The efficacy of both exposure therapy and serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has been well established in placebo-controlled studies. Although many have benefited from those treatments, 10% to 40% of patients do not respond to an adequate trial

(1,

2). However, the existing literature on reliable predictors of treatment outcome in OCD is sparse and inconsistent. The predominance of compulsive symptoms, cleaning rituals, earlier age at onset, longer illness duration, and chronic course was found to be associated with poor response to serotonin reuptake inhibitors in some studies

(3–

5). In two retrospective studies, the presence of schizotypal personality was a negative outcome predictor for pharmacological

(6) and behavioral

(7) treatments. The presence of schizotypal, avoidant, and borderline personality disorders predicted poorer treatment outcome with clomipramine

(8). However, in one study the presence of a personality disorder was not related to improvement with fluoxetine

(9). Similarly, others found that the presence of various personality disorders was not related to outcome with behavior therapy

(10).

The symptoms of OCD are heterogeneous, so that any given patient with this diagnosis may present with only one or, more commonly, many of these symptoms

(11). Studies are, however, conflicting about whether any particular subtype of OCD is easier to treat or more likely to benefit from a particular treatment. For instance, there is some evidence that OCD patients with comorbid chronic tic disorders, and possibly those with concurrent psychotic spectrum disorders, are more likely to require the addition of a neuroleptic medication to treatment with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor

(12). Recently, Jenike et al.

(13) reported that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) may be preferentially useful for the treatment of symmetry and unusual somatic obsessions. Similarly, the presence of symmetry obsessions, ordering compulsions, and hoarding rituals predicted better response in refractory patients treated with cingulotomy

(14). Patients with cleaning and checking symptoms may respond best to exposure methods, but other subgroups, such as patients with ordering compulsions, hoarding rituals, or slow patients, have rarely been included in trials of behavior therapy

(15). Some studies have suggested that patients with washing symptoms may do better with exposure therapy

(16,

17) and worse with serotonin reuptake inhibitors

(3,

5). Checking rituals predicted poorer outcome in some behavior therapy studies

(16,

18), but others have found no differences in treatment response between patients with washing and checking symptoms

(19). In addition, anecdotal evidence suggests that patients with predominantly obsessive symptoms (ruminations) might respond better to medication and worse to conventional behavioral techniques, but no empirical evidence is available.

