Individuals with a psychotic disorder have consistently been shown to have very high rates of smoking, ranging from 70% to 88%

(1 –

3), compared with approximately 50% for psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia and 25% for the general population

(4) . Consequently, there is cause for concern because of the serious financial and health costs. It has been estimated that smokers with schizophrenia in the United States spend just over one-third of their weekly income on cigarettes

(5) . Smokers with psychiatric illnesses are less likely to stop smoking compared with individuals without psychiatric illnesses, probably because of higher levels of nicotine dependence

(1) . Smoking-related diseases may contribute to reductions in life expectancy, with the most common cause of death among people with schizophrenia being ischemic heart disease

(6) . Smokers with a psychotic disorder may smoke cigarettes in order to alleviate negative symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, or medication side effects

(7) in addition to smoking for many of the same reasons as smokers without a psychiatric illness

(3) . Paradoxically, smokers with a psychotic disorder have been reported to experience increased psychiatric symptoms, number of hospitalizations, and a need for higher medication doses

(8) .

Several small trials have been conducted among smokers with schizophrenia, using combinations of either nicotine replacement therapy

(9,

10) or bupropion with group interventions

(11 –

13) . Such interventions have been shown to be useful among smokers without a mental illness

(14) . However, available treatment trials for smokers with schizophrenia have been criticized on methodological grounds, including heterogeneous samples, small sample sizes, and lack of defined interventions and comparison groups, with cessation being achieved among very few participants and recommendations that future smoking cessation interventions be evaluated using more rigorous methodology

(15) . There is also a need to assess smoking outcomes other than cessation

(16) .

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of individually administered motivational interviewing and cognitive behavior therapy plus nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation or reduction among individuals with a psychotic disorder and, second, to evaluate impact on psychiatric symptoms. It was hypothesized that a greater proportion of participants receiving motivational interviewing/cognitive behavior therapy plus nicotine replacement therapy would report smoking cessation or reduction, relative to a routine care control condition.

