In clinical settings, many psychotic patients receive schizoaffective diagnoses and are treated with combinations of antipsychotic, thymoleptic, and/or antidepressant drugs. For example, 19% of 6,000 surveyed inpatients in New York State psychiatric hospitals were diagnosed as schizoaffective, and most of these were being treated with such drug combinations (W. Tucker, personal communication, March 1997). However, empirical data provide relatively little guidance in selecting treatment for these patients. One problem for both clinicians and researchers is that current diagnostic categories for these patients are neither highly reliable nor predictive of response to treatment. In this article we briefly discuss relevant diagnostic issues and then review available treatment studies, with an emphasis on controlled trials.

DIAGNOSIS OF PATIENTS WITH CONCURRENT SCHIZOPHRENIC AND MOOD SYMPTOMS

Kraepelin

(1) divided functional psychoses into dementia praecox and manic-depressive psychosis, but his rich clinical examples included many patients with mixed features. Kasanin

(2) proposed the term “schizoaffective psychosis” for patients with schizophrenic and affective symptoms, but he described an acute, confusional psychosis that differs from current definitions. A number of researchers developed criteria for schizoaffective disorders

(3–

8), generally finding a long-term outcome that was better than in schizophrenia but worse than in affective psychoses

(5). The Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)

(9) were the first to achieve widespread acceptance among researchers. Schizoaffective disorder was defined as the acute co-occurrence of a full mood syndrome (depression and/or mania) and one of a set of “core schizophrenic” symptoms, such as bizarre delusions, first-rank symptoms, or nearly continuous hallucinations.

The RDC were intended to facilitate study of diverse diagnostic definitions. Distinctions were made between schizoaffective depressed versus manic and chronic versus nonchronic subtypes. Another critical distinction was between the mainly schizophrenic subtype, requiring persistence of psychosis for more than a week (or poor premorbid functioning), and the mainly affective subtype, with no persistence of psychosis for more than a week (and good premorbid functioning). This distinction was based on clinical evidence that persistence of psychosis predicted poor response to mood disorder treatments

(8). In a number of well-designed family studies, relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, and of patients with mood disorders were found to have increased rates of mood disorders but not schizophrenia in comparison with control families. There was an increased prevalence of schizophrenia in the relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, and of patients with schizophrenia

(10,

11), although one study showed no difference in the risk of schizophrenia in relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, compared with those of patients with the affective subtype

(12). Patients with the affective subtype also appeared to show greater response to mood disorder treatments (see below). These data tended to favor considering schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, to be closely related to schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, to be closely related to mood disorders.

Therefore, in DSM-III-R (and subsequently DSM-IV), patients with RDC schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, were defined as having mood psychoses with non-mood-congruent features. Schizoaffective disorder was defined as a modified version of RDC schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype: co-occurrence of schizophrenic and mood syndromes, with persistence of psychosis for 2 weeks after remission of prominent mood symptoms. However, one issue had never been addressed by the RDC or RDC-based research: what diagnosis should be given when there are periods meeting criteria for schizoaffective disorder and others resembling schizophrenia? In the absence of relevant research data, a rather subjective criterion was developed; schizophrenia was to be diagnosed if mood syndromes were not present for a substantial part of the psychotic illness.

Despite these efforts to clarify schizoaffective disorder as a clinical diagnosis, it has proven difficult to diagnose the disorder reliably. In the initial study of the RDC with the use of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia

(13), good interrater reliability (kappa=0.73–0.86) was demonstrated for schizoaffective disorder when schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, and schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, were combined into a single category, but this study has limited relevance to current criteria, since the RDC do not require making a judgment about the lifetime duration of mood syndromes in relation to schizophrenic symptoms, and the reliability of judging the persistence of schizophrenic symptoms within a single episode (affective subtype versus schizophrenic subtype) was also not determined. The major test-retest reliability study of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(14) found moderate reliability for schizoaffective disorder (kappa=0.63), similar to that for schizophrenia (kappa=0.65). However, the base rate for schizoaffective disorder was only 6%, and only two of five sites had enough patients with schizoaffective disorder to calculate site-specific reliability (kappa=0.43 at one site, and kappa=0.76 at the other). In the most extensive study to date