RESULTS

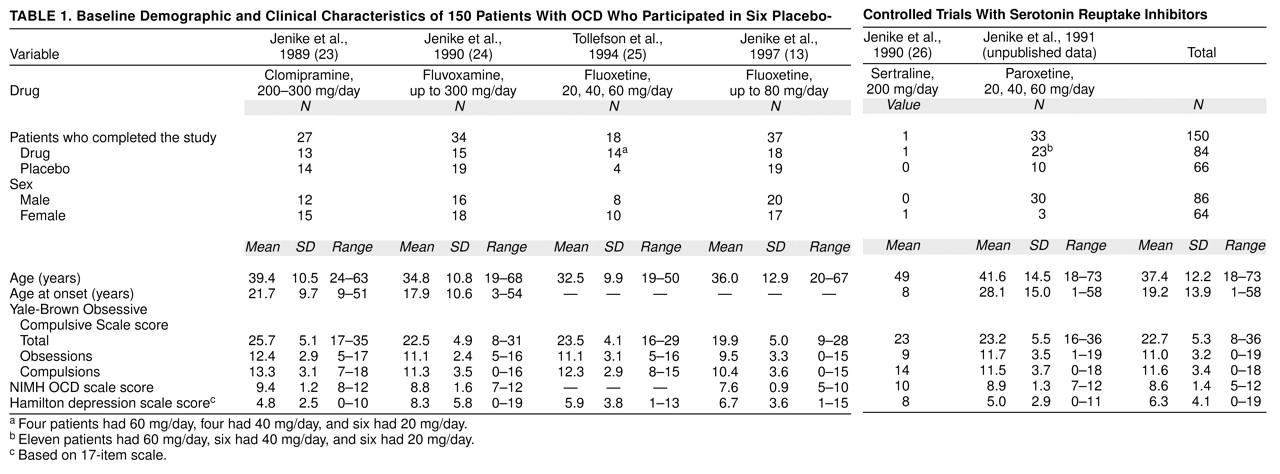

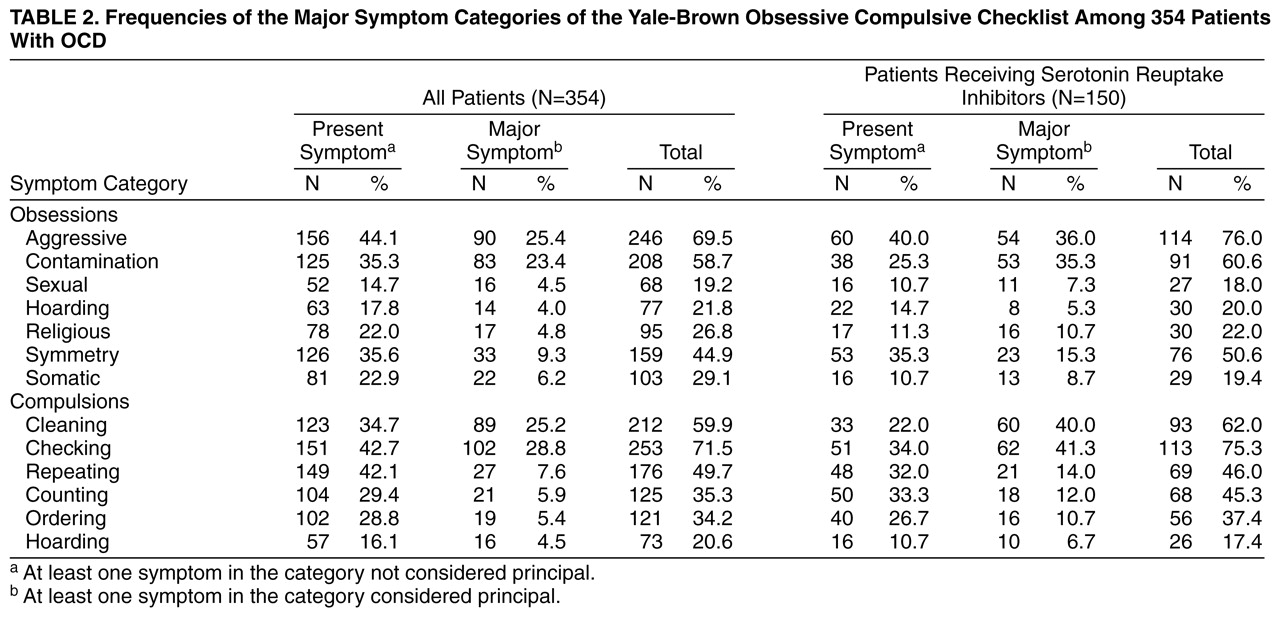

Frequencies of the major symptom categories of the Yale-Brown symptom checklist in our study group are listed in

table 2. As would be expected on the basis of previous studies

(32), the most frequent specific categories included obsessions about harm, contamination, and symmetry, as well as checking, cleaning, and repeating compulsions.