Results

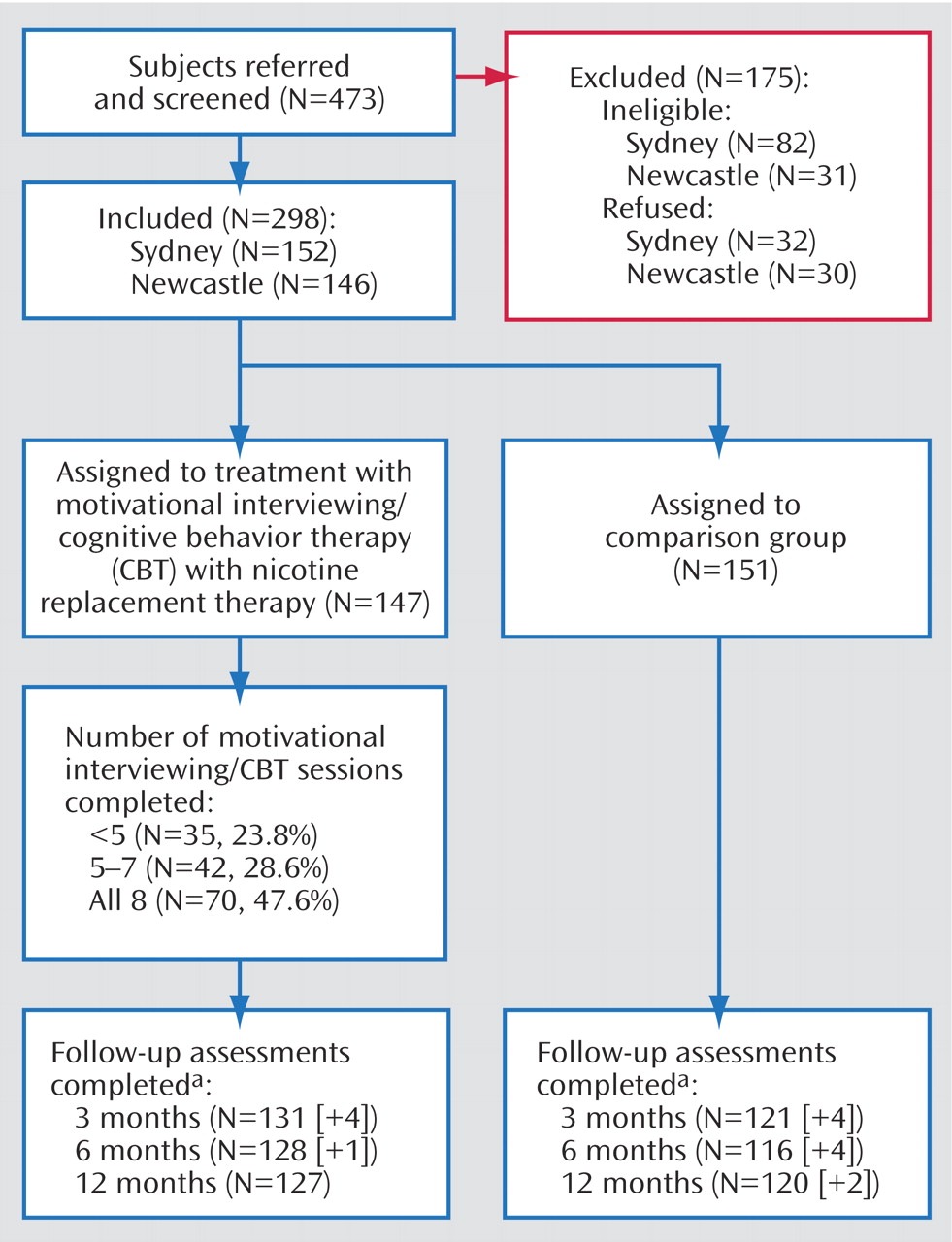

Overall recruitment and attrition profiles are presented in

Figure 1 . Of the 473 individuals referred to the study, 113 were ineligible (23.9%), while an additional 62 (13.1%) declined, leaving a recruited sample of 298 regular smokers with an ICD-10 psychotic disorder.

Characteristics of Participants at the Pretreatment Assessment

As detailed elsewhere

(19), there were 156 men and 142 women recruited to the study, with an average age of 37.24 years (SD=11.09 years). The typical participant was Australian born (84.9%), single (65.8%), receiving welfare support (95.6%), and they had not completed senior high school (64.8%). Just over one-half of the study group (56.7%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a schizoaffective disorder. More extensive pretreatment sample characteristics are reported in our earlier article

(19), together with an examination of smoking characteristics and reasons for smoking and quitting.

Attendance at Treatment Sessions and Follow-Up

As shown in

Figure 1, approximately one-half (47.6%) of the treatment group attended all eight treatment sessions, while one-quarter (23.8%) attended less than five sessions. Patterns of follow-up attendance were considered when preparing data sets for analysis. Participants who did not complete their follow-up assessment within the designated time period (i.e., less than one-half of the time interval between follow-ups) were classified as continuous smokers for the intention-to-treat analyses. Only those who completed their follow-up within the designated time period were retained in the nonintention-to-treat analyses. On this basis, eight, five, and two people, respectively, who completed their 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up evaluations, had their nonconforming data excluded from the relevant nonintention-to-treat analyses. The resulting patterns of attendance were very similar across all phases (84.6% [N=252] at 3 months; 81.9% [N=244] at 6 months; and 82.9% [N=247] at 12 months). However, since only two-thirds (65.1%) of the participants attended all follow-up sessions, the major nonintention-to-treat analyses involved comparisons between pairs of time points. There were no significant differences between groups in follow-up attendance patterns.

