews was alternated. The Personality Disorder Examination interviewer was blind to the results of the SCID-P and SCID-II; the SCID-II interviewer also administered the SCID-P but was blind to the results of the Personality Disorder Examination. The interviews were given by two of us (A.E.S. and J.M.O.), 11 other psychiatrists, and one senior social worker, whom we trained. Training consisted of reviewing interviews and manuals, observing two or three interviews conducted by an experienced interviewer, practicing the interviews independently, and having two or three interviews observed by the instructor.

Age at the onset of substance use disorders and the amount of time during the 5 years before the assessment that a patient experienced symptoms of each diagnosed substance use disorder were determined. The latter ratings were made on a 6-point scale: 1=not at all, 2=rarely (5%–10% of the time), 3=a substantial minority of the time (20%–30%), 4=about half the time, 5=a substantial majority of the time (70%–80%), 6=almost all the time (90%–100%). An assessment of global functioning was made on the DSM-III-R axis V Global Assessment of Functioning Scale.

In the statistical analyses, rates of one or more personality disorders among patients with and without DSM-III-R psychoactive substance abuse or dependence were calculated by using a conservative estimate of the presence of personality disorders in the comorbidity analyses. For the presence of personality disorders, we used diagnoses on which the results of the SCID-II and the Personality Disorder Examination converged; diagnoses on which the interviews were discordant were considered to be absent.

Comorbidity of substance use disorders and axis II diagnoses was examined by calculating univariate odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We examined the comorbidity of current alcohol, cannabis, and other substance use disorders and of lifetime alcohol, cannabis, stimulant, and other substance use disorders with each individual personality disorder, the three clusters specified in DSM-III-R, and any personality disorder. The significance of the odds ratios was determined by means of chi-square tests; the experimentwise error rate was set at 0.05 with the Bonferroni correction. We conducted logistic regression analyses to examine the multivariate relationship between substance use disorders and the 11 personality disorders.

Mean age at the onset of substance use disorders, mean rating of percentage of the last 5 years during which symptoms were present, and mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores of patient subgroups were compared by means of t tests.

RESULTS

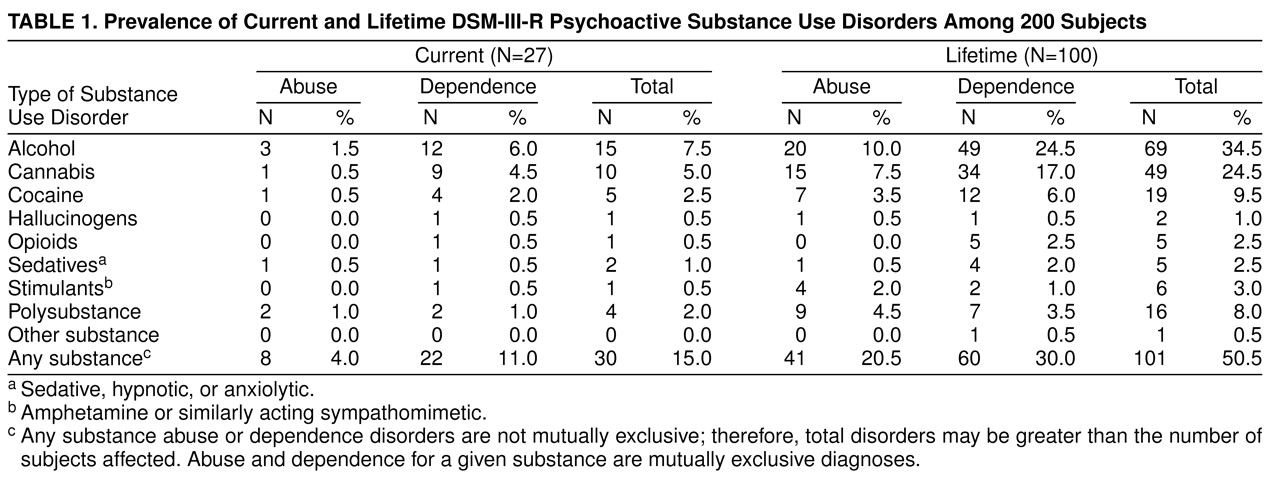

Table 1 shows the rates of current and lifetime psychoactive substance use disorders in the study group. Lifetime substance use disorders were much more common than current substance use disorders. A striking 50.5% of the total group had a lifetime disorder. Alcohol use and cannabis use disorders were the most frequent current and lifetime substance use disorders, with lifetime rates of 34.5% and 24.5%, respectively. Cocaine and polysubstance use disorders were relatively common on a lifetime basis (9.5% and 8.0%, respectively). Substances associated with abuse or dependence were not mutually exclusive; some patients had more than one substance use disorder.