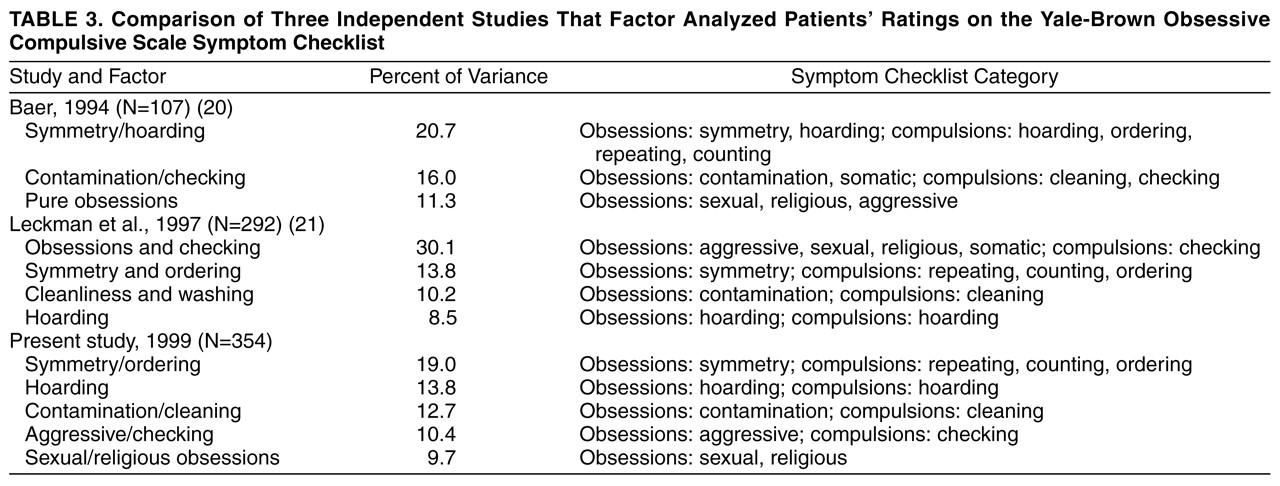

The principal components analysis yielded a five-factor solution. The five factors accounted for 65.5% of the total variance and were named as follows: symmetry/ordering, hoarding, contamination/cleaning, aggressive/checking, and sexual/religious obsessions. The first factor accounted for 19% of the variance and included symmetry obsessions and ordering, counting, and repeating compulsions; loadings ranged from 0.41 to 0.82. The hoarding factor accounted for 13.8% of the variance and included hoarding obsessions and compulsions, both with a loading of 0.90. The third factor (12.7% of the variance) included contamination obsessions and cleaning/washing compulsions. Both symptom categories had a loading of 0.91 on this factor. The aggressive/checking factor explained a 10.4% of the variance and included aggressive obsessions and checking compulsions, with loadings over 0.82. The fifth factor accounted for 9.7% of the total variance. Sexual and religious obsessions had strong loadings (>0.71) on this factor. The five-factor solution is highly congruent with other factor-analytic studies following a comparable methodology (

table 3).

After Bonferroni correction for 55 tests (0.05/55=0.0009), the symmetry/ordering dimension was robustly associated with the compulsive need to know (r=0.20; for this and the following correlations, N=354, p<0.0009), fear of not saying the right thing (r=0.24), lucky numbers (r=0.25), and touching compulsions (r=0.20). The need to know was also associated with higher scores on hoarding (r=0.22). Fear of saying certain things (r=0.22), intrusive images (r=0.24) and sounds (r=0.20), lucky numbers (r=0.23), colors with special significance (r=0.20), and the need to tell, ask, or confess (r=0.28) were all positively associated with higher scores on sexual/religious obsessions.

After correction for multiple tests (0.05/15=0.003), the symmetry/ordering dimension was significantly correlated with Yale-Brown scale total score (r=0.16, N=354, p<0.003) and compulsions subscale score (r=0.22, N=354, p<0.003) but not with obsessions subscale score (r=0.04, N=354). The contamination/cleaning dimension was also significantly correlated with Yale-Brown scale total score (r=0.20, N=354, p<0.003) and compulsions subscale score (r=0.23, N=354, p<0.003) but not with obsessions subscale score (r=0.10, N=354).