Overall Changes in Smoking

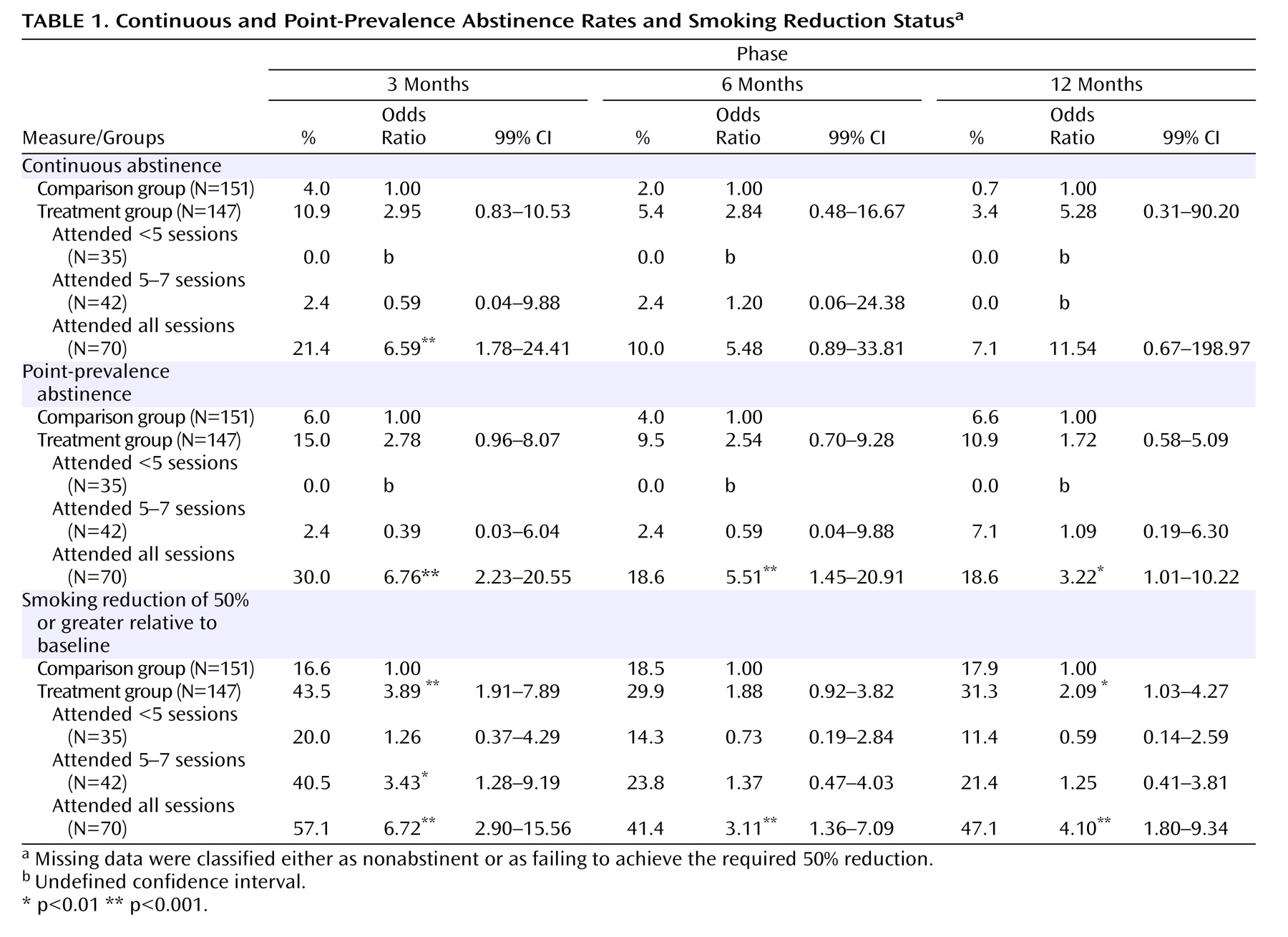

Table 1 displays continuous and point-prevalence abstinence rates and smoking reduction status for the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up assessments. In the intention-to-treat analyses, we found no significant overall differences between the treatment group and comparison group in continuous abstinence or point-prevalence abstinence rates measured at 3-, 6-, and 12-months. However, there was a significant difference in smoking reduction status at 3 months, with 43.5% of the treatment group reducing their cigarette consumption by at least 50% relative to baseline, relative to only 16.6% of the comparison group (odds ratio=3.89, p<0.001). At the subsequent follow-up sessions, approximately 30% of the treatment group and 18% of the comparison group reported comparable reductions, although this difference was only significant at 12 months (

Table 1 ).