(15), patients were interviewed by two different research clinicians no more than 3 weeks apart after the clinicians had had extensive training with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies with the use of DSM-III-R criteria. Interrater reliability for schizoaffective disorder was poor (kappa=0.37), and the most frequent disagreement was about schizoaffective disorder versus schizophrenia, rather than schizoaffective disorder versus mood disorder.

Schizoaffective disorder is also sometimes defined quite differently across studies. There are family study investigators who assign a schizoaffective disorder diagnosis if a single psychotic exacerbation has included a full mood syndrome (“once schizoaffective disorder, always schizoaffective disorder”), or only if all psychotic exacerbations have included a full mood syndrome (“once schizophrenia, always schizophrenia”), or on the basis of judgments of a preponderance of mixed episodes (e.g., the study by the National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH] Genetics Initiative [15] adopted an additional criterion for schizoaffective disorder: that mood disorder be present for 30% of the periods of psychosis, including neuroleptic treatment periods).

In our experience, diagnostic judgments are often complicated by the difficulty of obtaining the information needed to apply these imprecise diagnostic criteria. Patients tend to overstate past depressive symptoms and understate past psychosis, as demonstrated by 2-year follow-up interviews in the NIMH Collaborative Study of Depression (J. Endicott, personal communication, May 1998). Family members seldom ask patients direct questions about psychosis during periods of relative remission, and standards of documentation of specific symptoms are generally low in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The assessment of current and past mood symptoms can also be confounded by uncertainty about the effects of negative symptoms of schizophrenia, neuroleptic treatment (such as akinesia and akathisia), substance abuse, stressful life events, and demoralization. In clinical practice, schizoaffective disorder diagnoses are probably even less consistent than in research studies. Many clinicians fail to assess the relative persistence of psychotic and mood symptoms between acute episodes, and others expand schizoaffective disorder to include chronic psychosis with a few prominent mood symptoms, as well as mood disorders with a severely psychotic acute presentation.

The relationship between schizophrenia and depressive symptoms is particularly problematic. In a careful follow-up study, Martin et al.

(16) found that up to 60% of patients with stable, long-term diagnoses of schizophrenia reported an episode of major depression at some point. Others have estimated that about 25% of patients with schizophrenia may experience depression

(17,

18). Since the DSM-III-R criteria for schizoaffective disorder were adopted, two family studies

(12,

19) have also reported an increased risk of major depression (but not mania) in relatives of schizophrenic patients.

In the light of these considerations, the clinician should bear in mind that the research literature on treatment of schizoaffective disorder can only be used as a guide if a given study’s approach to diagnosis or assessment is carefully considered, and that the research evidence is an imperfect guide given the poor reliability of schizoaffective disorder diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