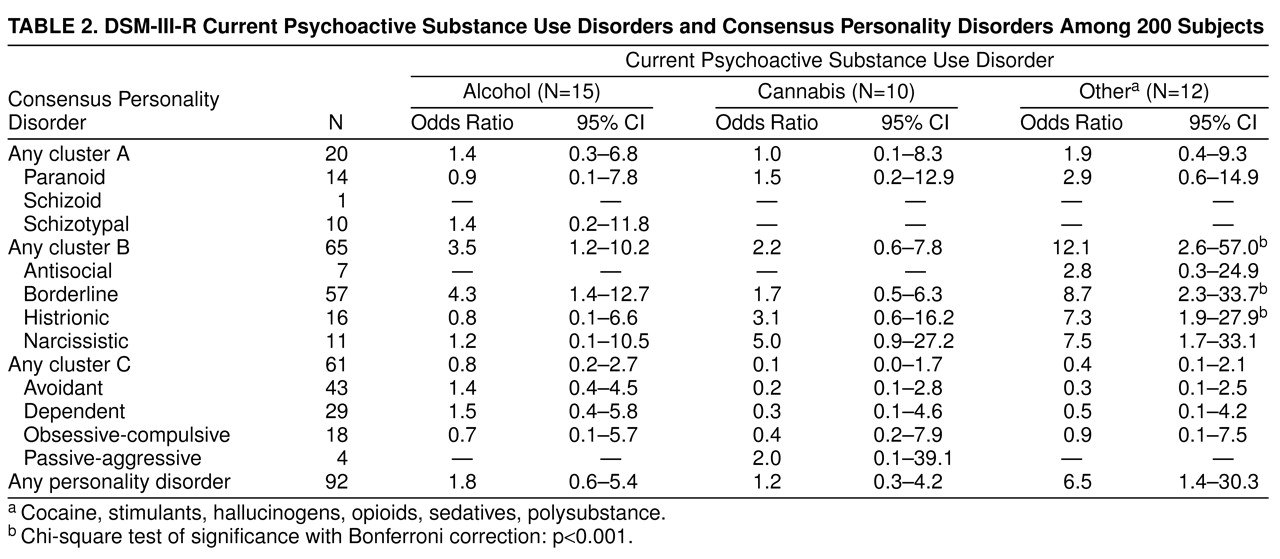

The frequencies of individual personality disorders can be seen in

table 2. Forty-six percent (N=92) of the study group had at least one consensus personality disorder. The most common personality disorders were from cluster B (borderline, 28.5%, N=57) and cluster C (avoidant, 21.5%, N=43; and dependent, 14.5%, N=29). Antisocial personality disorder (3.5%, N=7) was comparatively rare in this group of subjects.

Of the 27 subjects with a current psychoactive substance use disorder, 59% (N=16) were found to have a comorbid personality disorder. Only slightly more patients with a nonalcohol substance use disorder had a personality disorder (65%, N=11) than did those with either alcohol abuse or dependence (60%, N=9). Very similar results were found when substance use disorders were diagnosed on a lifetime basis. Fifty-five of the 100 subjects who had ever had a substance use disorder had a personality disorder: 63% (N=42) of those with lifetime nonalcohol substance use disorders and 55% (N=38) of those with lifetime alcohol use disorders.

In examining the univariate odds ratios for the association between current psychoactive substance use disorders and individual personality disorders in

table 2, it is apparent that the significant associations were limited to other substance use disorders, excluding alcohol and cannabis, which were more than seven times as likely to occur in subjects with borderline personality disorder (χ

2=13.55, df=1, p<0.001), and histrionic personality disorder (χ

2=11.13, df=1, p<0.001) as in subjects without these disorders.