Table 1 also reports comparisons between the comparison group and treatment subgroups defined on the basis of their patterns of attendance. There were no baseline differences between these four groups regarding key sociodemographic or clinical variables. Participants who completed all treatment sessions were significantly more likely than the comparison group to have improved at the 3-month follow-up on all three smoking outcome measures (i.e., continuous and point-prevalence abstinence and reduction status). Relative to the comparison group, participants who completed all treatment sessions were also significantly more likely to be abstinent at the 6- and 12-month follow up sessions (point prevalence) and/or to have reduced their consumption by at least 50%. Participants who completed five to seven sessions were also significantly more likely to have decreased their smoking by half at 3 months.

There were no overall differences in abstinence rates or smoking reduction patterns according to medication status upon entry to the study (atypical versus typical antipsychotic medication), nor did medication status impact on the effects observed for treatment session attendance. At each of the follow-up assessments, all but one of the participants who reported that they were abstinent (31 at 3 months, 20 at 6 months, and 24 at 12 months) produced carbon monoxide levels <10 ppm, the exception being one person at 12 months who reported continued high levels of cannabis use. Under the circumstances, this person was classified as abstinent in the analysis, which is in keeping with accepted practice.

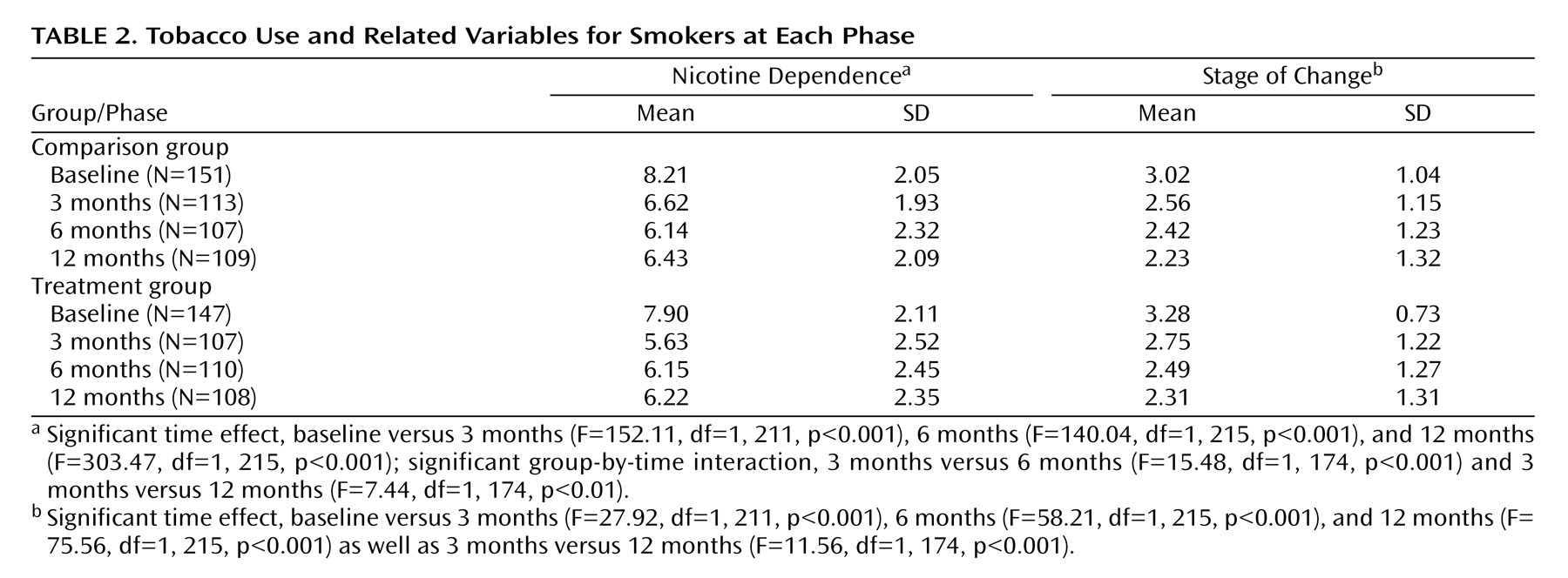

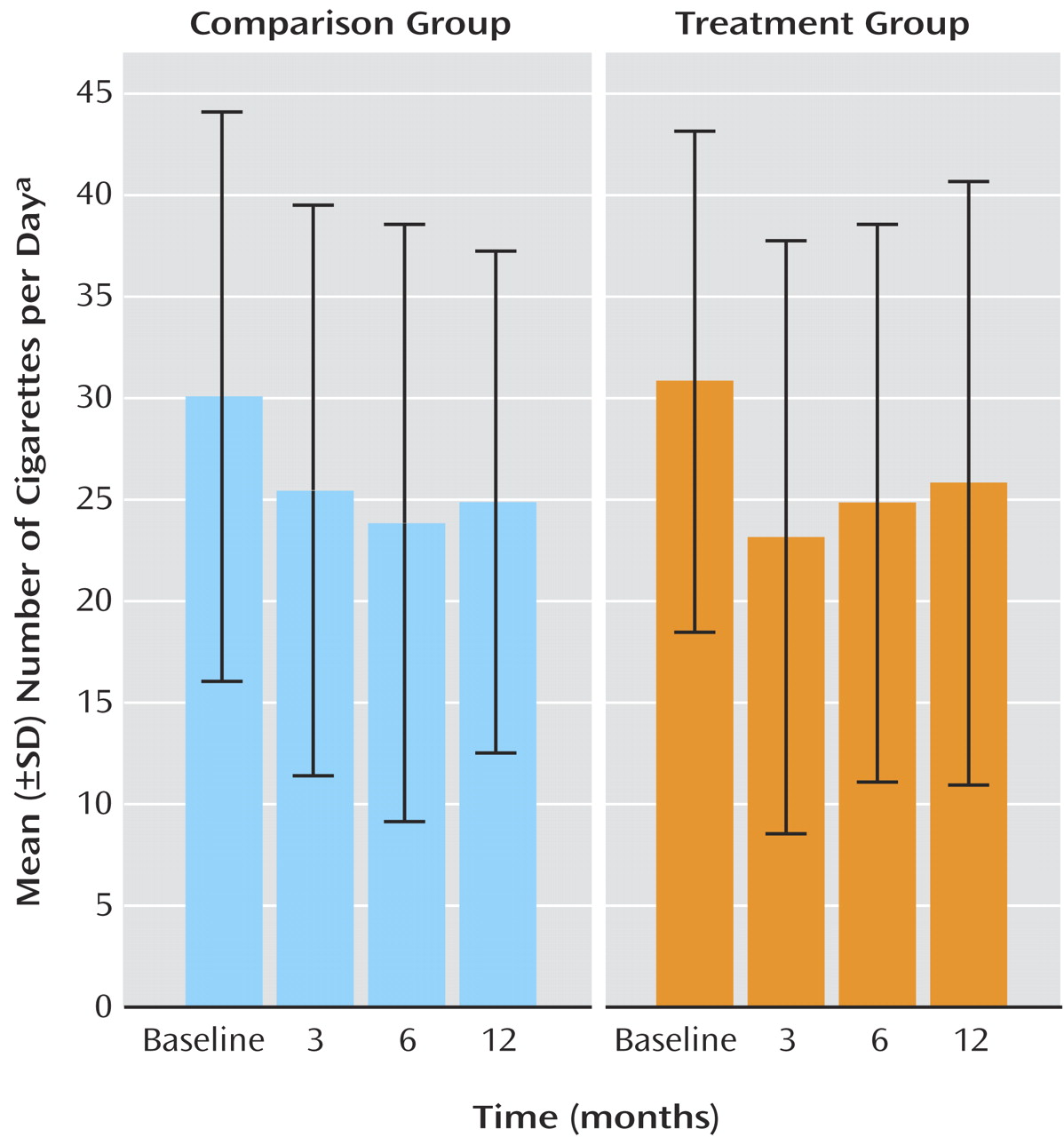

Table 2 and

Figure 2 presents profiles for selected smoking-related variables for current smokers at each phase. For nicotine dependence (Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence scores) and daily cigarette consumption, there were significant reductions from baseline to each of the follow-up sessions. The treatment group also displayed an increase in Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence scores from 3 months to the subsequent follow-up sessions, relative to smokers in the comparison group, whose nicotine dependence tended to decline. For stage of change, continuing smokers reported a significant decrease in motivation to stop smoking at each of the follow-ups, relative to baseline, as well as a significant decrease from 3 months to 12 months.

Patterns of Nicotine Replacement Therapy Use

At each follow-up, participants reported on their nicotine replacement therapy use during the preceding period (including patches and other methods). At 3 months, 29.8% of the comparison group and 84.0% of the treatment group reported nicotine replacement therapy use during the preceding 3 months. Among members of the treatment group who attended less than five sessions, 58.6% reported nicotine replacement therapy use, compared with 89.2% and 92.3%, respectively, of those