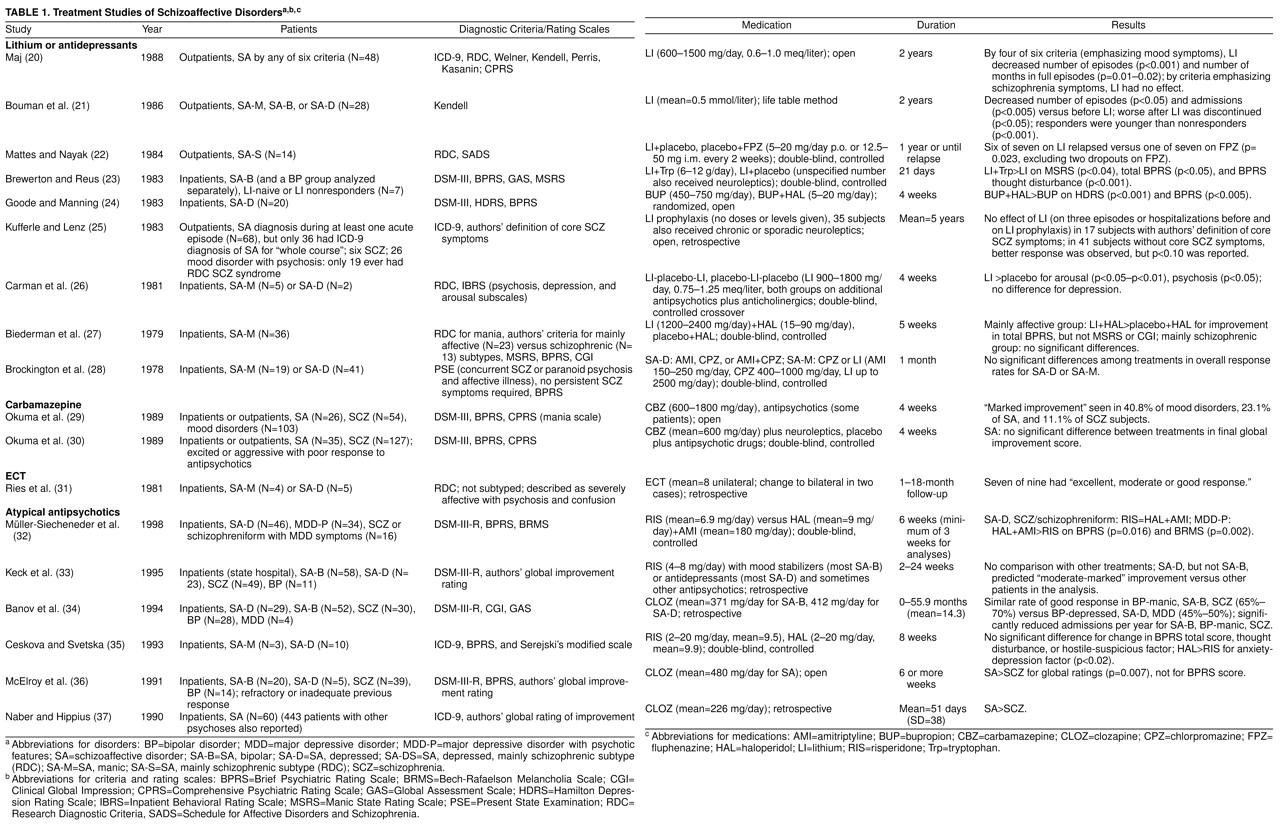

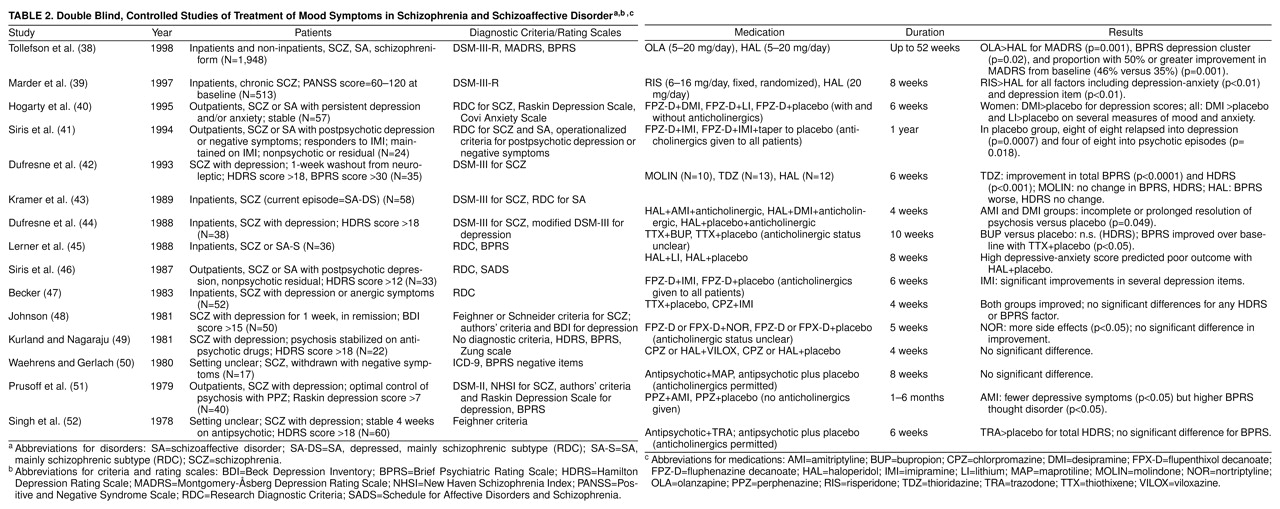

On the basis of this review, we offer the following conclusions, which should be considered highly tentative given the dearth of controlled data, particularly regarding the newer antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers.

1. The diagnostic distinction most predictive of response to pharmacological treatment, according to available controlled studies, is between mood disorders with psychotic features and disorders in which psychosis persists in the absence of mood syndromes (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder). Thus, the evaluation of patients with concurrent psychotic and mood symptoms should include a thorough review of the entire course of illness to determine whether a primary mood disorder with psychotic features is present, and if so, vigorous treatment efforts will be based on the literature on mood disorders rather than on the studies reported here. By contrast, there is little evidence that the distinction between DSM-IV schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders is substantially predictive of response to available treatments, and indeed the reliability of this distinction has not been clearly established.

2. For patients with acute exacerbations of schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia with depressive symptoms, controlled data suggest that antipsychotic drugs are the best available treatments and that adjunctive antidepressants are of no benefit or may even have a negative effect. Atypical antipsychotics may prove advantageous. Several large open studies (but not the one controlled study to date) suggested superiority of these agents for schizoaffective patients, two controlled studies demonstrated an advantage in alleviating depressive symptoms in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients, and one open study reported reduced suicidality in schizophrenic patients treated with clozapine. Thus, the data are most supportive of optimization of neuroleptic treatment, including minimization of extrapyramidal symptoms and trials of atypical antipsychotics, rather than routine use of adjunctive antidepressants. Clinicians should recognize that while antidepressants may be