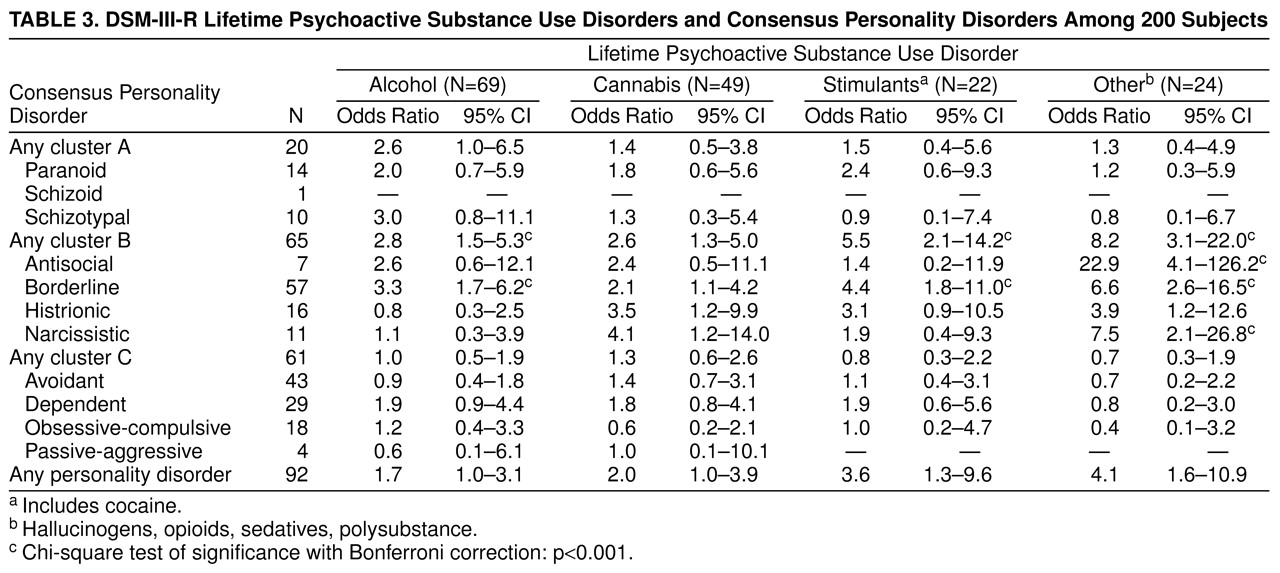

Turning to the univariate odds ratios for lifetime disorders (

table 3), we found significant associations with borderline personality disorder for alcohol use disorders (χ

2=13.95, df=1, p<0.001), stimulant use disorders (χ

2=11.35, df=1, p<0.001), and other psychoactive substance use disorders (χ

2=19.50, df=1, p<0.001). With stimulants separated out, other substance use disorders were also significantly associated with narcissistic personality disorder (χ

2=12.34, df=1, p<0.001). There was a very powerful association (odds ratio=22.9) between other lifetime psychoactive substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder (χ

2=24.26, df=1, p<0.001) that was not apparent for current substance use disorders.

Subjects in our study frequently had more than one personality disorder, and substance use disorders were associated with more than one personality disorder in our univariate analyses. To complement our univariate findings, we conducted a series of logistic regression analyses in which all 11 personality disorders were entered simultaneously into models predicting the current and lifetime substance use disorder groups of

table 2 and

table 3, respectively. These analyses were performed to determine whether the comorbidities we found in our univariate analyses were still present when all other personality disorders were controlled.

The overall model for personality disorder predicting current other substance use disorders was significant (model χ2=25.66, df=11, p=0.007). With other personality disorders controlled, the association with borderline personality disorder remained significant (odds ratio=11.1, Wald test value=9.68, df=1, p<0.01), but histrionic personality disorder did not add to the significance of the model. For lifetime alcohol use disorder, the overall model was significant (model χ2=23.67, df=11, p=0.01), and the association between borderline personality disorder and lifetime alcohol use disorders remained significant (odds ratio=4.5, Wald test value=12.66, df=1, p<0.001). The model for lifetime stimulant use disorders was not significant. The association between borderline personality disorder and stimulant use disorders remained significant (odds ratio=4.6, Wald test value=7.73, df=1, p<0.01). Finally, an overall model for personality disorders predicting lifetime other substance use disorders was significant (model χ2=40.67, df=11, p<0.0001). In this model both borderline personality disorder (odds ratio=11.5, Wald test value=17.63, df=1, p<0.001) and antisocial personality disorder (odds ratio=21.7, Wald test value=8.44, df=1, p<0.01) continued to predict lifetime other substance use disorders when co-occurring personality disorders were controlled, but narcissistic personality disorder did not.