who attended five to seven sessions and all treatment sessions, which largely reflects the link between nicotine replacement therapy provision and treatment attendance. At 6 months, 22.4% of the comparison group and 37.5% of the treated group reported nicotine replacement therapy use during the preceding period. By 12 months, the reported rates had converged, with 28.3% of the comparison group and 31.0% of the treated group reporting nicotine replacement therapy use during the preceding 6 months. Reported use of nicotine replacement therapy at 3 months was associated with a net reduction of 8.14 cigarettes per day, in that nicotine replacement therapy users (N=137) reported a reduction of 12.25 (SD=16.96) cigarettes per day compared with 4.11 (SD=10.6) for nonusers (N=106) (p<0.001). Among the latter group, those who subsequently reported nicotine replacement therapy use at 6 months also showed a net reduction of 8.28 cigarettes per day, with new nicotine replacement therapy users (N=12) reporting a reduction of 10.42 (SD=13.29) compared to 2.14 (SD=9.15) for continued nonusers (N=76) (p<0.01). Among participants who shifted from nonuse of nicotine replacement therapy at 6 months to nicotine replacement therapy use at 12 months (N=20), there was a reduction of 4.10 (SD=14.34) cigarettes per day, compared with an increase of 0.49 (SD=8.46) among participants who were nonusers on both occasions (N=131), a net difference of 4.59 cigarettes per day, which was not significant (p=0.04).