helpful to individual patients, their use is not well supported by controlled studies. We suggest that such trials should be discontinued if there is no significant improvement. And when improvement is observed, there should be an attempt to monitor the patient both on and off the adjunctive treatment to determine whether it is predictably associated with improvement or whether the initial improvement might be better explained by the extra time on the original antipsychotic treatment regimen, variation in the course of illness, variation in substance abuse, or other factors.

3. There is substantial evidence, however, to support trials of adjunctive antidepressants in schizophrenic and schizoaffective outpatients who have new or continued full major depressive syndromes after psychosis has stabilized. We again suggest that antidepressants be discontinued if psychosis worsens or if there is no improvement after adequate trials, and that patients who do improve be observed while on and off antidepressants to determine whether their continued use is warranted.

4. There is mixed evidence concerning addition of antidepressants for depressive symptoms (as opposed to syndromes) in schizophrenic outpatients. We tentatively conclude that such trials are not consistently beneficial and that there may be some risks (worsening of psychosis has sometimes been observed). We suggest that clinicians give careful consideration to other possible interventions (optimization of neuroleptic treatment, use of atypical antipsychotics, intervention for psychosocial stressors, assessment and reduction of substance abuse), avoid routine use of antidepressants for complaints of depression, and evaluate the outcome of such trials by observing patients when they are both on and off antidepressants.

5. Adjunctive use of lithium for depressive symptoms in schizophrenia has not received sufficient study to draw conclusions. There are no studies of addition of lithium for specific mania-like symptoms. There is currently no empirical basis for the widespread long-term administration of lithium and other thymoleptics to patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. We urge greater skepticism and caution about the use of these agents in these patients pending further research.