Men (N=190) scored significantly higher than women (N=164) on symmetry/ordering (men: mean=0.12, SD=1.09; women: mean=–0.14, SD=0.85) (Mann-Whitney U=13598.5, p=0.03). Women scored higher than men on contamination/cleaning (men: mean=–0.09, SD=1.00; women: mean=0.10, SD=0.99) (Mann-Whitney U=13642.5, p=0.04) and aggressive/checking (men: mean=–0.11, SD=0.96; women: mean=0.12, SD=1.03) (Mann-Whitney U=13429.5, p=0.02).

For the 172 patients for whom age at onset was available, it was significantly negatively correlated with symmetry/ordering (r=–0.16, N=172, p=0.02), aggressive/checking (r=–0.18, N=172, p=0.01), and sexual/religious obsessions (r=–0.21, N=172, p=0.005). In analyses by gender, age at onset was correlated with symmetry/ordering only in men (r=–0.26, N=90, p=0.01) and with aggressive/checking (r=–0.25, N=82, p=0.01) and sexual/religious obsessions (r=–0.31, N=82, p=0.004) only in women.

Forty-six (26.6%) of 173 patients met criteria for a lifetime history of chronic motor or vocal tic disorders or both. They were compared with the 127 patients without that diagnosis on all demographic and clinical variables. Male patients were significantly more frequent in the tic group (N=30 [65.2%] of 46) than in the nontic group (N=59 [46.5%] of 127) (χ2=4.76, df=1, p=0.03). Groups did not differ on age. Patients with comorbid tic disorders had a significantly earlier age at onset (tic group: mean=12.51, SD=7.95; nontic group: mean=16.90, SD=10.10) (F=4.05, df=1, 90, p=0.04) and scored higher on the Yale-Brown scale total (tic group: mean=23.65, SD=6.89; nontic group: mean=20.89, SD=6.57) (F=5.77, df=1, 171, p=0.01) and compulsions subscale (tic group: mean=11.73, SD=4.25; nontic group: mean=10.08, SD=4.32) (F=4.98, df=1, 171, p=0.02). Patients with tics scored significantly higher on symmetry/ordering (tic group: mean=0.02, SD=0.83; nontic group: mean=–0.36, SD=0.81) (F=7.52, df=1, 171, p=0.006). Separately by gender, men with tics scored significantly higher on symmetry/ordering (tic group: mean=0.12, SD=0.89; nontic group: mean=–0.34, SD=0.85) (F=5.89, df=1, 87, p=0.02). Women with tics scored significantly higher than women without tics on the Yale-Brown total (tic group: mean=24.81, SD=6.93; nontic group: mean=20.67, SD=6.37) (F=5.28, df=1, 82, p=0.02) and obsessions subscale (tic group: mean=12.68, SD=3.36; nontic group: mean=10.44, SD=3.61) (F=5.12, df=1, 82, p=0.03).