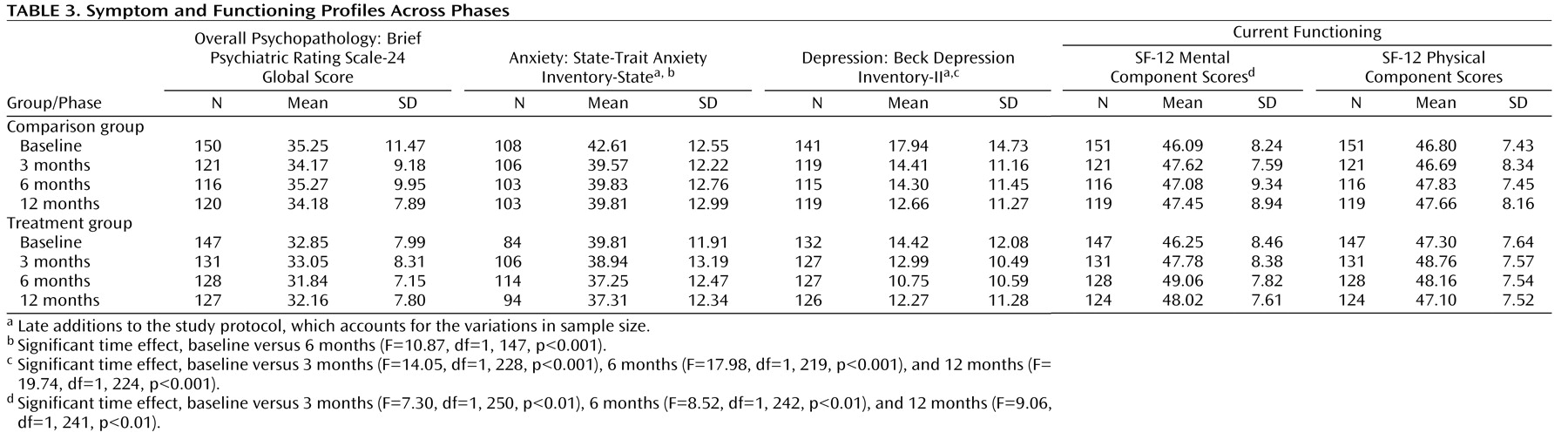

Changes in Symptoms and Functioning

Table 3 presents symptom and functioning profiles across phases. There were no significant differences between groups or across occasions for Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale-24 global scores or Short Form Survey-12 physical component scores. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory state anxiety scores reduced significantly from baseline to 3 months, while Beck Depression Inventory-II depression scores were significantly lower at each of the follow-up sessions relative to baseline. Similarly, baseline SF-12 mental component scores were significantly lower than each of the follow-up occasions, indicative of a general improvement in mental functioning. However, there was no significant group-by-time interaction in the nonintention-to-treat analyses, suggesting that any improvements in symptoms and functioning could not be attributed to specific aspects of the treatment program.

Discussion

The abstinence results are discussed first, followed by consideration of the smoking reduction findings and other potential intervention effects. One of the major findings was that, at all follow-up occasions, a significantly higher proportion of smokers with a psychotic disorder who completed all treatment sessions were currently abstinent, relative to those in the comparison group (point-prevalence rates: 3 months, 30.0% versus 6.0%; 6 months, 18.6% versus 4.0%; and 12 months, 18.6% versus 6.6%). Smokers who completed all treatment sessions were also more likely to have achieved continuous abstinence at 3 months (21.4% versus 4.0%). Moreover, no participants who attended fewer than five treatment sessions reported abstinence at any follow-up point, and very few participants attending five to seven sessions reported that they were abstinent. It appears that if smokers with a psychotic disorder complete all counseling sessions of a smoking cessation intervention (at which nicotine patches are also distributed), then they are more likely to stop smoking than smokers who do not complete those intervention sessions. A similar relationship was also reported in a small, uncontrolled study among smokers with schizophrenia

(9) . Therapy procedures to enhance completion of smoking cessation interventions (e.g., intervention completion contracts, other reinforcement contingencies) may enhance cessation rates in future studies.

As in other studies (e.g.,

9,

10,

12), the overall cessation rate achieved at the end of treatment was modest and below that reported among smokers without a psychiatric illness

(33) . However, the lower cessation rates observed among the current sample are not unexpected, given that people with a chronic mental illness often have higher nicotine dependence

(1), smoke more each day, and are less likely to have made previous attempts to stop smoking

(19) . From a methodological perspective, researchers seeking a higher degree of certainty in the assessment of current smoking abstinence may also require lower carbon monoxide thresholds (e.g., <3 ppm)

(32) .