6. There are few controlled studies of the newer thymoleptic agents such as sodium valproate or of the newer antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients.

We note that the American Psychiatric Association’s recent

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia (59) differs substantially from our conclusions and recommendations in one area. The

Guideline concludes that there is some support for use of lithium in both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Two studies of schizophrenic patients are cited. Small et al.

(60) studied 14 schizophrenic and eight schizoaffective patients in a balanced crossover design (two 4-week periods on adjunctive lithium and two on placebo); there were 15 completers, and of multiple statistical comparisons, there was one with an uncorrected p value of <0.05; i.e., this was a study with negative results. Growe et al.

(61) studied six schizophrenic and two schizoaffective patients in a similar crossover design and observed an advantage of lithium at p<0.01 for one of eight rating scales; i.e., this was also a study with negative results and too few subjects to support strong conclusions. Furthermore, there are reasons for the dearth of controlled data in the years since those studies were published: 18 years: many clinical research investigators have observed multiple patients with schizophrenia who have not responded to adjunctive lithium, so there is limited enthusiasm for initiating new large studies to resolve the issue.

The

Guideline refers to four studies as evidence of the efficacy of lithium in schizoaffective disorders. Johnson

(62) and Prien et al.

(63) used older diagnostic criteria, which would have included many patients with primary mood disorder. Carman et al.

(26) studied just seven patients, and Biederman et al.

(27) observed improvement in patients with schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective type (i.e., mood disorder) rather than schizoaffective disorder, mainly schizophrenic type, as defined by the RDC. Evidence from controlled studies, as discussed earlier, fails to support the use of lithium in these patients.

The most recent review of pharmacological treatment of schizoaffective disorder

(64) discussed some of the studies reviewed here and concluded similarly that there were no controlled data to support combination neuroleptic-thymoleptic treatment. The authors also took a more positive view toward the uncontrolled data favoring such combinations, whereas we have suggested that there are few data relevant to patients who would be considered schizoaffective by current DSM-IV criteria (rather than the RDC). They suggested that uncontrolled data favored the use of atypical neuroleptics, and this conclusion has generally been supported by subsequent controlled studies of mood symptoms associated with schizophrenia, but specifically for schizoaffective disorder, as discussed above.

In conclusion, controlled data suggest that typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs are most effective for the acute and maintenance treatment of patients with schizoaffective disorders and of schizophrenic patients with mood symptoms. Optimization of antipsychotic treatment is thus more likely to be effective than the routine use of adjunctive antidepressants or mood stabilizers. The one exception is that the use of antidepressants is well supported in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients who present with a full depressive syndrome after stabilization of psychosis. There are few if any data to support the use of antidepressants or thymoleptics for subsyndromal depressive symptoms or for depression during acute schizophrenic or schizoaffective exacerbation.

Why, then, are these agents so widely prescribed for schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients? The major factor is probably that suboptimal response to antipsychotic drugs remains common, while depressive and manic symptoms are common in patients whose long-term course otherwise suggests schizophrenia, so antidepressants and thymoleptics often offer the physician the only justifiable option for improving outcome. Also, thymoleptics and the newer antidepressants have favorable side effect profiles, so their risks usually seem minimal compared with the possible benefits of reducing distressing mood symptoms, and it may seem easier to add one of these drugs than to risk substituting another antipsychotic drug for one that has been at least partially effective. We suggest, however, that there is little controlled evidence supporting this practice (except for antidepressants for postpsychotic major depressive syndrome). Until more controlled studies are available, the most rational approach would be to make substantial efforts to optimize antipsychotic drug treatment (including trials of atypical antipsychotics) before adding antidepressants or thymoleptics. Trials of the latter agents might best be viewed as humanitarian “single-subject experiments,” so the adjunctive drug should be discontinued if there is no response, and an apparent response can best be evaluated by stopping and restarting the adjunctive agent one or more times while monitoring relevant target symptoms.