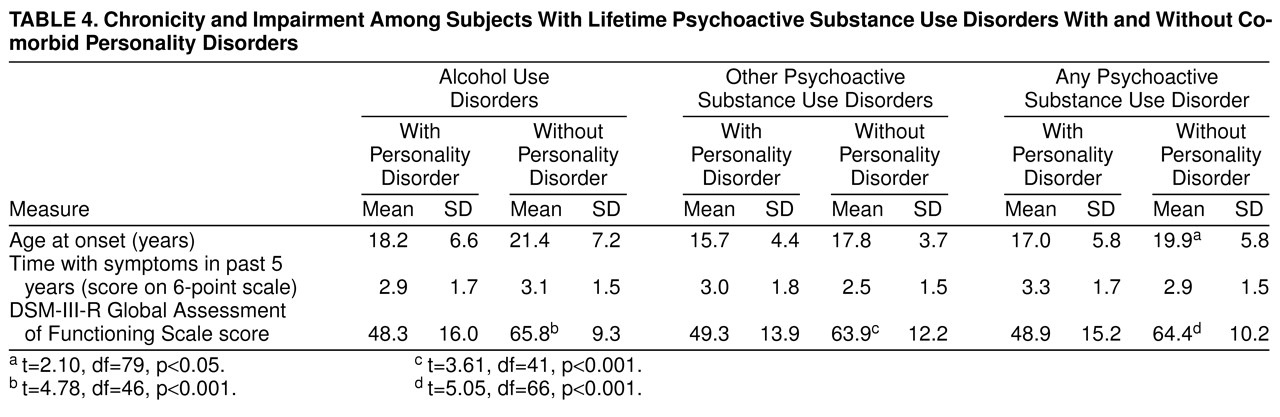

Table 4 shows the relationship of personality disorders to measures of chronicity and impairment in subjects with substance use disorders. Subjects with personality disorders tended to have an earlier age at onset of their substance use disorders, but this difference reached significance only for the combined group with any psychoactive substance use disorder. There were no differences in the amount of time in the past 5 years in which there were symptoms of a substance use disorder between the patients who had a comorbid personality disorder and those who did not. All groups had symptoms about 20%–30% of the time (corresponding to a score of 3 on the SCID scale). Global functioning, however, was much worse for patients with alcohol use disorder, other substance use disorders, or any substance use disorder if they had a comorbid personality disorder.

DISCUSSION

Our results concur with those of previous studies that used semistructured interviews to assess all axis II disorders in some respects. Our overall personality disorder rates of 59% of the subjects with current psychoactive substance use disorders and 55% of those with lifetime substance use disorders are remarkably consistent with the overall rate of 60% in the 1,483 substance-abusing patients and nonpatients in the 12 previously published studies

(15–

26). Eliminating the nonpatient sample of Zimmerman and Coryell

(26) raises the rate to 62% in the 1,278 patients in the remaining studies. Our rates of 65% for personality disorder in patients with current nonalcohol substance use disorders and 60% for those with current alcohol use disorders are similar to the results of the other 12 studies: an average rate of 61% was found in 12 nonalcohol substance abuse samples

(15–

19,

21–

26) and 59% in four alcohol abuse samples

(18,

20,

21,

26).

These overall rates of personality disorder in substance-abusing persons are interesting for three reasons. First, most earlier reports suggested that treatment-seeking patients had more severe and complex symptom patterns (i.e., what we now call comorbidity) than nonpatient persons in the community who had mental disorders, and thus they might be expected to have higher rates of personality disorder. In fact, the rate of 46% in the Zimmerman and Coryell

(26) nonpatient sample is significantly lower than the overall 62% rate found in the patients in our study and the others (χ

2=19.78, df=1, p<0.001). A second point of interest is the relative equivalence of comorbid personality disorders in patients with alcohol and nonalcohol substance use disorders. Commonly, comorbidity in patients with nonalcohol substance use disorders has been assumed to be greater than in patients with alcohol use disorders. Finally, our rates of personality disorder for current versus lifetime diagnoses are very similar. This suggests that the assessment of axis II disorders in the presence of a current substance use disorder may not be as difficult as previously assumed.