Arguably, there was a more marked (treatment) dose-response relationship evident in the smoking reduction findings (

Table 1 ). Approximately one-half (41.4% to 57.1%) of the participants who completed the intervention reduced their smoking by at least 50% relative to baseline, compared with less than one-fifth of the comparison group (16.6% to 18.5%). This also extended to those who completed five to seven sessions (at least at 3 months). Given that reducing smoking does not appear to undermine future cessation efforts and may increase motivation

(34), this is a potentially important finding. In a recent review of published nicotine replacement therapy studies (primarily involving smokers not trying to quit), Hughes and Carpenter

(16) reported that 12% to 35% of participants receiving the active treatment reduced their daily cigarette consumption by 50% or greater (including abstainers), compared with 3% to 22% among participants in the control condition. The corresponding 12-month data from this study (31.3% versus 17.9%) are generally consistent with these findings, attesting to the value of targeting reduction, not just abstinence.

The high numbers of cigarettes smoked and levels of nicotine dependence reported in this study

(19) highlights the need for earlier smoking interventions among young people with mental health problems before they become heavy smokers. Current practice guidelines for psychiatrists recommend nicotine replacement therapy use even in early cessation attempts among individuals with psychiatric disorders, as they appear to have more withdrawal symptoms when they stop smoking

(35) . In our study, nicotine replacement therapy commencement was associated with a net reduction of five to eight cigarettes per day, suggesting that higher doses or a longer duration of nicotine replacement therapy use may be necessary to obtain additional benefits. More generally, we should further explore the delivery and uptake of smoking interventions in primary care settings as well as any potential barriers

(36) . There is also an urgent need for further development of more efficacious interventions among smokers with severe mental illnesses who do not respond to interventions such as those evaluated in this study. Pharmacological approaches giving consideration to bupropion (e.g.,

13 ) and Rimonabant, a cannabinoid receptor-1 antagonist

(37), or different combinations of nicotine replacement therapy and motivational interviewing/cognitive behavior therapy interventions are worthy of further investigation. Although other studies have reported benefits of atypical versus typical antipsychotic medication on smoking (e.g.,

10 ), our study did not find a significant benefit, and future studies should address this issue. It is also worth considering specific interventions for those starting on a regimen of clozapine, since this is known to decrease cravings

(38) .

Further study is needed to evaluate long-term nicotine replacement therapy use or extended cognitive behavior therapy interventions, allowing for resumption of treatment following relapse. It has also been suggested that smokers who reduce the number of cigarettes smoked should be informed that they should stop smoking but, if unable to do so in the short-term, that reducing smoking can be helpful in increasing their likelihood of quitting

(11) . Hughes

(34) and McChargue and colleagues

(15) have suggested that reduction-focused smoking interventions among smokers with schizophrenia who do not wish to abstain from cigarettes should be evaluated, which also takes into account medication impacts and changes. The finding that individuals who continue smoking reported a significant decrease in motivation to stop smoking (

Table 2 ) is not at odds with these recommendations by Hughes and McChargue et al. and probably reflects relatively high levels of motivation at the point of recruitment, rather than negative expectations associated with ongoing study participation. There are also important financial and health benefits of smoking reduction among individuals with severe mental illnesses

(34) . Another important finding was that there was a significant improvement for the study groups as a whole on several mental health measures and no worsening of psychotic symptoms over time

Table 3 ), which is consistent with other studies (e.g.,

9,

10) . Thus, the evidence suggests that participation in a smoking cessation study is not associated with the worsening of symptoms.

Our study is currently the largest randomized controlled trial of a smoking intervention among individuals with a psychotic disorder. Since there was no control for therapy time, the possibility exists that the superior outcomes for the smoking intervention participants were because of additional therapist attention and support rather than the specific motivational interviewing/cognitive behavior therapy and nicotine replacement therapy intervention. However, this seems unlikely given the levels of dependence in this study and the evidence supporting the efficacy of combined nicotine replacement therapy and motivational interviewing/cognitive behavior therapy among nonpsychiatric populations

(14,

16) . Given the ubiquitous nature of smoking among people with a psychotic disorder, the heavy costs of smoking among this group and the modest but encouraging findings, further randomized controlled trials examining more comprehensive interventions are probably required as well as assessments of the long-term outcomes of smoking cessation and reduction interventions.