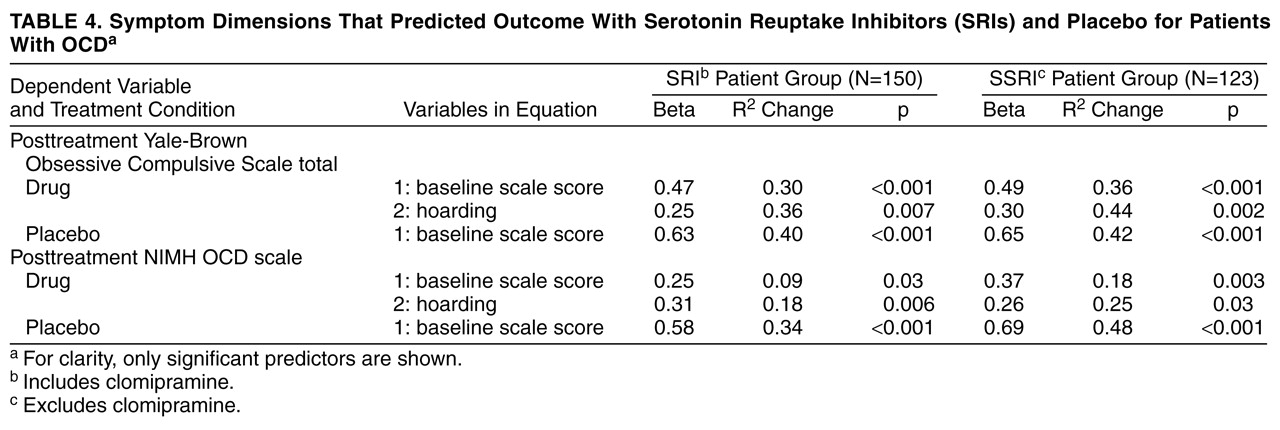

Patients treated with serotonin reuptake inhibitors were significantly improved after treatment on all measures as compared to placebo-treated patients, after adjustment for initial severity scores (Yale-Brown scale: beta=0.19, R2=0.35, p=0.004; NIMH scale: beta=0.23, R2=0.21, p=0.001). This pattern was also observed after the exclusion of the clomipramine study (Yale-Brown scale: beta=0.23, R2=0.39, p=0.001; NIMH scale: beta=0.15, R2=0.29, p=0.05).

Regression analyses showed that severity at baseline predicted posttreatment severity for drug and placebo conditions on all clinical measures. After control for symptom severity, higher scores on the hoarding dimension predicted poorer outcome at posttreatment on all outcome measures. No predictors of placebo response were obtained. Exclusion of clomipramine recipients did not modify the overall results, suggesting a cross-serotonin reuptake inhibitor effect.

Table 4shows the beta coefficients and the proportion of variance in the dependent variables accounted for by the independent variables (R

2 change).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report a relationship between factor-analyzed symptom dimensions and response to serotonin reuptake inhibitors in OCD. Previous research had failed in the attempt to relate OCD symptom subtypes to clinical and demographic variables and to treatment outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The five dimensions obtained in the present study are consistent with prior factor-analytic research that used a similar methodology

(20,

20) and were found to be differentially related to sex, age at onset, comorbid tic-related disorders, and response to serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

The first dimension was named symmetry/ordering and had high factor loadings from symmetry obsessions and ordering, counting, and repeating compulsions. As in previous studies (20, 21), patients with comorbid tic disorders scored significantly higher on this factor. As many as 27% of the patients met criteria for a lifetime history of chronic motor or vocal tics or both; this finding is consistent with previous research

(33). These patients had an earlier age at onset, and most were men. In fact, analyses by gender revealed that only male patients with tics scored significantly higher on symmetry/ordering. Scores on this dimension were correlated with total score on the Yale-Brown scale and the compulsions subscale score but not with the obsessions subscale score. Similarly, Holzer and associates compared the phenomenological features of 35 OCD patients with comorbid tics to 35 age- and sex-matched OCD patients without tics and found that patients with tics had more touching, tapping, rubbing, blinking, and staring rituals and fewer cleaning rituals but did not differ on obsessions

(34). This tic-like factor corresponds to Janet’s classic description of patients who were tormented by an inner sense of imperfection and felt that their actions were never completely achieved to their satisfaction

(35). This feeling of incompleteness is also experienced by patients with Tourette’s syndrome and trichotillomania

(32). It also corresponds to the form of OCD that is thought to be genetically related to Tourette’s syndrome, as family and genetic data have suggested

(36). McDougle and associates found that serotonin reuptake inhibitor monotherapy was less effective in OCD patients with comorbid chronic tics than in those without tics

(37) and that those patients may benefit from the combination of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a dopamine antagonist

(12). In light of these findings, it would be expected that symmetry/ordering symptoms would be related to poorer outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Nonetheless, in the current study, this dimension was unrelated to treatment outcome. A putative explanation is that comorbid tic disorders were entry exclusion criteria for the studies included in our predictors analysis.