In addition to finding a high rate of personality disorder among alcohol and nonalcohol substance-abusing subjects, we have demonstrated that for current substance use disorders, the rate is elevated only for patients with nonalcohol and noncannabis substance use disorders. For this group of substance abusers, the odds of having a cluster B personality disorder were more than 12 times the odds for all other patients. This association was largely accounted for by borderline and histrionic personality disorders. All other patient samples of nonalcohol substance abusers in the 12 previously mentioned studies revealed an association with borderline personality disorder (one with cluster B disorders); all but one found an association with antisocial personality disorder as well. In addition, Zimmerman and Coryell

(26), Nace et al.

(17), DeJong et al.

(18), and Weiss et al.

(22) found high frequencies of histrionic personality disorder. This association may have resulted from the overlap of histrionic personality disorder with borderline personality disorder, as we discovered by means of our regression analyses.

We also found significantly elevated odds of borderline personality disorder in our patients with lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence. None of the other four studies of alcohol abusers found high rates of borderline personality disorder, but Thevos et al.

(21) found a high rate of cluster B disorders in general. On the other hand, Dulit et al.

(31) studied substance use by patients with borderline personality disorder and found that the substances most frequently used were alcohol and sedative/hypnotics. They also found, however, that when substance abuse was not used as a criterion for borderline personality disorder, a substantial number of these patients no longer met the criteria for borderline personality disorder. In our study group, a robust relationship between substance use disorder and borderline personality disorder remained, even when substance abuse was removed from the borderline personality disorder diagnostic criteria.

In our study, there was an earlier age at onset of substance use disorders when a comorbid personality disorder was diagnosed. This could indicate either that persons who eventually go on to have personality disorders have problems in adolescence that lead them to the earlier use and abuse of psychoactive substances, or that earlier pathological use of psychoactive substances leads to other problems in psychological and social functioning that come to be diagnosed as personality disorders. In a community sample of young children, Bernstein et al.

(32) found that conduct problems in children younger than 10 years of age were predictive of the development of personality disorders from all three DSM-III-R personality disorder clusters 10 years later. The continuity between childhood conduct problems and adolescent substance abuse has been well documented

(9,

10).

In contrast to their effects on eating disorders

(33) and anxiety disorders

(34), there was no evidence that personality disorders increased the chronicity of substance use disorders in this study group over the 5 years before assessment. We found a much higher rate of lifetime substance use disorders that were not current (73%) than of eating disorders (50%) or of anxiety disorders (22%). Therefore, in this relatively high-functioning group, substance use disorders were more episodic and less subject to the adverse effects on clinical course often associated with comorbid personality disorder

(35,

36). Consistent with our previously reported results on the comorbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders

(33,

34), personality disorders did result in significantly lower levels of global functioning in patients with substance use disorders, as would be expected

(24).

For at least three reasons, the findings in this study may not generalize to the overall population of persons seeking treatment for substance abuse. First, our patients were seeking treatment primarily for problems other than those related to substance use. Second, the proportion of women in our study group (56%) was considerably higher than in most study groups of patients with substance use disorders (29% in the axis II studies cited earlier)

(15–

26). Third, although our treatment settings are part of a state mental health system, they are not typical of public settings in which patients with substance use disorders are treated (e.g., Veterans Affairs or state hospitals). Thus, our subjects were also more highly educated and had higher rates of recent employment than is typical of persons seeking treatment for substance use disorders. These group and setting characteristics may explain the high rate of borderline personality disorder and low rate of antisocial personality disorder that we found.

Nonetheless, our results suggest that personality psychopathology other than antisocial may be considerable in certain patients with substance use disorders. Specifically, borderline personality disorder was shown to be associated with both alcohol and nonalcohol substance use disorders. Additional productive steps would be to clarify the developmental sequence of substance use problems and personality problems over time, attempting to tease apart cause and effect, as well as to identify general and specific risk factors for both types of psychopathology.