The second factor, termed “hoarding,” had high factor loadings from hoarding/saving obsessions and hoarding compulsions. Baer’s original factor analysis

(20) grouped this factor with symmetry/ordering. In fact, correlation analysis showed that these two factors were the most intimately linked. Hoarding symptoms were present in as many as 20% of the patients and were a major problem for about 5% of them, as previously reported

(32). Different accounts of the hoarding phenomenon in OCD are evident. First, hoarding has been seen as an abnormal personality characteristic, and it constituted a diagnostic criterion for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in DSM-III-R. Second, from an ethological perspective, hoarding symptoms can be regarded as inappropriately released fixed-action patterns

(38). Third, hoarding can be conceptualized as the consequence of dysfunctional beliefs formed by prior learning experiences

(39).

Hoarding obsessions and compulsions predicted poor response to serotonin reuptake inhibitors, regardless of the outcome measure used or the inclusion of the clomipramine trial. In our principal components analysis, somatic obsessions also loaded on this factor (loading=0.35) but were not listed because we set 0.40 as the cutoff point. This is especially interesting in light of the results of the study by Jenike et al., in which symmetry, hoarding, ordering, and unusual somatic obsessions were significantly more common in patients who responded to phenelzine than in those who responded to fluoxetine

(13). Moreover, one study found that presence of symmetry obsessions, ordering compulsions, and hoarding rituals predicted better response in patients treated with cingulotomy

(14). Therefore, hoarding, and perhaps somatic obsessions, which predicted poor outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this study, might better respond to alternative treatments such as MAOIs or cingulotomy. This statement is speculative and requires further examination.

Factors 3 and 4 correspond to the classic contamination and checking dimensions of the Maudsley Obsessional Compulsive Inventory

(40) and, as in previous studies

(32), were the most frequent symptoms in our group. Finally, the sexual/religious obsessions dimension corresponds to the pure obsessions factor in Baer’s study

(20). These OCD symptoms are usually termed “pure obsessional disorder” when they appear in isolation

(32).

The rationale for a dimensional model of OCD, according to which certain symptom dimensions—that, in most cases, coexist in the same patient—are differentially related to demographic and clinical characteristics and treatment response, reflects the existing contemporary neurobiological models for the disorder

(22). It has been hypothesized that the heterogeneous phenomenology of OCD could be mediated by neuroanatomically different structures

(41). The striatum has a well-described topographic organization with respect to its afferent cortical connections and connections to other subcortical structures, as well as cytoarchitecture and neurotransmitters

(42). According to the model, the symptoms of OCD would parallel the topography of dysfunction within the corticostriatal network. The extent and location of the dysfunction would determine the heterogeneous clinical picture of OCD. This would explain, for example, why different symptoms can occur either alone or in combination with others in any given patient, the relationship between certain symptoms and comorbid diagnoses, and the differential treatment response. The model still has to explain why the clinical manifestations of OCD change over time, as suggested by Rettew et al.

(43) in the only published study directly addressing this issue. These authors followed up 79 children and adolescents with OCD over 2 to 7 years and found that none maintained the same constellation of symptoms from initial assessment to follow-up. Analogous data have yet to be published for adults with OCD.

Possible limitations of the present study need to be considered. The retrospective acquisition of information from case records is not ideal, but histories were comprehensive and followed a semistructured format. Additional prospective research on outcome predictors is required both for behavior and drug therapies. We pooled data from different SSRIs. It may be premature to conclude that differences in outcome are attributable to symptom dimensions when there has been no control for which SSRI was given to which patient. Nonetheless, power was inadequate to analyze each drug separately. Another direction for future study will be to develop a self-rated version of the symptom checklist in order to use it as a standardized instrument in OCD research. Further research on genetics, neuroimaging, and neuropsychology is warranted to confirm the differential involvement of distinct neural elements with the identified symptom dimensions. It is possible that OCD may constitute a label that researchers and clinicians use to name multiple disorders with multiple etiologies, rather than a homogeneous disease. The factor-analytic approach used in the present study and in others has identified meaningful symptom dimensions to help guide future research.